CHAPTER 10 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Photodynamic therapy was written by Jacques Etienne.

10.2 Indications for diagnostic ERCP

1 Indications

1.2 Biliary

1.3 Pancreatic

Adler DG, Baron TH, Davila RE, et al. ASGE guidelines: the role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:1.

Cohen D, Bacon BR, Berlin JA, et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: ERCP for diagnosis and therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:803.

10.3 Drugs used in ERCP

Introduction

In addition to the usual medications used for sedation (see Ch. 2.3), glucagon and secretin are sometimes use to aid identification of the major or minor papillae or assist cannulation.

10.4 Equipment

Key Points

1 Endoscopes

1.1 Video duodenoscope

Fr stent. As their diameter is slimmer, they are useful where there is altered anatomy (i.e. Billroth I), a stricture, or if an ERCP is being performed in a child or young adult.

Fr stent. As their diameter is slimmer, they are useful where there is altered anatomy (i.e. Billroth I), a stricture, or if an ERCP is being performed in a child or young adult.1.2 Forward viewing endoscope

2 ERCP equipment

2.2 Sphincterotomes

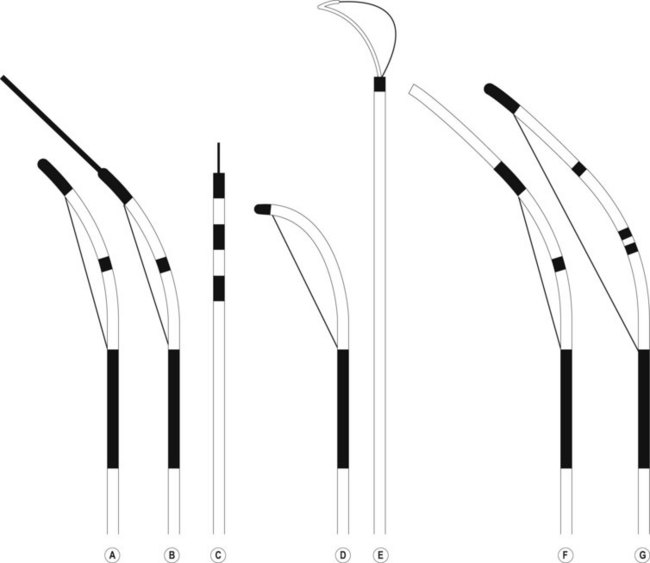

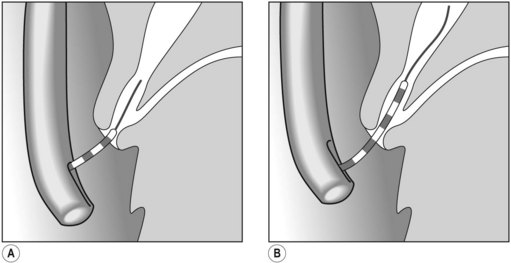

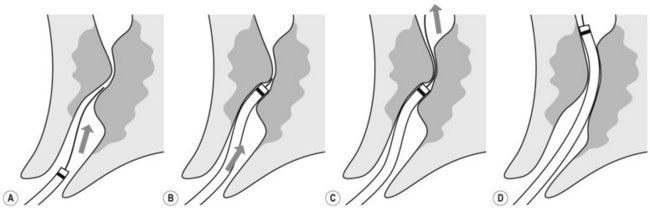

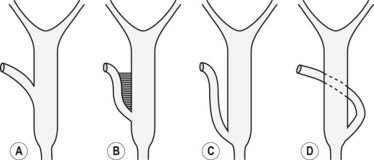

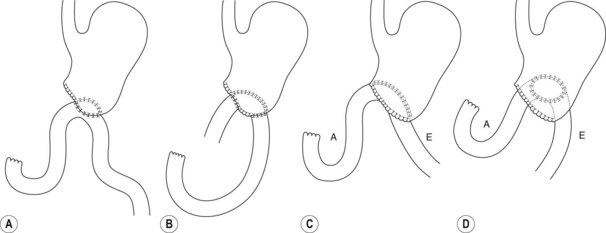

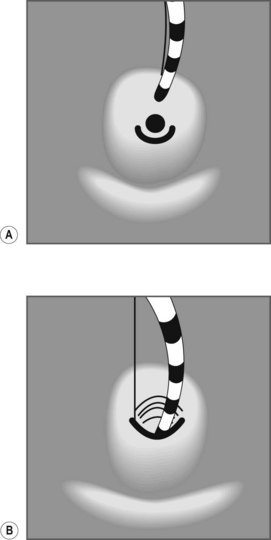

Several different types of sphincterotomes are available. A double-lumen sphincterotome allows either injection of contrast or a guidewire (Fig. 1A). A triple lumen sphincterotome (Fig. 1B) allows injection of contrast without removing the guidewire. A tapered tip (5 mm tip) (Fig. 1D) is sometimes used if the papilla is stenotic or to cannulate the minor papilla. In patients in whom the orientation of the biliary and pancreatic ducts are reversed (i.e. Billroth II), a special sphincterotome is available which is orientated in the opposite direction to the regular sphincterotome (Fig. 1E). Where sphincterotomy fails, a needle-knife sphincterotome with a retractable wire or blade with guidewire option (Fig. 1C) can be used. Sphincterotomes with long cutting wires (Fig. 1G) are no longer used due to an increased risk of bleeding and perforation. The sphincterotome with a long tip nose (Fig. 1F) was used prior to guidewire cannulation, but is rarely used now.

2.4 Brushes

Wire guided brushes are available and are used to obtain tissue from suspicious strictures.

2.7 Wires

2.7.1 Short wire system

They are three components to the short wire system:

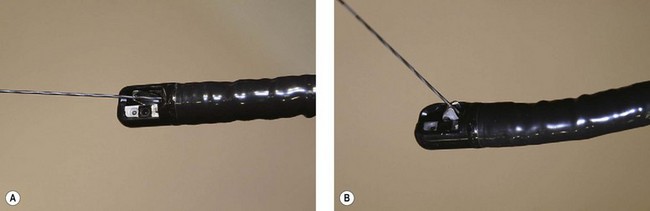

There are currently three short wire systems. The V system (Olympus, Toyko, Japan), contains the ‘V’ locking device. This is an elevator with a V-shaped groove on the elevator, which acts as an internal wire lock (Fig. 2), securing the wire and allowing devices to be removed over the wire without exchanging with an assistant.

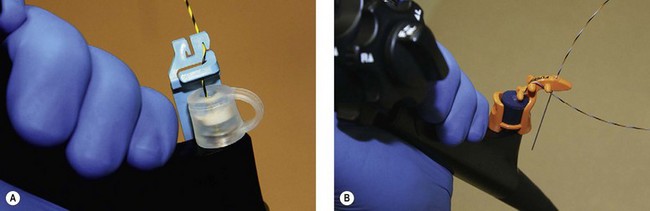

Both the Fusion System (Cook Endoscopy; Winston Salem, NC) and the RX Biliary System (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) consist of short wire systems with external wire locking systems. They both have specially designed biopsy caps, which prevent leaking of air or bile. The Fusion System incorporates a wire lock with port cap (Fig. 3B), while the RX Biliary System has a separate anti-leak biopsy cap, and a wire lock which is attached to the handle of the endoscope and allows fixation of two wires (Fig. 3A). A large variety of compatible devices are available (see Shah et al 2007, for information on available devices) including sphincterotomes and stents.

2.8 Other equipment

A selection of other equipment should be available. This includes:

