Chapter 2 Endoscopic Therapy of Endobronchial Typical Carcinoid

Case Description

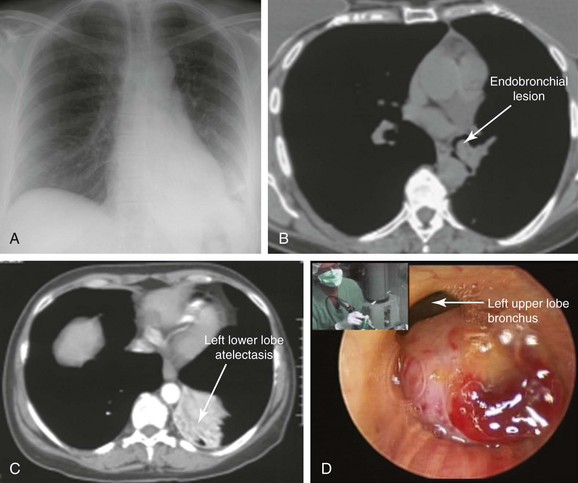

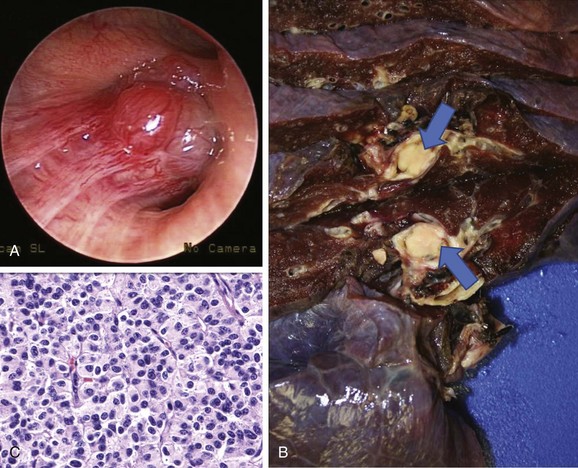

A 47-year-old woman was hospitalized at an outside institution for hemoptysis and left lower lobe pneumonia. She had a history of wheezing for several months, which was unresponsive to bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids. Spirometry was normal. Three weeks before admission, she developed cough and fever. When she developed hemoptysis (half a cup of bright red blood within several hours), she presented to the emergency department. Vital signs showed a temperature of 38.5° C, heart rate of 120 bpm, respiratory rate of 28/min, and blood pressure of 150/75. She had no pain. Wheezing was noted on auscultation of the left hemithorax, and the patient had diminished air entry at the left base. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests were normal except for a white blood cell count of 24,000/mm3. Chest radiography showed left lower lobe opacification (Figure 2-1, A). Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed left lower lobe atelectasis and a distal left main bronchial mass completely obstructing the left lower lobe bronchus and partially obstructing the entrance to the left upper lobe (see Figure 2-1, B). The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics for pneumonia. Flexible bronchoscopy showed an exophytic endoluminal hypervascular distal left main bronchial lesion. Endobronchial biopsies revealed typical carcinoid.*

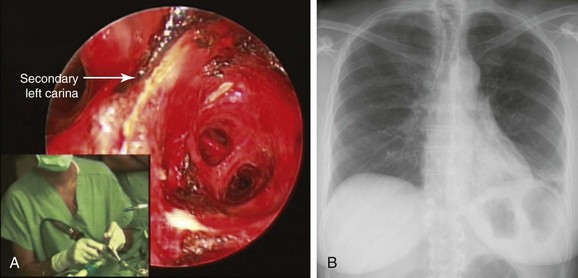

After bronchoscopy, hemoptysis increased, prompting transfer to our institution for palliation and bronchoscopic resection of the endobronchial tumor. Rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia confirmed the flexible bronchoscopic findings (see Figure 2-1). Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd : YAG) laser–assisted resection was performed to restore airway patency (Figure 2-2).

Discussion Points

1. Describe two strategies to decrease the risk of bleeding from bronchoscopic biopsy of this tumor.

2. Discuss the role of imaging studies in diagnosis and staging of carcinoid tumors.

3. List three open surgical treatment alternatives for endobronchial carcinoid.

4. Describe how tumor histology and morphology affect treatment decisions for carcinoid tumors.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

