12 Endocrinology and metabolism

Hypoglycaemia

Significant hypoglycaemia – defined as blood glucose <2.6 mmol/L (as in Case 12.1) – is rare outside the neonatal period. The symptoms of altered consciousness, pallor and sweatiness are secondary to impaired cerebral metabolism (neuroglycopenia) and adrenaline (epinephrine) release. After a period of fasting, blood glucose levels fall, insulin secretion is suppressed and lipolysis leads to ketone body production. Thus, ketosis during fasting is a normal physiological response. This response is exaggerated in ketotic hypoglycaemia, and ketones rise to toxic levels causing severe acidosis, in addition to the presence of hypoglycaemia, as in Case 12.1. Affected children may have recurrent episodes during illness or after exercise. Treatment is with additional high-energy snacks and carbohydrate-containing drinks at bedtimes and during illness.

Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes mellitus results from progressive immune-mediated destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells, as in Case 12.2. It is increasingly common in children (0.2% of children under 16 years), and the mean age of diagnosis is falling. Insulin deficiency results in progressive hyperglycaemia, weight loss, polydipsia and polyuria (as in Case 12.2). Rapid lipolysis results in production of acidic ketone bodies (ketosis), and ultimately diabetic ketoacidosis, if the symptoms of diabetes are not recognized. For management of diabetic ketoacidosis, see Appendix I, p. 290.

The hypothalamus and pituitary

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland are together the principal command centre of the endocrine system. Pituitary hormones regulate metabolism (TSH), growth (growth hormone) and sexual development (follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone – see ‘Sexual development’ later in the chapter), the adrenal gland (ACTH), water balance (antidiuretic hormone; see Chapter 11, p. 131) and lactation (prolactin and oxytocin). Structural lesions of the hypothalamus and pituitary include congenital malformations and tumours, e.g. craniopharyngioma (see Chapter 7, p. 74), and result in deficiency of some or all of the pituitary hormones – known as hypopituitarism.

The pituitary gland may be congenitally absent or hypoplastic. This may be associated with other midline congenital anomalies such as cleft palate. Congenital hypopituitarism of hypothalamic or pituitary origin may be associated with the development of neonatal hypoglycaemia and, less commonly, cholestatic jaundice secondary to neonatal hepatitis (see also Chapter 13, p. 175).

Adrenal insufficiency

Adrenal insufficiency most often occurs due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia (see p. 152) or secondary to hypopituitarism (as in Case 12.3). Primary adrenal insufficiency is extremely rare. It may be congenital, but it most commonly arises from autoimmune destruction of the adrenal gland, often in association with other autoimmune diseases, notably mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus (polyglandular endocrinopathy), in which case there is often a positive family history. It manifests with insidious malaise, weakness and weight loss and orthostatic hypotension. Hyperpigmentation may occur, classically affecting the buccal mucosa, scars and skin creases.

Physiological steroid replacement with hydrocortisone is essential. This must be doubled or trebled with intercurrent illness, and in severe illness the parenteral route must be used. Failure to give adequate steroid therapy results in adrenal crisis, as in case 12.3, when the patient presents with refractory hypotension, hypoglycaemia, hyponatraemia and variable hyperkalaemia. Prompt treatment with intravenous fluids, glucose and hydrocortisone is essential.

Thyroid gland

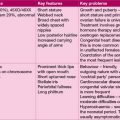

The thyroid gland primarily secretes thyroxine (T4) – a ubiquitous regulator of cell function. The active hormone, tri-iodothyronine (T3), is created by de-iodination of thyroxine in target tissues. Thyroxine secretion is regulated by the hypothalamus and pituitary glands through secretion of thyrotrophin-releasing hormone and consequently thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH secretion increases thyroxine production and may produce enlargement of the thyroid gland – goitre. Excess thyroxine inhibits TSH secretion. See Table 12.1 for the clinical assessment of thyroid function.

| Congenital hypothyroidism | Congenital hyperthyroidism | |

|---|---|---|

| Neonatal onset | Lethargy | Goitre |

| Poor feeding | Low birth weight | |

| Prolonged jaundice | Irritability | |

| Coarse features | Tachycardia | |

| Hoarse cry | Tachypnoea | |

| Umbilical hernia | Hypertension | |

| Mental retardation | Failure to thrive | |

| Juvenile hypothyroidism | Graves’ disease | |

| Childhood onset | Growth failure | Emotional lability |

| Dry skin and hair | Insomnia | |

| Yellow pigmentation | Tremor | |

| (carotenaemia) | Voracious appetite | |

| Intellectual impairment | Goitre | |

| Goitre | Tachycardia | |

| Constipation | Muscle weakness | |

| Cold intolerance | Proptosis | |

| Early puberty (girls) |

Thyrotoxicosis

Hyperthyroidism in older children – usually girls (as in Case 12.4) – is an autoimmune condition. These children make thyroid-stimulating antibodies, which mimic the action of TSH. Although Graves’ disease seems obvious it may be subtle. Irritability, poor exercise tolerance and some thyroid enlargement can be normal in adolescence. The weight loss may be ascribed to anorexia!