3 Radiology suite and equipment

3.1 General radiology equipment

10.5 Checklist before starting an ERCP

2 Endoscopist checklist

10.6 Basic ERCP technique

Key Points

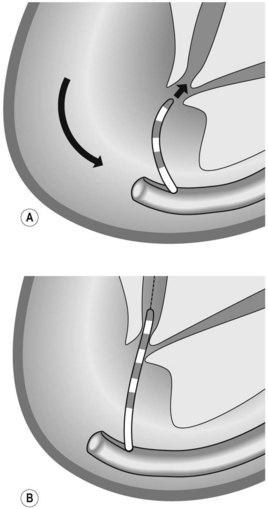

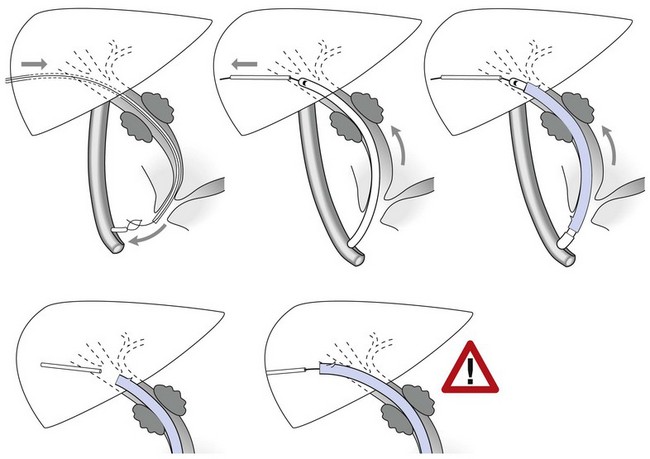

1 Inserting the duodenoscope and positioning over the papilla

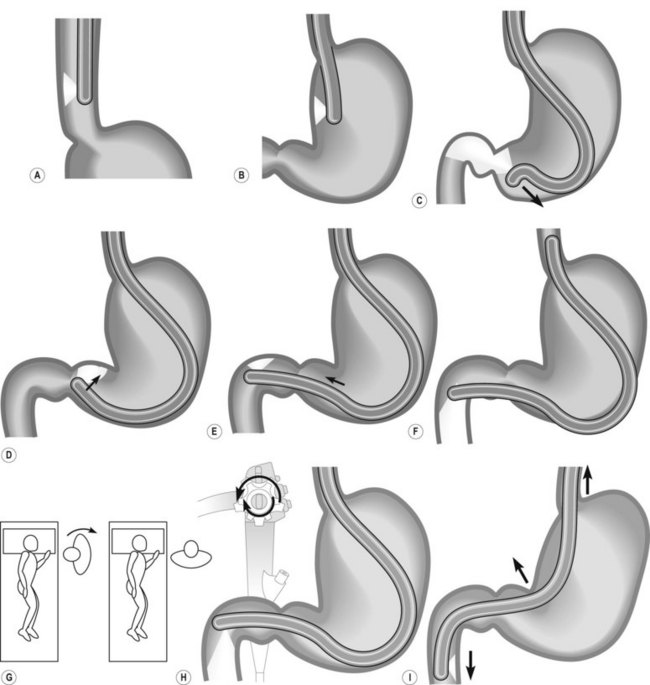

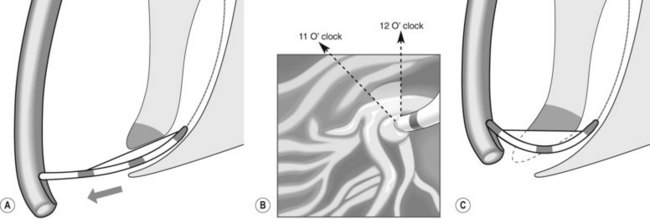

How to intubate and position the duodenoscope in front of the papilla is illustrated in Figure 1. Gently insert the duodenoscope to the upper esophageal sphincter. The esophagus is intubated blindly with gentle forward pressure and slight clockwise rotation. If there is resistance STOP, and change to a forward viewing gastroscope to exclude anything which may cause difficulties with intubation (i.e. Zenker’s diverticulum/stricture). Due to the side-viewing nature of the duodenoscope, a full view of the esophagus is not possible. Once the duodenoscope passes the gastroesophageal junction, make a half turn clockwise and follow the lesser curve to the pylorus. As the duodenoscope is side viewing, the duodenum is entered by placing the pylorus in the ‘setting sun’ position, so that the upper half of the pylorus is visible at the 6 o’clock position. Check that the shaft of the scope is at the 12 o’clock position when intubating the pylorus as this ensures optimum positioning in front of the papilla. The duodenoscope is then inserted into the second part of the duodenum. Two maneuvers are performed in succession: first turn the big wheel anticlockwise and the small wheel clockwise, thus deflecting the tip of the scope up and right, then withdraw the endoscope to 50–70 cm from the incisors to reduce the gastric loop.

1.1 Problems with intubation

Rotate the scope to the right through 90°, by turning from facing the patient to facing the monitor video and be perpendicular to the patient (Fig. 7) patient. This will present the second part of the duodenum.

Rotate the scope to the right through 90°, by turning from facing the patient to facing the monitor video and be perpendicular to the patient (Fig. 7) patient. This will present the second part of the duodenum.2 Locating the papilla

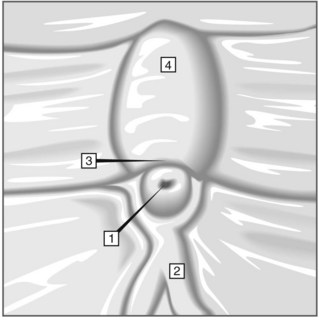

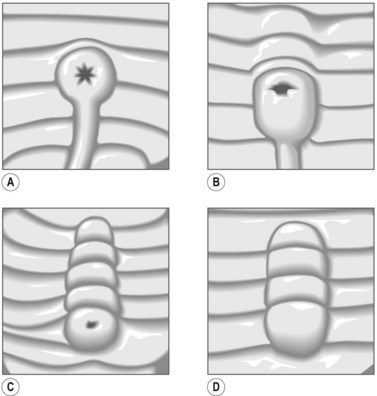

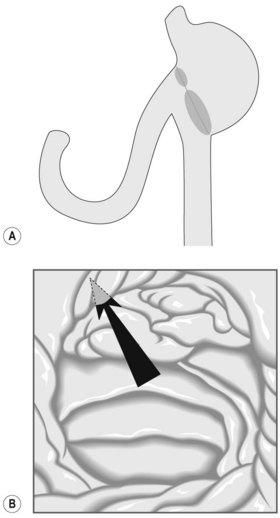

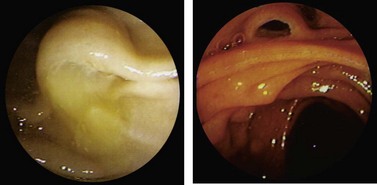

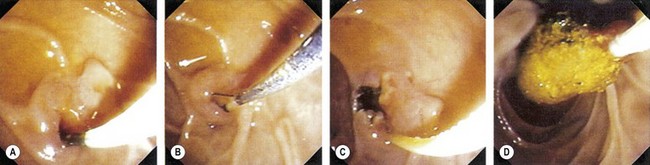

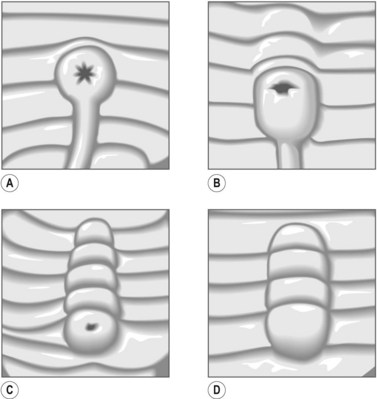

The major papilla should now be in the field of vision. The major papilla consists of a frenulum, a hood, infundibulum, and orifice (Fig. 2). It is often a different color from the rest of the duodenum. The papilla should be inspected for evidence of stone passage (gaping or inflamed orifice), edema or papillary adenoma. The major papilla is then classified depending on its appearance (Fig. 3). This is important when assessing how far a sphincterotomy may be extended and to do a diathermic puncture of biliary infundibulum.

2.1 Problems identifying the major papilla

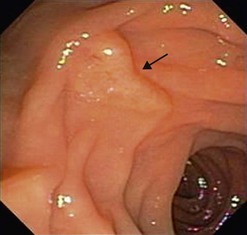

In cases where there is difficulty identifying the major papilla, look for the ‘neck tie’ appearance with a longitudinal fold (Fig. 4) in the second part of the duodenum.

2.2 Locating the minor papilla

The minor papilla is smaller (Fig. 5), and is usually located 2 cm proximal and anterior to the major papilla in the second part of the duodenum. It can be difficult to locate. In these cases consider the following:

3 Cannulating the major papilla

3.1 Cannulating the bile duct and pancreatic duct

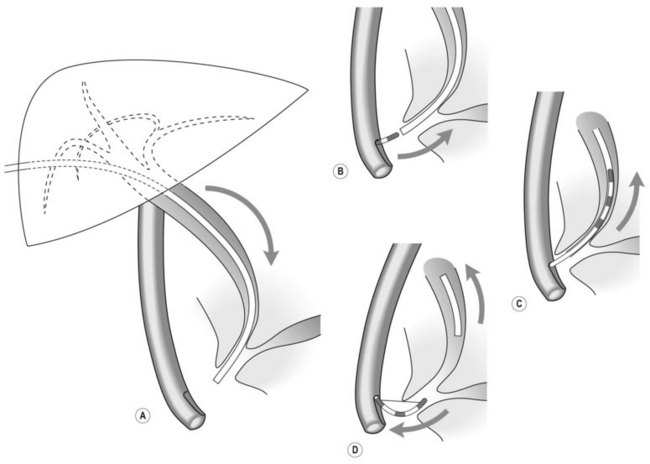

To selectively cannulate the bile duct, the side-viewing duodenoscope should be placed below the major papilla. Place the catheter slightly below the papilla and direct the catheter vertically towards 11–12 o’clock (Fig. 6) in the right upper quadrant. Cannulation of the pancreatic duct requires the duodenoscope to be placed en-face, and slightly to the left of the papilla. The catheter should be placed on the right side of the papilla between 1 and 3 o’clock, with the catheter moving from left to right. If the os is difficult to catheterize, the catheter can initially be introduced a few millimeters, then directed towards the biliary or pancreatic orifice. The catheter is then introduced as far as possible into the chosen duct.

Box 2 Role of a guidewire

![]() Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

How do I know which duct I am in?

The direction of the guidewire can be used to confirm which duct has been cannulated. The wire should advance towards the diaphragm, moving towards 11 o’clock, when the bile duct is cannulated. The guidewire initially moves towards 1 o’clock followed by the 3 o’clock position if the pancreatic duct is cannulated.

The direction of the guidewire can be used to confirm which duct has been cannulated. The wire should advance towards the diaphragm, moving towards 11 o’clock, when the bile duct is cannulated. The guidewire initially moves towards 1 o’clock followed by the 3 o’clock position if the pancreatic duct is cannulated.4 Failure to cannulate the desired duct

Use fluoroscopy to check the position of the endoscope and the direction of the catheter. To cannulate the bile duct, check that the tip of the endoscope is slightly under the papillary orifice, with the catheter pointing towards 11 o’clock (Fig. 7). For the pancreatic duct, the tip of the endoscope should be placed in the same area as the papillary orifice, with the catheter directed towards 1–3 o’clock (Fig. 7).

Use fluoroscopy to check the position of the endoscope and the direction of the catheter. To cannulate the bile duct, check that the tip of the endoscope is slightly under the papillary orifice, with the catheter pointing towards 11 o’clock (Fig. 7). For the pancreatic duct, the tip of the endoscope should be placed in the same area as the papillary orifice, with the catheter directed towards 1–3 o’clock (Fig. 7).5 Cannulating the papilla beside a diverticulum

Diverticulae frequently occur in the second part of the duodenum, especially in elderly individuals. In these cases, look for the papilla at the edges or inside the diverticulum (Fig. 9). Occasionally it is hidden by the duodenal folds, which should be lifted using a catheter. If the papilla cannot be identified, identify the frenulum and hence the papilla. Cannulating a papilla located at the edge, inside or in the middle of a diverticulum is usually possible. The difficulty arises when the papilla is located inside the diverticulum and with the os also facing towards the inside of the diverticulum. In these cases, the following can be tried:

6 Cannulating a stricture

8 ERCP in patients with altered anatomy

8.2 Which endoscope to use?

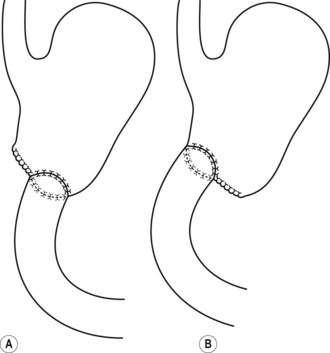

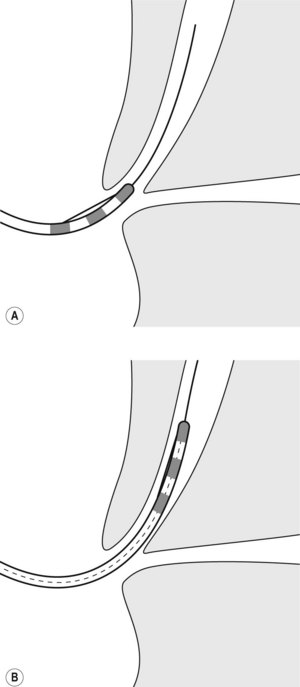

A duodenoscope is usually used where possible, as the presence of the elevator facilitates cannulation. In addition, the side viewing assists location of the ampulla (Fig. 14A). However, it is sometimes not possible to reach the papillary area due to the length of the afferent loop. In these cases, a forward viewing scope should be used. Reaching the ampulla is often successful with a forward viewing scope; however, the ampulla can be more difficult to visualize (Fig. 14B), and the lack of an elevator can make cannulation or exchanging over a guidewire difficult. The choice of forward viewing scope depends on what is available in the unit and the experience of the endoscopist. Options include a pediatric colonoscope, a single or double balloon enteroscope, or an enteroscope with Spirus overtube. Where a forward-viewing endoscope is used, but cannulation has failed, it is possible to leave a wire and then backload this wire onto a duodenoscope.

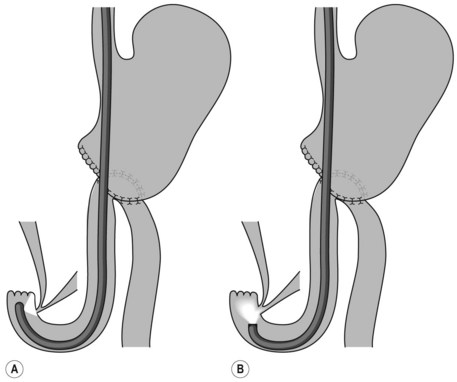

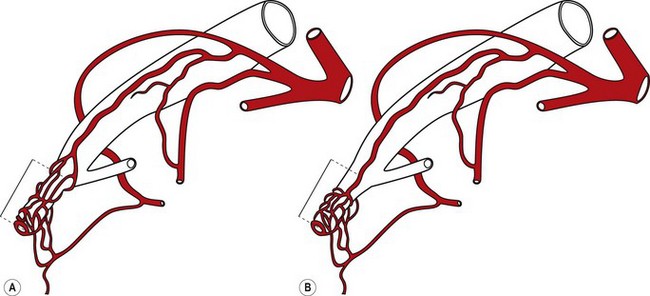

8.5 Choledochoduodenal anastomosis

For patients with a choledochoduodenal anastomosis (Fig. 15A), a forward-viewing endoscope is sometimes required. The anastomosis is usually located on the anterior side of the bulb. If the anastomosis is patent, the endoscope can be introduced into the bile duct. If it is an end-to-side choledochoduodenal anastomosis (Fig. 15B), i.e. if the segment underlying the anastomosis is closed, access to the papilla should be gained using a duodenoscope.

![]() Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Sump syndrome

’Sump syndrome’ is a rare complication of a side-to-side choledochoduodenostomy (Fig. 15A). The common bile duct between the anastomosis and the ampulla of Vater acts as a reservoir in which debris and stones collect. This can result in abdominal pain, cholangitis, biliary obstruction or pancreatitis. ERCP findings include dilated bile or pancreatic duct, and signs of chronic pancreatitis.

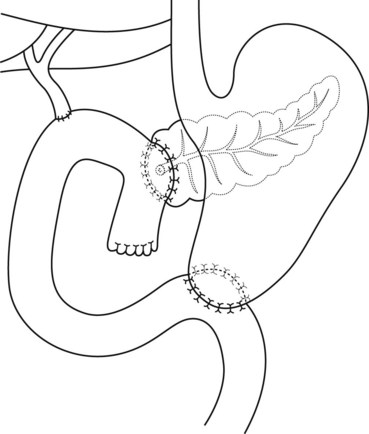

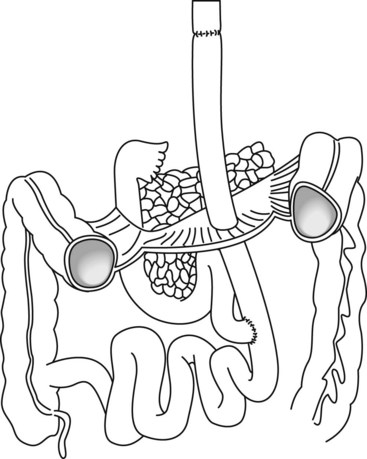

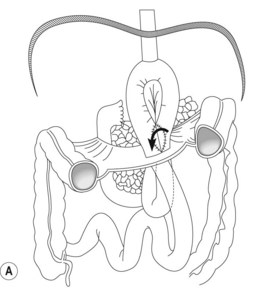

8.6 Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s)

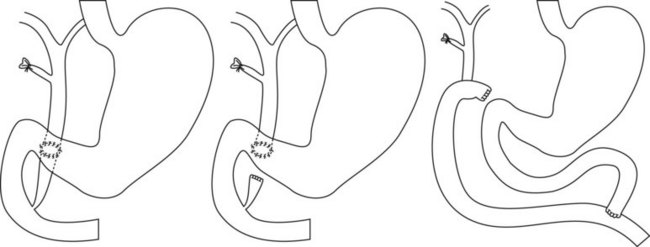

The classic pancreaticoduodenectomy described by Whipple consists of removal of the pancreatic head, duodenum, first 15 cm of the jejunum, common bile duct, and gallbladder, as well as a partial gastrectomy (Fig. 16). There is a side-to-side gastrojejunostomy, often with a long afferent loop and a variety of placements for the pancreatico- and hepatico-jejunostomies. In a pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, the gastric antrum, pylorus, and proximal 3–6 cm of the duodenum are preserved, with an end-to-side pylorojejunostomy. The pancreaticojejunostomy is usually located at the apex of the loop, with the hepatic-jejunotomy about half way down the afferent loop. In these patients, pancreatic and biliary anastomoses can rarely be reached with a duodenoscope and a forward viewing endoscope should be used.

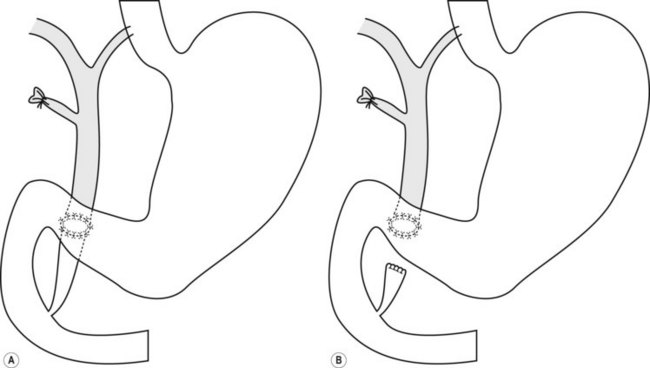

8.7 Gastrojejunal anastomosis (Billroth II)

A Billroth II was often performed in patients with peptic ulcer disease or gastric antral carcinoma and consists of a partial gastrectomy with end-to-side gastrojejunostomy (Fig. 17). The operation may also be known as a Polya and Hoffmeister, depending on how the gastrojejunostomy is performed. A duodenoscope should be used initially. If this is unsuccessful, it can be exchanged for a forward viewing endoscope. There is a native papilla, but the pancreatico-biliary anatomy is reversed as described in the pancreaticoduodenectomy.

