14 Endocrinology and Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus

The likelihood is that this patient has type 2 diabetes (Table 14.1). The risk of ketoacidosis is small and he will not need admission unless he is either ketotic (ketonuria 3+) or is very dehydrated.

Table 14.1 The spectrum of diabetes: a comparison of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Younger (usually < 30 years of age) | Older (usually > 30 years of age) |

| Usually lean | Often overweight | |

| Increased in those of Northern European ancestry | All racial groups. Increased in peoples of Asian, African, Polynesian and American-Indian ancestry | |

| Seasonal incidence | ||

| Heredity | HLA-DR3 or DR4 in > 90% | No HLA links |

| 30–50% concordance in identical twins | ~ 50% concordance in identical twins | |

| Pathogenesis | Autoimmune disease | No immune disturbance |

| Islet cell autoantibodies | Insulin resistance | |

| Insulitis | ||

| Association with other autoimmune diseases | ||

| Immunosuppression after diagnosis delays beta-cell destruction | ||

| Clinical | Insulin deficiency | Partial insulin deficiency initially |

| May develop ketoacidosis | May develop hyperosmolar state | |

| Always need insulin | Many come to need insulin when beta-cells fail over time | |

| Biochemical | Eventual disappearance of C-peptide | C-peptide persists |

Note: there is a significant rise in the incidence of young patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, especially in the obese and in Asian populations.

Indications for admission

Information

Diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus:

• Fasting venous plasma glucose > 7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) after 8-h fast*

• Random venous plasma glucose > 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL)*

• An HbA1c of > 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) has recently been approved for diagnosis (Table 14.2)

• Impaired fasting glucose: 5.6–6.9 mmol/L

• Impaired glucose tolerance: > 7.8 and < 11.1 mmol/L; 2 h after 75 g oral GTT.

Table 14.2 HBA1c – conversion of percentage values to mmol/mol

| DCCT HbA1c % | IFCC HbA1c mmol/mol |

|---|---|

| 4.0 | 20 |

| 5.0 | 31 |

| 6.0 | 42 |

| 6.5 | 48 |

| 7.0 | 53 |

| 7.5 | 59 |

| 8.0 | 64 |

| 9.0 | 75 |

| 10.0 | 96 |

DCCT, Diabetes control and complication trial.

IFCC, International Federation of Clinical Chemistry.

An oral glucose tolerance test is only required for borderline cases.

Progress.

This patient is much more likely to be presenting with early type 1 diabetes and might not be ketotic yet because he could still have a degree of residual beta cell function (the ‘honeymoon’ phase). Again, assessment of ketosis, acidosis and dehydration must be made to determine whether he needs admission. He should be seen within 24 h either by the diabetic liaison nurse or in hospital to commence insulin. If there is any doubt, the patient should be seen in A&E immediately.

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

How do patients present with ketoacidosis?

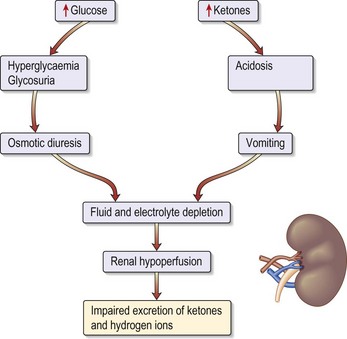

Patients known to have type 1 diabetes mellitus most commonly develop ketoacidosis when insulin is omitted because of missed meals during an intercurrent illness (e.g. gastroenteritis). Patients become rapidly dehydrated (Fig. 14.1) and acidotic (over hours). Tachypnoea or Kussmaul respiration (a deep sighing respiration) is prominent, with the smell of ketones on the breath. It is the fall in pH that causes coma.

Assessment of severity

Management: general measures

• Insert a central line in patients with a history of cardiac disease/renal impairment/autonomic neuropathy or the elderly.

• An arterial line to monitor ABGs and plasma potassium.

• Nil by mouth for at least 6 h.

• Nasogastric tube: if there is impaired conscious level, to prevent vomiting and aspiration.

• Urinary catheter: if no urine for 2 hours or serum creatinine is high.

Management: fluid replacement

Severely shocked patients may require colloid to restore circulating plasma volume. Table 14.3 shows examples of blood values in severe ketoacidosis and compares these with those seen in the hyperosmolar, hyperglycaemic state described on page 418.

The guidelines for fluid replacement are shown in Table 14.4. These are applicable for young patients.

• When blood glucose falls to less than 12 mmol/L convert to a 5% glucose infusion. This will enable the insulin infusion to be continued. Continued insulin is required to inhibit ketone production.

• Continue with IV fluids 1 L every 4–6 h until rehydrated and ketosis resolves (~24 h).

