Chapter 11 Endoscopic Component Separation ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

The rectus muscle can be fairly wide, up to 8 to 10 cm, and therefore the initial cut down for the balloon dissector must be performed in the lateral abdominal wall to avoid inadvertently placing the balloon in the rectus sheath.

The rectus muscle can be fairly wide, up to 8 to 10 cm, and therefore the initial cut down for the balloon dissector must be performed in the lateral abdominal wall to avoid inadvertently placing the balloon in the rectus sheath. Understanding the anatomic characteristics of the external and internal oblique muscles is critical to ensuring accurate placement of the balloon dissector when performing an endoscopic component separation. The external oblique is primarily fascialike on the lower to midabdomen and is more muscular laterally and cephalad. The internal oblique is primarily muscular except for the most medial 2 to 3 cm of fascia just before its insertion into the linea semilunaris.

Understanding the anatomic characteristics of the external and internal oblique muscles is critical to ensuring accurate placement of the balloon dissector when performing an endoscopic component separation. The external oblique is primarily fascialike on the lower to midabdomen and is more muscular laterally and cephalad. The internal oblique is primarily muscular except for the most medial 2 to 3 cm of fascia just before its insertion into the linea semilunaris.2 Preoperative Considerations

2 Anatomic Considerations

Skin Considerations

Skin Considerations

Skin ulcerations and peristomal excoriations are carefully prepared preoperatively to maximize healing potential. Because skin flaps are not raised in this technique, skin preservation is very important.

Skin ulcerations and peristomal excoriations are carefully prepared preoperatively to maximize healing potential. Because skin flaps are not raised in this technique, skin preservation is very important. The primary advantage of an endoscopic component separation is the elimination of lipocutaneous skin flaps. This reduces wound infections and flap ischemia. In cases where excess skin must be resected or skin flaps will be necessary to mobilize the skin to the midline, the endoscopic component separation should not be used. In these cases an open component separation or concomitant panniculectomy is performed as described in other chapters.

The primary advantage of an endoscopic component separation is the elimination of lipocutaneous skin flaps. This reduces wound infections and flap ischemia. In cases where excess skin must be resected or skin flaps will be necessary to mobilize the skin to the midline, the endoscopic component separation should not be used. In these cases an open component separation or concomitant panniculectomy is performed as described in other chapters. Musculofascial Considerations

Musculofascial Considerations

Ideal characteristics for an endoscopic component separation include a relatively wide, well-preserved rectus muscle. With a wide rectus muscle, a large mesh typically can be placed in the retrorectus position as an underlay (as described in Chapter 5 without a skin flap).

Ideal characteristics for an endoscopic component separation include a relatively wide, well-preserved rectus muscle. With a wide rectus muscle, a large mesh typically can be placed in the retrorectus position as an underlay (as described in Chapter 5 without a skin flap). Component separation techniques have limitations. Large defects, >20 cm in width, and multiple recurrent hernias with fixed noncompliant abdominal walls often cannot be medialized with this technique. In addition, patients with transverse incisions should not be approached with an endoscopic technique.

Component separation techniques have limitations. Large defects, >20 cm in width, and multiple recurrent hernias with fixed noncompliant abdominal walls often cannot be medialized with this technique. In addition, patients with transverse incisions should not be approached with an endoscopic technique. Reconstructive Considerations

Reconstructive Considerations

3 Operative Steps

1 Equipment

Equipment needs include a10-mm, 30-degree laparoscope; bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector (Covidien, Norwalk, CT); 30-mL balloon-tipped trocar (Covidien, Norwalk, CT); laparoscopic trocars; and an ultrasonic dissector or LigaSure™ device (Covidien, Norwalk, CT) (Fig. 11-1).