8.9 Gastric bypass surgery

Box 5 How to reach the papilla in a patient with an afferent limb

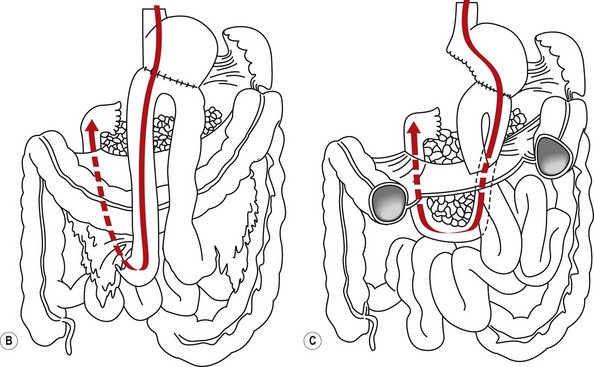

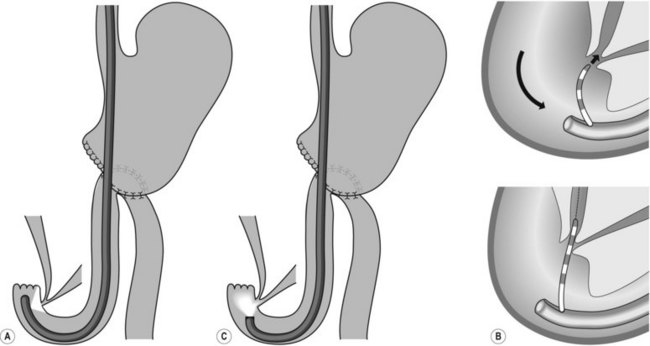

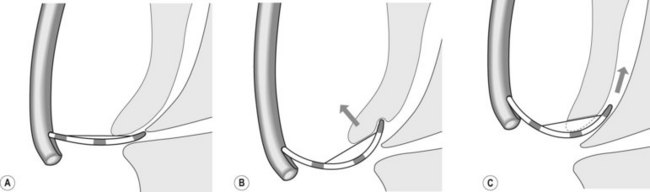

8.10 Cannulating the bile duct and pancreatic duct in patients with Billroth II or Whipple’s procedure

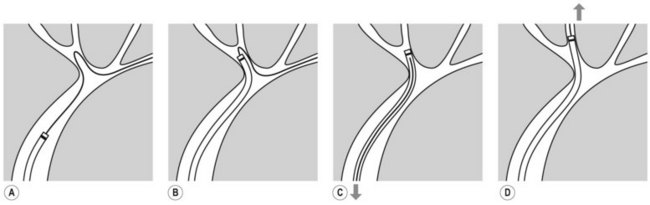

In Billroth II the ampulla will be intact, while in a Whipple’s or other reconstructive surgery there will be a surgical anastomosis (i.e. choledochoenteric anastomosis), and the pancreatic and bile duct anastomoses are usually found separately in the jejunum. The pancreatic duct is often located just proximal to the end of the loop, while the biliary orifice is located proximal to the pancreatic orifice, on the anti-mesenteric wall. As the papilla has been reached retrograde through the afferent loop, the anatomy is reversed by 180° with the biliary orifice found between 5 and 6 o’clock rather than the normal 11 o’clock position (Fig. 18). A straight catheter can be used to cannulate the bile duct or pancreatic duct. It is helpful to maintain an en-face position and exaggerated distance away from the ampulla. A standard cannula is sometimes useful, as a standard sphincterotome may make biliary cannulation difficult in this situation due to its pre-curve. In our experience, guidewire cannulation is particularly useful in these circumstances.

8.11 Rendezvous procedure

Alternative techniques

![]() Clinical tips for patients with a PTC

Clinical tips for patients with a PTC

10.7 Cytology, biopsies, and biochemical analysis

Key Points

4 Biochemical examination of bile and pancreatic juice

10.8 Pancreaticobiliary anatomy

Key Points

1 Normal and variant biliary anatomy

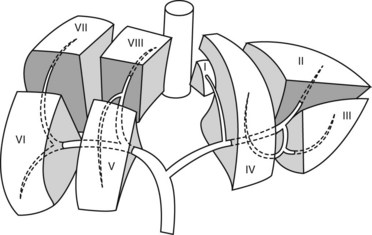

The Couinaud classification gives eight functionally independent segments, numbered I through VIII (Fig. 1). The segments are numbered in a clockwise manner starting with the caudate lobe (segment I). Each segment has its own vascular inflow, outflow, and biliary drainage. In the center of each segment there is a branch of the portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct. In the periphery of each segment, there is vascular outflow through the hepatic veins. The liver is divided by vascular structures. The right hepatic vein divides the right lobe into anterior and posterior segments. The middle hepatic vein divides the liver into right and left lobes, while the left hepatic vein divides the left lobe into medial and lateral parts. The portal vein divides the liver into upper and lower segments.

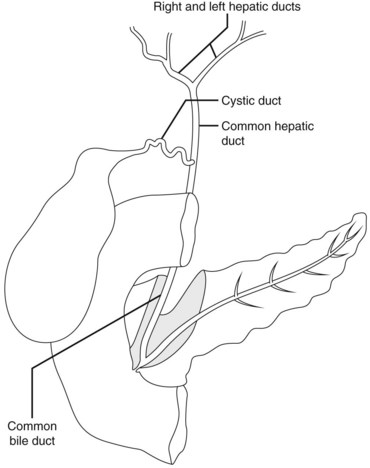

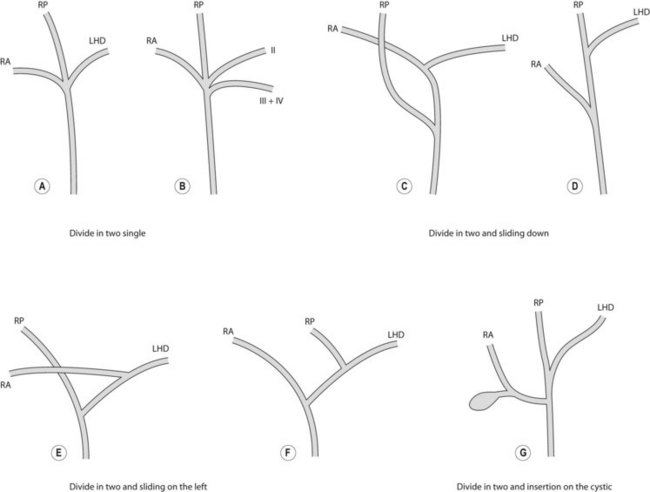

The biliary drainage runs in parallel to the portal venous supply. The right hepatic duct drains the segments of the right liver (V–VIII), with the right posterior duct draining the posterior segment (VI and VII), and the right anterior duct draining the anterior segments (V, VIII). The right posterior duct has an almost horizontal course, while the right anterior duct tends to have a more vertical course. The left hepatic duct is formed from tributaries draining segments II–IV. The common hepatic duct is formed by fusion of the right and left hepatic ducts. The duct draining the caudate lobe (I) usually joins the origin of the right or left hepatic duct. The cyst duct usually joins the common hepatic duct below the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts (Fig. 2).

There are variations of this classic anatomy. The most common variant, which is present in up to 19% of the population, is where the right posterior duct drains into the left hepatic duct before its confluence with the right anterior duct (Fig. 3D). Another common variant, occurring in 12% of individuals, is where the right posterior duct empties into the right aspect of the right anterior duct. Another common variant is where the right anterior, posterior, and left hepatic ducts drain simultaneously into the common hepatic duct (Fig. 3A). In these individuals, the right hepatic duct is virtually non-existent.

The cystic duct termination exhibits a number of variants. A common variation is where there is a low insertion of the cystic duct into the distal third of the common bile duct (9%) (Fig. 4). Another variation is where the cystic duct drains into the left side of the common hepatic duct.