Table 14.4 Guidelines for average fluid replacement in young patients

| Volume | Duration/timing |

|---|---|

| 1 L 0.9% saline + 20 mmol/KCl | Over the first 30 min |

| 1 L 0.9% saline + 20 mmol/KCl | Over next 1 h |

| 1 L 0.9% saline + 20 mmol/KCl | Over next 2 h |

| 1 L 0.9% saline + 20 mmol/KCl | Over next 4–6 h |

Management: insulin regimen

• Add 50 units of soluble insulin to 50 mL 0.9% saline and administer by intravenous infusion; this equates to 1 U/mL.

• Commence at 6 U/h and continue at 3 U/h after venous glucose falls to < 11.5 mmol/L.

• Glucose must then be administered to prevent hypoglycaemia (see above).

• Continue IV insulin infusion until ketosis resolves, the patient is eating and for 2–4 h after the first SC dose of soluble insulin.

Management: potassium replacement (Table 14.5)

• Monitor serum [K+] every 2 h initially then every 4 h until stable.

• Use premixed potassium-containing infusions wherever possible.

Table 14.5 Potassium replacement in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | Amount of KCl (mmol/hour) |

|---|---|

| <3 | 40 |

| 3–1 | 30 |

| 4–5 | 20 |

| 5–6 | 10 |

| > 6 | Stop KCl |

Assessment during treatment

• Remember the role of insulin is primarily to suppress ketogenesis rather than to lower blood glucose.

• Blood glucose (BM Stix every hour, laboratory blood glucose 4-hourly).

• Plasma potassium every 4 h: the main risk is hypokalaemia.

• Repeat ABGs after 2 h. A calculated anion gap (needs chloride estimation) may be adequate for monitoring.

Hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state

How do patients present?

Diagnosis and investigations

• Plasma glucose: usually > 40 mmol/L.

• U&Es: significant hypernatraemia occurs but this is masked by the high glucose. The [Na+] usually increases as the venous glucose and therefore the extracellular colloid osmotic pressure falls and water moves into the intracellular space.

• Arterial blood gases: relatively normal.

• Plasma osmolality: typically > 350 mOsmol/kg.

• Estimate corrected sodium to evaluate water loss as a result of hyperglycaemia (see Information box).

• FBC: may show polycythaemia, dehydration or a leucocytosis from infection.

• CK: cardiac ischaemia or rhabdomyolysis.

• ECG: for myocardial infarction or ischaemia.

How would you manage this patient?

General treatment measures

• Aim to correct the high osmolality with fluid and insulin over 48–72 h. Avoid fluid overload and insert a central venous line if cardiac problems.

• When blood glucose is less than 10 mmol/L, commence a 5% glucose infusion.

• Once stable, stop insulin therapy and commence oral hypoglycaemic agents or diet alone.

Hypoglycaemic coma

How do patients present? (Table 14.6)

| Sympathetic overactivity (glucose < 3.5 mmol/L) | Neuroglycopenia (glucose < 2.6 mmol/L) |

|---|---|

| Tachycardia | Confusion |

| Palpitations | Slurred speech |

| Sweating | Localised neurological impairment |

| Anxiety | Coma |

| Pallor | |

| Tremor | |

| Cold extremities |

Assessment of severity

• Hypoglycaemia in a patient with diabetes is defined as < 3.5 mmol/L.

• A ‘mild’ episode requires intervention by the patient.

• A ‘severe’ episode might lead to coma and requires treatment by a third party.

Investigations

Patients with diabetes with frequent hypoglycaemic attacks:

• Urea and electrolytes: hypoglycaemia is more common in diabetic nephropathy because the kidney is one of the sites of insulin metabolism

• Thyroid function tests: hypothyroidism is associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus and impairs counter-regulation

• 09:00 cortisol ± short ACTH (tetracosactide) stimulation test: hypoadrenalism reduces hepatic glycogen stores (see p. 443)

How would you manage hypoglycaemia?

Unconscious patient

• Do not use 50% glucose in peripheral veins.

• Once recovered, give 1–2 slices of bread or 2–4 biscuits.

• Admit the patient if the cause is a long-acting sulphonylurea or a long-acting insulin and give a continuous infusion of 10% glucose (e.g. 1 litre 8-hourly) and check glucose hourly or 2-hourly.

• Patients should regain consciousness or become coherent within 10 min, although complete cognitive recovery might lag by 30–45 min. Do not give further boluses of IV glucose without repeating the blood glucose. If the patient does not wake up after 10 min or more, repeat the blood glucose and consider another cause of coma – stroke or a head injury during their confused state.

Sick diabetic patient

Treatment/progress

This patient has a diagnosis of STEMI and requires immediate therapy with aspirin 300 mg chewed and clopidogrel 300 mg oral gel. He was immediately transferred to the Coronary Care Unit for further assessment and possible percutaneous coronary intervention, which is instantly available (p. 285). His diabetes was initially controlled on insulin infusion because he was nil by mouth for the cardiac procedures (Table 14.7). The infusion was continued until the patient was eating and drinking. Insulin treatment has been proven to improve outcome in patients with diabetes in the immediate period after myocardial infarction.

