CHAPTER 133 Endoscopic Discectomy and Foraminal Decompression

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic disc surgery is evolving rapidly because of improvements in surgical technique, endoscope design, adjunctive surgical tools, and instrumentation. New endoscopes and complementary surgical devices enhance the endoscopic spine surgeon’s ability also to probe spinal anatomy in a conscious patient. The surgeon can then evolve his or her diagnostic and surgical skills with this newly found ability to evaluate pathologic, anatomic, and physiologic processes causing the patient’s pain. Now that diagnostic spinal endoscopy can be performed, conditions previously not even considered for surgery may be probed, evaluated, and surgically treated, and perhaps with greater accuracy. We believe that our understanding of discogenic back pain is enhanced by this ability to endoscopically visualize lesions not previously seen intradiscally and in the ‘hidden’ extra-foraminal zone.1 Spinal endoscopy is poised to parallel the development and evolution of knee, shoulder, and ankle arthroscopy.2 Without endoscopy, spine surgeons must depend heavily on imaging systems that, while extremely sensitive in identifying pathologic conditions, do not always correlate that condition with the patient’s pain.

Interventional pain management complementing endoscopic surgery

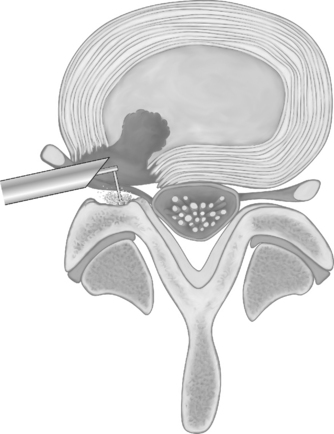

Foraminal epidurography and foraminal therapeutic injections can be performed using a needle technique that mimics the surgical approach to the foramen and spinal canal.3 The approach differs from traditional interventional pain management ‘down the tunnel’ approaches because it is the same far lateral approach used by endoscopic spinal surgeons to access the foramen for endoscopic surgery. The tip of the needle is directed into Kambin’s triangle between the exiting and traversing nerve root, rather than at the shoulder of the exiting nerve root. If non-ionic contrast agent (i.e. Isovue 300) is injected to outline the foramen, it should be able to identify the location and position of the traversing and exiting nerves that cross each spinal level (Fig. 133.1). Anomalous configurations such as conjoined nerves or furcal nerves provide additional information regarding the anatomy of the lumbar spine. In fact, these anomalies are rarely observed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) but are routinely visualized with spinal endoscopy in the ‘hidden zone’ or far lateral zone of the foramen.1,18,19 Diagnostic and therapeutic information gleaned from these modified injection procedures can be used by the surgeon to better select patients for surgical intervention. Patients with symptomatic disc protrusions, annular tears, and foraminal stenosis may first be diagnosed by discography followed by foramino-epidurography, then get relief with the therapeutic foraminal injection. If the response is favorable but short lived, the diagnostic and therapeutic process will help the surgeon with patient selection. As a bonus, the epidurogram will help determine the ease and feasibility of endoscopic surgery because it allows for a trial needle placement into the foramen before surgical intervention.

Endoscopic surgery following injection therapy

Patients who experience temporary relief with injection procedures directed toward the pain generator may realize definitive relief with endoscopic or surgical correction of the pathoanatomy. Our treatment process entails directing a needle to the pain generator, desensitizing or anesthetizing it, dilating a path that will allow a tubular retractor to be inserted, followed by an operating endoscope. Evocative discography™ is helpful in identifying the disc as a pain generator in axial back pain and sciatica.4 When spinal endoscopy and probing complements discography performed with the patient in an aware state, the pathoanatomy and normal anatomy can be visually correlated with imaging studies. In the authors’ experience, new information or information different from the MRI interpretation occurs 30% of the time.4