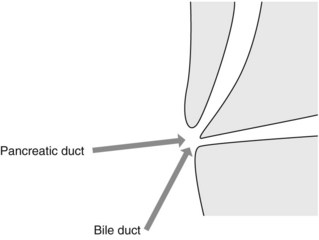

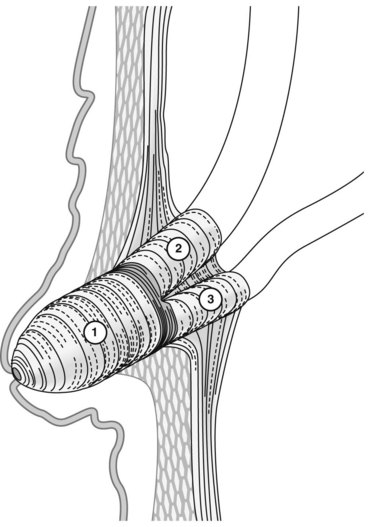

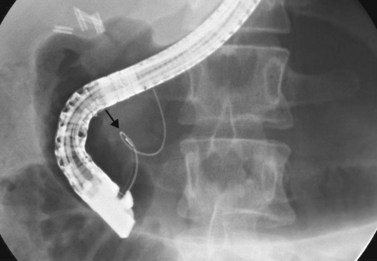

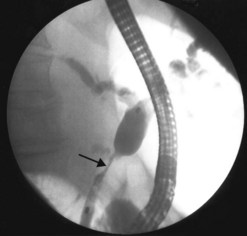

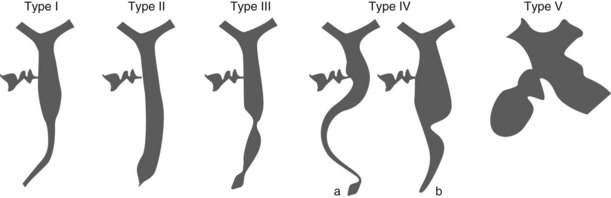

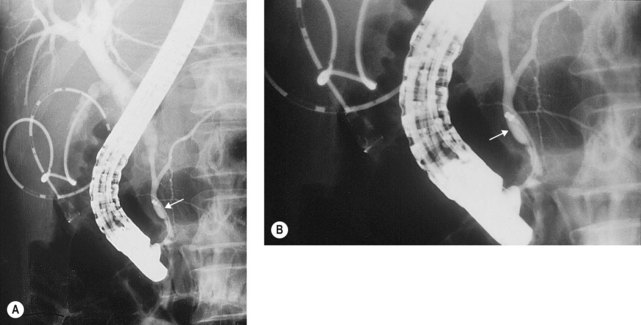

The common bile duct terminates at the ampulla of Vater, where it joins the main pancreatic duct (Wirsung’s duct) (Fig. 5). There are a number of variations in the communication between the common bile duct and Wirsung’s duct. It is important to be familiar with these variations when cannulating the papilla (Fig. 6). In the majority of cases (98%), the papilla has a single orifice (type I). The biliary duct and the pancreatic duct may have separate openings in the papilla (type II) (Fig. 7) or openings at different points in the duodenum (type III). There are two types of common opening (or common channel):

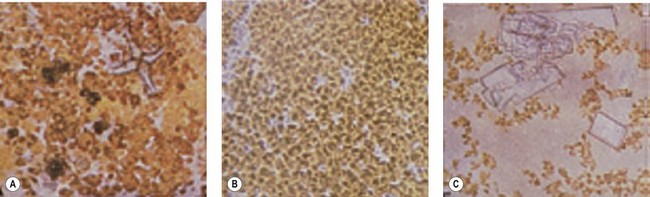

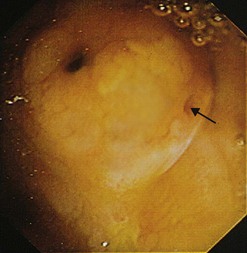

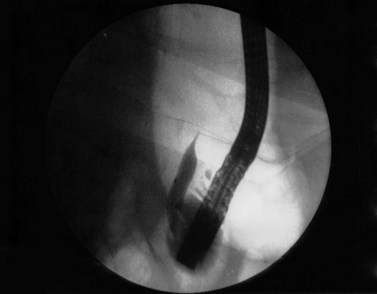

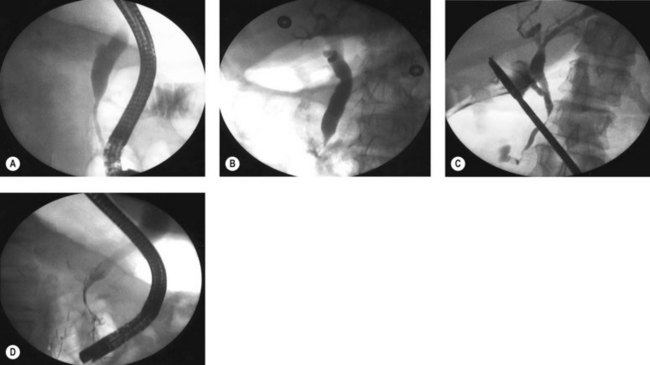

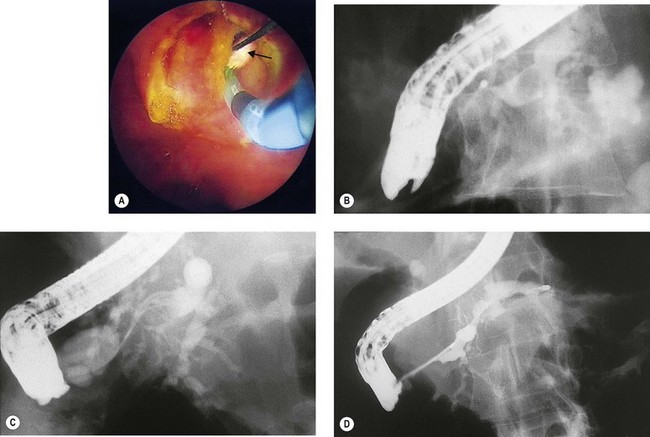

Figure 8 Type 1a common channel. These images illustrate a type 1a, with a long common channel (arrow).

The arterial supply of the papilla exhibits numerous anatomical variations, which are determined by the retroduodenal artery and the branch of the upper pancreaticoduodenal artery. Significant bleeding can occur depending on the configuration of the blood vessels at the papilla (Fig. 9).

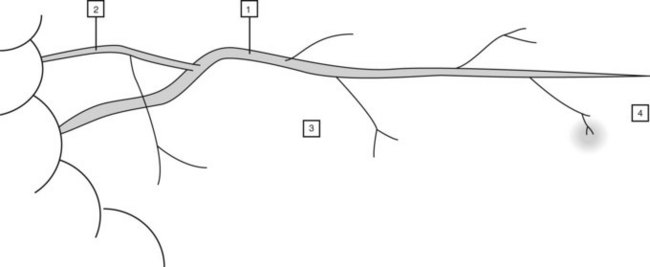

1.1 Normal pancreas and its variants

The main pancreatic duct rises steeply in the head, then crosses the upper abdomen horizontally or in a slightly ascending manner (Fig. 10). In healthy individuals, the shape of the pancreatic duct is variable, and diagnostic conclusions cannot be based on shape alone. Loops (ansa loops) may be observed, particularly in the isthmus (Fig. 11). The diameter of the pancreatic duct is on average 4 mm in the head of the pancreas, 3 mm in the body and 2 mm in the tail. The duct of Santorini usually connects the pancreatic duct to the accessory papilla. Collateral branches open perpendicular to the axis of the pancreatic duct. Their normal diameter should not exceed 1 mm. The diameter of the pancreatic duct increases with age. The aging of the pancreas is accompanied by irregularities in ductal diameter and may make differential diagnosis with incipient chronic calcifying pancreatitis difficult.

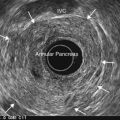

1.2 Congenital anomalies of the pancreatic ducts

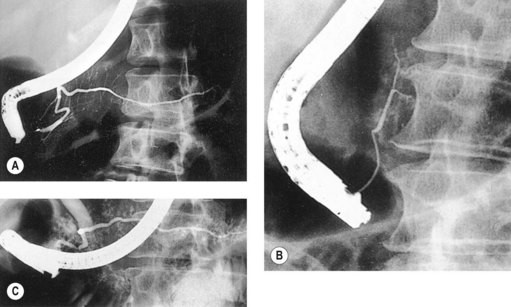

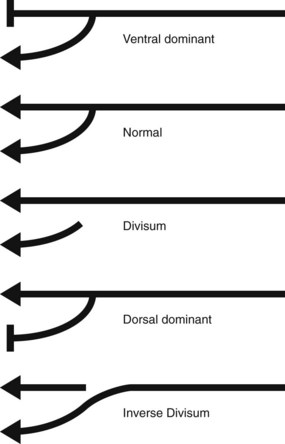

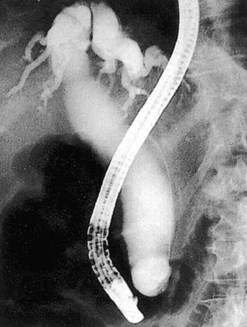

Pancreas divisum (Fig. 12) is the embryonic anomaly most commonly found in adults (5% of ERCP), characterized by the failure of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts to fuse. A definite diagnosis can be obtained only by cannulation of the major papilla and the accessory (minor) papilla.

Cannulation of the major papilla opacifies the ventral pancreas (Fig. 12B). The ventral duct is short with a small diameter. The length varies from a few millimetres to 5 or 7 cm. If the duct is very short, injection of contrast medium results very quickly in acinarization, which must not be confused with a submucosal injection. If the duct measures 3 or 4 cm, complete occlusion of the head of the pancreas by cancer must be excluded. Opacification of the dorsal pancreas (Fig. 12C) should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of pancreas divisum if the ventral pancreas is completely atrophic and invisible after catheterization of the major papilla. Opacification also allows visualization of lesions in the dorsal pancreas. Incomplete forms of pancreas divisum exist (Fig. 13).

