Chapter 35 Endometriosis and adenomyosis

ENDOMETRIOSIS

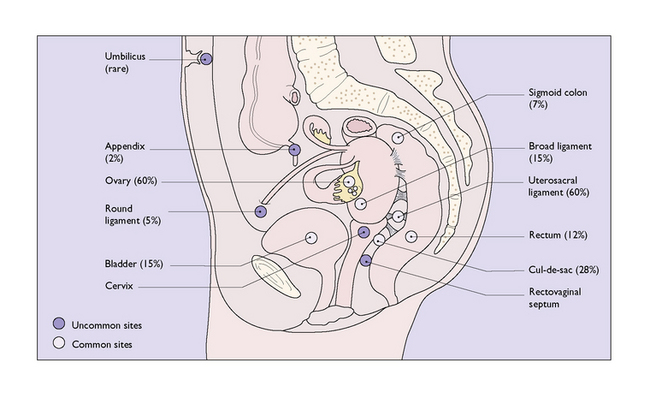

Endometriosis denotes presence of functioning endometrial tissue in an abnormal location, in other words, outside the uterus (Box 35.1). The locations and the approximate chance of the lesion affecting the organ or structure are shown in Figure 35.1.

Box 35.1 Endometriosis

| What is it? | Functioning endometrial tissue which is outside the uterus, most commonly found on the uterosacral ligament and ovary |

| Aetiology |

Pathology

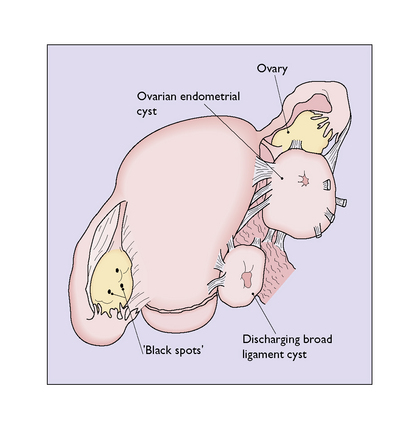

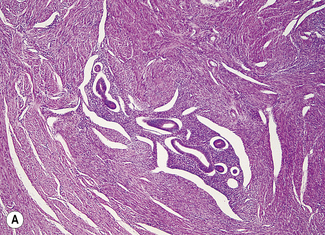

Rupture or leakage of material from even small cysts is not uncommon. The released inspissated blood is very irritating, with the result that multiple adhesions surround the cysts. The ectopic endometrium and stromal cells also tend to infiltrate adjacent tissues, leading to more pelvic adhesions and fixation (Fig. 35.2). If an ovarian cyst is found which looks like an endometrioma, but there are no adhesions, the diagnosis is unlikely to be endometriosis.

Diagnosis

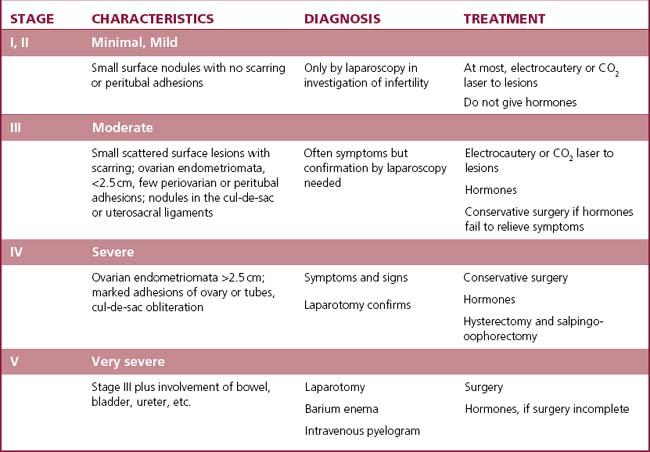

It is often difficult clinically to distinguish endometriosis from pelvic inflammatory disease or an ovarian cyst. Because of this, it is necessary to visualize the lesions through a laparoscope and to biopsy them to confirm the diagnosis. At laparoscopy the extent of the disease should be determined, as this will influence the treatment (Table 35.1).