INDICATIONS

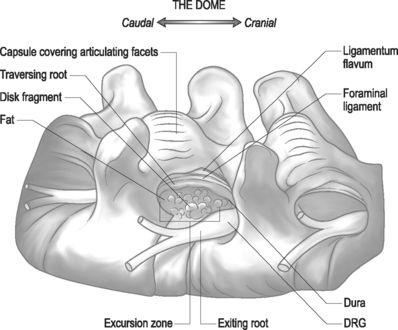

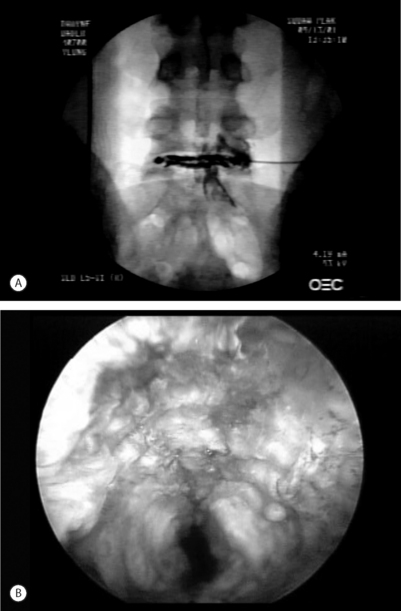

In general, the indications for diagnostic and/or therapeutic endoscopy require a pathologic lesion that is accessible, visible, treatable, or requires endoscopic confirmation through the foramen.5 Limitations of the surgeon’s skill and/or experience with the endoscopy or difficult spinal anatomic are the primary contraindications, exclusive of comorbidities such as infection or uncontrolled coagulopathy.6 For herniations from T10 to L4, the foraminal approach provides excellent access to the disc and epidural space (Fig. 133.2). At L5–S1, anatomic restrictions may cause the surgeon to opt for the posterior transcanal approach. As surgeon experience increases, anatomy that previously precluded spinal endoscopy is no longer a barrier.7 Anatomic structures within reach of the spine endoscope transforaminally are illustrated in Figure 133.3.

Disc herniation

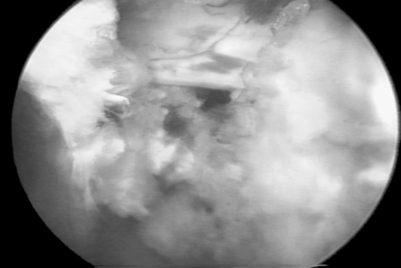

Symptomatic disc herniation is the most common indication, with surgical decompression limited only by the accessibility of endoscopic instruments to the herniated fragment.8,9 The posterolateral foraminal approach is ideal for a far lateral, extraforaminal disc herniation. Traditional surgical approaches to far lateral, extraforaminal disc herniations are more difficult, requiring a paramedian incision through the vascular intertransverse ligament. This surgical area is often termed the ‘hidden zone.’1 Although the lateral zone of the disc can be accessed with a paramedian incision, in our view, it is easier to access the extraforaminal zone endoscopically via the posterolateral portal. A typical foraminal view of nucleus pulposus extruded past the posterior annulus is shown (Fig. 133.4). In our experience, this is the preferred approach for disc herniations in the upper lumbar and lower thoracic spine since the transcanal approach will require more extensive laminectomy that may destabilize the spinal segment if the herniation is above L3–4.

Discitis

Endoscopic excisional biopsy and disc space debridement is ideal for surgically debriding infectious discitis (Fig. 133.5).10 With this technique the surgeon will not have to be overly concerned about creating dead space for the inflamed or infected disc material to spread into the dead space created by a posterior approach. The clinical results are dramatic and, we believe, tissue biopsy is more accurate than needle aspiration in identifying the cause of discitis. In our experience, even sterile discitis will benefit from intradiscal debridement and irrigation.

Lateral recess and central stenosis

Endoscopic foraminoplasty by endoscopic techniques can be accomplished by experienced endoscopic surgeons.6,11,12 Although trephines, rasps, and burrs can be utilized, the Ho:YAG laser has enhanced the procedure technically, as laser is a very precise cutting tool for visually controlled soft tissue and bone ablation. Endoscopic laser foraminoplasty (ELF) has an inherent advantage over classic surgery as it will not produce further instability (Fig. 133.6).13 With endoscopy, the foramen can be enlarged up to 45.5% versus the 34.2% attainable with the standard posterior technique of removing only the medial one-third of the facet. As well, posterior decompression of the lamina with removal of the medial one-third of the facet will produce increased extension and axial rotation postoperatively.13 In comparison, endoscopic foraminoplasty has not been shown to cause increased instability, even in spondylolisthesis.12 The technique is most useful for lateral recess stenosis. In central spinal stenosis, when there is concomitant posterior disc protrusion, decompression of the spinal canal can be effectively accomplished by resecting the bulging annulus in a collapsed disc, thus lowering the floor of the foramen without destabilizing the spinal segment. In isthmic spondylolisthesis, when there is more leg pain than back pain, this is usually due to impingement on the exiting nerve by the pars pseudoarthrosis defect. The goal in this instance is to decompress the compromised exiting nerve by elevating the dome formed by the undersurface of the superior articular facet and lamina without further destabilizing the spinal segment (Fig. 133.7).