Equipment needs include a10-mm, 30-degree laparoscope; bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector (Covidien, Norwalk, CT); 30-mL balloon-tipped trocar (Covidien, Norwalk, CT); laparoscopic trocars; and an ultrasonic dissector or LigaSure™ device (Covidien, Norwalk, CT) (Fig. 11-1). Patients receive appropriate preoperative antibiotics and invasive monitoring as needed, and epidural catheters are routinely placed for postoperative pain control.

Patients receive appropriate preoperative antibiotics and invasive monitoring as needed, and epidural catheters are routinely placed for postoperative pain control. Trocar Strategy

Trocar Strategy

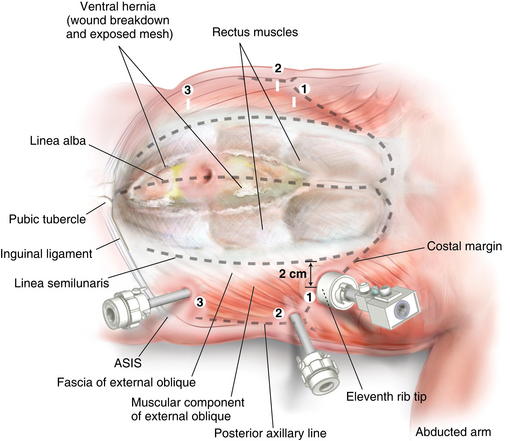

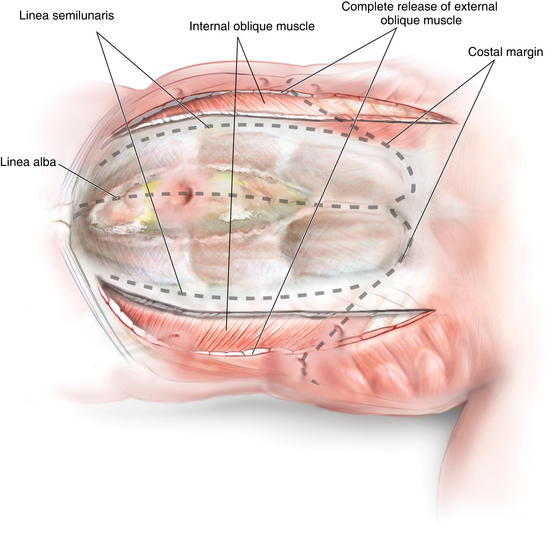

Figure 11-2 shows trocar positioning, with lines showing the linea semilunaris, external oblique fascia, and costal margin

Figure 11-2 shows trocar positioning, with lines showing the linea semilunaris, external oblique fascia, and costal margin Endoscopic Component Separation Operative Steps

Endoscopic Component Separation Operative Steps

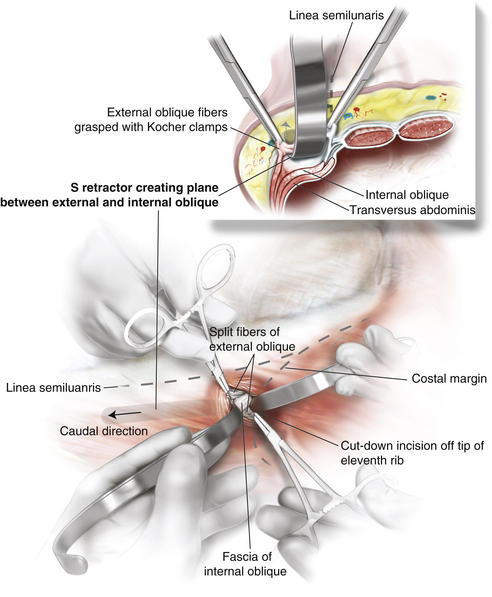

A cut-down incision is performed off the tip of the eleventh rib. It is critical that this incision is made lateral to the linea semilunaris to avoid placing the balloon in the rectus sheath. This port should be placed lateral enough to allow space between the linea semilunaris and the trocar, enabling complete cephalad dissection. In my opinion, this is the most important step in the operation, and the anatomy must be clearly identified. Therefore, in obese patients I extend this incision to the appropriate size to permit clear identification of the fibers of the external oblique. The subcutaneous tissue and Scarpa fascia are bluntly separated, and the external oblique is grasped with Kocher clamps.

