Endometriosis

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

Ultrasound Findings

Endometrioma

Decidualized Endometrioma

Deep Penetrating Bowel Wall and Pelvic Implants

Bladder Wall, Ureter, and Anterior Abdominal Wall Lesions (Also See Bladder Masses)

Differential Diagnosis

Endometrioma

Deep Penetrating Bowel Wall and Pelvic Implants

Bladder Wall Lesions

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

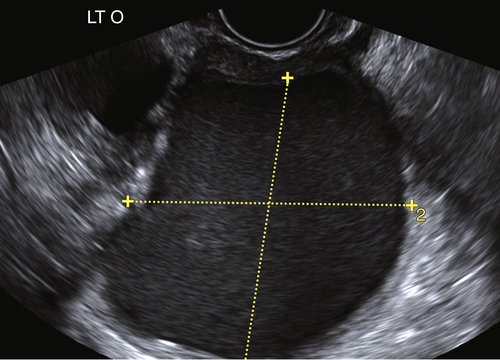

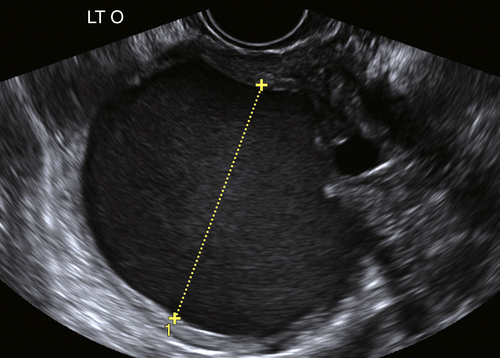

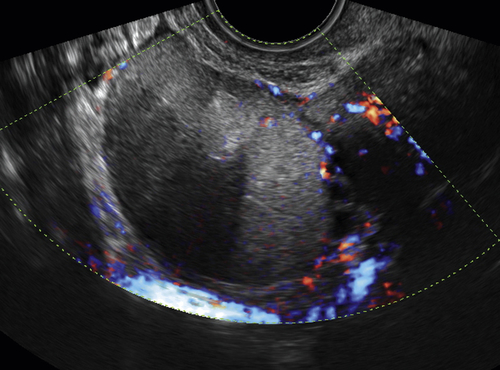

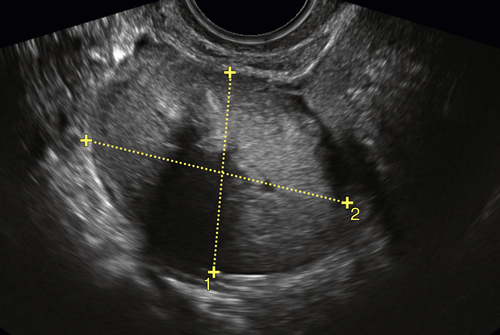

Figures

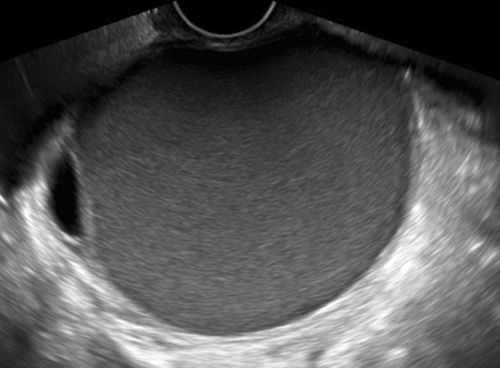

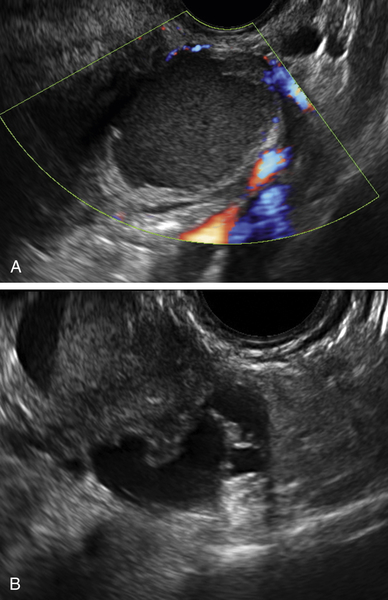

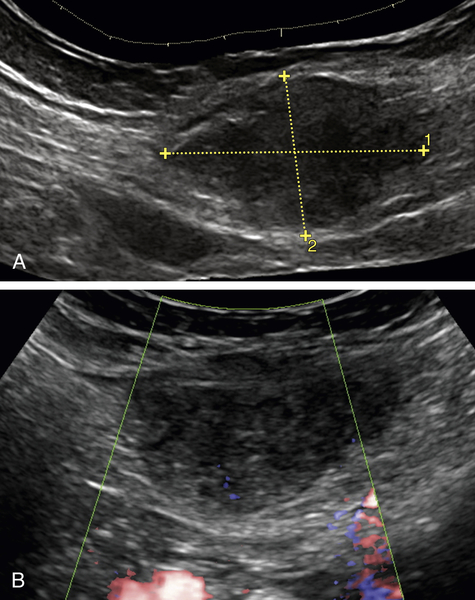

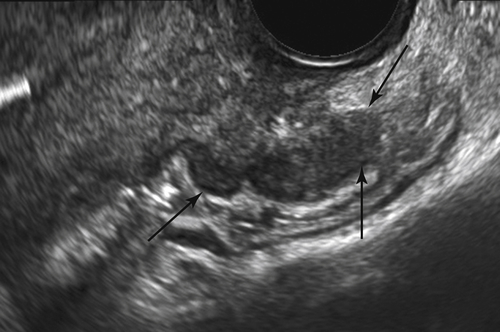

Figure E4-5 A, Cystic mass in a pregnant patient showing an irregular and nodular inner wall with cystic contents displaying low-level echoes. B, Image showing blood flow in the solid areas, a finding that is worrisome for a malignancy. This mass was proved to be a decidualized endometrioma at surgery.

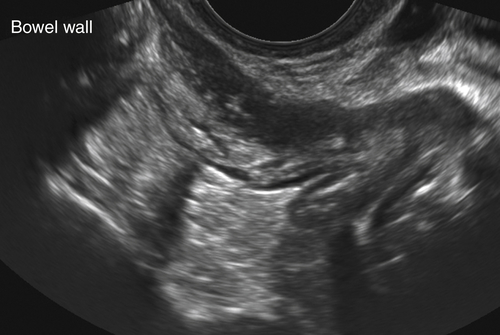

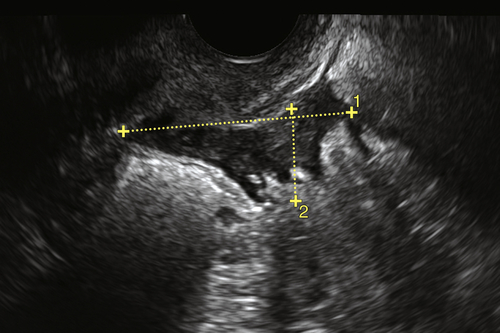

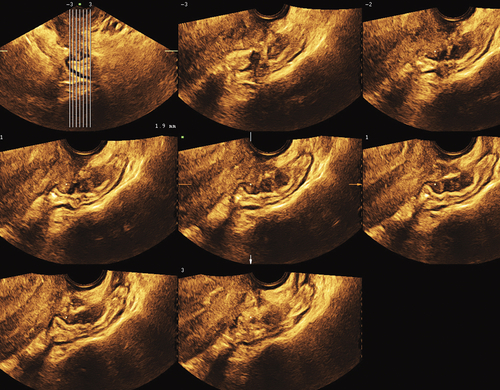

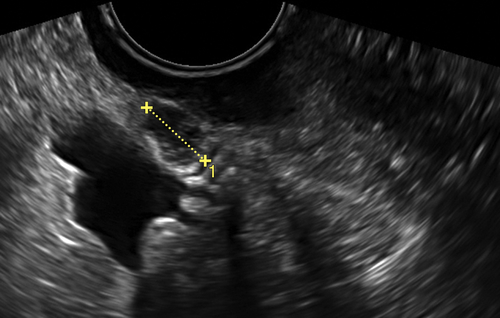

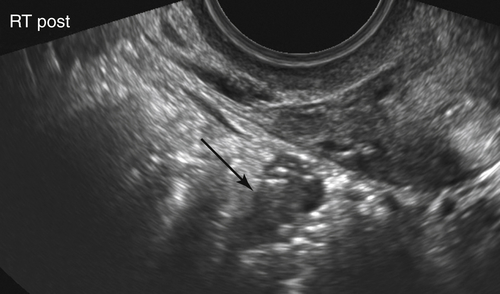

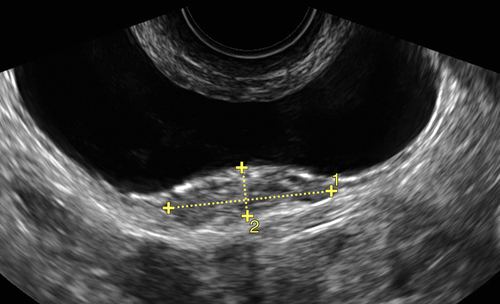

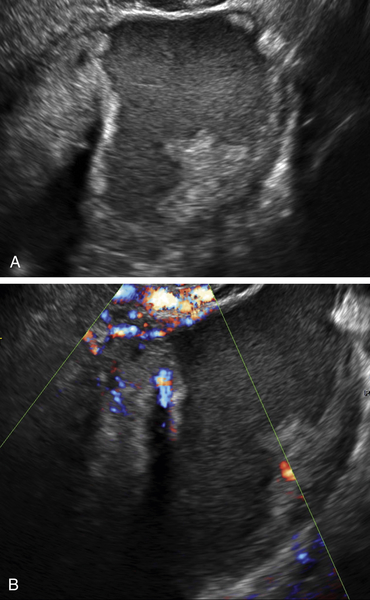

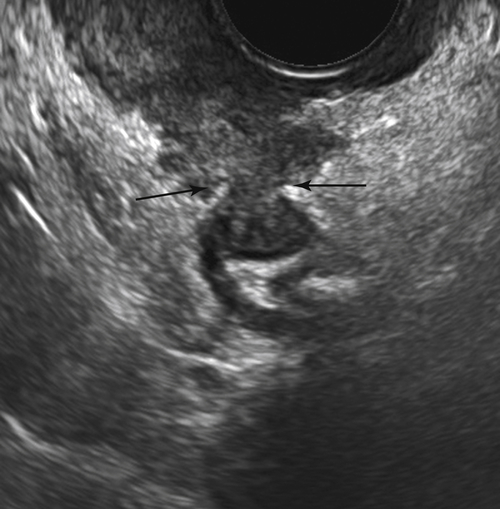

Figure E4-6 Transverse and longitudinal views of the anterior wall of the rectosigmoid, showing solid nodular masses compressing the lumen (arrows). These are typical of endometriotic implants in the bowel wall. Note that the involved bowel is adjacent to the back of the cervix and posterior fornix of the vagina.