Recurrent disc herniation

We have observed that patients with recurrent pain following a discectomy may have a small and seemingly trivial recurrent disc herniation. In these cases, the recurrent disc herniation may cause pain out of proportion to the size of the herniation. This is, we suspect, due to either direct contact of the inflammation producing nucleus pulposus to the nerve or the traversing nerve being tethered to the epidural scar, resulting in the inability of the nerve to give way to the disc fragment. Posterolateral endoscopic discectomy avoids dissecting through scar tissue from the previous trans-canal posterior approach. The surgeon is also able to access the disc through virgin tissue and grab the herniated nucleus from the ventral side and remove it. In endoscopic discectomy, especially with indigo carmine staining, the fragment is readily visible for extraction through the foramen. The results of endoscopic decompression for previous transcanal or endoscopic discectomy is as good as the original index procedure.12,14

CURRENT IMAGING METHODS

In the authors’ experience, our imaging studies are only about 70% accurate and specific for predicting pain.5,12,14–17 Conditions such as lateral annular tears, rim tears, endplate separation, small subligamentous disc herniations, anomalous nerves in the foramen, and miscellaneous discogenic conditions are cumulatively missed about 30% of the time. These conditions are diagnosable and often treatable with spinal endoscopy. Tears that are in the lateral and ventral aspect of the disc are sometimes missed by MRI studies. Very small disc herniations that protrude past the outer fibers of the annulus are also missed, since the fragment may be flattened against the posterior longitudinal ligament or nerve, appearing on the MRI as a thickened or bulged annulus, but really containing a subligamentous herniation. In rare circumstances, when the nerve root appears ‘swollen’ or enlarged, the MRI may not be capable of distinguishing a swollen nerve from a conjoined nerve or a nerve with an adherent fragment of disc. Endoscopy allows for direct visualization of such a ‘swollen root,’ thereby enhancing our ability to diagnose and subsequently treat this entity. We have observed that when the disc tissue is in direct contact with a nerve, the nerve can be irritated and a painful inflammatory membrane forms. When an inflammatory membrane is present, the pain pattern can be confusing. Diagnostic spinal endoscopy has confirmed ‘nondermatomal’ pain in scores of patients with proximal thigh, buttock, and groin pain at levels distal to the root origin of the anatomic area. Removal of the source of irritation can diminish or abate painful symptoms.

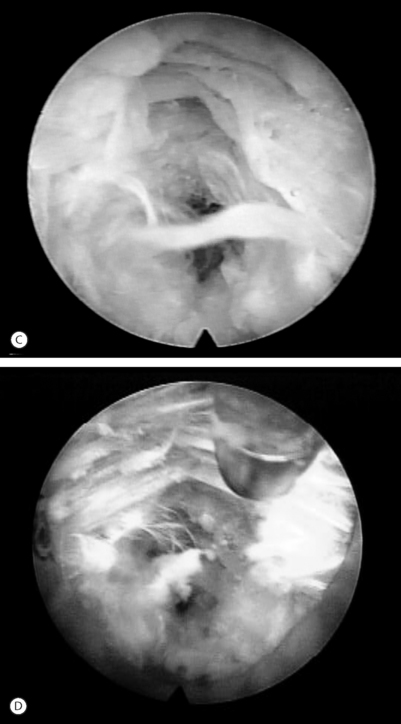

The role of intraoperative Evocative Chromo-discography™

If a vital dye is used to effect differential staining in the disc and epidural space intraoperatively, it is easier to recognize degenerative nucleus pulpolsus from normal nucleus, and the anulus and from facet capsule.4 The epidural space with its epidural vessels and fat become easy to differentiate and recognize. I trademarked evocative chromodiscography™ as an integral part of spinal endoscopy. The process of removing the indigo carmine dye-labeled nucleus was trademarked selective endoscopic discectomy™ to describe the technique (see Fig. 133.5).12

