Chapter 52 Endoscopic Management of Post–Bariatric Surgery Complications

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Prototype Operating Endoscope

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Prototype Operating Endoscope

Introduction

As the field of bariatric surgery continues to grow in pace with the increasing prevalence of obesity, an increasing number of patients are referred for endoscopic evaluation after bariatric surgery. Endoscopic findings may represent the normal postsurgical appearance or a complication. A basic understanding of the anatomic changes and potential complications associated with bariatric procedures is essential for optimal endoscopic assessment and appropriate management. A thorough review of the surgical report and any relevant imaging studies are key elements for a successful endoscopic procedure.1 Recognizing that certain complications are unique to specific types of bariatric surgery allows for accurate diagnosis and therapy. Close communication and collaboration with the bariatric surgeon is strongly recommended before endoscopy, particularly when therapy is contemplated.

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

Marginal or Stomal Ulcers

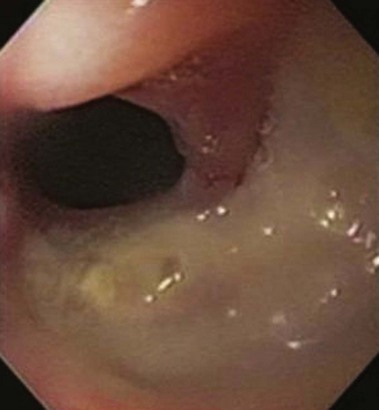

Marginal or stomal ulcers are ulcerations at the gastrojejunostomy that frequently occur on the jejunal side of the anastomosis (Fig. 52.1). Marginal ulcers may be seen in 16% of patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).2 Many ulcers remain subclinical, and the true incidence is likely higher. Ulceration can occur at any time but patients usually present within 3 months of surgery with pain, nausea, bleeding, or perforation.3,4 Several potential and controversial inciting factors are implicated, including gastrogastric fistula, large gastric pouch with inclusion of parietal cells and resultant acid exposure, ischemia, foreign body reaction to staples or nonabsorbable sutures at the anastomosis, Helicobacter pylori, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and gastric pouch orientation.5–7 The etiology is probably multifactorial with ischemia the likely culprit. Preoperative H. pylori testing and eradication is not routinely recommended because of conflicting data that this practice reduces the incidence of marginal ulceration.8,9 During upper endoscopy, the gastric pouch should be closely inspected for a gastrogastric fistula, and biopsy specimens should be obtained for H. pylori. Patients usually respond to treatment with proton pump inhibitors, liquid sucralfate, and H. pylori eradication therapy when appropriate.10,11 NSAIDs should be avoided, and smoking should be discontinued. Endoscopic removal of foreign material, such as nonabsorbable suture or staples, may help ulcer resolution. In cases of symptomatic refractory ulceration, surgical revision may be required.

Stomal Stenosis

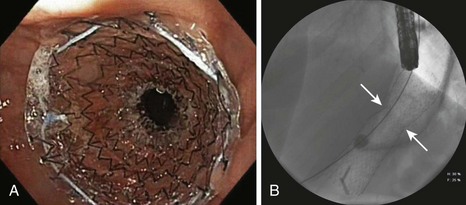

Stomal stenosis is an important complication that occurs in approximately 3% to 12% of patients after open RYGB and in 11% to 27% of patients after laparoscopic RYGB.2,4 Most strictures occur within the first year after surgery, with a mean time interval of 2 to 3 months to diagnosis.12,13 Patients present with nausea, vomiting, pain, or dysphagia. The exact mechanism for stricture formation is unknown, but ischemia, ulceration, subclinical anastomotic leak, circular stapler size, and surgical expertise are potential contributing factors.13,14 The gastrojejunostomy is intentionally created to be 11 to 15 mm in diameter. Although there is no clear definition for stomal stenosis, the latter is diagnosed when the luminal diameter is less than 10 mm or when passage of a standard upper endoscope through the anastomosis is met with resistance (Fig. 52.2).