Table 14.7 Intravenous infusion insulin management of type 1 diabetes mellitus in hospital

| Level of blood glucose (measured hourly) | Insulin infusion (units per hour) |

|---|---|

| < 4.0 mmol/L | 0.5 |

| 4.0–7.0 mmol/L | 1 |

| 7.1–9.0 mmol/L | 2 |

| 9.1–11.0 mmol/L | 3 |

| 11.1–14.0 mmol/L | 4 |

| 14.1–17.0 mmol/L | 5 |

| 17.1–28 mmol/L | 6 |

| > 28 mmol/L | 8 |

Note: the above is only a guide and insulin doses should be adjusted upwards if the patient is known to have a high insulin requirement, and always reviewed regularly to see if the doses are appropriate. The aim is to keep blood glucose in the 7–9 region.

Protocol for converting diabetics from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin

• Calculate total dose over last 24 h.

• Give 25% of total as soluble insulin 30 min before each meal (i.e. × 3 daily).

• Give 25% of total dose as intermediate-acting isophane insulin at 22:00.

• Monitor blood glucose fasting and 2 h after meals (post-prandial) – each finger-prick glucose measures the adequacy of the previous dose.

• Aim for glucose < 10 mmol/L post-prandial and < 8 mmol/L fasting.

• Do not discontinue IV insulin until 1–2 h after the first subcutaneous insulin dose is administered, because IV insulin has a half-life of only 3 min.

Management of new type 2 diabetic presenting for surgery

How would you manage this patient?

• Ask about symptoms of diabetes, e.g. thirst, polyuria, lack of energy.

• Check that a laboratory glucose has been sent to confirm the diagnosis of diabetes (random glucose 13.4 mmol/L).

• Discuss patient’s angina symptoms and discuss with cardiologist the urgency of CABG surgery.

• It is agreed by all, including the patient, that his diabetes should be treated and blood sugar controlled before surgery is performed.

• The patient is referred to the Diabetic Liaison Nurse for assessment and discussion of treatment as an outpatient.

Remember

Always get diabetes under control before patients undergo surgery unless this is an emergency.

Information

Assessment of new patients with diabetes

• Biochemical assessment of long-term glycaemic control (e.g. HbA1c)

• Examine the retina through dilated fundi (ophthalmoscope initially followed by retinal photo)

• Test blood for renal function (creatinine and eGFR)

• Check general condition of the feet, peripheral pulses and sensation

• Review cardiovascular risk factors

• Introduce self-monitoring and injection techniques if insulin is required

Management for surgery

Non-insulin-treated patients should stop medication 2 days before the procedure. Patients with mild hyperglycaemia (fasting blood glucose < 8 mmol/L) can be treated as non-diabetic. Those with higher levels are treated with soluble insulin prior to the procedure/surgery, and with glucose, insulin and potassium infusion during and after the procedure (p. 426). Be careful of hypoglycaemia due to the additive effect of medications taken previously. Postoperatively, patients should return to their normal management regimen when they begin eating and drinking.

Who needs insulin perioperatively?

• All patients who usually use insulin

• All acute surgical emergencies (type 1 and type 2 diabetes)

• All patients undergoing major surgery (type 1 and type 2 diabetes).

In other words, all diabetic patients should receive insulin except type 2 diabetic subjects undergoing minor surgery. For patients on insulin, give the usual evening and/or night-time insulin and commence glucose and insulin as above at 06:00.

Urgent surgery in patients with diabetes

The procedure for insulin-treated patients is simple:

Preoperative glucose levels should be in the range of 7–11 mmol/L.

Postoperatively, the infusion is maintained until the patient is able to eat. Other fluids needed in the perioperative period must be given through a separate IV line and must not interrupt the glucose/insulin/potassium infusion. Glucose levels are checked every 2–4 hours and potassium levels are monitored. The amount of insulin and potassium in each infusion bag is adjusted either upwards or downwards according to the results of regular monitoring of the blood glucose and serum potassium concentrations.

Diabetic foot

Case history

On examination she has a 2-cm ulcer on the medial side of her big toe with swelling and erythema.

What further points would be helpful in the history?

• Is there a previous history of foot problems?

• Does she regularly inspect and wash her feet? Is she careful about buying shoes of the correct size?

• Does she live alone? Does she have any help?

• Is there any suggestion of peripheral vascular disease, e.g. intermittent claudication?

• Is there any suggestion of peripheral sensory problems? Does she complain of numbness or burning in her feet?

What particular points do you look for on examination?

Management

• Admit the patient to a medical assessment unit.

• Take swabs for microbiology.

• Arrange an urgent X-ray to look for foreign bodies, gas and osteomyelitis.

• Early effective antibiotic treatment is essential:

• Control the diabetes with insulin until foot healed, when oral treatment can be restarted.