Symptoms in patients with bronchial carcinoid depend on the tumor size, site, and growth pattern. For instance, a small peripheral carcinoid may be an incidental finding, and a large central tumor may result in symptoms similar to those found in our patient: cough, hemoptysis (due to its hypervascularity), and obstructive pneumonia. Some patients may also have shortness of breath.1 The diagnosis is often delayed, and patients may receive several courses of antibiotics, bronchodilators, or inhaled corticosteroids to treat recurrent pneumonia or suspected asthma. In one study, 14% of patients had been treated for asthma for up to 3 years before the tumor was discovered.2 The wheezing noted in our patient was localized to the left hemithorax, reflecting focal airway obstruction, not bronchoconstriction. In fact, diffuse wheezing is rare in patients with carcinoids, regardless of tumor location, because only 1% to 5% of patients exhibit hormone-related symptoms such as carcinoid syndrome.† In part, this reflects the low incidence of hepatic metastases—2% and 5%, respectively—for typical and atypical carcinoids.2,3 In the setting of liver metastasis, however, more than 80% of patients have symptoms of carcinoid syndrome.1 Bronchial and other extraintestinal carcinoids, whose bioactive products are not immediately cleared by the liver, may cause the syndrome in the absence of liver metastasis because of their direct access to the systemic circulation. However, bronchial carcinoids have low serotonin content because they often lack aromatic amino acid decarboxylase and cannot produce serotonin and its metabolites; they only occasionally secrete bioactive amines. Elevated plasma or urinary secretory product levels such as 5′-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5′-HIAA) thus are rarely detected. Elevation of plasma chromogranin A* is a relatively sensitive (≈75%) marker of bronchopulmonary carcinoids, but elevated levels are also seen in approximately 60% of patients with small cell carcinoma, and false-positive elevations can occur in renal impairment, in atrophic gastritis, and during proton pump inhibitor therapy.4 Measurement of its levels is considered useful only in following disease activity in the setting of advanced or metastatic carcinoid.5 No such serologic or urinary testing was performed in our patient before bronchoscopic intervention was provided.

With regard to radiographic studies, when the tumor is centrally located, as in our patient, bronchial obstruction may occur and atelectasis is noted (see Figure 2-1, C). Compared with chest x-ray, CT provides better resolution of tumor extent and location, as well as the presence or absence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy. High-resolution CT allows characterization of centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal, exclusively extraluminal, or, more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components (the “iceberg” lesion). In the setting of post obstructive pneumonia, a clear distinction between intraluminal and extraluminal extension can be properly made only after post obstructive debris and atelectasis have been removed.6 Tumor morphology impacts management because bronchoscopic treatments alone are considered by some investigators to be acceptable therapeutic alternatives for purely intraluminal typical carcinoids.6 Chest CT scan should be performed as part of nodal staging for carcinoid tumors. Atypical carcinoids have a higher recurrence rate and present more often with hilar or mediastinal nodal metastases (20% to 60% vs. 4% to 27%), when compared with typical carcinoids.1 This patient had no evidence of mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy on CT scan; because atelectasis and pneumonia were present, it was unclear whether the tumor had an extraluminal component (e.g., mixed obstruction, iceberg lesion).

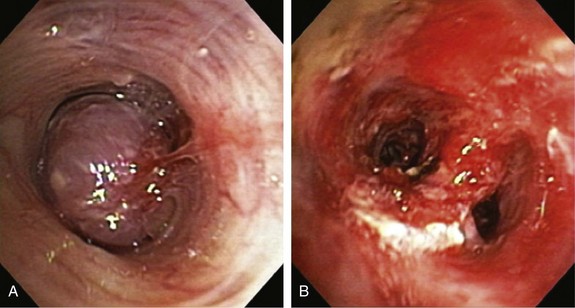

The bronchoscopic appearance of this patient’s carcinoid is classic: a pink to red vascular mass attached to the bronchus by a broad base. In one study, 41% of patients presented with evidence of bronchial obstruction.3 These lesions occasionally can create a ball-valve effect (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video I.2.1![]() ). The hypervascular pattern has raised concern for bleeding following bronchoscopic biopsy. Some authors report bleeding in a quarter to two thirds of their patients, and some advise against biopsy when carcinoid is suspected.7–9 In a review of 587 biopsies by flexible and rigid bronchoscopy, significant hemorrhage was seen in 15 (2.6%) patients, but 11 (1.9%) of these patients did not require transfusion or emergency surgery. In four patients (0.7%), emergency thoracotomy was necessary to address the problem of massive uncontrollable hemorrhage.10 Other authors showed that biopsy is safe, significantly increases the diagnostic yield, and is not associated with significant hemorrhage.3,11 It is wise to have electrocautery, argon plasma coagulation, or a laser readily available to control spontaneous or post biopsy hemorrhage if necessary (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video I.2.2

). The hypervascular pattern has raised concern for bleeding following bronchoscopic biopsy. Some authors report bleeding in a quarter to two thirds of their patients, and some advise against biopsy when carcinoid is suspected.7–9 In a review of 587 biopsies by flexible and rigid bronchoscopy, significant hemorrhage was seen in 15 (2.6%) patients, but 11 (1.9%) of these patients did not require transfusion or emergency surgery. In four patients (0.7%), emergency thoracotomy was necessary to address the problem of massive uncontrollable hemorrhage.10 Other authors showed that biopsy is safe, significantly increases the diagnostic yield, and is not associated with significant hemorrhage.3,11 It is wise to have electrocautery, argon plasma coagulation, or a laser readily available to control spontaneous or post biopsy hemorrhage if necessary (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video I.2.2![]() ).