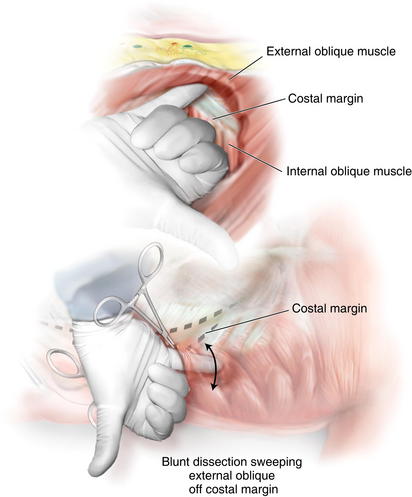

A cut-down incision is performed off the tip of the eleventh rib. It is critical that this incision is made lateral to the linea semilunaris to avoid placing the balloon in the rectus sheath. This port should be placed lateral enough to allow space between the linea semilunaris and the trocar, enabling complete cephalad dissection. In my opinion, this is the most important step in the operation, and the anatomy must be clearly identified. Therefore, in obese patients I extend this incision to the appropriate size to permit clear identification of the fibers of the external oblique. The subcutaneous tissue and Scarpa fascia are bluntly separated, and the external oblique is grasped with Kocher clamps. Depending on how far lateral you have performed your cut down, the external oblique can be only fascia or fascia and muscle. It is important to confirm this anatomy, to avoid cutting too deep into the internal oblique. The external oblique fibers are split and bluntly separated. An S retractor gently creates the plane underneath the external oblique and above the internal oblique heading in a caudal direction (Fig. 11-3).