• Establish the presence of other diabetic complications (see above).

• Ask diabetic team to fully assess her and arrange for future follow-up care.

Diabetes in pregnancy

How should this patient be managed?

Information

Cushing’s syndrome

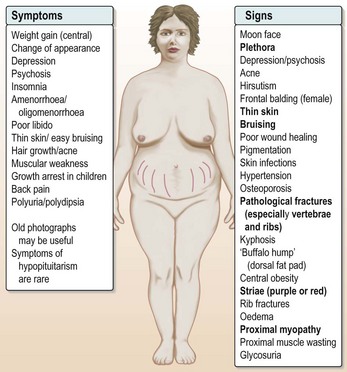

Other complications follow, including secondary infection, bruising and bleeding, uncontrollable hypertension and osteoporotic fractures (Fig. 14.2).

How would you manage this patient?

• Start potassium replacement both orally and intravenously (not more than 20 mmol in any 3 h) to provide at least 200 mmol per day.

• Rehydrate the patient with 0.9% saline + potassium chloride (40 mmol/L) added to each bag (see p. 426) with 2-hourly K+ monitoring.

• Start an intravenous infusion of insulin at 4 units per hour. This might exacerbate the fall in serum potassium.

• After 48 hours the lady was rehydrated with a serum K+ of 4.5 mmol/L.

Hyperthyroidism

Case history (1)

ECG shows fast AF 160/min but no evidence of cardiac ischaemia or other abnormality.

What should you do?

• Admit the patient to HDU and start treatment of acute heart failure, oxygen, IV furosemide 50 mg and vasodilation therapy glyceryl trinitrate infusion 100–200 µg min.

• She responds well but still has fast AF.

• Urgent. Thyroid function tests reveal a free T4 of 45 pmol/L (NR 9.0–23) with a suppressed TSH.

Treatment

• Control the heart rate using beta blockers (propranolol 40 mg every 8 h) and digoxin if required.

• Avoid amiodarone as this will potentially interfere with investigation and management.

• Anti-coagulate the patient (heparin and warfarin).

• Start anti-thyroid medication, e.g. carbimazole 40 mg daily.

Beta adrenoreceptors are sensitised to normal circulating catecholamines by high levels of thyroxine and beta blockade is useful in achieving symptom control in hyperthyroidism, and is also helpful in treating high-output heart failure and achieving rate control. Propranolol is used in high doses (40 mg every 8 h) because, being lipid soluble, it crosses the blood–brain barrier.

Brent GA. Graves’ disease. NEJM. 2008;358:2594–2605.

Case history (2)

A 75-year-old woman is referred with weight loss, general malaise and apathy.

Clinical examination is unremarkable except for a mild tachycardia of 100 bpm.

Routine investigations (remembering to include thyroid function tests) (Table 14.8), have now been telephoned by the biochemist with the following results:

Elderly patients can have atypical presenting features of hyperthyroidism, which may be dominated by weight loss, apathy and fatigue.

Tests in patients with goitres

• Thyroid function tests – TSH plus free T4 or T3.

• Thyroid antibodies – to exclude auto-immune aetiology.

• Ultrasound. Ultrasound with high resolution is a sensitive method for delineating nodules and can demonstrate whether they are cystic or solid. In addition, a multinodular goitre may be demonstrated when only a single nodule is palpable. Unfortunately, even cystic lesions can be malignant and thyroid tumours may arise within a multinodular goitre; therefore fine-needle aspiration (see below) is often required and performed under ultrasound control at the same time as the scan.

• Fine-needle aspiration (FNA). In patients with a solitary nodule or a dominant nodule in a multinodular goitre, there is a 5% chance of malignancy; in view of this, FNA should be performed. This can be done in the outpatient clinic. Cytology in expert hands can usually differentiate the suspicious or definitely malignant nodule.

• FNA reduces the necessity for surgery, but there is a 5% false-negative rate which must be borne in mind (and the patient appropriately counselled). Continued observation is required when an isolated thyroid nodule is assumed to be benign without excision.

• Thyroid scan (99m technetium) can be useful to distinguish between functioning (hot) or non-functioning (cold) nodules. A hot nodule is only rarely malignant; however, a cold nodule is malignant in only 10% of cases and FNA has largely replaced 99m technetium scans in the diagnosis of thyroid nodules.

