CHAPTER 25 Endoscopic browlift with internal fixation

Physical evaluation

1. The sequelae of senescence in the upper third of the face range from subtle to dramatic. Glabellar and forehead rhytids, eyebrow ptosis/laxity, and forehead lengthening may appear in a range of severity. It is paramount to evaluate each of these factors in determining the best operative approach for the patient.

2. The artist’s canon of equal facial thirds. Symmetry of the facial thirds is considered attractive by most cultural standards. Conversely, an elongated upper facial third is deemed a sign of senescence. Evaluation of the hairline and the quality of the hair may also allow the clinician to determine patients at risk for visible scars and possible alopecia from scalp dissection.

3. The position of the eyebrow arch. In the ideal representation of the eyebrow, the medial brow is located at the level of the supraorbital rim and begins at a line perpendicular to the alar base. The arch then ascends slightly to the apex of the arch, located at a perpendicular line to the lateral limbus (at approximately the junction of the medial two-thirds and lateral one-third of the brow). The arch is slightly above the supraorbital rim in females and at the level of the supraorbital rim in males. The lateral extent of the brow is at a line extending from the alar base and the lateral canthus.

4. Further evaluation of the brow should include evaluation of brow symmetry. In cases of asymmetry, variable fixation of the two sides may result in a more even appearance to the brow arch. Discussion of preoperative asymmetry with the patient is important preoperatively and may minimize patient dissatisfaction if perfect symmetry is not achieved.

5. Eyelid ptosis. The etiology of the ptosis must include the differentiation of dermatochalasis versus true brow ptosis. In order to discern this difference, the examiner may have the patient tightly close their lids, then slowly open their eyes until they can see the examiner. This, in effect, negates the effect of the frontalis on the brow elevation. As the patient continues to open their eyes, the frontalis naturally compensates the brow position. Another method to deactivate the frontalis is to have the patient smile. Manual elevation of the brow to the desired level of fixation may also be utilized in order to assess the involvement of the lid in ptosis.

6. Evaluation of forehead rhytids. Transverse forehead rhytids result from continued frontalis contraction compensating for the lowered brow position. As brow descent increases, forehead rhytids become more evident.

7. Evaluation of glabellar rhytids. Both transverse and vertical glabellar rhytids occur as a result of brow descent and glabellar muscular activity. Concomitant with this may be displacement of the medial brow below the level of the supraorbital rim.

Anatomy

The basis of rhytids in the forehead and brow are directly translated into the frontalis and glabellar musculature. The frontalis originates and is contiguous with the galeal fascia of the scalp. It extends inferiorly and becomes more superficial, investing into the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the brow. Contraction of the frontalis results in a cranial force vector, thus elevating the brow and creating transverse forehead rhytids. Cephalic translation of the forehead and brow is limited by muscular and periosteal anchors. Laterally, the frontalis terminates at the superior temporal line. This tightly adherent confluence of superficial temporal fascia, galea, temporalis fascia and periosteum has been coined the temporal zone of fixation and is one regulator of cephalic translation (Knize, 1996). The orbital suspensory ligament also limits translation by indirectly attaching the lateral eyebrow skin to the lateral orbital rim at the level of the zygomaticofrontal suture (Knize, 1996). The arcus marginalis located across the supraorbital rim also limits cephalic translation of the brow. If these structures are not adequately released intraoperatively, optimal brow positioning may not be achieved.

Technical steps

The operation is performed with the patient in supine positioning, either with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. Prior to local infiltration, five radial port incisions are marked perpendicular to the hairline (Fig. 25.1). The midline incision is marked approximately 0.5 cm behind the hairline. The next set of incisions are marked as the vector of eyebrow elevation. These markings are 6.5 cm to 7 cm lateral to the midline marking and approximately 1.5 cm to 2 cm behind the hairline. The final pair of markings are approximately 3 cm lateral to the “vector” markings. All of the incisions are typically 1.2 to 1.5 cm in length, but may be slightly extended in males or in patients with thicker skin. Following marking, the non-hair-bearing forehead region is infiltrated with lidocaine 1% with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine, paying particular attention to the supraorbital ridge, glabella, and lateral temporal regions. The hair-bearing scalp is then infiltrated with lidocaine 1% with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine to minimize the possibility of postoperative alopecia.

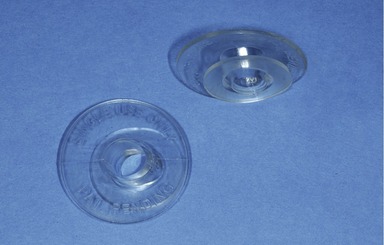

The lateral temporal ports are incised first and carefully dissected to the level of the deep temporal fascia. If the deep temporal fascia is not visualized and instead the dissection is performed in the superficial or intermediate temporal fascia, there will be inadequate visualization laterally, thus increasing the risk of injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve. The remainder of the port incisions are made and carried to the subperiosteal level. Endoscopic assist devices (Applied Medical Technology, Cleveland OH) are inserted into the port sites in order to facilitate a clean insertion of the endoscopic camera and to keep hair out of the port sites (Fig. 25.2).

