Endocrinology

PITUITARY DISORDERS

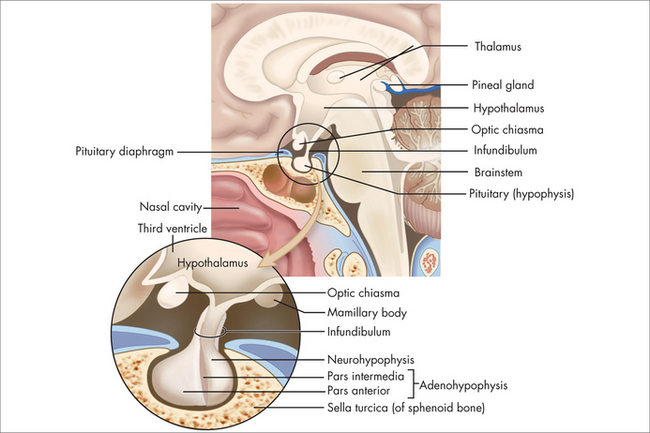

The pituitary normally sits in the sella turcica at the base of the middle cranial fossa (Fig 29.1). It is covered by a dural layer known as the diaphragma sella. The pituitary is joined to the hypothalamus by the infundibulum or pituitary stalk, in front of which sits the optic chiasm. The sella turcica is bounded laterally by the cavernous sinuses and their contents, and the sphenoid sinus antero-inferiorly. The anterior pituitary is embryologically derived from the posterior pharynx and secretes prolactin follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinising hormone (LH), growth hormone (GH), thyrotropin-stimulating hormone (TSH) and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) in response to trophic-releasing hormones from the hypothalamus via a portal blood flow system. The posterior pituitary secretes oxytocin and vasopressin under neural control from the hypothalamus.

PITUITARY TUMOUR

Tumours in the pituitary are common and have been found to occur in around 10% of people in autopsy studies.1 Various series have reported rates of up to 24%. With the high background rate of pituitary masses seen on MRI, clinical questions about how to proceed are likely to occur. Unless the brain is imaged for another reason, it is more prudent to have a clinical diagnosis and confirmatory tests of a pituitary disorder before requesting a CT or MRI of the pituitary.

Aetiology

Diagnostic approach

Prolactinomas tend to produce prolactin in a linear relation to their size. Macroadenomas therefore tend to produce levels of prolactin greater than 10 times the upper limit of the reference range. Microadenomas tend to produce levels of prolactin from 1–10 times the upper limit of normal. Other causes of prolactin in this range include medications with a dopamine antagonistic effect, such as antipsychotics and antiemetics. Stress may cause a transient increase in prolactin, as will physical causes such as nipple stimulation and lesions that affect the T4 dermatome, including Varicella zoster. Masses that result in compression or loss of function of the pituitary stalk also limit the inhibitory signals from the hypothalamus and result in microadenoma-level hyperprolactinaemia.

Examination

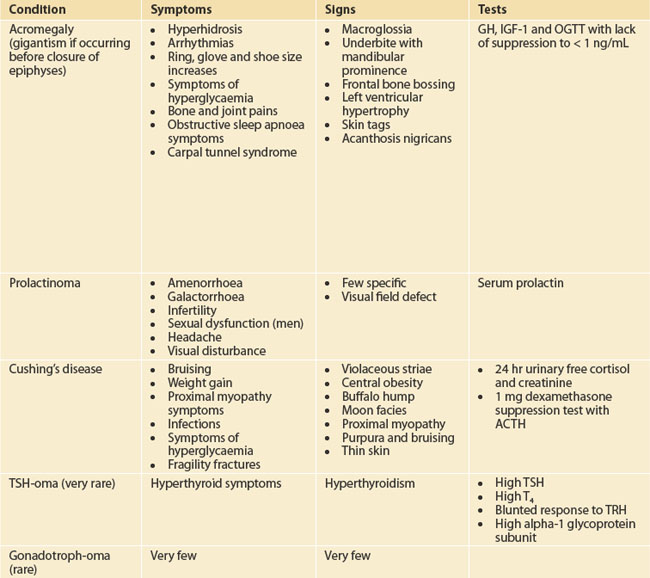

Target the examination to the symptoms and manifestations of hormone excesses or deficiencies as outlined in Table 29.1. Check for galactorrhoea as well as back and skin lesions in patients suspected with hyperprolactinaemia. Galactorrhoea from one breast in the absence of hyperprolactinaemia requires careful examination to ensure that there is no local breast pathology. Always check visual fields to confrontation.