).

Comorbidities

This patient had no signs or symptoms suggesting hormone-related disorders caused by carcinoid, such as Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, or typical or atypical carcinoid syndrome.*

Patient Preferences and Expectations

The patient had expressed fears of having lung cancer. She wanted clarification in terms of her diagnosis, prognosis, and follow-up after treatment. It was explained to her that bronchial carcinoid tumors are rare lung malignancies that rarely spread outside the chest.*12,13 We were aware of data showing that the incidence of distant metastases at diagnosis for bronchopulmonary carcinoids is 5.5%14; that overall, 27.5% of bronchopulmonary carcinoids exhibit invasive growth or metastatic spread; and that the overall 5-year survival rate is 73.5%. Therefore we did not use the term benign tumor in our conversation with the patient.12 Typical and atypical carcinoids, however, have different biologic behaviors and prognoses, causing them to be considered and reported as different tumors.2 Typical carcinoids, as seen in this patient, usually have a good prognosis, with 5 year survival of 87% to 89%. Distant metastases from typical carcinoids may occur in approximately 10% of patients, even many years after radical resection of the primary tumor. Prolonged 10 year follow-up is therefore recommended. Atypical carcinoids are associated with 5 year survival of 44% to 78%.1

Procedural Strategies

Indications

1. To palliate central airway obstruction in patients who are poor surgical candidates (Figure 2-3).15 Our patient, although considered operable (normal spirometry and no comorbidities), was not a good candidate for open surgery at the time of admission, given her ongoing sepsis from post obstructive pneumonia.

2. To guide open surgical procedures after laser bronchoscopic removal of an obstructing lesion.16 Investigators report that lung-preserving resections are facilitated by preoperative laser treatment in 10% to 12% of patients with central obstructing carcinoids. Treatment of airway obstruction before surgery allows the operator to estimate the extent of bronchoplastic surgery.16,17

3. As a reasonable alternative to immediate surgical resection in patients who present with an exophytic intraluminal tumor, good visualization of the distal tumor margin, and no evidence of bronchial wall involvement or suspicious lymphadenopathy by high-resolution CT. Close post-treatment follow-up is an integral component of such treatment.6

Expected Results

Bronchoscopic resection alone may provide prolonged recurrence-free survival for highly selected patients with a purely exophytic endoluminal bronchial carcinoid.6,18–21 These patients present with a polypoid (exophytic) intraluminal tumor, good visualization of the distal tumor margin (usually less than 2 cm in extent), and no evidence of bronchial wall involvement or suspicious lymphadenopathy by high-resolution CT. In the largest series of 72 patients treated with this approach (57 typical and 15 atypical carcinoids), initial bronchoscopic management resulted in complete tumor eradication in 33 patients (46%). Surgery was required in 37 patients (including 11 of the 15 with atypical carcinoids)—2 for delayed recurrence at 9 and 10 years. At a median follow-up of 65 months, 66 patients (92%) remained alive, and only 1 of the deaths was tumor related.6

Team Experience

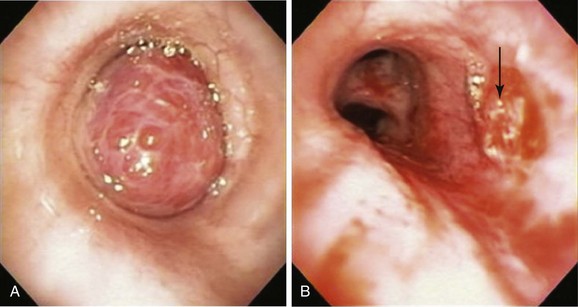

Rigid bronchoscopy with Nd : YAG laser resection is frequently performed in our referral center by a team of doctors and nurses experienced in managing critical central airway obstruction and hemoptysis. The goal of the operating team when this type of laser is used should be to remove unwanted tissue (tumor) with adequate hemostasis and minimum destruction of adjacent healthy tissue. Accurate removal of diseased tissue depends on the surgeon’s ability to visualize tissues and feel and control the shape and size of target tissues in three dimensions. Thus experience is important because complete and clear visualization of the treated area, ensuring hemostasis and minimization of adjacent laser-induced thermal injury, requires skillful operation of the rigid bronchoscope and knowledge of laser physics and laser-tissue interaction. For example, in a patient with mid-left mainstem bronchial carcinoid (Figure 2-4), the goal is precise removal of the lesion with minimal thermal trauma to the normal adjacent mucosa. Resection may be achieved in ways other than vaporization or widespread coagulation of blood vessels. Power density should be employed in ways that avoid damaging surrounding tissues to minimize interference, with consideration for future bronchoplastic procedures. If the tumor is completely removed, some investigators have suggested applying low-power density laser energy to residual bronchial surfaces to ablate and presumably kill residual tumor cells. Deep mucosal biopsies are warranted after a complete resection to ascertain the absence of disease.