Future considerations

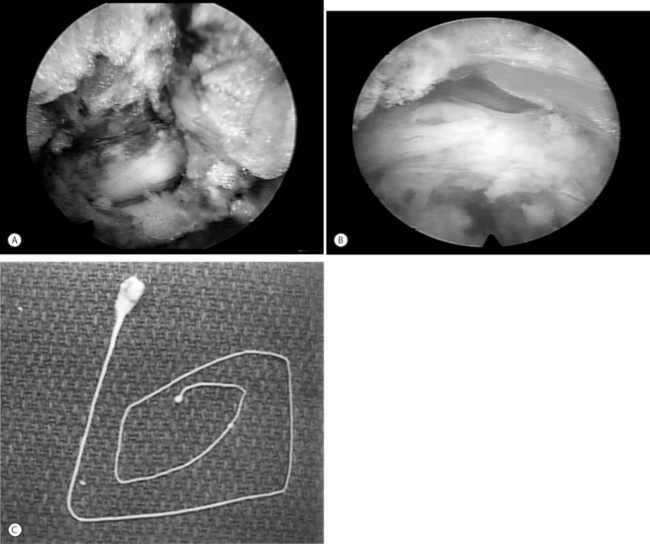

It is conceivable that the spine scope will eventually be used for all conditions where endoscopic visual inspection is desired. The authors have utilized spinal endoscopy to inspect a spinal nerve suspected to be irritated by orthopedic hardware adjacent to the pedicle, to remove suspected recurrent or residual disc herniations that do not show up on imaging studies, to decompress the lateral recess by endoscopic laser foraminoplasty, to remove osteophytes and facet cysts that cause unrelenting sciatica, and to locate painful lateral annular tears or small disc herniations not evident on physical examination or on MRI. Some of these correctable lesions are responsible for failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), especially with recurrent disc herniations and with lateral recess stenosis. The lateral ‘hidden zone’ is rarely visualized by surgeons. It has been demonstrated that, with endoscopy, it is possible to do isolated disc and annulus surgery using a visualized thermal modulation procedure (Fig. 133.8), challenging the old concept that disc surgery is merely nerve decompressive surgery. For example, discogenic pain from annular tears is currently being evaluated and correlated with the pathoanatomic conditions visualized.18,22–32

TECHNIQUE

Endoscopic spine surgery: the posterolateral approach

The current technique utilized by the authors has evolved over a 13-year period beginning in 1991 after learning arthroscopic microdiscectomy from Parviz Kambin. Previously, the authors had experience in the use of chymopapain, automated percutaneous discectomy, laser discectomy, and discography. The current technique combines the best features of each percutaneous procedure into a visualized endoscopic method that is described as selective endoscopic discectomy™, thermal discoplasty, and annuloplasty. It continues by incorporating endoscopic foraminoplasty techniques for degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine. The foraminal approach is refined further by a standardized surgical protocol that helps decrease the learning curve.

PROBLEMS AND COMPLICATIONS

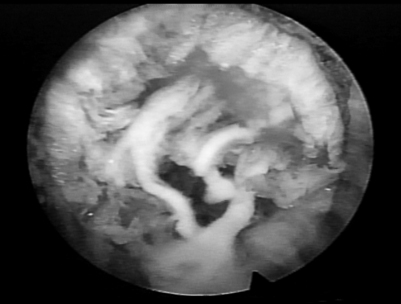

As with arthroscopic knee surgery, the risks of serious complications or nerve injury are low, about 1–3% in the authors’ experience.33 The usual risks of infection, nerve injury, dural tears, bleeding, and scar tissue formation are always present, as with any spinal surgery. Fenestration past the anterior annulus is a potential hazard, creating a bowel or vascular injury. Although this is a rare complication because the thickness of the anterior annulus will usually prevent fenestration, it must be recognized as a potential risk if the annulus is weakened or fenestrated by an anterior disc herniation. This risk is also present with the posterior approach. One limitation of the endoscopic technique is the need to use some instruments in a ‘blind’ fashion. This occurs because the size of shavers, pituitary rongeurs, and basket forceps are too large to fit into the working channel of the endoscope. Of course, their placement and use must be monitored with fluoroscopy. The cannulae are designed to protect vital structures by utilizing windows as surgical portals. Spinal nerves may be adherent to the disc and annulus, and can be extracted along with the disc or annulus by shavers or cutting instruments. In addition, the authors have identified anomalous autonomic and peripheral nerves in the foramen (furcal nerves), buried in the annular fat, that connect with the sacral plexus or the traversing nerve. These nerves are described in the medical literature and can be symptomatic but are typically small and not appreciated during open surgery. These furcal nerves are readily visualized endoscopically and probing them can produce pain in the awake patient. (Fig. 133.9). The inflammatory membrane may contain tiny nerves and blood vessels that contribute to severe discogenic pain (Fig. 133.10).