ACROMEGALY

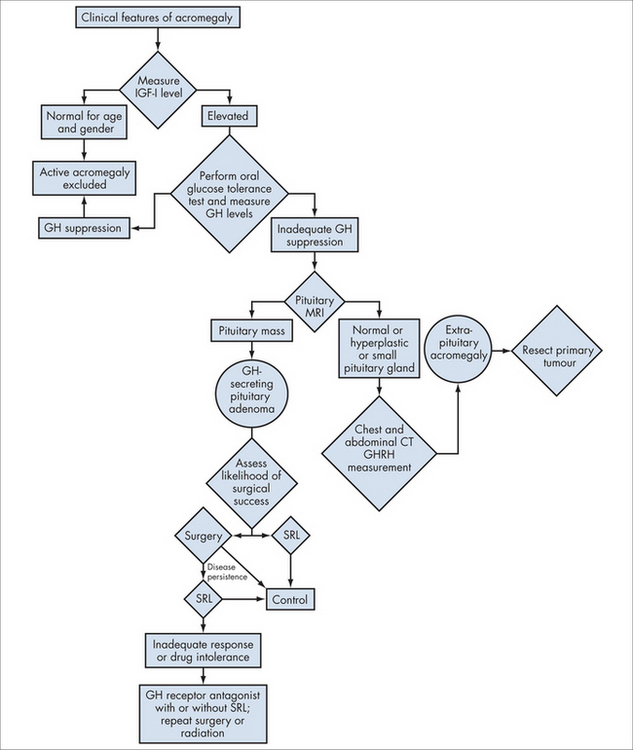

Acromegaly is a condition of monoclonal growth of pituitary somatotrophs that produces excess growth hormone in a non-regulated way. It has a prevalence of around three per million.2

Investigations

Integrated management

HYPOPITUITARISM

Hypopituitarism may be complete (pan-) or partial. It may be congenital, acquired or iatrogenic.

Acquired hypopituitarism may occur due to problems such as trauma affecting the pituitary stalk (infundibulum), apoplexy or infarction in Sheehan’s syndrome. Other issues such as lymphocytic hypophysitis are being increasingly recognised with higher-teslar MRI machines. Infections and inflammatory lesions such as sarcoid and histiocytosis may affect the pituitary, as well as intra- and extrasellar masses.

Lastly, hypopituitarism can be secondary to hypothalamic disease.

Diagnostic approach

Screening for hypopituitarism should be thought of in those with developmental problems such as:

or those with:

or those who have had pituitary surgery or cranial radiation.

Special tests

Integrated management

Pharmacological

Many of the deficiencies of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis are life threatening. Replacement of glucocorticoids, if these are thought to be deficient, should be done prior to thyroxine replacement and would generally be instigated by an endocrinologist and in hospital. If a patient is in a critical condition, then 200 mg of IV hydrocortisone should be given. Otherwise 100 mg of IV hydrocortisone with 50 mg q6h can be started and blood tests awaited. Maintenance doses of glucocorticoids are not fully elucidated but hydrocortisone equivalent 20–30 mg given in 2–3 divided doses, or cortisone acetate at 25–37.5 mg per day in two divided doses for adults, is a good place to start. The goal is to very slowly and carefully titrate down to the lowest dose that keeps the patient well. Thyroxine may then be replaced if necessary at a dose of 1.6 μg/kg.

PARATHYROID DISORDERS

HYPERCALCAEMIA

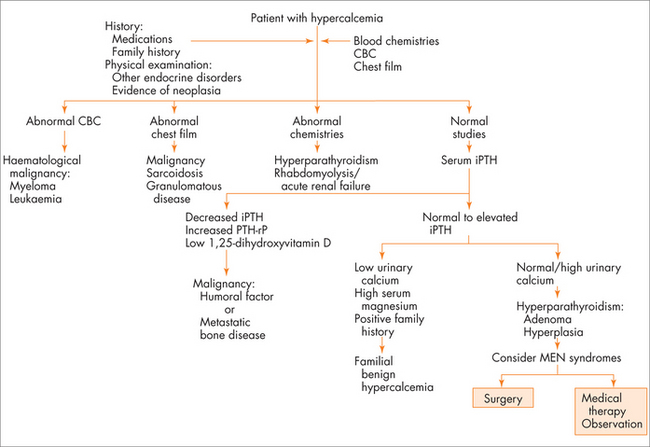

The most common symptoms of hypercalcaemia are the classic ‘stones, bones, moans and groans’ of kidney stones, bone pains, mood changes including depressive symptoms and abdominal pains including constipation. Polyuria and dehydration can occur secondary to high serum calcium. The most common cause for congenital hypercalcaemia is familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia. The most common acquired causes of hypercalcaemia are hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. A useful thought map to think about acquired hypercalcaemia is to think about PTH-dependent and PTH-independent causes of hypercalcaemia (see Fig 29.3).