Risk-Benefit Analysis

Open surgical resection is the preferred treatment approach for patients whose overall medical condition and pulmonary reserve will tolerate it. For patients whose condition does not permit complete resection, and for exceptional cases in which the lesion is entirely intraluminal, bronchoscopic resection may be an alternative.6 Our patient had post obstructive pneumonia, so we opted for initial bronchoscopic treatment to restore airway patency to the left lower lobe.

Therapeutic Alternatives

1. Surgical resection with complete mediastinal lymph node dissection is, in general, considered the treatment of choice for carcinoid tumor because it offers a real chance of cure. The goal is en bloc resection of the entire neoplasm (Figure 2-5) with preservation of functional pulmonary parenchyma if possible. Attempts to preserve lung parenchyma through the use of bronchoplastic techniques (e.g., sleeve, wedge, flap resection) to avoid lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy are justified and safe.22–24 Parenchyma-sparing operations based on bronchoplastic or sleeve resection do not alter the oncologic result and lead to a better quality of life.25 These procedures are possible only in the absence of “iceberg” lesions (in which the tumor appears entirely intraluminal bronchoscopically but has a significant extraluminal component that is evident with high-resolution computed tomography [HRCT]). The following surgical principles are recommended for bronchial carcinoids:

2. Bronchoscopic treatment with argon plasma coagulation has been reported for recurrent typical bronchial carcinoids.28

3. Bronchoscopic treatment with electrocautery in one prospective study completely eradicated tumor in 14 of 19 patients with intraluminal typical bronchial carcinoid (complete response rate, 73%) after a median follow-up of 29 months. Most of these patients were treated with electrocautery, but it seems that there is no difference between this and Nd : YAG laser with regard to tumor control.18 In a small study including 28 patients with intraluminal carcinoid, followed for a median duration of 8.8 years, five bronchoscopic resections on average were required to achieve complete removal. One and 10 year survival rates were 89% (range, 84% to 93%) and 84% (range, 77% to 91%), respectively. In this study, endoluminal tumor was removed piecemeal with biopsy forceps. Electrocautery was rarely required to control hemorrhage.29

4. Bronchoscopic cryotherapy was found to be successful and safe in a small series of 18 isolated endoluminal typical bronchial tumors.30

5. Definitive radiation therapy can provide palliation of a locally unresectable primary carcinoid.31,32

Cost-Effectiveness

No studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of bronchoscopic resection versus open surgical intervention for carcinoid tumor. Bronchoscopic interventions are cheaper and probably safer than open surgical resections. This may not be the case if, during the follow-up period, surgery was eventually needed in approximately 50% of patients who underwent bronchoscopic resection, as shown in one large series.6 Even though most surgeries were needed for atypical carcinoids, primary surgical resection is recommended by most authorities for operable patients, regardless of histology.

Techniques and Results

Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

Biopsy or manipulation of an actively secreting bronchial carcinoid can rarely induce acute carcinoid syndrome and cardiac arrest because of massive systemic release of bioactive mediators.33,34 When this happens, patients acutely develop flushing, diarrhea, and bronchoconstriction, which can include acidosis, severe hypertension or hypotension, tachycardia, or myocardial infarction. Although not routinely used or recommended, somatostatin analog (octreotide) can be used perioperatively to prevent carcinoid crisis at the time of resection. Octreotide should be readily available during any surgical procedure in patients with carcinoids. Preoperative administration of octreotide (300 micrograms subcutaneously) can reduce the incidence of carcinoid crisis and is done routinely for carcinoid surgery, except with bronchial carcinoids, which only rarely secrete bioactive amines.35 During a carcinoid crisis, blood pressure should be supported by infusion of plasma, and octreotide (300 micrograms IV) given immediately. A continuous IV drip of octreotide (50 to 150 micrograms per hour) may be needed.

Results and Procedure-Related Complications

After induction of general anesthesia with propofol and ramifentanil, the patient was intubated with an 11 mm Efer-Dumon rigid ventilating bronchoscope. Complete obstruction of the left lower lobe bronchus and partial obstruction of the left upper lobe bronchus were noted (see Figure 2-1, B). There was no visibility of the distal airways in the left lower lobe, and it appeared that the tumor was involving the secondary left carina. The tumor was at least 2 cm long and was extending into the superior segment of the left lower lobe bronchus. Nd : YAG laser resection was initiated using 30 watt power, 1 second pulses for a total of 9519 joules. Parts of the tumor were coagulated, after which forceps and the bevel edge of the rigid bronchoscope were used to remove large pieces of tumor. Saline lavage was performed to remove large amounts of pus. Eventually, all bronchial segments of the lower lobe could be visualized (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video I.2.3![]() ). The patient was then extubated and transferred to the postanesthesia care unit, where no complications occurred.