In cases of symptomatic strictures, serial dilation using a through the scope balloon dilation catheter is preferred with the goal of achieving a stomal diameter of 10 to 12 mm. Dilation should not exceed 15 mm. The initial balloon size is based on the estimated diameter of the anastomotic stricture. Three sequential sizes may be inflated during one session, in keeping with the recommended “rule of 3’s” for stricture dilation. An effective dilation results in partial disruption of the anastomotic wall. Caution is warranted in the setting of coexistent marginal ulceration because of increased risk of perforation. Overzealous dilation, which can result in perforation or an overstretched anastomosis with resultant dumping syndrome and regain of weight, should be avoided. When a tight stricture precludes traversal with the endoscope and impairs visualization of the postanastomotic jejunal limbs, wire-guided through the scope balloon dilation under fluoroscopy is recommended. The reported perforation rate after balloon dilation approximates 2% to 3%.13,15 Small perforations can be managed conservatively.

Most (>90%) strictures are responsive to endoscopic balloon therapy.12,16 Most strictures can be effectively dilated in one or two sessions, but tight strictures may require several sessions. The time interval between sessions ranges from 1 to 3 weeks.15,16 The successful use of bougie dilators has been reported, but this technique requires guidewire placement within the jejunal Roux limb before dilation.17 Although temporary placement of a fully covered stent in selected patients with refractory strictures may be successful at achieving long-term stoma patency, a high rate of stent migration (>50%) has been observed in some studies (Fig. 52.3).18 If stent placement is contemplated, it is best to avoid dilating the stricture before stent placement to minimize the risk of migration. The duration of stent placement is typically 3 months. Other therapeutic techniques, including needle-knife electroincision of the anastomosis (which carries an increased risk of perforation) and intralesional steroid injection after balloon dilation, have been reported with some success.19,20 In the rare case in which endoscopic therapy is ineffective, surgical revision may be necessary. Patients with a modified RYGB with a Silastic ring around the proximal pouch to prevent dilation of the gastrojejunostomy may require surgical removal or replacement of the band.

Gastrogastric Fistula

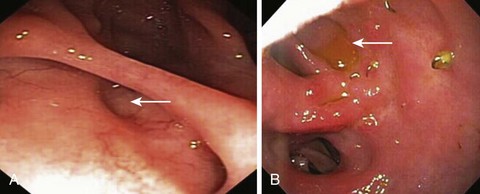

The reported incidence of staple line dehiscence with resultant gastrogastric fistula varies with the extent of division of the excluded stomach and is greater than 20% when the gastric pouch and bypassed stomach are undivided or partially divided to less than 5% when the segments are completely transected.21,22 Gastrogastric fistula denotes an abnormal communication between the neogastric pouch and the bypassed stomach. There are several postulated reasons for the development of fistulas, including surgical technique without complete division of the gastric pouch, marginal ulceration, anastomotic leak, and foreign body erosion.21,23 Even when the pouch is completely transected, a gastrogastric fistula can occur if the pouch is situated in close proximity to the bypassed stomach. Surgical interposition of omentum or a loop of jejunum between the segments may reduce this complication.24 Patients usually present with regain of weight, abdominal pain, or reflux symptoms. When a gastrogastric fistula is suspected, diagnosis is confirmed by upper endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal (GI) series, or in some instances abdominal computed tomography scan with oral contrast agent.

Gastrogastric fistulas are frequently small and easily overlooked. Endoscopically, a small gastrogastric fistula can appear as a diverticulum in the gastric pouch; larger fistulas allow endoscope passage into the excluded stomach (Fig. 52.4). When gastrogastric fistulas are associated with marginal ulceration, gastric biopsy specimens for H. pylori should be obtained. Barium studies are helpful in diagnosing small dehiscences. Most symptomatic patients require surgical intervention. However, in patients with small gastrogastric fistulas and associated marginal ulcers, an initial conservative approach consisting of proton pump inhibitor therapy, liquid sucralfate, or H. pylori eradication, as appropriate, may be effective.21,23 NSAID use and smoking should be strictly avoided. Patients are reevaluated after 4 to 8 weeks; if the fistula is healed, long-term use of a proton pump inhibitor is advised.21,23 In patients with small gastrogastric fistulas (<5 mm) who are unresponsive to medical therapy, endoscopic therapy, in the form of endoscopic suturing, argon plasma coagulation, fibrin glue injection, hemoclip application, or a combination thereof, may be considered given the reported successful outcome in small case series.23,25,26 Long-term follow-up data are awaited before any particular endoscopic therapy can be formally recommended for this select group of patients.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Early bleeding is uncommon after open bariatric surgery (<1%) compared with laparoscopic RYGB (1% to 4%).27–30 Bleeding is generally from the gastrojejunostomy. Endoscopic management of an early postoperative bleed is challenging because of the risk of perforation at the surgical anastomosis. In this setting, air insufflation should be minimized, and the use of nonthermal hemostatic devices, such as endoscopic clips, is preferred. Close collaboration with the surgeon is key for a successful outcome. Hematemesis is the most common clinical presentation in early bleeds.31 GI bleeding that occurs beyond the early postoperative period tends to occur from staple lines at the gastrojejunostomy (e.g., marginal ulcers), jejunojenunostomy, or bypassed stomach. Most patients are managed successfully with appropriate endoscopic therapy. Endoscopic therapy is achieved by standard hemostatic interventions such as injection, thermal, or mechanical modalities. Discontinuation of NSAIDs and testing for H. pylori serology are advised. Deep enteroscopy (e.g., balloon-assisted enteroscopy) is generally required to access the jejunojejunal anastomosis and enable retrograde examination of the bypassed stomach and duodenum. Patients presenting with obscure GI bleeding should be investigated for causes not related to the surgery, such as colonic pathology.