Dysesthesia, the most common postoperative complaint, occurs about 5–15% of the time, but is almost always transient. Its cause is still incompletely understood and may be related to manipulation of furcal nerves or the anulus. Another possibility is simply delayed nerve recovery as the symptoms typically occur days or weeks after surgery. Finally, this side effect may be due to irritation of the dorsal root ganglion from manipulation or postoperative bleeding. This condition cannot be completely avoided, as neuromonitoring with dermatomal SEP and continuous EMG, the most sensitive means of monitoring, has not identified intraoperative irritation as the major cause of dysesthesia.34 In some cases the symptoms can be severe and similar to complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), but usually without the skin changes that accompany CRPS. Stimulation of the dorsal root ganglion of the exiting spinal nerve can also result in dysesthesia when foraminoplasty is performed, even when the exiting nerve was clearly identified and protected during endoscopy.

The endoscopic technique, because of its approach, may be accompanied by risk for iatrogenic injury. We suspect spinal endoscopy is safer than traditional surgery, as the patient is awake and able to provide immediate input to the surgeon when pain is generated. Since the authors prefer patients to be reasonably alert, we never use propofol for ‘sedation.’ Neuromonitoring techniques can warn the surgeon of nerve irritation. About 66% of the time, there is EMG activity recorded that warns the surgeon that there is nerve irritation.34 Neuromonitoring may give the surgeon more intraoperative feedback, but in a subsequent study comparing surgical cases without neuromonitoring, it has been demonstrated to be just as safe using of dilute local anesthetic and conscious sedation. As previously stated, the patient’s ability to feel pain provides the surgeon with a safety net. Consequently, the authors only use a dilute solution of local anesthetic (0.5% Xylocaine or its equivalent) to minimize the risk of deeply anesthetizing the spinal nerve. As well, the ability of the patient to report pain during the probing component of the procedure will enable the recognition of pain generators in the spine. When there is documented postoperative improvement in nerve conduction velocities and improvement of abnormal preoperative EMGs immediately postoperatively, this is clear, objective evidence of clinical improvement.34 If a patient is not improved following surgery when electrodiagnostic studies show an improvement, it is likely due to the progression of the disease process itself.

KEY POINTS

1 Macnab I. Negative disc exploration. An analysis of the causes of nerve-root involvement in sixty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1971;53(5):891-903.

2 Yeung AT. Endoscopic spinal surgery: what future role? J Musculoskeletal Med. 2001;18(11):518-528.

3 Yeung A.T. Discography, foraminal epidurography and therapeutic foraminal injections: its role in endoscopic spine surgery. In: International 22nd course for Percutaneous Endoscopic Spinal Surgery and Complementary Techniques. 2004; Zurich, Switzerland, January 20–30.

4 Yeung AT. The role of provocative discography in endoscopic disc surgery. In: Savitz MH, Chiu J, Yeung AT, editors. The practice of minimally invasive spinal technique. AAMISMS Education LLC; 2000:231-236.

5 Yeung AT, Porter J. Minimally invasive endoscopic surgery for the treatment of lumbar discogenic pain. In: Pain management: a practical guide for clinicians. Lyon: CRC Press; 2002:1073-1078.

6 Yeung AT Endoscopic decompressive approaches to the disc. In: North American Spine Society Annual Meeting Symposium: Minimally invasive surgical treatments of spinal pathhologies: a rational approach. 2003; San Diego California, October 21–25.

7 Yeung AT, Gore SA. Evolving methodology in treating discogenic back pain by selective endoscopic discectomy (SED). J Minimally Invasive Spinal Technique. 2001;1:8-16.

8 Tsou PM, Yeung AT. Transforaminal endoscopic decompression for radiculopathy secondary to intracanal noncontained lumbar disc herniations: outcome and technique. Spine J. 2002;2(1):41-48.

9 Yeung AT, Tsou PM. Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: Surgical technique, outcome, and complications in 307 consecutive cases. Spine. 2002;27(7):722-731.

10 Savitz SI, Savitz MH, Yeung AT. Antibiotic prophylaxis for percutaneous discectomy. J Minimally Invasive Spinal Technique. 2001;1(Inaugural):49-51.

11 Yeung AT. Endoscopic access for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine. In: International Society for Minimal Intervention In Spinal Surgery, 19th course for Percutaneous Spinal Surgery and Complementary Techniques. 2001; Zurich, Switzerland, January 25–26.

12 Yeung AT, Yeung CA. Advances in endoscopic disc and spine surgery: foraminal approach. Surg Technol Int. 2003;11:253-261.