). The patient was then extubated and transferred to the postanesthesia care unit, where no complications occurred.

Long-Term Management

Referral

Bronchoscopic resection is not considered standard curative treatment by many clinicians because of concerns about residual tumor within or beyond the endobronchial lumen. Because of the slow-growing nature of carcinoid tumors, recurrence may take years. Until more data become available, bronchoscopic treatment is best reserved for carefully selected elderly or debilitated patients, patients who refuse open surgery, and those whose symptoms (hemoptysis, pneumonia, or severe shortness of breath) require prompt bronchoscopic control. Our patient had a tumor with a long (>2 cm) base of implantation that extended into the segmental airways. In addition, the airway wall and the secondary left carina were involved. These findings made her a poor candidate for bronchoscopic treatment alone,18 or for subsequent bronchoplastic interventions. Because it was believed that she was a candidate for conventional lung resection, thoracic surgery consultation was requested.

Follow-up Tests and Procedures

Some experts do not perform preoperative staging studies such as somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (octreoscan) or hepatic imaging unless there is clinical suspicion for metastatic disease. Others, however, include chest and upper abdomen CT, bronchoscopy, and the octreoscan in their routine preoperative evaluation.17 The optimal posttreatment surveillance strategy has not been defined, and no consensus has been reached on what tests should be ordered. Some authorities perform history and physical examination and chest CT annually for patients with resected typical carcinoid, and every 6 months for resected atypical carcinoids for the first 2 years, then annually. Others perform chest CT every 6 months, regardless of histology. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy could be performed in the follow-up of patients with bronchial carcinoid if there is suspicion for metastatic disease. Similarly, measurement of serum levels of chromogranin A (CGA) can be useful in following disease activity in the setting of advanced or metastatic disease.

Despite their low malignant potential, long-term follow-up of patients with typical bronchial carcinoids is warranted because local or distant disease recurrence may occur many years after initial treatment. In one large study, follow-up evaluation ranged from 6 months to 36 years (median, 121 months), during which 8% of patients had recurrences diagnosed, most commonly in the liver (55%), followed by lung (25%), bone (20%), adrenal gland (10%), pericardium (10%), and mediastinal lymph nodes (10%). No bronchial recurrences were seen. Recurrent cancer developed preferentially in atypical carcinoids (17.9%, vs. 3.4% in typical carcinoids; P = .0001) and in patients with positive nodes.17

In cases of sole bronchoscopic resection, one strategy is to perform HRCT and flexible bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasonography and tissue biopsy within 6 weeks after endobronchial resection. If the patient is operable, a referral for surgery is warranted if residual disease is evident. If no residual disease is present, repeat evaluation is performed every 6 months for 2 years, and annually thereafter.6

Quality Improvement

We referred this patient to surgery, but we were not sure if there was a role for adjuvant therapy after complete resection of a bronchial carcinoid. No prospective trials have directly addressed the benefit of adjuvant therapy for patients with typical or atypical bronchial carcinoids. Because of their favorable long-term outcomes, even in the presence of mediastinal nodal metastases, most experts agree that adjuvant therapy is not indicated for completely resected, typical bronchial carcinoids.17,36 Despite lack of data and uncertainty as to benefit, guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend chemotherapy and radiation therapy for resected stage II or III atypical carcinoids, but not for typical carcinoids.37

Discussion Points

1. Describe two strategies to decrease the risk of bleeding from bronchoscopic biopsy of this tumor.

2. Discuss the role of imaging studies in diagnosis and staging of carcinoid tumors.

3. List three open surgical treatment alternatives for endobronchial carcinoid.

4. Describe how tumor histology and morphology affect treatment decisions for carcinoid tumors.

Expert Commentary

Bronchial carcinoids are rare, well-differentiated neuroendocrine malignant tumors that account for 1% to 2% of all lung neoplasms.44 As was discussed in the case, typical carcinoids have an excellent long-term prognosis, with 5 year survival ranging from 87% to 97%. Patients with atypical carcinoid, on the other hand, are at greater risk of developing metastases, and 5 year survival ranges from 56% to 77%.

1. Role and reliability of imaging techniques for diagnosis, staging, and follow-up

2. Role, safety, and efficacy of bronchoscopic procedures in diagnosis and treatment

Carcinoid tumors express in high percentage one or more somatostatin receptors; therefore the use of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, with radiolabeled somatostatin analog (111In-octreotide), has become routine in most centers reporting this disease. The sensitivity of Octreoscan is greater than 90%. Its use has been suggested in the diagnosis of primary carcinoids and in the detection of early recurrences, even in asymptomatic patients.45 Octreoscans suffer from low spatial resolution and are able to detect only subtype 2 somatostatin receptor. 18F-FDG PET/CT has limited sensitivity for carcinoids because of low uptake of the marker. Recent progress is represented by 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT, which seems to have high sensitivity for primary tumors and for secondary localizations, with better imaging resolution.46 An additional indication for using these imaging techniques is to enhance the selection of ideal candidates for radiometabolic or somatostatin receptor–targeted anticancer therapy.47

Bronchoscopy is also important as part of a management strategy. Careful preoperative bronchoscopic assessment is important in planning best surgical treatment and in determining the feasibility of a bronchoplastic procedure.48 When major bronchi are obstructed, endoscopic debulking allows the physician to examine the airways beyond the tumor to evaluate its base of implantation and eventually to treat the airway obstruction. Endobronchial laser treatment (necessary in 34.3% of cases in my experience) has significantly increased the frequency with which parenchymal-sparing surgeries can be performed. Similar to the opinion expressed regarding the patient presented, I do not consider laser therapy curative. Usually, endobronchial carcinoids tend to spread extraluminally, and a correct approach should, in my opinion, consist of surgical removal. Moreover, the potential for lymph node involvement (5% to 20% in typical carcinoids), especially micrometastases not revealed by conventional imaging techniques, should require a complete systematic lymphadenectomy.

Some authors have proposed endobronchial laser therapy as definitive treatment for central typical carcinoids.6,21,29 At the moment, very few studies are available, and conflicting results (recurrence rate, 2% to 5%) have been reported. No randomized studies have compared open and endobronchial approaches. Unfortunately, laser treatment rarely allows a radical resection because locally, the base of implantation is often large and deep, and the visible part in the bronchial tree can be only the tip of an iceberg. Radical local endoscopic treatment may be attempted in a highly select population with typical carcinoid tumors that are entirely endobronchial, forming a polypoid lesion with a small (less than 1 cm) base of implantation, a small dimension (probably less than 3 to 4 cm2), no extraluminal growth, and no lymph node involvement noted by diagnostic imaging techniques. The procedure should be carried out by very experienced operators who are able to correctly use a laser, and who have access to high-resolution CT scanning and endobronchial ultrasound, which may prove helpful in monitoring biopsies to ensure complete bronchoscopic resection or in evaluating local recurrence. Surveillance should be prolonged because recurrence can occur even many years after the initial procedure, or spread to lymph nodes may be noted.

Surgery represents the treatment of choice for bronchial carcinoid, and parenchymal-sparing resections such as sleeve or bronchoplastic procedures have been suggested for central carcinoid tumors.48 Despite this, a number of surgical aspects are still controversial. In my experience, a significantly increased number of sleeve resections or bronchoplastic procedures for centrally located carcinoids led to a significant reduction in the number of pneumonectomies in previous years. These results were obtained as a result of improvements in surgical techniques, but also because of the popularization of parenchymal-sparing operations based on bronchoplastic or sleeve resections, which do not alter the oncologic result and obviously guarantee a better quality of life. Therefore I think that modern management of central carcinoids should privilege, when possible, sleeve resections, given that oncologic results are good and the rate of local recurrence is low in most experiences.22–26,48–50 The need to avoid pneumonectomy gains greater weight when we consider that central typical carcinoid preferentially affects young people.51

Surgical resection of carcinoid tumors should always be combined with systematic lymph node dissection. The necessity for lymph node dissection is justified by the possibility of lymph node metastases, the incidence of which may range from 6% to 25%.19,52 The prognostic relevance of lymph node involvement has been underlined by several authors17,19,52,53; therefore investigation into lymph node metastases seems an unavoidable prerequisite for establishing prognosis, and eventually for evaluating opportunities for adjuvant therapies. The accuracy of pathologic diagnosis can be enhanced, as demonstrated by Mineo et al., who described the relevance of lymph node micrometastases detected by immunohistochemical techniques.54

1. Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Chan A, et al. Bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer.. 2008;113:5-21.

2. Filosso PL, Rena O, Donati G, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: surgical management and long-term outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2002;123:303-309.

3. Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest.. 2001;119:1647-1651.

4. Seregni E, Ferrari L, Bajetta E, et al. Clinical significance of blood chromogranin A measurement in neuroendocrine tumours. Ann Oncol.. 2001;12(suppl 2):S69-S72.

5. Campana D, Nori F, Piscitelli L, et al. Chromogranin A: is it a useful marker of neuroendocrine tumors? J Clin Oncol.. 2007;25:1967-1973.

6. Brokx HA, Risse EK, Paul MA, et al. Initial bronchoscopic treatment for patients with intraluminal bronchial carcinoids. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2007;133:973-978.

7. Marty-Anè C, Costes V, Pujol J, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the lung: do atypical features require aggressive management? Ann Thorac Surg.. 1995;59:78-83.

8. Todd T, Cooper J, Weisberg D, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: twenty years’ experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 1980;79:32-36.

9. McCoughan BC, Martini N, Bains M. Bronchial carcinoids: review of 124 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 1985;89:8-17.

10. Dusmet ME, McKneally MF. Pulmonary and thymic carcinoid tumors. World J Surg.. 1996;20:189-195.

11. Rea F, Binda R, Spreafico G, et al. Bronchial carcinoids: a review of 60 patients. Ann Thorac Surg.. 1989;47:412-414.

12. Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer.. 2003;97:934-959.

13. Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America. Cancer.. 2008;113:2655-2664.

14. Quaedvlieg PF, Visser O, Lamers CB, et al. Epidemiology and survival in patients with carcinoid disease in The Netherlands: an epidemiological study with 2391 patients. Ann Oncol.. 2001;12:1295-1300.

15. Diaz-Jimenez JP, Canela-Cardona M, Maestre-Alcacer J. Nd:YAG laser photoresection of low-grade malignant tumors of the tracheobronchial tree. Chest.. 1990;97:920-922.

16. Schreurs AJ, Westermann CJ, van den Bosch JM, et al. A twenty-five-year follow-up of ninety-three resected typical carcinoid tumors of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 1992;104:1470-1475.

17. Rea F, Rizzardi G, Zuin A, et al. Outcome and surgical strategy in bronchial carcinoid tumors: single institution experience with 252 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.. 2007;31:186-191.

18. van Boxem TJ, Venmans BJ, van Mourik JC, et al. Bronchoscopic treatment of intraluminal typical carcinoid: a pilot study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 1998;116:402-406.

19. Cardillo G, Sera F, Di Martino M, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: nodal status and long-term survival after resection. Ann Thorac Surg.. 2004;77:1781-1785.

20. Harpole DHJr, Feldman JM, Buchanan S, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: a retrospective analysis of 126 patients. Ann Thorac Surg.. 1992;54:50-54.

21. Van Boxem TJ, Golding RP, Venmans BJ, et al. High-resolution CT in patients with intraluminal typical bronchial carcinoid tumors treated with bronchoscopic therapy. Chest.. 2000;117:125-128.

22. Terzi A, Lonardoni A, Feil B, et al. Bronchoplastic procedures for central carcinoid tumors: clinical experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.. 2004;26:1196-1199.

23. El Jamal M, Nicholson AG, Goldstraw P. The feasibility of conservative resection for carcinoid tumors: is pneumonectomy ever necessary for uncomplicated cases? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.. 2000;18:301-306.

24. Lucchi M, Melfi F, Ribechini A, et al. Sleeve and wedge parenchyma-sparing bronchial resections in low-grade neoplasms of the bronchial airway. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2007;134:373-377.

25. Wilkins EWJr, Grillo HC, Moncure AC, et al. Changing times in surgical management of bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumor. Ann Thorac Surg.. 1984;38:339-344.

26. Cerfolio RJ, Deschamps C, Allen MS, et al. Mainstem bronchial sleeve resection with pulmonary preservation. Ann Thorac Surg.. 1996;61:1458-1462.

27. Martini N, Zaman MB, Bains MS, et al. Treatment and prognosis in bronchial carcinoids involving regional lymph nodes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 1994;107:1-6.

28. Orino K, Kawai H, Ogawa J. Bronchoscopic treatment with argon plasma coagulation for recurrent typical carcinoids: report of a case. Anticancer Res.. 2004;24:4073-4077.

29. Luckraz H, Amer K, Thomas L, et al. Long-term outcome of bronchoscopically resected endobronchial typical carcinoid tumors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2006;132:113-115.

30. Bertoletti L, Elleuch R, Kaczmarek D, et al. Bronchoscopic cryotherapy treatment of isolated endoluminal typical carcinoid tumor. Chest.. 2006;130:1405-1411.

31. Mackley HB, Videtic GM. Primary carcinoid tumors of the lung: a role for radiotherapy. Oncology.. 2006;20:1537-1543.

32. Chakravarthy A, Abrams RA. Radiation therapy in the management of patients with malignant carcinoid tumors. Cancer.. 1995;75:1386-1390.

33. Karmy-Jones R, Vallieres E. Carcinoid crisis after biopsy of a bronchial carcinoid. Ann Thorac Surg.. 1993;56:1403-1405.

34. Mehta AC, Rafanan AL, Bulkley R, et al. Coronary spasm and cardiac arrest from carcinoid crisis during laser bronchoscopy. Chest.. 1999;115:598-600.

35. Kinney MA, Warner ME, Nagorney DM, et al. Perianaesthetic risks and outcomes of abdominal surgery for metastatic carcinoid tumours. Br J Anaesth.. 2001;87:447-452.