Drug treatment in hyperthyroidism

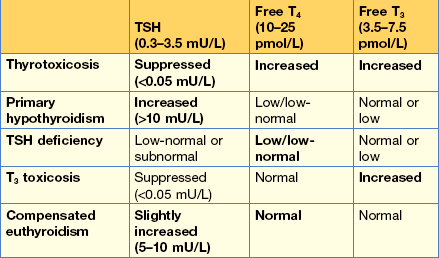

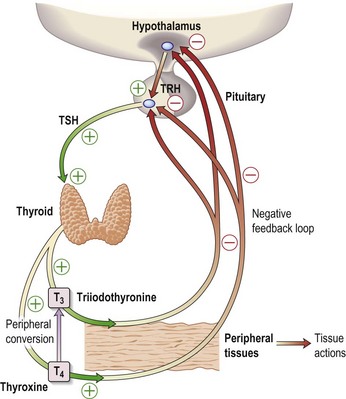

The latter two drugs inhibit the formation of thyroid hormones (Fig. 14.3). Carbimazole and PTU will induce hypothyroidism after 4–8 weeks at these doses and treatment should either be titrated down to a maintenance level (e.g. carbimazole 10 mg daily) or thyroxine added back at a dose of 100–150 µg in a ‘block and replace’ regimen. Patients are typically treated for 6–18 months with anti-thyroid drugs. All patients commencing anti-thyroid drugs should be warned about possible rashes, which are common and usually self-limiting without discontinuation, and severe sore throats or mouth ulcers, which may indicate a dangerous fall in neutrophils.

Information

Investigation of a solitary nodule

• All solitary nodules > 1 cm should be evaluated, as should ‘dominant’ nodules in nodular goitres

• Fine-needle aspiration cytology is the first-line investigation to identify a papillary carcinoma or follicular neoplasm

• Ultrasound is used to diagnose multinodular goitre

• Isotope scanning might identify a toxic ‘hot’ solitary nodule; these are almost always benign

Features of viral (de Quervain’s) thyroiditis

• Neck discomfort or pain on swallowing and a short course of prednisolone is used if pain is severe

• Hyperthyroidism (usually 1–3 weeks followed by hypothyroidism), followed by resolution

• Disparity between clinical features and biochemistry

Patients who have two or more of the above have a high mortality. Symptoms can also include vomiting, diarrhoea, seizures and coma.

Thyroid storm

Treatment

• Cool the patient with tepid sponging and a fan. Do not use aspirin, which is contraindicated in thyroid storm (it displaces thyroxine from its binding globulin and increases the free T4).

• Beta blockers (propranolol 5 mg IV then 40–80 mg 8-hourly orally) unless contraindicated by asthma (Note: heart failure is not a contraindication to beta blockers).

• Fluid replacement: this needs careful assessment with central venous monitoring. Heart failure will rapidly come under control once the patient’s heart rate is lowered.

• Hydrocortisone 100 mg IV 6-hourly. This blocks T4 to T3 conversion.

• Propylthiouracil 250 mg 4-hourly.

• Potassium iodide 60 mg 8-hourly as iodine blocks thyroxine synthesis and release. This should be given at least 1 h after the propylthiouracil, which blocks iodine incorporation, but not uptake.

Amiodarone and thyroid function

Case history

On examination she has an irregular pulse 120/min, a raised JVP with crackles at both bases.

You diagnose mild heart failure with atrial fibrillation which is confirmed by ECG.

Treatment

On post-take ward round:

• Confirm how long the patient has been on amiodarone and check the clinical record to establish whether there are any previous TFT results, particularly those before amiodarone therapy was commenced.

• Amiodarone can cause hypo- or hyperthyroidism. In patients who have nodular thyroid disease the synthesis of thyroxine may be autonomous and is limited only by iodine availability: thyrotoxicosis may be precipitated. In others, the Wolff–Chaikoff effect may result in hypothyroidism. Amiodarone also blocks T4 to T3 conversion, causing a high T4 and normal T3.

• Examine the patient for clinical evidence of hyperthyroidism.

• The patient is clinically, as well as biochemically thyrotoxic, so start carbimazole 40 mg daily and ask the patient’s cardiologist to discontinue amiodarone and use other therapy for her atrial fibrillation. Amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis can require high doses of carbimazole and sometimes prednisolone is helpful in controlling the condition. Because amiodarone contains large amounts of iodine, radioiodine cannot be used.

Hypothyroidism

Case history

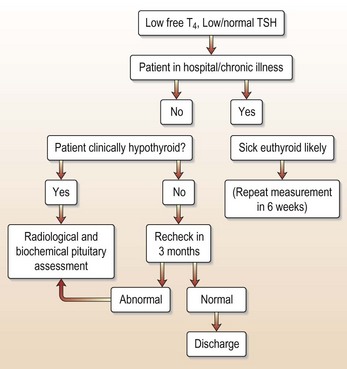

Investigations show a raised TSH (30 µg/L) and free T4 of 4.2 pmol/L, confirming hypothyroidism. Interpretation of thyroid function tests is shown in Figure 14.4.

Hypothyroidism is now diagnosed by a multitude of practitioners:

• Lipid clinic: cause of hypercholesterolaemia

• Psychiatrists: organic psychosis or depression

• ENT surgeons: dysphonia or deafness

• Cardiologists: during follow-up on amiodarone treatment

• Dermatologists: dry skin or hair

• Gynaecologists: menorrhagia, oligo- or amenorrhoea, infertility

In primary hypothyroidism, the TSH will always be elevated and often very high.