Food Impaction

Inadequate chewing and rapid ingestion of large food boluses, stomal stenosis, and motility disturbances result in food impaction.32,33 Retrosternal or abdominal pain and dysphagia are presenting symptoms. Food disimpaction is usually achieved by cautious push of the impacted food with the tip of the scope into the jejunal limb. Otherwise, piecemeal extraction through an overtube becomes necessary using accessories such as snares, nets, and grasping forceps. Care must be exercised not to traumatize the gastric pouch, anastomosis, or jejunal limbs. Gastric bezoars are a rare complication.34

Choledocholithiasis

Rapid weight loss predisposes bariatric patients to cholesterol gallstones. Within 6 months of surgery, 36% of patients develop new gallstones, and an additional 10% develop biliary sludge.5,35–37 Several causative factors have been suggested, including altered bile composition, cholesterol supersaturation of bile, gallbladder dysmotility, and loss of duodenal induced stimulation of gallbladder emptying.35–39 Although gallstones are prevalent in morbidly obese individuals, there is no consensus on the need for prophylactic cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy is generally performed in open RYGB but is not standard practice in laparoscopic RYGB, unless gallstones are diagnosed preoperatively. Elective cholecystectomy during bariatric surgery may contribute further to the symptoms of diarrhea and intolerance to fatty foods, and the occurrence of postoperative bile leaks poses a considerable challenge in these patients, in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is unsafe in the immediate postoperative period and a transhepatic approach is difficult in the absence of biliary dilation.19,40

Although new gallstones may be common, symptomatic gallstones occur infrequently (7%), and subsequent cholecystectomy is usually well tolerated in these patients.41,42 Choledocholithiasis after gastric bypass is uncommon. Diagnosis is usually based on abnormal liver tests, transabdominal ultrasound, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Performing ERCP in these patients is a challenging and arduous task. The procedure may be attempted by using a pediatric colonoscope, a balloon-assisted enteroscope, or a duodenoscope back-loaded onto a guidewire. Alternatively, a duodenoscope may be passed through a surgical, radiologic, or endoscopically guided gastrostomy or through a gastrogastric fistula.43,44 Laparoscopy-assisted transgastric ERCP allows quick access to the common bile duct with visualization of the papilla in the usual anatomic orientation.45

Anastomotic Leaks

Reported rates of anastomotic leaks are 0 to 5.6%.46,47 Endoscopy should be avoided in early anastomotic leaks, which can be life-threatening and may be associated with signs of toxicity such as tachycardia, fever, and leukocytosis. There is an increased risk of leak exacerbation or wound dehiscence with endoscopy. The mainstay of treatment is sepsis control and supportive care or surgical exploration in patients who are unstable.19,48 If the leak develops late with no signs of toxicity, endoscopic approaches may be considered. Enteral stents are an alternative therapeutic option with reported success.49 Data on the use of temporary enteral stent placement, fibrin glue, and hemoclips to seal leaks are limited.50,51 Additional long-term outcomes data are required before firm recommendations can be made on the efficacy and safety of these procedures in this setting.

