Chapter 24 Endoscopic plication techniques for the treatment of abdominal contour

Basic Science

The correction of the diastasis can be accomplished via a small video-assisted suprapubic incision, without skin resection, or by a mini-abdominoplasty in a technique described since 1971 by Callia, with a small infraumbilical skin resection. Other authors have already described, with variations, an infraumbilical plication only and no detachment of the umbilicus.1–7 There are also descriptions of a small incision in the umbilicus to facilitate the supraumbilical detachment2 and another approach that detached the umbilicus from the m. rectus.8,9 Since the introduction of video-endoscopy, indications for the correction of diastasis without skin resection can be extended to include, primarily, congenital diastasis and diastasis in men.10

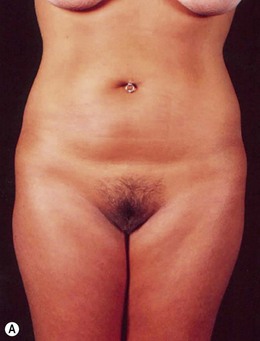

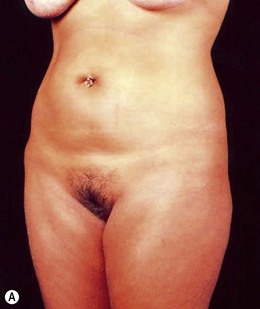

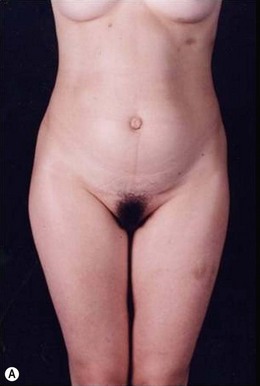

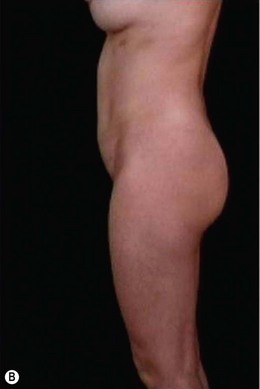

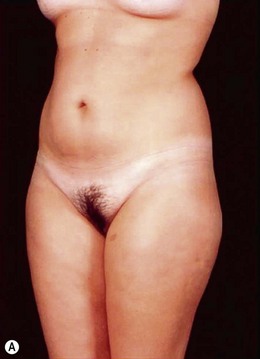

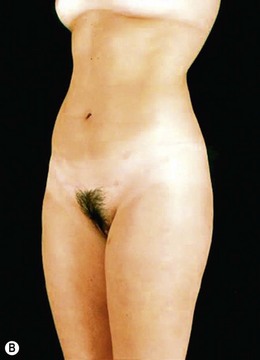

Indications for video-assisted mini-abdominoplasty are limited. This option must be precisely discussed with the patient because, on the one hand, there is the advantage of less scarring, but on the other hand, resection of skin is limited and there may be mild residual laxity both above and below the umbilicus. Another factor that should be considered in female patients is the possibility of pregnancy after surgery. In nulliparous patients who have abdominal flaccidity following weight loss (Figs 24.1 and 24.2), or in patients who have post-pregnancy abdominal flaccidity but are planning another pregnancy, this technique would be well indicated, because it doesn’t present the same limitations as classical abdominoplasty for postoperative pregnancy.

FIG 24.2 Appears ![]() ONLINE ONLY

ONLINE ONLY

Patient Selection

The selection of patients is subject to strict criteria:

• Patients with mild supra- and/or infraumbilical skin laxity, with diastasis of the rectus abdominis.

• High navel position, more than 14 cm above the pubis.

• Firm or minimally flaccid supraumbilical skin that will not allow the descent of the supraumbilical region to the suprapubic region.

• The possibility of post-abdominoplasty pregnancy, provided that the flaccidity is not excessive. These patients fall into Types III and IV of the Bozola and Psillakis classifications,1 and Type I in the Nahas classification system.4

• Diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle, which can either be acquired (post-pregnancy or following weight loss), or congenital, which can occur in both women and men (Figs 24.1–24.7).

FIG 24.4 Appears ![]() ONLINE ONLY

ONLINE ONLY

• Abdominal hernias (especially umbilical hernia) associated with lipodystrophy and skin flaccidity (Figs 24.8 and 24.9).