2 Post-surgical anatomy

It is important to understand post surgical anatomy (see also Ch. 10.6), as it is encountered frequently due to the increase in obesity and gastric bypass surgery. Gastroduodenal anastomoses (Fig. 14) and certain types of choledochoduodenal anastomoses (Fig. 15) can usually be reached with a duodenoscope. The papilla is more difficult to reach in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy (Fig. 16). A pediatric colonoscope, enteroscope or double/single balloon or spiral enteroscopy may be required to reach the papilla. The main problem in these patients is the length of small bowel that has to be traversed. The shortest distance is encountered with a Billroth II (Fig. 17), with the longest distance typically associated with Roux-en-Y, associated with gastric bypass. Whether the limb has been placed antero- or retrocolic can also affect the ability to reach the papilla (Fig. 18). Retrocolic is associated with acute turns which can be difficult to negotiate but it’s a short way to find papilla. Anterocolic is a long way to reach papilla.

Box 1

Problematic surgical anatomy

From Haber GB. Double balloon endoscopy for pancreatic and biliary access in altered anatomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 66(3 Suppl):S47–S50, 2007.

10.9 ERCP imaging technique

4 Diagnostic problems and interpretation errors

4.1 Stones or bubbles?

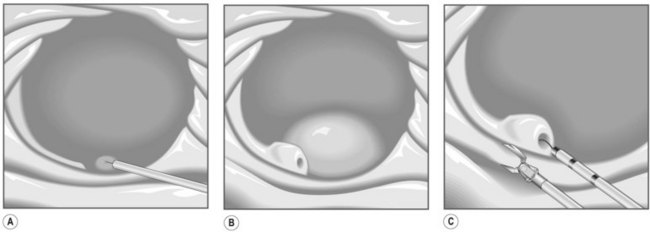

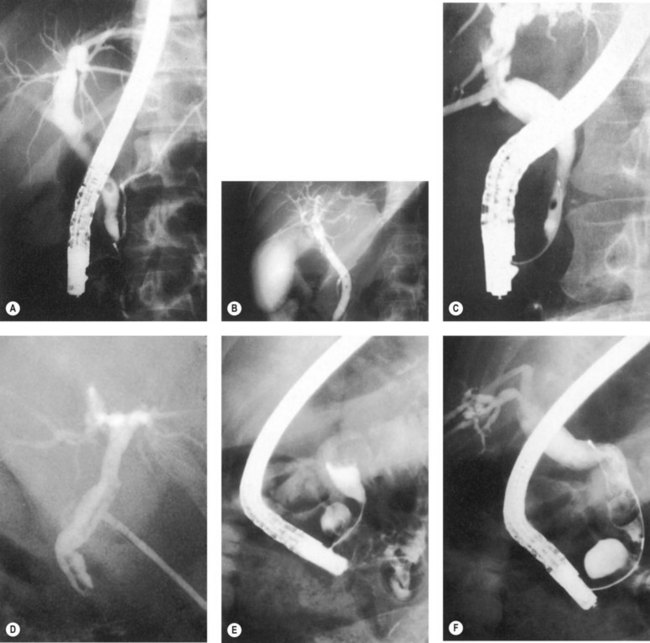

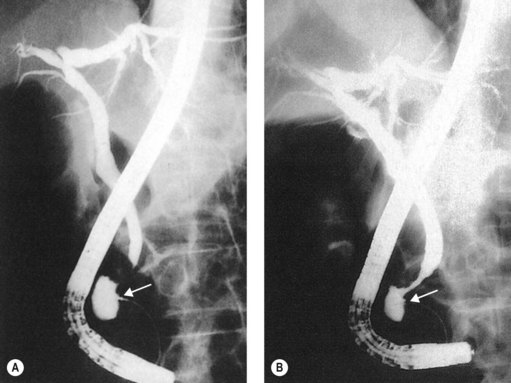

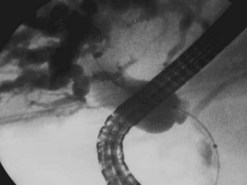

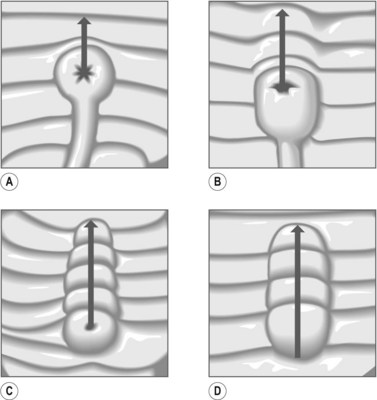

A filling defect corresponds in the majority of cases to a stone; however, occasionally it may be due to parasites (gallbladder with hydatid cyst, Ascaris, flukes), benign or malignant tumor fragments, hemobilia, or even air bubbles. To differentiate air bubbles from stones, tilt the table in such a way that the patient’s head is elevated (reverse Trendelenburg position). This will cause air bubbles to rise and stones to fall (Fig. 1).

Errors of interpretation can be reduced by some simple principles:

10.10 Abnormal imaging: classification and etiology

Key Points

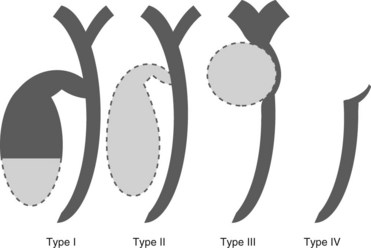

1 Cystic dilation of the bile duct

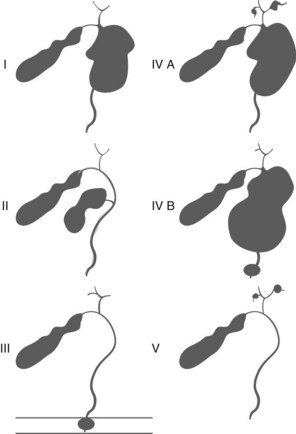

Congenital cysts of the bile duct are rare. They are classified depending on their location in the biliary tree (Table 1, Figs 1–4). They can be associated with jaundice, abdominal discomfort, cholelithiasis, cholangitis, hepatic abscesses, recurrent pancreatitis, cirrhosis, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and are associated with an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma.

Table 1 Classification of congenital bile duct cysts (Todani classification)

| Type of cyst | Definition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| I | Dilatation of the entire common hepatic or common bile duct or segments of each | Account for 80–90% of cysts. Treatment of choice is excision of the cyst and Roux-en-Y biliary-enteric anastomosis. |

| II | Diverticulum in the CBD | Surgical excision and primary closure over a T-tube. |

| III (choledochocele) | There is a dilatation of the intraduodenal portion of the CBD (Figs 2, 3) | <3 cm in diameter treat with sphincterotomy. ≥3 cm requires surgery. |

| IVa | Multiple dilatations of the intra- and extrahepatic biliary tree (Fig. 4) | Excision of the cyst and Roux-en-Y biliary-enteric anastomosis. No specific treatment of intrahepatic cysts. If disease is limited to specific intrahepatic segment these can be considered for surgical resection. |

| IVb | Multiple dilatations of the extrahepatic biliary tree | |

| V (Caroli disease) | Single or multiple intrahepatic cysts | If disease is limited to a single hepatic lobe, surgical resection can be considered. Transplantation can be considered in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. |

2 Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma can be classified into three types based on its radiographic appearance (Fig. 5):

3 Gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer can also be classified based on its radiographic appearance into types I–IV (Fig. 9). It is rare to find an irregular filling defect in the gallbladder without alteration of the common bile duct (Types I and II). Gallbladder cancer can present with Mirizzi’s syndrome (Type III). This radiographic appearance can also be due to cholecystitis, a stone impacted in the cystic duct or hepatic metastasis.

4 Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) causes diffuse strictures of the common bile duct and intrahepatic bile ducts. Alternating stenosis and dilation is characteristic. It is important to emphasize the difficulty of diagnosing diffuse bile duct cancer in this group of patients, thus, the importance of histological and cytological samples. Strictures of the pancreatic duct are rarer in PSC, occurring in 8% of patients, while cystic duct involvement occurs in 18%. PSC can be classified into four intrahepatic and four extrahepatic types depending on the radiographic features (Fig. 10).