Adult-onset primary hypothyroidism is usually due to autoimmune disease, unless:

And then …?

If the patient had angina, be very careful indeed. Many clinicians start at 25 µg per day (or even alternate days) and increase every 4–6 weeks. With hypothyroidism or when attempting thyroxine replacement with unstable angina, treat the heart disease first.

Addison’s disease

The clinical presentation and electrolytes indicate adrenal insufficiency. Treatment with glucocorticoids (e.g. hydrocortisone) and IV 0.9% saline is life-saving in this situation and should be started immediately after a blood sample is taken for plasma cortisol/ACTH measurements.

Clinical findings in Addison’s disease

Patients on steroids for surgery

How should the patient’s steroids be continued following surgery?

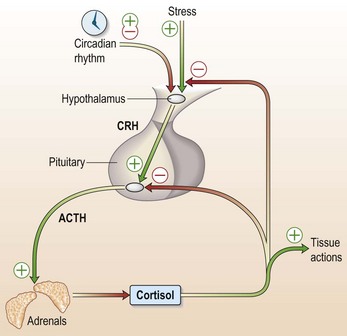

Patients who have been on prednisolone for more than 3 months are likely to have a suppressed pituitary–adrenal axis (Fig. 14.5). Adrenal mineralocorticoid production will be normal, so that the risks of a typical Addisonian crisis are small, but nevertheless this patient will not be able to mount the normal cortisol response to surgery. Glucocorticoid replacement should be given as follows:

An intravenous infusion of hydrocortisone (25–100 mg over 24 h, i.e. 1–4 mg per hour) should be given to all patients who will have a prolonged period NBM or who are on ITU. The pharmacokinetics of hydrocortisone are such that such a continuous infusion of 4 mg will achieve a steady-state plasma cortisol level of > 500 nmol/L, similar to patients on ITU with normal adrenals. A serum cortisol sample after 12 h of infusion can be used to titrate the hydrocortisone infusion down to achieve a cortisol level of 500–750 nmol/L. Hydrocortisone 100 mg every 6 h when given IM will also achieve a similar concentration of cortisol.

Note: Oral hydrocortisone has a greater bioavailability than intravenous hydrocortisone.

Hypercalcaemia

What is the appropriate management of this case with mild hypercalcaemia?

Mild to moderate hypercalcaemia: corrected calcium < 3.00 mmol/L.

Biochemical features of primary hyperparathyroidism

• Elevated PTH in the presence of hypercalcaemia. High normal PTH with hypercalcaemia also suggests hyperparathyroidism because any other cause of hypercalcaemia should suppress the PTH.

• Elevated or high/normal 24-h urinary calcium excretion (normal: 2–8 mmol/24 h).

• Low bicarbonate 15–20 mmol/L (PTH excess causes a mild renal tubular acidosis).

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH) is a benign, familial, autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation of the calcium-sensing receptor in the kidney and parathyroid gland. It is not associated with renal calculi and is asymptomatic. It can be difficult to distinguish from asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism. A low urinary calcium suggests the diagnosis, which is confirmed by examining family members.

Severe hypercalcaemia

Case history

• Recurrence of hyperparathyroidism after surgical cure is unusual and suggests a familial cause of hyperparathyroidism (e.g. multiple endocrine neoplasia) or an alternative cause, e.g. breast cancer.

• Hypercalcaemia causes dehydration by creating a secondary type of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. As calcium clearance is itself dependent on GFR, hypercalcaemia can rapidly decompensate in the presence of fluid depletion.

Management of this patient’s severe hypercalcaemia

This is usually sufficient to bring calcium down to 3.0 mmol/L.

• Bisphosphonate: treatment of choice for hypercalcaemia of malignancies or of undiagnosed cause. 60–90 mg infusion of disodium pamidronate via a cannula in a large vein causes normalisation of serum calcium in 80% of patients after 48 to 72 h.

Other treatments:

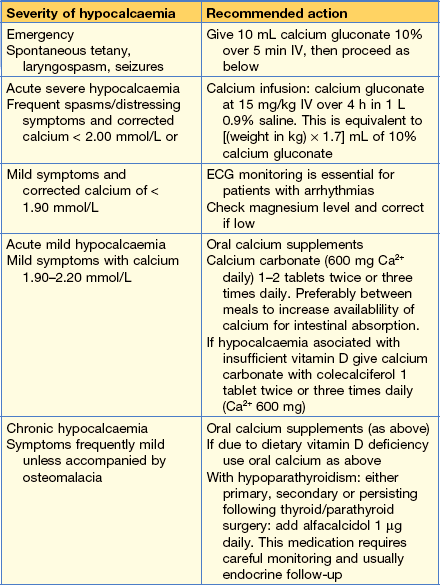

Hypocalcaemia

Clinical features of hypocalcaemia

• Abnormal neurological sensations and neuromuscular excitability

• Numbness around the mouth and paraesthesia of the distal limbs

• Tetany contractions (may include laryngospasm)

• Chvostek’s sign is elicited by tapping the facial nerve just anterior to the ear, causing ipsilateral contraction of the facial muscles (positive in 10% of normals).