• Lipodystrophy and moderate skin flaccidity, where liposuction would offer limited results (Figs 24.10 and 24.11). Younger patients who have undergone massive weight loss resulting in abdominal flaccidity fall into this category, and also those with post-pregnancy flaccidity but who may become pregnant in the future (Figs 24.12 and 24.13).

Surgical Technique

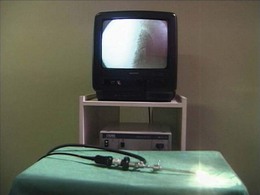

Materials for Video-endoscopy

Basic components for performing the procedures are:

• rigid endoscope, 4 or 10 mm (Figs 24.15 and 24.16)

• halogen or xenon light source (Fig. 24.15)

• retractor attachable to the endoscope (Fig. 24.16)

• dissection materials (Fig. 24.14)

• long endoscopic tweezers and scissors with cautery (Fig. 24.14)

FIG 24.15 Appears ![]() ONLINE ONLY

ONLINE ONLY

Methods for Creating and Maintaining the Optical Cavity

By separating the tissues in a cranial direction, the retractors serve a dual purpose: to expose the structures and to facilitate the dissection, using the tension exerted by the tissues not yet dissected. For this reason, the lens is 30° or 45°, to compensate for the rise of the optical tip, focusing the image in the margin of the optical cavity, where most of the dissection takes place. The 10 mm endoscopes may have a 0° angle, because they offer the greatest amplitude of image (Fig. 24.16).

Video-Assisted Technique

After completion of the plication, the navel is reinserted through the suture that was left in the midline, and plunged into the navel plication. This maneuver, described by Correa,11 gives a natural depth to the navel. It is important to fix the umbilicus in its new insertion point before resection of the skin, to achieve a precise result.

A 4.2 mm suction drain is placed, leaving a counter incision in the pubic region.

Postoperative Care

Smoking should be stopped at least 15 days pre-and postoperatively.

Regarding the recovery period, we see no great difference from classical abdominoplasty, contrary to those authors who advocate only an infraumbilical plication.7 Because of the dissection and muscle plication, the patient remains hospitalized for 24 hours, and should relax for 10 to 14 days, which is also important for prevention of seromas.

Outcomes, Prognosis, and Complications

Plication of the rectus abdominal with a minimal incision involves a central swordtail-pubic detachment, and may involve liposuction to accommodate the abdominal flap while preserving the lateral perforations, or even the Dílson Luz12 retractors, to release the flap from the lateral area without compromising the perforators, and avoiding excess skin above the navel.

Secondary Procedures

The most undesirable result is patient dissatisfaction with the surgical result, due to unrealistic expectations. Therefore, we should take enough time preoperatively, trying to understand the expectations of the patient, to avoid having to turn a mini-abdominoplasty into a classic abdominoplasty, due to patient dissatisfaction (Figs 24.17 and 24.18). Video-endoscopy has made a major contribution to the correction of diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles, umbilical and supraumbilical hernias. It enables hemostasis and plication of the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscle, avoiding a new incision at the umbilicus. This technical refinement facilitates surgery, reduces scarring and results in better outcomes.

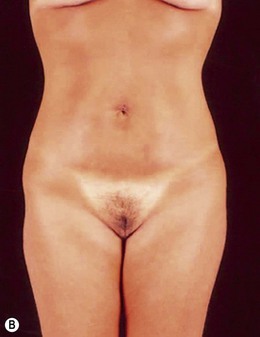

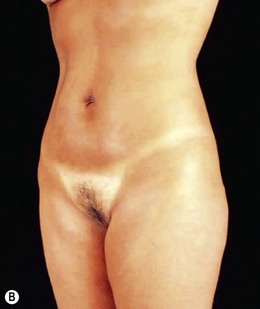

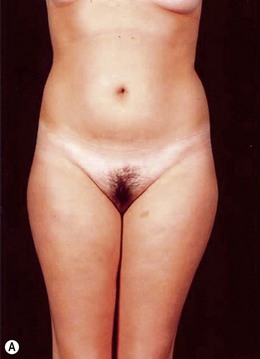

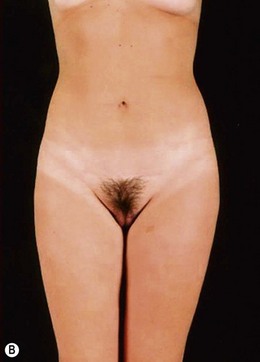

FIG. 24.18 Patient dissatisfied with mini-abdominoplasty and underwent subsequent classic abdominoplasty.