Endoscopic dissection initially proceeds rapidly in the subperiosteal plane to the level of the supraorbital rim. Dissection is then extended laterally to the level of the lateral orbital rim and subsequently to the zygomatic arch (Fig. 25.3). Lateral dissection in the temporal region is performed in a blunt sweeping fashion in order to separate the superficial and deep temporal fascias. Careful dissection in the temporal region reveals both the sentinel vein and the zygomaticotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve. The sentinel vein may be dissected from its investing fascia and cauterized if necessary, being mindful of the proximity of the temporal branch of the facial nerve. Once the lateral supraorbital rim is exposed, the periosteum and the arcus marginalis are released from lateral to medial. The periosteum is preserved in the glabellar region unless preoperatively it was discerned that the medial brow is positioned low. Preservation of the medial periosteum will help prevent excessive elevation of the medial brow. Care is taken when releasing the periosteum at the level of the supraorbital nerve, as excessive traction on the nerve is unwarranted and may lead to postoperative pain or excessive neuropraxia.

The glabellar musculature (corrugator supercilli, depressor supercilli, and procerus) are then resected. The senior author’s technique includes total removal of the musculature as completely as possible. During dissection of the corrugators, the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are identified and preserved, leaving the nerves in a “skeletonized” fashion (Fig. 25.4). Often, there is a communicating vein located deep to the corrugator and between the supraorbital and supratrochlear veins. This may be cauterized as necessary. Once the muscles have been adequately resected, the subcutaneous fat is visualized. The total resection of the glabellar musculature ensures that the vertical and transverse rhytids of the glabella will be eliminated with minimal chance of resultant muscular hypertrophy. Other described techniques describe subtotal muscular resection, thus weakening but not eliminating muscular activity.

Fig. 25.4 Resection of the corrugator supercilli. Note the skeletonized appearance of the supraorbital nerve.

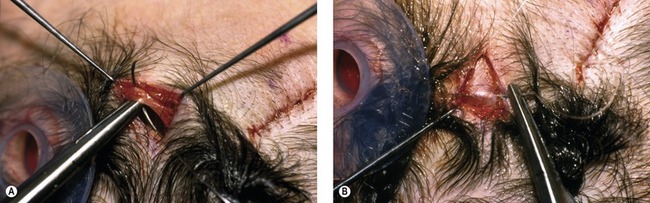

Once complete mobilization of the brow has been performed and the glabellar musculature resected, the endoscopic assist devices are removed and fixation of the brow is performed. Fixation in most instances is performed via suture fascial suspension (Fig. 25.5). At the lateral incision, a 3-0 polydioxanone suture is passed from the caudal end of the incision at the level of the superficial temporal fascia to the cephalic deep temporal fascia. This, in effect, attaches the superficial temporal fascia to the deep temporal fascia, allowing for traction of the brow without tension on the skin or superficial layers. In instances that brow arch position needs to be significantly altered, brow fixation using bone tunneling through the intermediate lateral incision may be employed. Bone tunneling is accomplished using a 1.1 mm hole burr with a safety guard at a maximum length of 4 mm. Two 45 degrees opposing burr holes are made approximately 3–4 mm apart. A 3-0 polydioxanone suture is used for the anchoring. Following fixation, a DTLS-Surgical Drainage System closed suction drain (Porex Surgical Inc., College Park, Georgia) is inserted into the lateral incision and passed across the length of the forehead. The galea and periosteum are repaired with 5-0 Monocryl and the skin is repaired with 5-0 catgut.

Fig. 25.5 Lateral fixation sutures. A, The 3-0 PDS suture is being passed through the fascia at the anterocaudal portion of the lateral-most incision. B, After the skin of the port site is pulled posterolaterally to the appropriate vector and level of brow position, the suture is passed through the deep temporal fascia.

Other methods of fixation may be employed, including percutaneous screws, absorbable fixation devices (Endotine, Coapt Systems Inc., Palo Alto, CA), non-absorbable fixation devices such as Mitek anchors or two-hole plates, fibrin glue sealant, among many others. The disadvantages of the absorbable plates and subcutaneous screws are the potential palpability of the product, possible need for removal in the instance of the Mitek fixation, and cost of the devices. Percutaneous screw fixation has the advantage of possible adjustability of the brow positioning in the immediate postoperative period. Potential disadvantages of percutaneous screw fixation include cost of the screw, greater chance for infection, and increased potential for postoperative alopecia (Fig. 25.6).

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Comprehensive preoperative examination is paramount to determine the type of resection and elevation needed.

• On the lateral-most radial incision, careful dissection to the level of the deep temporal fascia will avoid inadequate visualization laterally.

• Use of endoscopic assist devices allow easy passage of the endoscope, endoscopic instruments, and minimize introduction of hair into the wound.