Hypothyroidism

Congenital hypothyroidism is a relatively common disorder affecting about 1 in 3500 births. If undetected in early infancy, irreversible mental handicap results. The full syndrome, as described in Case 12.5, is rarely seen, as most developed countries have instituted screening for neonatal hypothyroidism. Occasionally, hypothyroidism detected at birth is temporary, but normally it is a life-long condition. If diagnosed promptly on screening, the progress for growth and intellectual development is good.

Neonatal screening

The advent of neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria has allowed effective treatment for affected children. Treatment at an early stage is completely effective at preventing the poor neurodevelopmental outcomes seen in the past. In the UK, hard-to-reach groups such as travelling families, or newly arrived refugees, may slip through the net, and these diagnoses must be considered. Screening for cystic fibrosis, haemoglobinopathy and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD) is also part of the neonatal screening test (see Chapter 17, p. 250).

Phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is normally detected by the neonatal screening test, which is performed once a child is established on feeds at 5 to 9 days old. In Case 12.6, early treatment with dietary restriction of phenylalanine would have prevented its toxic effect on the brain, which is largely irreversible. PKU is caused by deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase, which prevents phenylalanine (an essential amino acid) being converted to tyrosine, and toxic metabolites accumulate.

Children born to mothers with PKU are at risk of mental retardation if the diet is not very strictly observed from before conception and throughout pregnancy (see Chapter 18, p. 265).

Growth

Phases of growth

Infant growth

Faltering growth (failure-to-thrive)

Case 12.7 highlights the importance of a nurturing environment, and adequate food intake in infant growth. Hormone imbalance is very rare as a cause of faltering growth in infancy. Relevant considerations when seeing a baby with failure-to-thrive are:

• Is there an underlying pathological cause for growth failure, or is the baby constitutionally small?

• Does poor weight gain reflect poor food supply and intake or nutrient loss through vomiting?

See Table 12.2 for the principal causes of failure-to-thrive.

| Classification | Diagnosis | Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate intake | Neglect Failure of breast-feeding Cleft palate |

Observation |

| Vomiting | Gastrooesophageal reflux Pyloric stenosis |

Observation, upper gastrointestinal barium study, abdominal ultrasound |

| Malabsorption | Cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease Milk intolerance |

Sweat test Coeliac antibodies, upper small bowel biopsy Stool sugar chromatography, urine reducing substances, trial of alternative milk |

| Renal | Urinary tract infection | Urine culture |

| Cardiac | Congenital heart disease | Echocardiogram |

| Respiratory | Infection | Nasopharyngeal aspirate, chest X-ray |

| Constitutional | Chromosomal disorders Congenital syndromes Inborn errors of metabolism Perinatal infections |

As appropriate |

Growth in childhood

Short stature

For practical purposes in the UK, short stature is defined as height less than the 2nd centile; however, this definition includes 1 in 50 normal, healthy children. The 0.4th centile includes only 1 in 250 normal but short children, and the likelihood of an underlying pathological cause for short stature is much higher. An individual height measurement is a ‘snapshot’ of growth, and previous height measurements are extremely helpful. The child who has always been short is more likely to be normal, whereas the child who has shown poor growth and is crossing centiles should provoke concern, even if still within the normal range. Only a small number (<10%) of short children have an endocrine cause for short stature. See Table 12.3 for the causes of short stature.

| Cause | Diagnostic factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Parental heights Growth follows centile line |

|

| Emotional | History of deprivation Withdrawn or disturbed behaviour |

|

| Syndromes | Turner syndrome Achondroplasia Russell–Silver syndrome |

Girls Dysmorphic features Delayed puberty Abnormal body proportions Short limbs Low birth weight Triangular facies |

| Loss of growth potential | IUGR Severe early illness |

Low birth weight For example, extreme prematurity or malnutrition |

| Chronic illness | Evidence of the illness Remember the effect of steroids |

|

| Endocrine | Growth hormone deficiency | Growth crossing centile lines Obesity Dysmorphic features |

Psychosocial growth failure

In contrast to organic causes of growth failure, the effects of emotional deprivation on growth are hard to define and to diagnose. Case 12.8 is fairly cut and dried but the diagnosis must always be considered.