• Trousseau’s sign is elicited by inflating a blood pressure cuff for 3 min at the level of systolic blood pressure. This causes mild ischaemia, unmasks latent neuromuscular hyperexcitability and carpal spasm is observed.

How do you assess severity?

Causes of hypocalcaemia

• Hypoparathyroidism (primary, secondary or most commonly post-surgical)

• Renal failure (associated hyperphosphataemia)

• Vitamin D deficiency (giving rickets and osteomalacia)

• Pseudo-hypoparathyroidism (resistance to PTH)

• Severe magnesium deficiency (causes both reduced PTH secretion and resistance to PTH action)

Phaeochromocytoma (catecholamine crisis)

Case history

This history and CT findings would be compatible with a phaeochromocytoma.

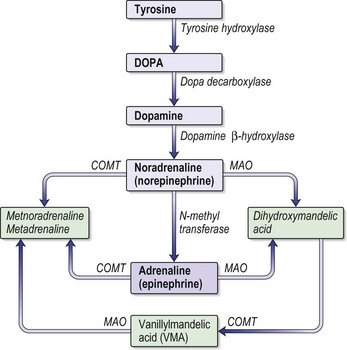

Phaeochromocytoma is known as the 10% tumour (see Information box). It can be diagnosed during routine screening of hypertensive patients (found in only 0.1% of hypertensive subjects), the investigation of unusual episodes or cardiac events of uncertain aetiology. Phaechromocytomas are usually associated with hypertension, ‘attacks’ and/or headache. They secrete adrenaline or noradrenaline (Fig. 14.6).

How do these tumours present?

Symptoms and signs of catecholamine excess include:

• Hypertension (sustained or paroxysmal)

• Palpitations and tachycardia

• Cardiac arrhythmias including atrial and ventricular fibrillation

• Hypertensive crises may be precipitated by intercurrent illness, surgery, or drugs (e.g. beta blockers, tricyclic anti-depressants, metoclopramide and naloxone)

Associations

• Neurofibromatosis type I (neurofibromata, café au lait spots, Lisch nodules (iris hamartomas) and axillary freckling)

• von Hippel–Lindau disease (cerebellar haemangioblastomas, retinal haemangiomas and renal cell carcinoma)

• Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (medullary thyroid carcinoma and hyperparathyroidism)

• Hereditary paraganglioma syndromes (phaeochromocytoma, carotid body tumour).

Diagnostic tests include

• U&Es: potassium often low, urea may be high if dehydrated

• Urinary catecholamines (adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine) are measured by most laboratories. Two sets of normal 24-h urinary catecholamines make a phaechromocytoma very unlikely.

• Plasma (heparinised) catecholamines (adrenaline, noradenaline and dopamine) are specific but not sensitive tests. The blood must be taken directly to the lab for centrifugation.

• MRI/CT scan of the adrenals should be delayed until biochemical diagnosis but are useful in localising the lesion.

• MIBG scan: MIBG (131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine) is taken up selectively by adrenal tissue and is useful for localisation of tumour, particularly in extra-adrenal sites.

How would you manage this case?

• Adequate fluid replacement with 1 L 0.9% saline intially over 1 hour, then 1 L 8-hourly, usually with CVP monitoring.

• Initiate oral alpha blockade: phenoxybenzamine 10 mg × 3 daily increasing gradually to 40 mg × 3 daily.

• When the blood pressure is controlled with phenoxybenzamine and a reflex tachycardia occurs, add propranolol 10–40 mg × 3 daily. Do not use Labetalol.

• Surgery: hypotension commonly occurs intra-operatively when the tumour is removed, and this should be managed with blood, plasma expanders and inotropes as required. Inotropes should be used only when the patient is appropriately fluid replete. Expansion of intravascular volume 12 h before surgery significantly reduces the frequency and severity of postoperative hypotension.

• In emergency (hypertensive crisis) intravenous phentolamine (1–5 mg) should be used, but great care should be taken to adequately rehydrate the patient in order to prevent severe hypotension.