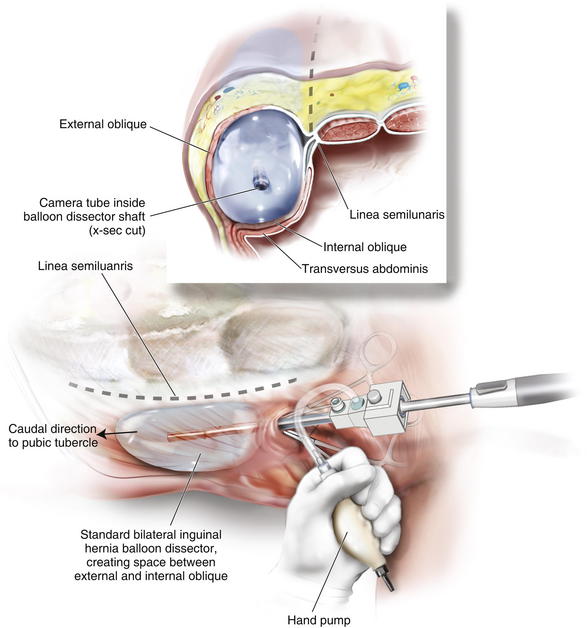

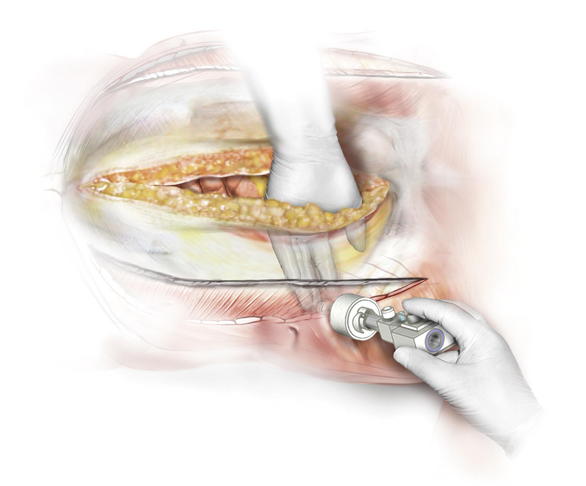

Depending on how far lateral you have performed your cut down, the external oblique can be only fascia or fascia and muscle. It is important to confirm this anatomy, to avoid cutting too deep into the internal oblique. The external oblique fibers are split and bluntly separated. An S retractor gently creates the plane underneath the external oblique and above the internal oblique heading in a caudal direction (Fig. 11-3). A standard bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector is placed underneath the external oblique and passed inferiorly to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 11-4). This balloon should be guided laterally to avoid injuring the linea semilunaris. If prior transverse incisions are encountered, the balloon might not be able to traverse the scar tissue and should be aborted and the intermuscular space created under direct vision.

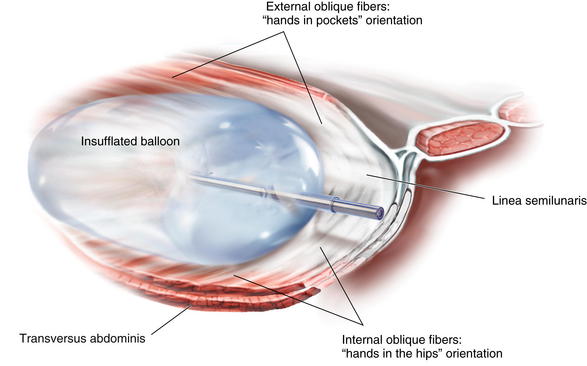

A standard bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector is placed underneath the external oblique and passed inferiorly to the pubic tubercle (Fig. 11-4). This balloon should be guided laterally to avoid injuring the linea semilunaris. If prior transverse incisions are encountered, the balloon might not be able to traverse the scar tissue and should be aborted and the intermuscular space created under direct vision. The balloon is insufflated under direct vision, and the orientation of the external oblique fibers (“hands in pockets”), internal oblique fibers (“hands on the hips”), and the linea semilunaris are identified (Fig. 11-5).

The balloon is insufflated under direct vision, and the orientation of the external oblique fibers (“hands in pockets”), internal oblique fibers (“hands on the hips”), and the linea semilunaris are identified (Fig. 11-5). The shape of the standard bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector does not permit cephalad dissection of the external oblique off the costal margin. Therefore, the balloon is removed, and a finger is placed in the intermuscular space, and the dissection is bluntly carried out over the costal margin using a sweeping motion (Fig. 11-6). If this space is not created at this point, the dissection planes can be confusing laparoscopically and may result in a technical error. Remember the external oblique inserts 5 to 7 cm above the costal margin and should be cleared off the costal margin to permit the muscles to slide medially.

The shape of the standard bilateral inguinal hernia balloon dissector does not permit cephalad dissection of the external oblique off the costal margin. Therefore, the balloon is removed, and a finger is placed in the intermuscular space, and the dissection is bluntly carried out over the costal margin using a sweeping motion (Fig. 11-6). If this space is not created at this point, the dissection planes can be confusing laparoscopically and may result in a technical error. Remember the external oblique inserts 5 to 7 cm above the costal margin and should be cleared off the costal margin to permit the muscles to slide medially. A balloon tipped trocar is secured in the space to prevent air leakage. One should avoid the use of a triangular shaped structural balloon at this point because it can result in obliteration of the dissection space. Insufflation pressures of 10 to 12 mm Hg are used.

A balloon tipped trocar is secured in the space to prevent air leakage. One should avoid the use of a triangular shaped structural balloon at this point because it can result in obliteration of the dissection space. Insufflation pressures of 10 to 12 mm Hg are used. The inferior space can be bluntly created with a 30-degree, 10-mm laparoscope to complete the dissection of the intermuscular space to the posterior axillary line and inguinal ligament.