In Case 12.9, the severity of the boy’s short stature, his physical characteristics and the history of neonatal hypoglycaemia were strongly suggestive of growth hormone deficiency, which was confirmed by a growth hormone test. Subsequently, an MRI scan showed an empty pituitary fossa due to congenital absence of the anterior pituitary. In these cases the posterior pituitary is often abnormally placed (ectopic).

Use of growth hormone in children

Current indications for growth hormone treatment in the UK include:

• Turner syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 278)

• Prepubertal children with chronic renal failure

• Short children >3 years, born small for gestational age

• Prader-Willi syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 276).

• SHOX deficiency – the SHOX gene (short stature homeobox gene on X) is present on the X and Y chromosomes. Deficiency of SHOX contributes the majority of the growth failure seen in Turner’s syndrome. SHOX deficiency also occurs as an isolated condition due to genetic mutations affecting SHOX.

Sexual development

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the commonest cause of impaired adrenal steroid secretion in childhood. This results from inborn errors affecting steroidogenic pathways – principally 21-hydroxylase, which accounts for over 95% of CAH. The inability to synthesize cortisol leads to hypersecretion of ACTH, which in turn produces adrenal hyperplasia. As 21-hydroxylase also mediates aldosterone synthesis, severe enzyme deficiency leads to loss of aldosterone also, and results in salt-losing CAH. The block in cortisol synthesis results in cortisol precursors being converted into androgens. The diagnosis is confirmed by the finding of elevated 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone (as in Case 12.10).

Puberty

In boys, puberty is signalled by testicular enlargement. Testicle size may be assessed with an orchidometer (see Figure 12.1). Puberty starts when testicular size reaches 4 mL, progressing through puberty to 15–25 mL in adulthood. In boys, puberty normally starts between 10 and 14 years. The first visible sign of puberty is the appearance of pubic hair, followed by growth of the penis. Testicular size of 12 mL is attained by mid-puberty, when nocturnal FSH secretion reaches adult levels. This corresponds both to the timing of the first ejaculation and the peak of the adolescent growth spurt. Growth continues until epiphyseal fusion occurs in the mid to late teens.

Figure 12.1 Orchidometer for assessment of testicular size in boys. The numbers indicate size in millilitres.

There are a number of normal variants of puberty:

1. Premature thelarche describes the appearance of breast tissue, sometimes unilateral, in female infants and young girls. The breast size fluctuates, and prolactin and oestrogen levels are in the normal prepubertal range. It remits spontaneously by 2 or 3 years of age.

2. Premature adrenarche is a result of the secretion of adrenal androgens by the adrenal cortex. It typically occurs in girls in mid childhood and may result in the development of body odour, acne, and axillary and pubic hair. Oestrogen levels are prepubertal. Measurement of the exclusive adrenal androgen dehydroepiandrosterone or its sulphate confirms the diagnosis.

3. Gynaecomastia is breast development in boys. It occurs to some degree in all boys in early to mid puberty, but may be pronounced, particularly in obese boys. Where gynaecomastia leads to social difficulties, such as severe embarrassment or school refusal, surgery may be appropriate.

Precocious puberty

In central precocious puberty, as in Case 12.11, gonadotrophin levels are elevated to pubertal levels, with elevated oestrogen or testosterone. Central precocious puberty is relatively common in girls, and is usually idiopathic, but in a small number there is an underlying cause such as a hypothalamic hamartoma or hydrocephalus. In contrast, central precocious puberty in boys is nearly always abnormal. Severe hypothyroidism may cause precocious puberty in girls, but unlike other causes of early puberty, there is no accompanying growth spurt. In boys, testicular enlargement, but not true puberty, is seen.

Delayed puberty

Pathological causes of delayed puberty can result from abnormalities in pituitary production of gonadotrophins or disorders of the testis or ovary. Measuring gonadotrophin levels (FSH and LH) in the blood will distinguish these. Investigation will also include chromosomal analysis as Turner syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 278) in girls (as in Case 12.12) and Klinefelter syndrome in boys (XXY karyotype; see Chapter 18, p. 274) each cause gonadal failure and pubertal delay. In contrast to Turner syndrome, boys with Klinefelter syndrome are tall. Lack of pubertal development with absent sense of smell (anosmia) occurs in Kalman syndrome.