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding

Band Erosion

Band erosion occurs in 1% to 11% of patients.2,52 Patients can present with infection at the access port site, pain, vomiting, bleeding, abdominal abscess, fistula, or sudden weight gain. Endoscopic removal of a near-complete penetration of a gastric band has been described, but surgical removal is strongly recommended.53 Caution must be exercised if endoscopic removal of a gastric band is considered, especially when the penetration through the gastric wall is incomplete because this carries a high risk of gastric perforation and peritonitis.

Pouch Dilation

The gastric pouch may dilate in approximately 12% of patients after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding owing to proximal herniation of the stomach.5,54 Deflation of the band resolves this problem in most cases. Endoscopy is of no therapeutic value in this setting.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Acid reflux is common with a reported increase in acid regurgitation from 13% to 69% after band placement.55 The prevalence of postoperative esophagitis was 75% in one study.55 Initial management consists of acid suppression therapy combined with sucralfate; surgical revision is considered in unresponsive patients.

Vertical Banded Gastroplasty

Band Erosion

Approximately 1% to 2% of patients with vertical banded gastroplasty develop band erosion.2,56 Patients tend to present with weight gain and to a lesser extent abdominal pain. Surgical consultation should be sought in these patients, who generally require reoperation or conversion to RYGB.

Staple Line Dehiscence

Staple line disruption in vertical banded gastroplasty results in failure to lose weight rather than ulceration. Staple line dehiscence has been described after blunt abdominal trauma.57 Endoscopy is helpful in diagnosing and evaluating the disruption. Patients should be referred for surgical revision to RYGB.

Sleeve Gastrectomy and Duodenal Switch

Anastomotic Leaks

Data are limited on the endoscopic management of anastomotic leaks after sleeve gastrectomy alone or in combination with duodenal switch. Similar to leaks seen with other bariatric procedures, operative treatment is the mainstay for patients with signs of sepsis and hemodynamic instability unresponsive to conservative management. Successful treatment of gastric leaks at the gastroesophageal junction using temporary coated self-expanding stents in stable patients was reported in a small study.58

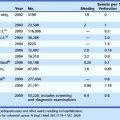

Indications for Endoscopy

Tables 52.1 and 52.2 summarize findings from studies that have evaluated indications for endoscopy and endoscopic findings after RYGB and laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty.24,32,60 After RYGB, 20% to 30% of patients developed upper GI symptoms that prompted endoscopy; 15% of endoscopic procedures performed within the first 6 months were normal compared with 53% of procedures performed beyond 6 months. Upper GI bleeding and dysphagia were more likely to be associated with endoscopic abnormalities, whereas normal endoscopic findings were more commonly reported with epigastric pain.

Table 52.1 Indications for Endoscopy after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) and Laparoscopic Vertical Banded Gastroplasty (LVBG)

| RYGB | LVBG | |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 30%–53% | 42% |

| Nausea and vomiting | 35%–62% | 50% |

| Dysphagia | 4%–16% | 13.2% |

| GI bleed | 12% | 9.2% |

| Weight regain | 6% | — |

| Heartburn | 2% | 29% |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 52.2 Endoscopic Findings after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) and Laparoscopic Vertical Banded Gastroplasty (LVBG)

| RYGB | LVBG | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 43%–44% | 41.4% |

| Marginal ulcer | 27%–36% | 7.2% |

| Stomal stenosis | 13%–19% | 9.9% |

| Staple line dehiscence | 4%–16% | — |

| Esophagitis | 3% | 18% |

Experimental Therapies

Gastric pouch or gastrojejunostomy dilation after RYGB can result in weight regain. There is a 5% to 13% rate of major complications after reoperation for weight regain.61 Early promising data on the use of StomaphyX (EndoGastric Solutions, Redmond, WA) showed reduction in gastric pouch size with resultant weight loss.62 Minor self-limiting complications of sore throat and epigastric pain were noted. The device uses polypropylene H-fasteners to create full-thickness, serosa-to-serosa tissue apposition. Successful use of the StomaphyX device to repair gastric pouch leaks was reported in a small case series.63 Data from a small pilot study suggest that endoscopic suturing using the EndoCinch device (C.R. Bard, Murray Hill, NJ) to tighten dilated gastrojejunal anastomoses is technically feasible and safe and may lead to weight loss in some patients.64 Prospective controlled trials are essential to validate efficacy, safety, and durability of emerging endoscopic therapies before use in clinical practice.

1 Feitoza AB, Baron TH. Endoscopy and ERCP in the setting of previous upper GI tract surgery. Part I. Reconstruction without alteration of pancreaticobiliary anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:743-749.