The inferior space can be bluntly created with a 30-degree, 10-mm laparoscope to complete the dissection of the intermuscular space to the posterior axillary line and inguinal ligament. The second port is placed in the posterior axillary line. This port is placed as far laterally as possible to provide the appropriate angle to release the external oblique, 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris.

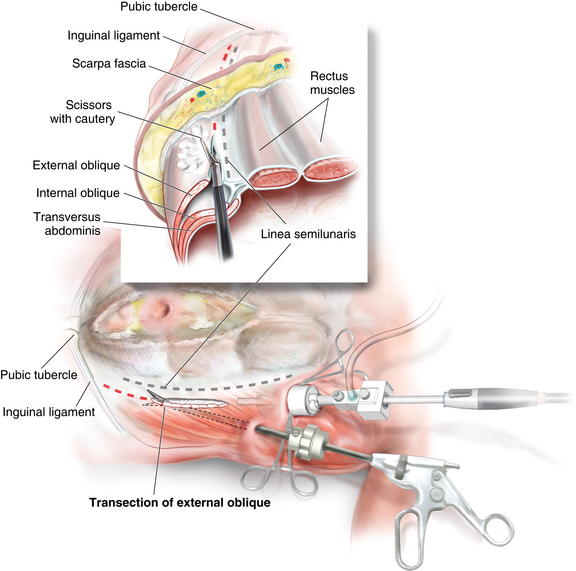

The second port is placed in the posterior axillary line. This port is placed as far laterally as possible to provide the appropriate angle to release the external oblique, 2 cm lateral to the linea semilunaris. Using scissors with cautery, in the posterior axillary port, and the camera in the cut-down port, the external oblique is incised from as cephalad as possible, to the inguinal ligament/ pubic tubercle (Fig. 11-7). Great care should be taken to complete the release lateral to the linea semilunaris.

Using scissors with cautery, in the posterior axillary port, and the camera in the cut-down port, the external oblique is incised from as cephalad as possible, to the inguinal ligament/ pubic tubercle (Fig. 11-7). Great care should be taken to complete the release lateral to the linea semilunaris. Extra release can be achieved by continuing the dissection superficially through Scarpa fascia. The majority of the blood supply runs superficial to this layer and won’t be disturbed.

Extra release can be achieved by continuing the dissection superficially through Scarpa fascia. The majority of the blood supply runs superficial to this layer and won’t be disturbed. The third port is placed through the released external oblique in the lower abdomen. This port is placed medial to the original cut-down port in the line that the external oblique will be transected when going over the costal margin. This orientation is important because the cephalad portion of the dissection can be challenging as it is performed in a reverse camera orientation.

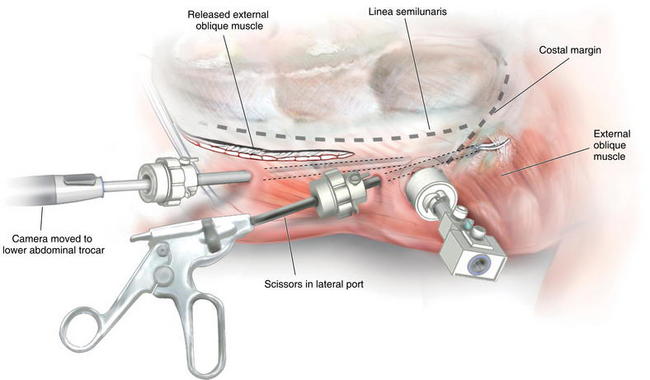

The third port is placed through the released external oblique in the lower abdomen. This port is placed medial to the original cut-down port in the line that the external oblique will be transected when going over the costal margin. This orientation is important because the cephalad portion of the dissection can be challenging as it is performed in a reverse camera orientation. The camera is then placed in the lower abdominal trocar and the scissors are placed in the lateral port, and the cephalad dissection is completed separating the external oblique off the costal margin (Fig. 11-8). The external oblique is carefully separated off the costal margin to provide a clear plane and trajectory when transecting the external oblique. This avoids releasing the linea semilunaris or dissecting underneath the costal margin.