(A) Preoperative view (post mini-abdominoplasty); (B) Post classic abdominoplasty.

Another great advantage of this technique is the improved vascularization of the abdominal flap, because the detachment is more central, avoiding the costal margin, which preserves the upper pedicles (superior epigastric and intercostal arteries).13 This, coupled with less tension on the scar, due to limited resection of skin, reduces complications. Beyond that, the flap procedure in combination with abdominal liposuction does not increase risks, if performed carefully, and allows better accommodation of the flap over the plicated abdominal wall, especially above the navel. The applicability of this technique is related to precise indications and strict evaluation, to avoid patient dissatisfaction related not to the abdominal wall fixation, which is always satisfactory, but to skin excess, which is not tolerated by patients. When the indication, treatment of diastasis without excess skin, is correct, the result will always be pleasing for women or men.

1 Bozola AR, Psillakis JM. Abdominoplasty: a new concept and classification for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82(6):983–993.

2 Ferraro FJ, Zavitsanos GP, VanBuskirk ER, et al. Improving the efficiency, ease, and efficacy of endoscopic abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(3):895–898.

3 Greminger RF. The mini-abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79(3):356–364.

4 Nahas FX. A pragmatic way to treat abdominal deformities based on skin and subcutaneous excess. Aesth Plast Surg. 2001;25:365–371.

5 Restrepo JCC, Ahmed JAM. New technique of plication for miniabdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(3):1170–1179.

6 Wilkinson TS. Mini-abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82(5):917–918.

7 Wilkinson TS, Swartz B. Individual modifications in body contour surgery: the “limited” abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77(5):779–784.

8 Uebel CO. Miniabdominoplasty – a new approach for the body contouring. Presented at the 9th Annual Congress of the International Society of Aesthetic Surgery, New York, October 1987.

9 Uebel CO. Minilipoabdominoplastiy – its evolution. In: Saldanha OR, ed. Lipoabdominoplasty. Rio de Janeiro: DiLivros; 2006:73–85.

10 Lockwood T. Rectus muscle diastasis in males: primary indication for endoscopically assisted abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(6):1685–1693.

11 Correa MAMF. Videoendoscopic abdominoplasty (subcutanoscopic) – abdominal video plastic surgery. In: Badin AZ, Ferreira LM. Videoendoscopy in Body Contouring and Complementary Procedures. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2007:202–210.

12 Viterbo F. Undermining wands by Dilson Luz instruments with multiple applications. Progressive Undermining – Principles, Applications and Complementary Procedures. Luz DF, ed. Progressive Undermining – Principles, Applications and Complementary Procedures, vol 1. DiLivros: Rio de Janeiro, 2009:63–65.

13 O’Brien J. Endoscopic balloon-assisted abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(5):1462–1463.

Eaves FF, III., Nahai F, Bostwick J, III. Endoscopic abdominoplasty and endoscopically assisted mini abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:599.

Hay-Roe V. Seroma after lipoplasty with abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(5):997–998.

Iglesias M, Bravo L, Chavez-Muñoz C, et al. Endoscopic abdominoplasty: an alternative approach. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;57(5):489–494. PubMed PMID: 17060727.

Menz P. Pregnancy after abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(2):377–378.

Mest’ák J, Mest’ák O. Miniabdominoplasty. Acta Chir Plast. 2010;52(1):23–26. PubMed PMID: 21110499.

Nahai F, Brown GH, Vasconez LO. Blood supply to the abdominal wall as related to planning abdominal incisions. Am Surg. 1976;42:691.

Shestak KC. Marriage abdominoplasty expands the mini-abdominoplasty concept. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1021.

Uebel CO. Lipoabdominoplasty: revisiting the superior pull-down abdominal flap and new approaches. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33(3):366–376.

Zukowski ML, Ash K, Spencer D, et al. Endoscopic intracorporal abdominoplasty: a review of 85 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:516.