2 Huang CS, Farraye FA. Endoscopy in the bariatric surgical patient. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:151-166.

3 MacLean LD, Rhode BM, Nohr C, et al. Stomal ulcer after gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:1-7.

4 Sanyal AJ, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, et al. Stomal complications of gastric bypass: Incidence and outcome of therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1165-1169.

5 Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD, et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2571-2580.

6 Sapala JA, Wood MH, Sapala MA, et al. Marginal ulcer after gastric bypass: A prospective 3-year study of 173 patients. Obes Surg. 1998;8:505-516.

7 Pope GD, Goodney PP, Burchard KW, et al. Peptic ulcer/stricture after gastric bypass: A comparison of technique and acid suppression variables. Obes Surg. 2002;12:30-33.

8 Papasavas PK, Gagné DJ, Donnelly PE, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and value of preoperative testing and treatment in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:383-388.

9 Rasmussen JJ, Fuller W, Ali MR. Marginal ulceration after laparoscopic gastric bypass: An analysis of predisposing factors in 260 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1090-1094.

10 Gumbs AA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Incidence and management of marginal ulceration after laparoscopic Roux-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:460-463.

11 Dallal RM, Bailey LA. Ulcer disease after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:455-459.

12 Ovsiowitz M, Kanagarajan N, Ahmad AS. Endoscopic issues in the post-gastric bypass patient. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:121-132.

13 Mathew A, Veliuona MA, DePalma FJ, et al. Gastrojejunal stricture after gastric bypass and efficacy of endoscopic intervention. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1971-1978.

14 Ukleja A, Afonso BB, Pimentel R, et al. Outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation of strictures after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1746-1750.

15 Go MR, Muscarella P2nd, Needleman BJ, et al. Endoscopic management of stomal stenosis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:56-59.

16 Peifer KJ, Shiels AJ, Azar R. Successful endoscopic management of gastrojejunal anastomotic strictures after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:248-252.

17 Fernández-Esparrach G, Bordas JM, Llach J, et al. Endoscopic dilation with Savary-Gilliard bougies of stomal strictures after laparosocopic gastric bypass in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2008;18:155-161.

18 Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM, et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:935-938.

19 Obstein KL, Thompson CC. Endoscopy after bariatric surgery (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1161-1166.

20 Catalano MF, Chua TY, Rudic G. Endoscopic balloon dilation of stomal stenosis following gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17:298-303.

21 Carrodeguas L, Szomstein S, Soto F, et al. Management of gastrogastric fistulas after divided Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: Analysis of 1,292 consecutive patients and review of literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1:467-474.

22 Capella JF, Capella RF. Gastro-gastric fistulas and marginal ulcers in gastric bypass procedures for weight reduction. Obes Surg. 1999;9:22-28.

23 Gumbs AA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Management of gastrogastric fistula after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:117-121.

24 Huang CS, Forse RA, Jacobson BC, et al. Endoscopic findings and their clinical correlations in patients with symptoms after gastric bypass surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:859-866.

25 Gonzalez R, Nelson LG, Gallagher SF, et al. Anastomotic leaks after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1299-1307.

26 Shikora SA, Kim JJ, Tarnoff ME. Reinforcing gastric staple-lines with bovine pericardial strips may decrease the likelihood of gastric leak after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:37-44.

27 Nguyen NT, Longoria M, Chalifoux S, et al. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1308-1312.

28 Fernández-Esparrach G, Bordas JM, Pellisé M, et al. Endoscopic management of early GI hemorrhage after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:552-555.

29 Nguyen NT, Rivers R, Wolfe BM. Early gastrointestinal hemorrhage after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:62-65.

30 Steffen R. Early gastrointestinal hemorrhage after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:466-467.

31 Jamil LH, Krause KR, Chengelis DL, et al. Endoscopic management of early upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:86-91.

32 Yang CS, Lee WJ, Wang HH, et al. Spectrum of endoscopic findings and therapy in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1232-1237.

33 Stellato TA, Crouse C, Hallowell PT. Bariatric surgery: Creating new challenges for the endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:86-94.

34 Pinto D, Carrodeguas L, Soto F, et al. Gastric bezoar after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16:365-368.

35 Iglézias Brandão de Oliveira C, Adami Chaim E, da Silva BB. Impact of rapid weight reduction on risk of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2003;13:625-628.