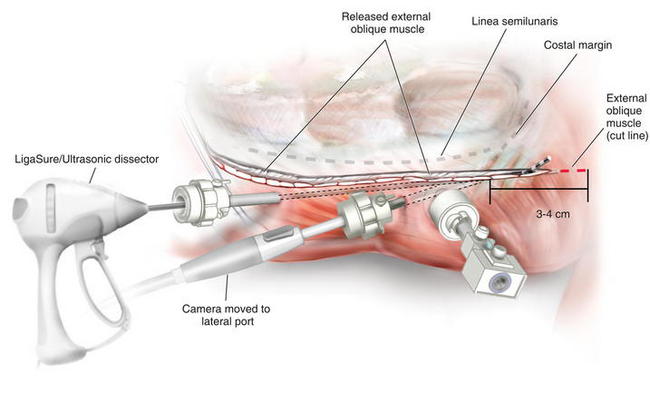

The camera is then placed in the lower abdominal trocar and the scissors are placed in the lateral port, and the cephalad dissection is completed separating the external oblique off the costal margin (Fig. 11-8). The external oblique is carefully separated off the costal margin to provide a clear plane and trajectory when transecting the external oblique. This avoids releasing the linea semilunaris or dissecting underneath the costal margin. Once the dissection of the external oblique is completed, the camera is positioned in the lateral port and the LigaSure™ ultrasonic dissector is placed in the inferior port (Fig. 11-9). Since the external oblique is fairly muscular at the cephalad portion, I prefer to use LigaSure™, as simple cautery can result in troublesome bleeding.

Once the dissection of the external oblique is completed, the camera is positioned in the lateral port and the LigaSure™ ultrasonic dissector is placed in the inferior port (Fig. 11-9). Since the external oblique is fairly muscular at the cephalad portion, I prefer to use LigaSure™, as simple cautery can result in troublesome bleeding. The external oblique is transected several centimeters above the costal margin (Fig. 11-10). The exact cephalad extent of the transection of the external oblique is variable, but it should be at least 5 cm above the superior extent of the hernia defect, and likely, at least 3 to 4 cm above the costal margin.

The external oblique is transected several centimeters above the costal margin (Fig. 11-10). The exact cephalad extent of the transection of the external oblique is variable, but it should be at least 5 cm above the superior extent of the hernia defect, and likely, at least 3 to 4 cm above the costal margin. Mesh Placement

Mesh Placement

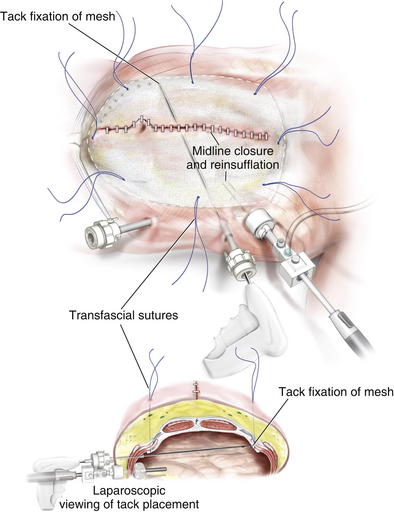

In general, mesh should be placed under appropriate physiologic tension, using transfascial fixation sutures to aid in medialization of the rectus muscles. These sutures allow the forces of the abdominal closure to be redistributed to lateral abdominal wall. If the mesh is placed in a completely tension-free manner, and the fascia is reapproximated in the midline, the mesh will buckle, and this likely leads to seroma formation, poor integration, and mesh sepsis.

In general, mesh should be placed under appropriate physiologic tension, using transfascial fixation sutures to aid in medialization of the rectus muscles. These sutures allow the forces of the abdominal closure to be redistributed to lateral abdominal wall. If the mesh is placed in a completely tension-free manner, and the fascia is reapproximated in the midline, the mesh will buckle, and this likely leads to seroma formation, poor integration, and mesh sepsis. Retrorectus Placement

Retrorectus Placement

My preferred space for mesh placement is in the posterior rectus space. By using this technique as described in Chapter 5 skin flaps are not necessary for wide mesh overlap. Drains are routinely placed above the mesh and below the rectus muscle. Although some authors describe continuing the dissection through the linea semilunaris into the lateral abdominal plane during a retrorectus repair, this should be avoided if a component separation has been performed. If the external oblique is released and then the transversus abdominis is intentionally or unintentionally released, the lateral abdominal wall is only supported by the internal oblique, which likely will result in at least a bulge if not a hernia. Therefore, if the rectus muscle seems too narrow to place a wide enough piece of mesh, the surgeon has several alternative options. A standard open component separation can be performed, allowing large skin flaps and easier mesh placement

My preferred space for mesh placement is in the posterior rectus space. By using this technique as described in Chapter 5 skin flaps are not necessary for wide mesh overlap. Drains are routinely placed above the mesh and below the rectus muscle. Although some authors describe continuing the dissection through the linea semilunaris into the lateral abdominal plane during a retrorectus repair, this should be avoided if a component separation has been performed. If the external oblique is released and then the transversus abdominis is intentionally or unintentionally released, the lateral abdominal wall is only supported by the internal oblique, which likely will result in at least a bulge if not a hernia. Therefore, if the rectus muscle seems too narrow to place a wide enough piece of mesh, the surgeon has several alternative options. A standard open component separation can be performed, allowing large skin flaps and easier mesh placement Intraperitoneal Placement

Intraperitoneal Placement

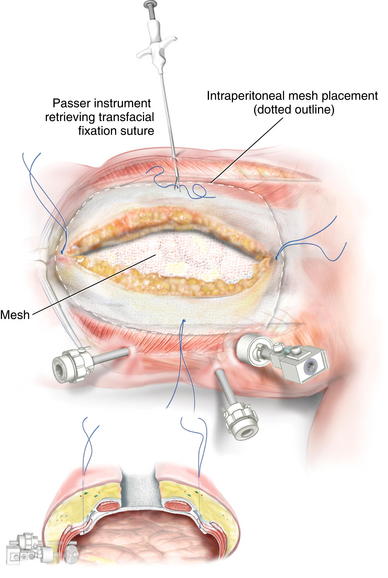

Placing a large piece of mesh in the intraperitoneal position without a skin flap is technically challenging. Alternatively, laparoscopic visualization can be used to fixate the mesh. In this approach, the abdominal portion of the procedure can be completed in an open fashion. Before closing the midline incision, the mesh can be placed intraperitoneally and secured with several transfascial fixation sutures (Fig. 11-11). Several laparoscopic ports can be placed in the lateral abdominal wall under direct visualization. The midline incision is then closed to allow for insufflation of the peritoneal cavity. The mesh can then be secured using various laparoscopic fixation devices, including tackers or transfascial sutures (Figs. 11-12 and 11-13).

Placing a large piece of mesh in the intraperitoneal position without a skin flap is technically challenging. Alternatively, laparoscopic visualization can be used to fixate the mesh. In this approach, the abdominal portion of the procedure can be completed in an open fashion. Before closing the midline incision, the mesh can be placed intraperitoneally and secured with several transfascial fixation sutures (Fig. 11-11). Several laparoscopic ports can be placed in the lateral abdominal wall under direct visualization. The midline incision is then closed to allow for insufflation of the peritoneal cavity. The mesh can then be secured using various laparoscopic fixation devices, including tackers or transfascial sutures (Figs. 11-12 and 11-13).4 Postoperative Care

Not all defects can be closed with a component separation. If excessive tension is necessary to reapproximate the midline fascia, a bridging type repair is indicated. Careful monitoring of hemodynamic physiology and changes in airway pressure are undertaken. All patients undergoing complex abdominal wall reconstructions remain intubated overnight if there is a rise of greater than 5 mm Hg in plateau airway pressures after fascial closure.

Not all defects can be closed with a component separation. If excessive tension is necessary to reapproximate the midline fascia, a bridging type repair is indicated. Careful monitoring of hemodynamic physiology and changes in airway pressure are undertaken. All patients undergoing complex abdominal wall reconstructions remain intubated overnight if there is a rise of greater than 5 mm Hg in plateau airway pressures after fascial closure. It should be noted that the full effect of a component separation is typically not seen until 24 to 48 hours later, and defects can often be closed under moderate tension and allow the abdominal wall to completely expand.

It should be noted that the full effect of a component separation is typically not seen until 24 to 48 hours later, and defects can often be closed under moderate tension and allow the abdominal wall to completely expand. Epidural catheters are maintained until patients are tolerating a diet and have full return of bowel function.

Epidural catheters are maintained until patients are tolerating a diet and have full return of bowel function. Diets are not advanced until patients have return of bowel function. While early postoperative feeding has shown promise in other fields of surgery, early postoperative retching and vomiting can lead to disruption of the surgical repair in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Routine nasogastric tube decompression is avoided.

Diets are not advanced until patients have return of bowel function. While early postoperative feeding has shown promise in other fields of surgery, early postoperative retching and vomiting can lead to disruption of the surgical repair in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Routine nasogastric tube decompression is avoided.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

Medial advancement is difficult to achieve with defects at the xiphoid and suprapubic region of the abdominal wall. These should be avoided early in one’s experience.

Medial advancement is difficult to achieve with defects at the xiphoid and suprapubic region of the abdominal wall. These should be avoided early in one’s experience. Large defects, >20 cm, and noncompliant fixed abdominal wall defects often cannot be medialized to completely reconstruct the linea alba.

Large defects, >20 cm, and noncompliant fixed abdominal wall defects often cannot be medialized to completely reconstruct the linea alba. Realistic expectations for patients, families, and surgeons as to the severity of the operation, including risks, and the ability to reconstruct a normal abdominal wall are critical to the success of this procedure.

Realistic expectations for patients, families, and surgeons as to the severity of the operation, including risks, and the ability to reconstruct a normal abdominal wall are critical to the success of this procedure. Endoscopic component separation is ideal in circumstances where a stoma is present. If the stoma is through the rectus muscle, a component separation can be performed endoscopically without undermining the skin around the stoma and risking peristomal skin necrosis and a floating stoma.

Endoscopic component separation is ideal in circumstances where a stoma is present. If the stoma is through the rectus muscle, a component separation can be performed endoscopically without undermining the skin around the stoma and risking peristomal skin necrosis and a floating stoma. Component separation should be performed bilaterally in most cases to redistribute the tension symmetrically during closure.

Component separation should be performed bilaterally in most cases to redistribute the tension symmetrically during closure.Harth K.C., Rosen M.J. Endoscopic versus open component separation in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2010 Mar;199(3):342-346. discussion 346–347

Rosen M.J., Fatima J., Sarr M.G. Repair of abdominal wall hernias with restoration of abdominal wall function. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 Jan;14(1):175-185.

Rosen M.J., Jin J., McGee M., Marks J., Ponsky J. Laparoscopic component separation in the single stage treatment of infected abdominal wall prosthetic removal. Hernia. 2007 Oct;11(5):435-440.

Rosen M.J., Reynolds H.L., Champagne B., Delaney C.P. A novel approach for the simultaneous repair of large midline incisional and parastomal hernias with biological mesh and retrorectus reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2010 Mar;199(3):416-420. discussion 420–421

Rosen M.J., Williams C., Jin J., McGee M., Marks J., Ponsky J. Laparoscopic versus open component separation: A comparative analysis in a porcine model. Am J Surg. 2007 Sep;194(3):385-389.