Hypopituitarism

Features of pituitary apoplexy

Pituitary infarction can be silent. Apoplexy implies the presence of symptoms:

• Headache occurs in 75% of cases (may be sudden onset, very severe, or mild)

• Visual disturbance (compression of optic tract, usually causing bitemporal hemianopia)

• Ocular palsy present in 40% of cases: unilateral or bilateral

Clinically, pituitary apoplexy can be very difficult to distinguish from subarachnoid haemorrhage, bacterial meningitis, mid-brain infarction (basilar artery occlusion) and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Assessment of severity

The course of pituitary apoplexy is variable. Headache and mild visual disturbance can develop slowly and persist for several weeks. In the acute form, apoplexy might cause optic nerve compression, haemodynamic instability, coma and is potentially fatal. Neurosurgical advice should always be sought. Residual endocrine disturbance invariably occurs. Panhypopituitarism is the usual result. Table 14.10 shows the replacement therapy that is required.

| Axis | Usual replacement therapies |

|---|---|

| Adrenal | Hydrocortisone 15–40 mg daily (starting dose 10 mg on rising/5 mg lunchtime/5 mg evening) (Normally no need for mineralocorticoid replacement) |

| Thyroid | Levothyroxine 100–150 mcg daily |

| Gonadal | |

| Male | Testosterone IM, orally, transdermally or implant |

| Female | Cyclical oestrogen/progestogen orally or as patch |

| Fertility | HCG plus FSH (purified or recombinant) or pulsatile GnRH to produce testicular development, spermatogenesis or ovulation |

| Growth | Recombinant human growth hormone used routinely to achieve normal growth in children Also advocated for replacement therapy in adults where growth hormone has effects on muscle mass and well-being |

| Thirst | Desmopressin 10–20 mcg 1–3 times daily by nasal spray or orally 100–200 mcg 3 times daily Carbamazepine, thiazides and chlorpropamide are very occasionally used in mild diabetes insipidus |

| Breast (prolactin inhibition) | Dopamine agonist (e.g. cabergoline 500 mcg weekly) |

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; HCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin.

How do patients with hypopituitarism present?

• Patients present at times of stress (e.g. following a general anaesthetic) with hypoglycaemia due to the combination of a lack of GH, cortisol and thyroxine, all of which have a counter-regulatory effect on insulin.

• Post-partum infarction of the gland occurs following post-partum haemorrhage and vascular collapse during a difficult delivery (Sheehan’s syndrome). This diagnosis should be suspected with failure to lactate, amenorrhoea and general ill-health post-partum.

• Other features of hypopituitarism are non-specific and include tiredness, weakness, loss of body hair and loss of libido (sexual interest) and features of hypothyroidism.

• Note that patients with ACTH deficiency have no postural blood pressure drop and normal electrolytes, as adrenal mineralocorticoids (aldosterone) are unaffected.

Investigations of anterior pituitary function

• Baseline blood samples must be taken for cortisol, free thyroid hormone levels, testosterone LH, FSH, prolactin and growth hormone levels.

• Dynamic investigation of pituitary function can be deferred and the patient should be treated expectantly with hydrocortisone (e.g. 10 mg × 2 daily once stable).

• Imaging using CT with fine cuts through the pituitary or MRI is indicated to find any space-occupying lesion.

Diabetes insipidus

This patient probably has transient diabetes insipidus.

How would you manage this patient?

• Ensure adequate access to water or commence IV glucose 5% and 0.18% saline to match urine output if the patient cannot drink enough.

• Make sure an accurate fluid balance chart is being maintained.

• If urine output > 200 mL/hour for 2 consecutive hours, check plasma and urine osmolality.

• DI is confirmed by the presence of a high plasma osmolality (> 290) in the presence of an inappropriately low urine osmolality (< 500 mOsmol/kg).

• Start desmopressin: adult dose 0.5–1.0 µg SC stat followed by 10–40 µg × 3 daily as an intranasal spray.

• If the plasma osmolality is low the patient might be over-drinking due to a dry mouth, and a low urine osmolality is appropriate. In this circumstance, administration of desmopressin will cause a further fall in plasma osmolality and can be dangerous.

Other causes of diabetes insipidus

Diabetes insipidus is either cranial (CDI) or nephrogenic (NDI) due to the inability of ADH to act on the kidney (Table 14.11).

Table 14.11 Cranial and nephrogenic causes of diabetes insipidus

| Cranial DI | Nephrogenic DI |

|---|---|

| Hypothalamic tumour | Drugs: |

| Basal skull fracture | diuretics |

| Neurosarcoidosis | lithium |

| (other hypothalamic disease) | Hypercalcaemia |

| Idiopathic | Hypokalaemia |

| Infection Inflammatory |

Kidney disease e.g. renal tubular acidosis |

| Idiopathic |

Syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH)

Case history

In view of the low plasma osmolality, a spot urine was also sent to the biochemistry department:

Investigation of hyponatraemia

• Take a drug history, e.g. diuretics, SSRIs or carbamazipine.

• U&Es and plasma osmolality: hyponatraemia will be seen.

• Urinary electrolytes and osmolality.

• The patient will have a low plasma osmolality (< 280) and an inappropriately concentrated urine (> 300).

• Free T4 and TSH to exclude hypothyroidism.

• Cortisol and short ACTH test (p. 445) to exclude Addison’s disease.