Management of endometriosis

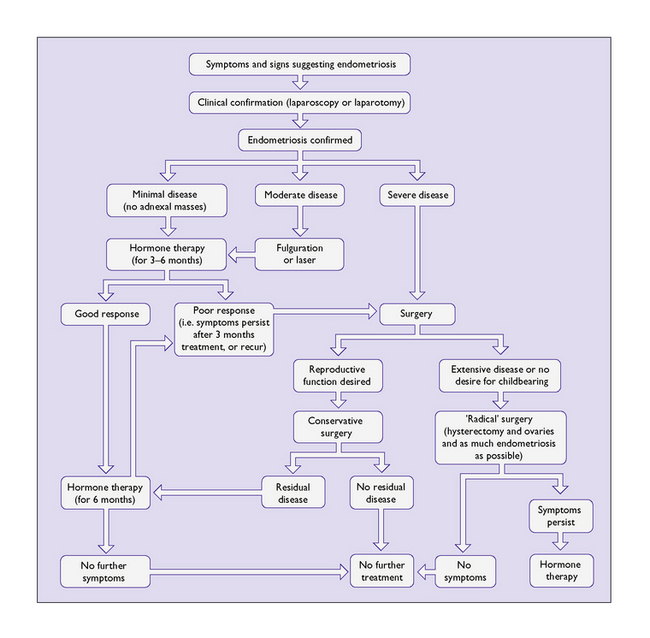

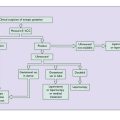

The management of endometriosis depends on the extent of the disease (see Table 35.1), on the severity of the symptoms, and on the desire of the woman to retain her fecundity. In primary care the combined oral contraceptive and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be included. Figure 35.3 is an algorithm showing the management of this disease, details of which will now be discussed.

Hormonal treatment

Longer-term adverse effects of the medications

The first four regimens of treatment, if continued for more than 6 months, lead to bone loss, which is increased if GnRH agonists are used. Some women develop severe hot flushes and other symptoms of oestrogen deficiency. These women, and those who require a longer course of GnRH agonists, can be treated with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (see p. 325), the so-called ‘add-back’ treatment.

Outcome

It should be noted that the more extensive the disease the greater the chance of recurrence.

ADENOMYOSIS

Adenomyosis is the presence of functioning endometrial tissue which has penetrated the myometrium by direct spread from the uterine lining (Box 35.2).

Box 35.2 Adenomyosis

| What is it? | Infiltration of basal endometrial cells into the uterine muscle |

| Aetiology | Unknown |

| Prevalence | Greater in women who are of later reproductive age |

| Diagnosis | Pelvic examination, uterus large and tender |

| Symptoms | Symptomless in a third of women, menstrual irregularities, pain of increasing severity, frequently occurring during menstruation |

| Management | Depends on size and severity of symptoms, no treatment or hysterectomy |

Pathology

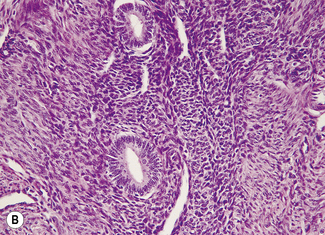

The cells that infiltrate the muscle derive mainly from the basal layer of the endometrium. As this layer is relatively insensitive to hormonal stimulation the adenomyotic nodules tend to be small, containing little blood, but they provoke a marked stromal reaction. The lesion also appears to stimulate myometrial proliferation, causing the tumour to enlarge slowly (Fig. 35.4). Clinically, adenomyosis may be indistinguishable from a myoma, and both may coexist. As the growth of the clinical adenomyoma takes time, clinical adenomyosis tends to occur later in the reproductive years, often in parous women after a long period of secondary infertility.

Clinical features

One-third of patients are asymptomatic. In the remainder the main symptoms are: