Endometrial Carcinoma With Lymph Node Sampling

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Since 1988, endometrial cancer has been regarded by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) as a surgically staged disease. Despite this, at present only a minority of women with endometrial cancer undergo formal surgical staging. The considerable heterogeneity in surgical care for women with endometrial cancer is due to multiple factors: limited access to gynecologic oncologists in some regions, a generally favorable prognosis—particularly with histologic grade 1 disease (Fig. 13–1), and fundamental disagreement regarding the role of pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in women with endometrial cancer.

A full staging procedure for most endometrial cancer consists of a total (extrafascial) hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, as well as pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy and pelvic washings. In available literature, oncologic outcomes are similar for open, laparoscopic, and robotic approaches; the route of the procedure therefore may be individualized to the needs of each patient and surgeon. In some select cases of endometrial cancer that is preoperatively identified to be metastatic to the cervix (stage II), a radical hysterectomy may be chosen by the surgeon. Although the role of surgical cytoreduction is not as well established for endometrial cancer as it is for ovarian cancer, data suggest a survival benefit in cases of metastatic disease when optimal cytoreduction is achieved.

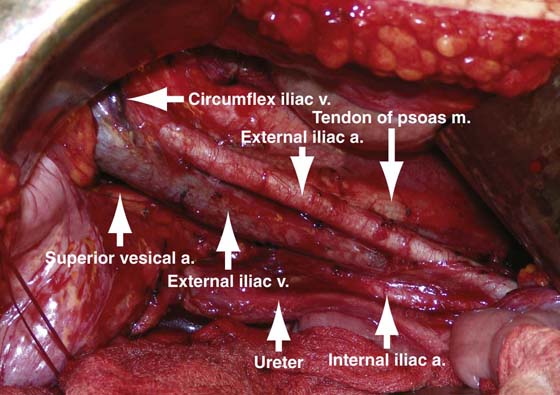

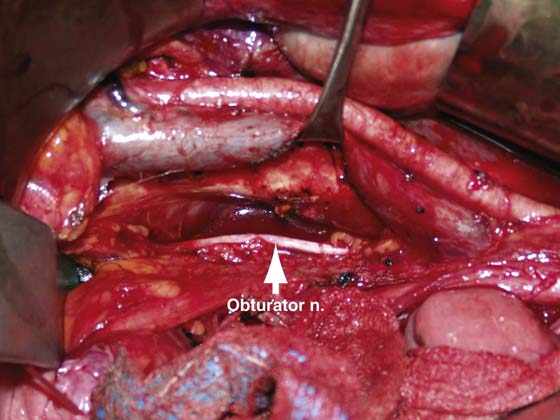

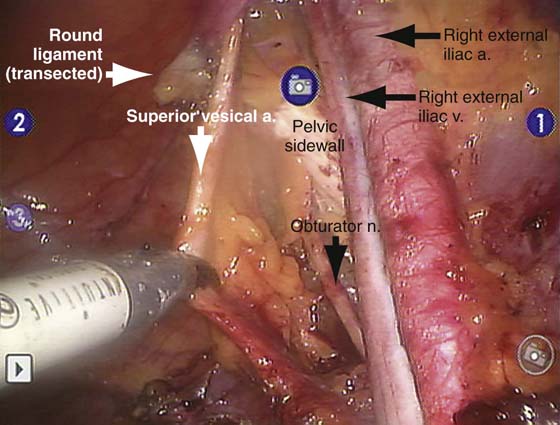

For a pelvic lymphadenectomy (Figs. 13–2 to 13–4) the generally accepted boundaries are as follows: cephalad—mid common iliac artery; caudal—circumflex iliac vein; lateral—pelvic sidewall and mid-psoas muscle; medial—circumflex iliac vein; and dorsal—obturator nerve. Ideally, all nodal and fatty tissue in this anatomically defined region is removed, with hemostasis maintained via cautery or clips. Although additional nodal tissue is present medial to the superior vesical artery and deep to the obturator nerve, this is not routinely sampled in endometrial cancer surgery.

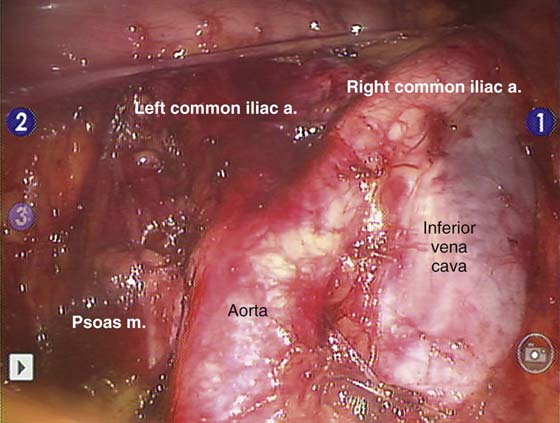

Aortic lymphadenectomy (Fig. 13–5) is less commonly performed than pelvic lymphadenectomy because of a somewhat lower risk of isolated aortic nodal metastases and a more difficult dissection around major vascular structures. Typical boundaries of this dissection include the following: cephalad—ovarian vein on the right and inferior mesenteric artery on the left; caudal—mid common iliac artery; lateral—psoas muscle; medial—mid aorta; and dorsal—spine. Some centers advocate routinely removing the high aortic nodes as well, and continuing this dissection up to the renal veins.

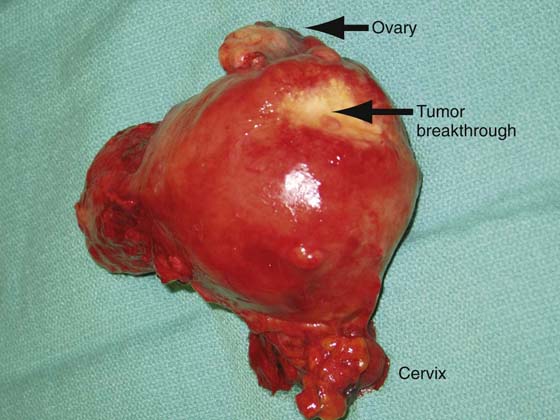

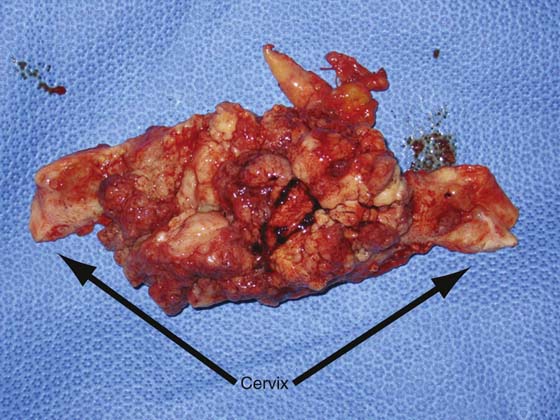

Some authors, both historically and recently, have argued that lymphadenectomy has no therapeutic role in endometrial cancer, and given the potential for morbidity, this phase of the operation should be omitted, except in the presence of grossly metastatic disease. Others will selectively perform lymphadenectomy if the uterine features include deep myometrial invasion or a high-grade tumor (Figs. 13–6 and 13–7). Another perspective is that routine lymphadenectomy allows individualization of care, and when performed systematically and competently, offers a low risk of complications. It is our belief and practice that when combined with the features of the primary tumor, routine and systematic pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy on nearly every patient with endometrial cancer is the most accurate and cost-effective available means of assigning or withholding postoperative adjuvant therapy, with very low attendant morbidity.

FIGURE 13–1 The uterus has been bivalved to demonstrate a relatively small, exophytic grade 1 endometrioid tumor. The risk of lymph node involvement of such a tumor can range from 3% to 6%.

FIGURE 13–2 Pictured is a typical view from the patient left side perspective of a right pelvic lymph node dissection. Most of the anatomic landmarks, including the iliac vessels, ureter, and psoas muscle, can be readily observed.

FIGURE 13–3 This is the same dissection as is shown in Figure 13–2, with the external iliac vein elevated with a vein retractor to expose the obturator space. The obturator nerve and the pelvic sidewall are apparent.

FIGURE 13–4 This laparoscopic image was obtained during robotic right pelvic lymphadenectomy. The definitions of anatomy and quality of dissection are equivalent to those used in an open approach.

FIGURE 13–5 The duodenal reflection and the right ovarian vein are just cephalad to the bottom of this image obtained during robotic bilateral aortic lymphadenectomy. Additional nodal tissue can be seen between the great vessels and at the lateral margin of the vena cava, and it will be removed before the procedure is completed.

FIGURE 13–6 The dimpling on the posterior fundus of this uterus is indicative of full-thickness invasion of a poorly differentiated endometrial tumor, as can be appreciated in Figure 13–7.

FIGURE 13–7 This was a poorly differentiated tumor that had almost completely replaced the myometrium. Such tumors have a very high rate of metastatic spread.

Jack Basil

Jack Basil