4.1 Intrahepatic radiographic changes in PSC

5 Other causes of biliary dilation

7 Chronic pancreatitis

7.1 Pancreatographic alterations

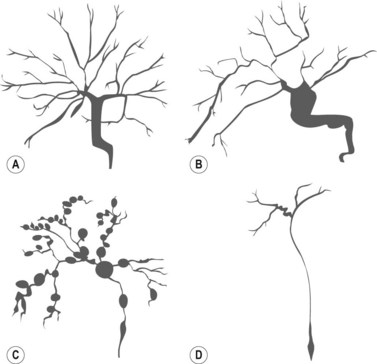

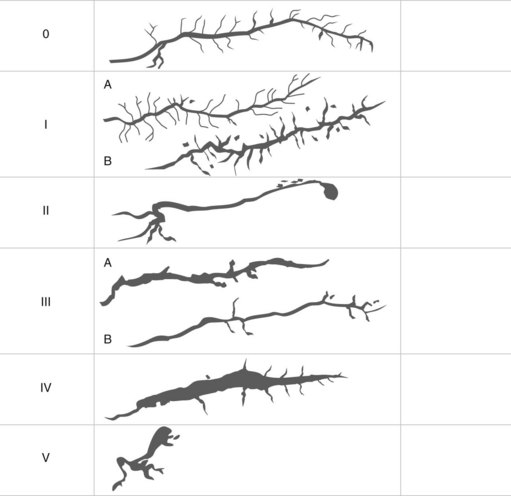

The main duct is often normal initially, with a few collateral branches demonstrating localized dilation. CT, functional and pancreatic tests are usually normal at this stage. Endoscopic ultrasound may show changes within the parenchyma before any ductal changes appear. The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis in the advanced form is rarely difficult: the main duct is dilated, tortuous and with defects (stones and protein deposits), stenosis and areas where the duct is disrupted. ERCP is useful in managing the complications of chronic pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis is usually graded using the Cambridge criteria (Table 2). Other classification systems used include the Kasugai classification (Box 1), and Crémer’s classification (Fig. 11).

| Grade | Main pancreatic duct | Side branches |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Equivocal | Normal | >3 abnormal |

| Mild | Normal | >3 abnormal |

| Moderate | Abnormal | >3 abnormal |

| Severe | Abnormal with at least one of the following: | >3 abnormal |

| Large cavity (>10 mm) | ||

| Duct obstruction | ||

| Intraductal filling defects | ||

| Severe dilation or irregularity |

Box 1 Kasugai’s classification of chronic pancreatitis

Kasugai’s classification distinguishes between three forms of the disease:

7.1.1 Crémer’s classification

Chronic pancreatitis can also affect the bile duct (Figs 12, 13). This can be classified into types I–IV depending on the radiographic appearance.

8 Pancreatic tumors

The image of both biliary and pancreatic stenosis is characteristic of pancreatic cancer. In typical cases, stenosis is present in the upper part of the intrapancreatic common bile duct with the same image shown in the cephalic pancreatic duct. The pancreatic ductal changes are shown in Figure 15 and can be classified as shown below. Types I and II are the most frequent. The other forms of pancreatic cancer are far less common.

Cremer M, Toussain J, Hermanu A, Deltenre M, de Toeuf J, Engelholm L. Les pancréatites chroniques primitives. Classification sur base de la pancreatographie endoscopique Acta, Gastroenterol Belg. 1976;39:522-546.

Liguory CI, Canard JM. Tumors of the biliary system. Clinics in Gastroenteroly. 1983;12(1):265-291.

Sarles H, Sarles JC, Guien C. Study of pancreatic and bile ducts in chronic pancreatitis. Arch Mal App Dig. 1958;47:664-683.

Ohto M, Ono T, Tsuchiya Y, Saisho H. Cholangiography and pancreatography. Tokyo New York: Ed. Igaku-Shoïn; 1978. pp 155-159

10.11 Endoscopic sphincterotomy

2 Biliary sphincterotomy technique

2.1 Standard technique

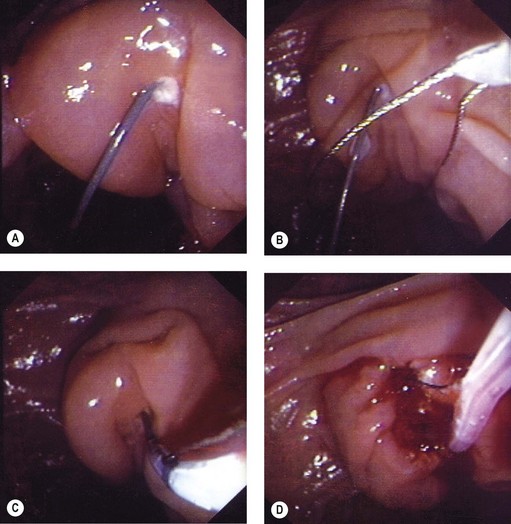

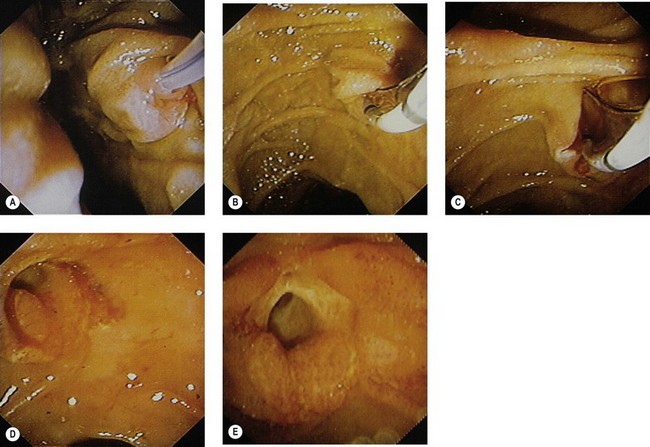

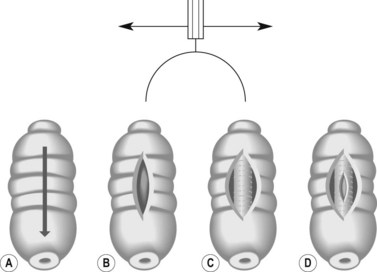

The standard technique was developed by Classen and Demling and consists of five steps:

3 Pancreatic sphincterotomy technique

3.1 Problems with sphincterotomy

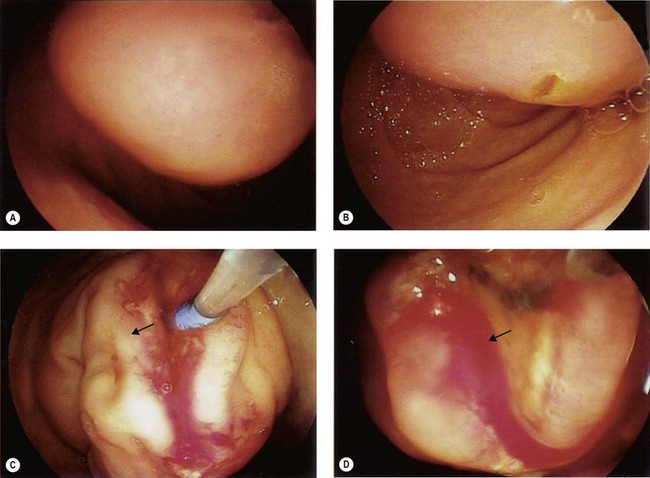

The average size of a sphincterotomy is between 10 and 15 mm. The papilla and the whole infundibulum (Figs 1D, 1E) should be cut until the lumen of the lower common bile duct is visible and/or air appears in the bile.

The average size of a sphincterotomy is between 10 and 15 mm. The papilla and the whole infundibulum (Figs 1D, 1E) should be cut until the lumen of the lower common bile duct is visible and/or air appears in the bile. The length of the incision depends on the endoscopic anatomy, the diameter of the bile duct, the length of the infundibulum (Figs 6) and if you are removing stones, their size.

The length of the incision depends on the endoscopic anatomy, the diameter of the bile duct, the length of the infundibulum (Figs 6) and if you are removing stones, their size. There are several methods to assess the adequacy of a biliary sphincterotomy. There should be rapid emptying of contrast from the bile duct into the second portion of the duodenum on imaging.

There are several methods to assess the adequacy of a biliary sphincterotomy. There should be rapid emptying of contrast from the bile duct into the second portion of the duodenum on imaging. The adequacy of the sphincterotomy depends on why it is being performed (i.e. to remove stones, etc.). Some general tips are:

The adequacy of the sphincterotomy depends on why it is being performed (i.e. to remove stones, etc.). Some general tips are:

4 Special situations

4.1 Sphincterotomy in patients with a gastroenteric anastomosis (Billroth II/Whipple)

Techniques

Equipment

Equipment is determined by which endoscope is used.

5 Sphincterotomy in difficult cases

5.1 Sphincterotomy over a guidewire

Where cannulation is difficult, a triple lumen sphincterotome is used to cannulate the bile duct with a guidewire (Fig. 10). Once the guidewire is deeply inserted into the duct, contrast is injected to confirm the correct duct. The sphincterotome is then advanced over the guidewire into the duct and sphincterotomy performed as described above.

5.2 Pre-cut

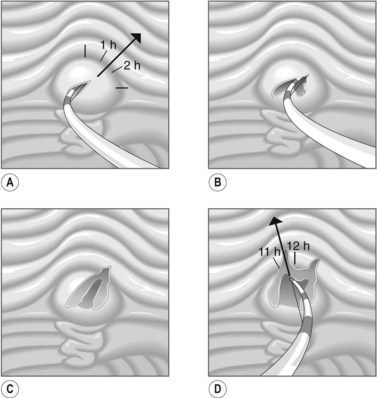

5.3 Needle knife infundibulotomy

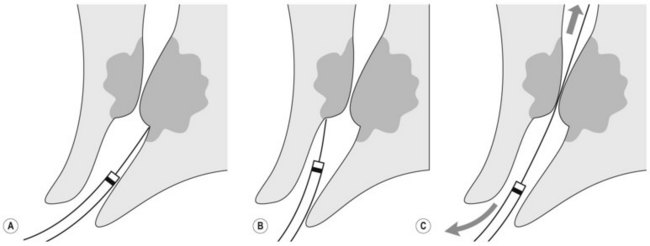

This involves cutting through the infundibulum to the bile duct. This technique should be used with a Type II or III infundibulum and should not be performed in a Type I or 0 infundibulum (Fig. 12). The ideal indication is a stone impacted in the papilla of Vater, where the stone serves as a block on which to open the infundibulum.