13 Osman SG, et al. Transforaminal and posterior decompressions of the lumbar spine. A comparative study of stability and intervertebral foramen area. Spine. 1997;22(15):1690-1695.

14 Yeung AT. Minimal invasive techniques in the lumbar spine: evolving methodology since 1991 (Magistral speaker). In: International 20th Jubilee course for Percutaneous Endoscopic Spinal Surgery and Complementary Techniques. 2002; Zurich, Switzerland.

15 Yeung AT. The evolution of percutaneous spinal endoscopy and discectomy: state of the art. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(4):327-332.

16 Yeung AT. Selective discectomy with the Yeung endoscopic spine system. In: Savitz MH, Chiu J, Yeung AT, editors. The practice of minimally invasive spinal technique. AAMISMS Education LLC; 2000:115-122.

17 Yeung AT. Transforaminal endoscopic selective nuclectomy and annuloplasty for chronic lumbar discogenic pain: an alternative to fusion. In: Spine Arthroplasty II Spine Arthroplasty Society 2002; Montpellier, France, May 5–8.

18 Yeung AT. Macro-and micro-anatomy of degenerative conditions of the lumbar spine (Best Paper Presentation Award). In: International Intradiscal Therapy Society 16th Annual Meeting. 2003; Chicago, Illinois, April 2–5.

19 Yeung AT. Rauschning’s anatomy for minimally invasive spine surgery. In: Spine across the sea. 2003; July 27–31.

20 Carragee EJ, et al. The rates of false-positive lumbar discography in select patients without low back symptoms. Spine. 2000;25(11):1373-1380. discussion 1381

21 Carragee EJ, et al. False-positive findings on lumbar discography. Reliability of subjective concordance assessment during provocative disc injection. Spine. 1999;24(23):2542-2547.

22 Tsou PM, Yeung AT, Yeung CA. Posterolateral transforaminal selective endoscopic discectomy and thermal annuloplasty for chronic lumbar discogenic pain. Spine J 2004;

23 Yeung AT. Arthroscopic electro-thermal surgery for discogenic low back pain: a preliminary report. In: International Intradiscal Therapy Society Annual Meeting. 1998; San Antonio, Texas.

24 Yeung AT. Classification and electro-thermal treatment of annular tears. In: American Back Society Annual Meeting. 1998; Las Vegas, Nevada, December 12.

25 Yeung AT. Annular tears: correlating discogram and endoscopic findings with electrothermal response. In: International Intradiscal Therapy Society and International Society for Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery Annual Meeting. 1999; Cambridge, England, August 1–5.

26 Yeung AT. Endoscopic thermal modulation as an alternative to fusion for discogenic pain. In: International Meeting for Advanced Spine Technologies. 1999; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, July 8–10.

27 Yeung AT. Patho-anatomy of discogenic pain. In: Minimally Invasive Spine Update. 1999; Disney Magic Cruise, Nov 5–8.

28 Yeung AT. Thermal modulation of disc pathology. In: 1st World Congress American Academy of Minimally Invasive Spinal Medicine and Surgery. 2000; Las Vegas, Nevada, Dec 7–10.

29 Yeung AT. Thermal modulation: SED versus IDET. In: 1st World Congress American Academy of Minimally Invasive Spinal Medicine and Surgery. 2000; Las Vegas, Nevada, Dec 7–10.

30 Yeung AT, et al. Intradiscal thermal therapy for discogenic low back pain. In: Savitz MH, Chiu J, Yeung AT, editors. The practice of minimally invasive spinal technique. AAMISMS Education LLC, 2000.

31 Yeung AT, Savitz MH. Treatment of multi-level lumbar disc disease by selective endoscopic discectomy and thermal annuloplasty: case report. J Minimally Invasive Spinal Technique. 2002;2(Spring):36. AAMISMS Education LLC; 200038.

32 Yeung AT, Yeung CA. Microtherapy in low back pain. In: Mayer M, editor. Minimally invasive spine surgery. New York: Springer Verlag, 2004.

33 Yeung AT, Savitz MH. Complications of percutaneous spinal surgery. In: Vacarro A, ed. Complications in adult and pediatric spine surgery. 2004.

34 Yeung AT, Porter J, Merican C. SEP as a sensory integrity check in selective endoscopic discectomy using the Yeung endoscopic spine system. In: 2nd World Congress American Academy of Minimally Invasive Spinal Medicine and Surgery. 2001; Las Vegas, Nevada, December.