Chapter 25 Endometriosis and Adenomyosis

Endometriosis

Endometriosis

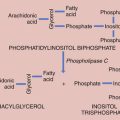

PATHOGENESIS

SITES OF OCCURRENCE

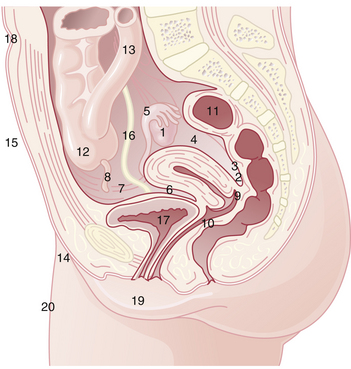

Endometriosis occurs most commonly in the dependent portions of the pelvis. Specifically, implants can be found on the ovaries, the broad ligament, the peritoneal surfaces of the cul-de-sac (including the uterosacral ligaments and posterior cervix), and the rectovaginal septum (Figure 25-1). Quite frequently, the rectosigmoid colon is involved, as is the appendix and the vesicouterine fold of peritoneum. Endometriosis is occasionally seen in laparotomy scars, developing especially after a cesarean delivery or myomectomy when the endometrial cavity has been entered. It is probable that endometrial tissue is seeded into the surgical incision. Two of three women with endometriosis have ovarian involvement.

PATHOLOGY

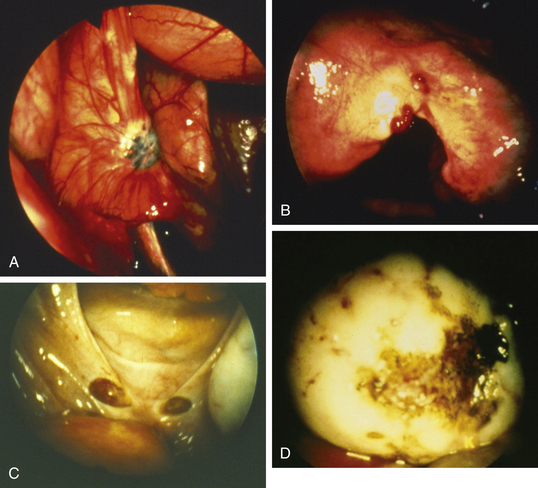

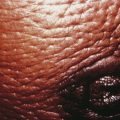

Lesions may be raised and flat with red, black, or brown coloration; fibrotic scarred areas that are yellow or white in hue; or vesicles that are pink, clear, or red (Figure 25-2). The color of the implant is generally determined by its vascularity, the size of the lesion, and the amount of residual sloughed material. Newer implants tend to be red, blood-filled active lesions. Older lesions tend to be much less active hormonally, scarred and blue-gray in color with a puckered appearance. These older inactive lesions have been called the “tattooing of endometriosis.”

STAGING

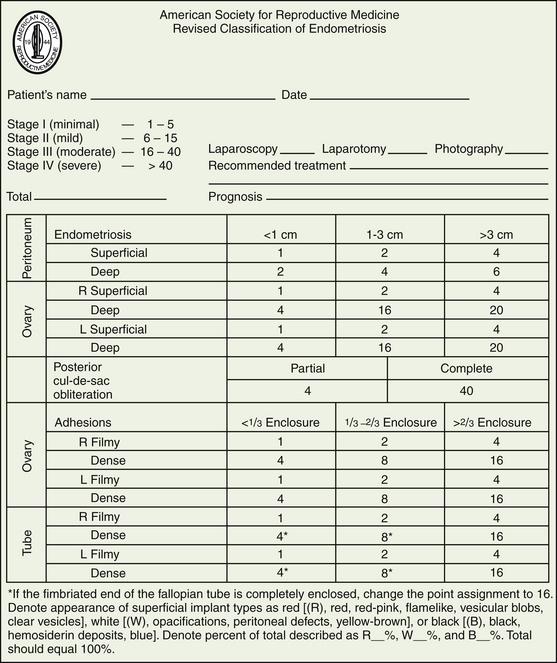

The American Society of Reproductive Medicine employs a staging protocol in an attempt to correlate fertility potential with a quantified stage of endometriosis. This staging, which was initially based on the allocation of points depending on the sites involved and extent of visualized disease (Figure 25-3), was modified to include a description of the color of the lesions and the percentage of surface involved in each lesion type, as well as a more detailed description of any endometrioma.

MANAGEMENT

Medical Treatments

Therapy should be targeted toward relieving the patient’s individual complaints and toward reducing the risk for disease progression. Asymptomatic women found incidentally to have endometriosis may not require any therapy. Dysmenorrhea due to endometriosis can be approached as outlined in Chapter 21, using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and reduction of menstrual flow with hormonal regimens such as low-dose oral contraceptives.

Surgical and medical treatment options for endometriosis are summarized in Box 25-1.

BOX 25-1 Treatment Options for Endometriosis

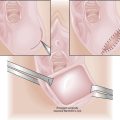

Surgical

Medical

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis

PATHOLOGY

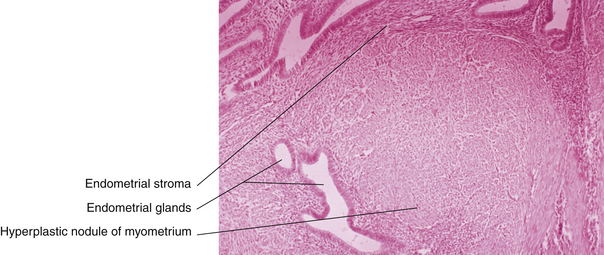

Generally, the gross appearance of the uterus consists of diffuse enlargement with a thickened myometrium containing characteristic glandular irregularities, with implants containing both glandular tissue and stroma (Figure 25-4). The endometrial cavity is also enlarged. Occasionally, the adenomyosis may be confined to one portion of the myometrium and take the form of a fairly well-circumscribed adenomyoma. Contrary to the picture in a uterine myoma, no distinct capsular margin can be detected on cut section between the adenomyoma and the surrounding myometrium. The distinction between adenomyosis and uterine leiomyoma may not always be clear on ultrasonic examination. Figure 25-5 illustrates the typical gross appearance of an enlarged uterus with extensive adenomyosis.

D’Hooghe T.M., Hill J.A. Endometriosis. In: Berek J.S., editor. Berek & Novak’s Gynecology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:1137-1184.

Gambone J.C., Mittman B.S., Munro M.G., et al. Consensus statement for the management of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: Proceedings of an expert-panel consensus process. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:961-972.

Stratton P., Sinaii N., Segars J., et al. Return of chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis after raloxifene treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:88-96.

Wen D., Guo S.W. The search for genetic variants predisposing women to endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:395-401.