• Preservation of the central portion of the periosteum will help avoid medial eyebrow elevation.

• Adequate release of the brow suspensory ligaments will allow brow elevation laterally.

Pitfalls

• Limited lateral visualization is likely due to dissection at the level of the superficial or intermediate temporal fascia and increases the risk of temporal branch of facial nerve injury.

• Brow asymmetry present preoperatively may not be corrected without the use of differential eyebrow elevation and fixation.

• Inadequate glabellar muscular resection will increase the chances of dimpling of the forehead skin and persistence of glabellar rhytids.

• Excessive brow elevation is due to excessive medial dissection and aggressive repositioning techniques.

• Undercorrection of the brow may be due to inadequate release of the arcus marginalis, orbital retaining ligaments and poor fixation.

Summary of steps

1. The operation is performed with the patient in supine positioning, either with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia.

2. Five radial port incisions are made perpendicular to the hairline. The midline incision is 0.5 cm behind the hairline. Lateral incisions are marked 6.5 to 7 cm lateral to midline and 1 cm behind the hairline. The lateral temporal incisions are then marked 3 cm lateral to the lateral incisions. All incisions are typically 1.2 to 1.5 cm in length, but may be extended in males or in patients with thicker skin.

3. The non-hair-bearing forehead region, supraorbital ridge, glabella, and lateral temporal regions are infiltrated with lidocaine 1% with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine. The hair-bearing scalp is infiltrated with lidocaine 1% with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine to minimize postoperative alopecia.

4. Lateral temporal ports are incised and meticulously dissected to the level of the deep temporal fascia.

5. The remainder of the port incisions are made and dissected to the subperiosteal level.

6. Endoscopic assist devices are inserted into the port sites.

7. Endoscopic dissection is in the subperiosteal plane to the level of the supraorbital rim. Dissection is extended laterally to the level of the lateral orbital rim and to the zygomatic arch.

8. Lateral dissection in the temporal region is performed in a blunt sweeping fashion in order to separate the superficial and deep temporal fascias.

9. Dissection in the temporal region reveals both the sentinel vein and the zygomaticotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve. The sentinel vein may be dissected from its investing fascia and cauterized if necessary, being mindful of the proximity of the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

10. The periosteum and the arcus marginalis are released from lateral to medial. The periosteum is preserved in the glabellar region unless preoperatively it was discerned that the medial brow is positioned low.

11. The glabellar musculature (corrugator supercilli, depressor supercilli, and procerus) are then resected as completely as possible.

12. The supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are identified and preserved during muscular removal, leaving the nerves in a “skeletonized” fashion.

13. Temporal fat harvest is performed using a sharp curved periosteal elevator to make a small incision in the deep temporal fascia above the medial zygomatic arch. A small piece of temporal fat is harvested through this incision.

14. The temporal fat is tailored to size and placed in the glabellar space, eliminating the depression in the overlying skin.

15. Fixation is performed via suture fascial suspension. At the lateral incision, a 3-0 polydioxanone suture is passed from the caudal end of the incision at the level of the superficial temporal fascia to the cephalic deep temporal fascia.

16. A closed suction drain is inserted into the lateral incision and passed across the length of the forehead.

17. The galea and periosteum are repaired with 5-0 Monocryl and the skin is repaired with 5-0 catgut.

Behmand RA, Guyuron B. Endoscopic forehead rejuvenation: II. Long-term results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(4):1137–1143.

Berkowitz RL, Jacobs DI, Gorman PJ. Brow fixation with the Endotine forehead device in endoscopic brow lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6):1761–1767.

Chiu ES, Baker DC. Endoscopic brow lift: a retrospective review of 628 consecutive cases over 5 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(2):628–633.

DeCordier BC, de la Torre JI, Al-Hakeem MS, et al. Endoscopic forehead lift: review of technique, cases, and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(6):1558–1568.

Guyuron B, Rose K. Harvesting fat from the infratemporal fossa. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:245.

Guyuron B. Endoscopic forehead rejuvenation: I. Limitations, flaws, and rewards. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(4):1121–1133.

Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1321–1333.

Knize DM. Endoscopic brow lift: a retrospective review of 628 consecutive patients over 5 years. Discussion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(2):634–635.

McKinney P, Sweis I. An accurate technique for fixation in endoscopic brow lift: a 5 year follow up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1808–1810.

Michelow BJ, Guyuron B. Refinements in endoscopic forehead rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:154–160.

Paul M. The evolution of the brow lift in aesthetic plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1409–1424.

Rohrich RJ, Beran SJ. Evolving fixation methods in endoscopically assisted forehead rejuvenation: controversies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(6):1575–1582.

Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, et al. Anatomy of the frontal branch of the facial nerve: the significance of the temporal fat pad. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(2):265–271.

Vasconez LO. Endoscopic forehead lift: an operative technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(7):1158–1159.