Technique (Figs 13, 14)

![]() Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

6 Endoscopic balloon dilation of the Sphincter of Oddi

Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5):1291-1299.

Kethu SR, Adler DG, Conway JD, et al. ERCP cannulation and sphincterotomy devices. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2010;71:435-445.

http://daveproject.org. This is an excellent site which provides videos on how to perform a sphincterotomy in normal, as well as altered, anatomy.

10.12 Biliary and pancreatic stone extraction techniques

Key Points

1 Bile duct stones

Box 3

Predictors of choledocholithiasis

(Reproduced with permission from Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2010.)

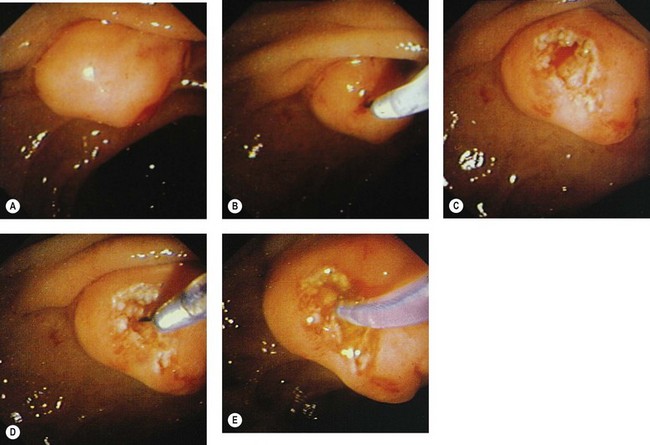

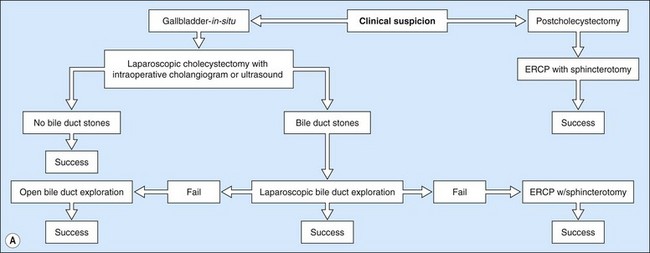

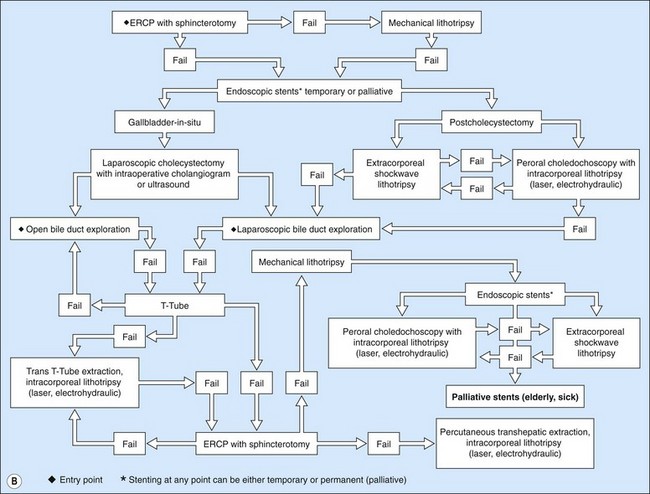

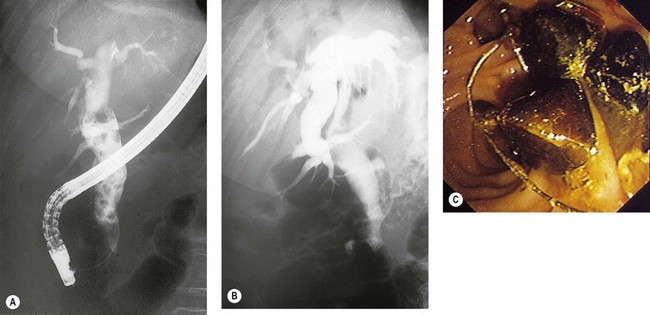

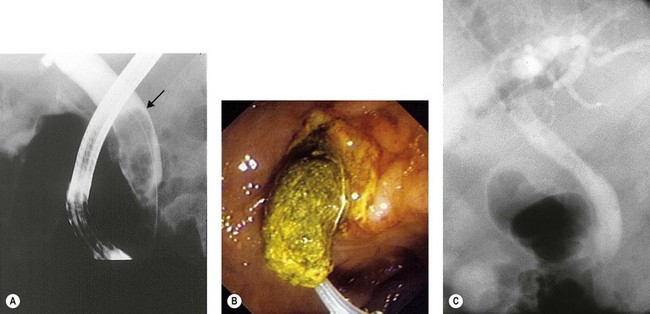

ERCP is the most common method for treating bile duct stones. Several methods can be used to remove stones; the choice of which method to use is determined by the experience of the endoscopist and the size of the stones. Very small stones (<5 mm) often pass spontaneously or can be removed with a balloon. Stones measuring between 5 and 15 mm can be removed either with a balloon or a basket. Giant stones (>1.5 cm) usually require mechanical lithotripsy to break them into smaller pieces before they can be removed. When stones are large, or where the patient’s anatomy makes stone extraction difficult, electrohydraulic or laser lithotripsy may be required. Laparoscopic bile duct exploration is an alternative to ERCP (Fig. 1). Prophylactic cholecystectomy should be offered to all patients following clearance of their bile duct, unless they are poor operative candidates.

![]() Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Gallstones

2 Pancreatic duct stones

3 Equipment

Specific equipment is required for lithotripsy, which is discussed later in this chapter.

4 Technique

4.1 Balloons

4.1.1 Balloon technique

In cases where there is a large stone but it is not possible to extend the sphincterotomy, a balloon sphincteroplasty can be used to dilate the os to allow the stones to be removed (see Chapter 10.11, Section 11.6).

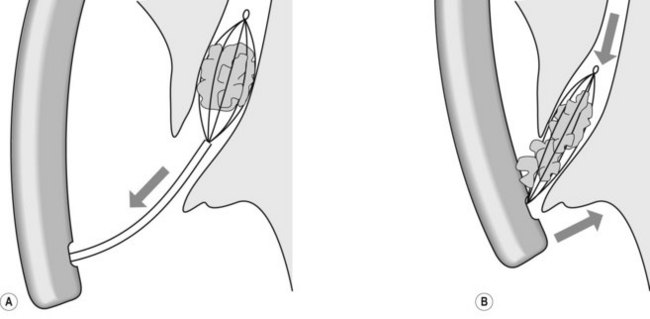

4.2 Stone extraction with a basket

4.2.1 Basket technique

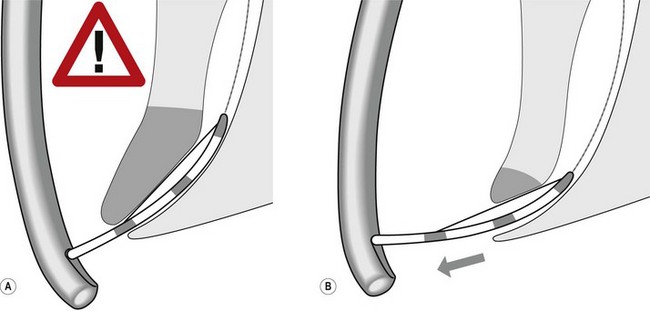

4.2.2 Problems with the Dormia basket

The stone is snared in the basket, which is impacted in the sphincterotomy opening.

Other options include extending the sphincterotomy, intra- or extracorporeal lithotripsy.

In cases where this fails, which is extremely rare, a nasobiliary drain can be inserted (see Chapter 10.19). The Dormia catheter is exteriorized like the nasobiliary drain. By pulling on it slightly every day, the stone and the Dormia become disimpacted within 48–72 h when the edema around the sphincterotomy subsides.

4.3 Reasons for failure to clear the bile duct of stones

![]() Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Management of intrahepatic stones

Avoid sphincterotomy unless definitive therapy is planned due to increased risk of recurrent cholangitis.

Avoid sphincterotomy unless definitive therapy is planned due to increased risk of recurrent cholangitis. Sometimes a small, light stone may be pushed into the intrahepatic bile ducts during injection. It is difficult to snare the stone in this situation. The fluoroscopy table can be raised or the patient placed in the decubitus position, which causes the stone to descend with gravity into the common bile duct, making it more accessible for extraction.

Sometimes a small, light stone may be pushed into the intrahepatic bile ducts during injection. It is difficult to snare the stone in this situation. The fluoroscopy table can be raised or the patient placed in the decubitus position, which causes the stone to descend with gravity into the common bile duct, making it more accessible for extraction.Box 5 Mirizzi’s syndrome