36 Gustafsson U, Benthin L, Granström L, et al. Changes in gallbladder bile composition and crystal detection time in morbidly obese subjects after bariatric surgery. Hepatology. 2005;41:1322-1328.

37 Tucker O, Soriano I, Szomstein S, et al. Management of choledocholithiasis after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:674-678.

38 Gebhard RL, Prigge WF, Ansel HJ, et al. The role of gallbladder emptying in gallstone formation during diet-induced rapid weight loss. Hepatology. 1996;24:544-548.

39 Shiffman ML, Shamburek RD, Schwartz CC, et al. Gallbladder mucin, arachidonic acid, and bile lipids in patients who develop gallstones during weight reduction. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1200-1208.

40 Hamad GG, Ikramuddin S, Gourash WF, et al. Elective cholecystectomy during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Is it worth the wait? Obes Surg. 2003;13:76-81.

41 Villegas L, Schneider B, Provost D, et al. Is routine cholecystectomy required during laparoscopic gastric bypass? Obes Surg. 2004;14:206-211.

42 Liem RK, Niloff PH. Prophylactic cholecystectomy with open gastric bypass operation. Obes Surg. 2004;14:763-765.

43 Baron TH. Double-balloon enteroscopy to facilitate retrograde PEG placement as access for therapeutic ERCP in patients with long-limb gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:973-974.

44 Martinez J, Guerrero L, Byers P, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and gastroduodenoscopy after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1548-1550.

45 Dapri G, Himpens J, Buset M, et al. Laparoscopic transgastric access to the common bile duct after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1646-1648.

46 Fernandez AZJr, DeMaria EJ, Tichansky DS, et al. Experience with over 3,000 open and laparoscopic bariatric procedures: Multivariate analysis of factors related to leak and resultant mortality. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:193-197.

47 Higa KD, Boone KB, Ho T. Complications of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 1,040 patients—what have we learned? Obes Surg. 2000;10:509-513.

48 Lee CW, Kelly JJ, Wassef WY. Complications of bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:636-643.

49 Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM, et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:935-938.

50 Merrifield BF, Lautz D, Thompson CC. Endoscopic repair of gastric leaks after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A less invasive approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:710-714.

51 Salinas A, Baptista A, Santiago E, et al. Self-expandable metal stents to treat gastric leaks. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:570-572.

52 Abu-Abeid S, Keidar A, Gavert N, et al. The clinical spectrum of band erosion following laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:861-863.

53 De Palma GD, Formato A, Pilone V, et al. Endoscopic management of intragastric penetrated adjustable gastric band for morbid obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4098-4100.

54 Galvani C, Gorodner M, Moser F, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Ends justify the means? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:934-941.

55 Ovrebø KK, Hatlebakk JG, Viste A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in morbidly obese patients treated with gastric banding or vertical banded gastroplasty. Ann Surg. 1998;228:51-58.

56 Greve JW. Surgical treatment of morbid obesity: Role of the gastroenterologist. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2000;232:60-64.

57 Oyogoa S, Komenaka I, Wise L. Vertical banded gastroplasty staple-line dehiscence after blunt trauma to the abdomen. Obes Surg. 2000;10:61-63.

58 Serra C, Baltasar A, Andreo L, et al. Treatment of gastric leaks with coated self-expanding stents after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2007;17:866-872.

59 Eisendrath P, Cremer M, Himpens J, et al. Endotherapy including temporary stenting of fistulas of the upper gastrointestinal tract after laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Endoscopy. 2007;39:625-630.

60 Wilson JA, Romagnuolo J, Byrne TK, et al. Predictors of endoscopic findings after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2194-2199.

61 Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Steele SR, et al. A case-match analysis of failed prior bariatric procedures converted to resectional gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2004;187:666-670.

62 Mikami D, Needleman B, Narula V, et al. Natural orifice surgery: Initial US experience utilizing the StomaphyX device to reduce gastric pouches after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:223-228.

63 Overcash WT. Natural orifice surgery (NOS) using StomaphyX for repair of gastric leaks after bariatric revisions. Obes Surg. 2008;18:882-885.

64 Thompson CC, Slattery J, Bundga ME, et al. Peroral endoscopic reduction of dilated gastrojejunal anastomosis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. A possible new option for patients with weight regain. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1744-1748.