36. Morandi U, Casali C, Rossi G. Bronchial typical carcinoid tumors. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2006;18:191-198.

37. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines™). Neuroendocrine tumors, Version 2.2010 www.nccn.org Accessed March 23, 2011

38. Granberg D, Sundin A, Janson ET, et al. Octreoscan in patients with bronchial carcinoid tumours. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;59:793-799.

39. Musi M, Carbone RG, Bertocchi C, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: a study on clinicopathological features and role of octreotide scintigraphy. Lung Cancer.. 1998;22:97-102.

40. Yellin A, Zwas ST, Rozenman J, et al. Experience with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in the management of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Isr Med Assoc J.. 2005;7:712-716.

41. Daniels CE, Lowe VJ, Aubry MC, et al. The utility of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the evaluation of carcinoid tumors presenting as pulmonary nodules. Chest.. 2007;131:255-260.

42. Orlefors H, Sundin A, Garske U, et al. Whole-body (11)C-5-hydroxytryptophan positron emission tomography as a universal imaging technique for neuroendocrine tumors: comparison with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and computed tomography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.. 2005;90:3392-3400.

43. Dromain C, de Baere T, Lumbroso J, et al. Detection of liver metastases from endocrine tumors: a prospective comparison of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol.. 2005;23:70-78.

44. Hage R, Brutel de la Riviere A, Seldenrijk CA, et al. Update in pulmonary carcinoid tumors: a review article. Ann Surg Oncol.. 2003;10:697-704.

45. Gustafsson B, Kidd M, Modlin I. Neuroendorine tumors of the diffuse neuroendocrine system. Curr Opin Oncol.. 2008;20:1-12.

46. Frilling A, Sotiropoulos GC, Radtke A, et al. The impact of 68Ga-DOTATOC positron emission tomography/computed tomography on the multimodal management of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg.. 2010;252:850-856.

47. Sun LC, Coy DH. Somatostatin receptor-targeted anti-cancer therapy. Curr Drug Deliv.. 2011;8:2-10.

48. Rizzardi G, Marulli G, Bortolotti L, et al. Sleeve resections and bronchoplastic procedures in typical central carcinoid tumours. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.. 2008;56:42-45.

49. Massard G, Ducrocq X, Thomas P, et al. Typical carcinoid tumors of the bronchi: an update. J Cardiovasc Surg.. 2002;43:16-21.

50. Tastepe AI, Kurul IC, Demircan S, et al. Long-term survival following bronchotomy for polypoid bronchial carcinoid tumours. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.. 1998;14:575-577.

51. Rizzardi G, Marulli G, Calabrese F, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumours in children: surgical treatment and outcome in a single institution. Eur J Pediatr Surg.. 2009;19:228-231.

52. Thomas CFJr, Tazelaar HD, Jett JR. Typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids: outcome in patients presenting with regional lymph node involvement. Chest.. 2001;119:1143-1150.

53. Garcia-Yuste M, Matilla JM, Alvarez-Gago T, et al. Prognostic factors in neuroendocrine lung tumors: a Spanish Multicenter Study. Spanish Multicenter Study of Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung of the Spanish Society of Pneumonology and Thoracic Surgery (EMETNE-SEPAR). Ann Thorac Surg.. 2000;70:258-263.

54. Mineo TC, Guggino G, Mineo D, et al. Relevance of lymph node micrometastases in radically resected endobronchial carcinoid tumors. Ann Thorac Surg.. 2005;80:428-432.

* World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for typical carcinoid include a tumor with carcinoid morphology and <2 mitoses/2 mm2 (10 high-power fields [HPFs]), lacking necrosis, and tumor 0.5 cm or larger. An atypical carcinoid is defined as a tumor with carcinoid morphology with 2 to 10 mitoses/2 mm2 and/or necrosis (often punctate).

† Carcinoid syndrome is caused by systemic release of vasoactive substances. Acute symptoms include cutaneous flushing, diarrhea, and bronchospasm (10% to 20 % of patients with carcinoid syndrome); long-term sequelae of prolonged elevated hormone levels include venous telangiectasias, right-side predominant valvular heart disease, and fibrosis in the retroperitoneum and other sites.

* Chromogranins (designated as A, B, and C) are proteins that are stored and released with peptides and amines in a variety of neuroendocrine tissues.

* Disorientation, anxiety, tremor, periorbital edema, lacrimation, salivation, hypotension, tachycardia, diarrhea, dyspnea, asthma, and edema.

* Bronchial carcinoids account for approximately 1% to 2% of all pulmonary malignancies in adults and in approximately 20% to 30% of all carcinoid tumors.

* Administration of a radiolabeled form of the somatostatin analog octreotide results in normal uptake of the isotope in the spleen and bladder, and to a lesser extent in the liver.