Aetiology

Milk–alkali syndrome is less common now that histamine receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are the mainstay treatment of hyperacidity syndromes of the stomach. The use of antacids together with the ingestion of milk products results in increased absorption and mild hypercalcaemia. While there has been a reduction in the presentation of milk–alkali syndrome from these less-used drugs, there have been a number of case reports of similar presentations in those using large doses of calcium carbonate, which provides both calcium and alkali. High calcium level together with high bicarbonate and perhaps some renal impairment should prompt the GP to ask about calcium carbonate intake.

Other causes such as multiple myeloma and breast cancer are the two more common malignancies that can lead to lytic bone lesions and uncontrolled release of calcium into the extracellular fluid, independently of a suppressed PTH level.

History

Examination

Investigations

HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

Hyperparathyroidism can be primary, secondary or tertiary.

History

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism should be evident with a patient who has chronic kidney disease being managed by a renal physician. Treatment and management of this condition should be discussed with that specialist physician.

Integrative management

Surgical

In primary hyperparathyroidism, the newer imaging techniques and newer surgical approaches have meant that, for experienced surgeons, the parathyroid adenoma that has been identified pre-surgery may be excised through a limited neck dissection. If surgery is not indicated or not chosen, then good hydration and maintaining 25-OH Vit D > 50 nmol/L should be pursued. Cinacalcet is currently indicated for parathyroid carcinoma, and secondary hyperparathyroidism of renal disease with hypercalcaemia. It may be possible to consider the use of Cinacalcet in non-surgical PHPTH patients.

HYPOPARATHYROIDISM

Pathology

Integrative management

Pharmacological

PARATHYROID TUMOUR

Parathyroid adenoma and carcinoma are difficult to differentiate clinically. Parathyroid carcinoma is an uncommon but important condition occurring in around 2% of investigated hyperparathyroidism. With a different prognosis and natural history, it is important to identify. Typically, parathyroid carcinomas tend to cause higher levels of hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcaemia than primary hyperparathyroidism.

Investigations

Pathology

The first step is to confirm the extent of the hypercalcaemia and establish that it is PTH-dependent hypercalcaemia. Use the flow diagram and work-up algorithm in Fig 29.3 (in the section on hypercalcaemia).

Integrative management

Pharmacological

There is little data on adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy for parathyroid carcinoma.

Ongoing review and/or monitoring

Patients should have their calcium, PTH and vitamin D levels checked every 6 months, unless earlier is clinically indicated. With a high rate of recurrence, and increased possibility of transformation of normal parathyroid tissue to parathyroid carcinoma in those who carry the HRPT gene mutation, recurrence may be detected early.

THYROID DISORDERS

HYPERTHYROID DISORDERS

Subacute (de Quervain’s) thyroiditis

In subacute thyroiditis there is inflammation of the thyroid, often post viral infection, which typically results in symptoms of hyperthyroidism and a painful neck. The thyroid will be tender to palpation. This condition may be transient and follow a viral illness such as a common cold, and tends to settle down over several weeks. Analgesia is commonly required. Steroids may be used if aspirin or anti-inflammatory medications are not effective. Beta-blockers may be used to treat the symptoms of hyperthyroidism if they are significant. The condition tends to resolve spontaneously over a few weeks to months, and may be followed by a short period of hypothyroidism, as it recovers and reverts to normal.

THYROID DISEASE: SUMMARY OF THERAPEUTICS

ADRENAL GLAND DISORDERS

ADDISON’S SYNDROME

Adrenal insufficiency is an important treatable condition, and can be life-threatening if not identified and treated properly. The incidence varies between developed and developing countries, due to the higher incidence of infective diseases affecting the adrenal gland, in the latter—it is estimated at 1 in 100,000 in developed countries and up to 11 per 100,000 in developing countries, and is likely to increase in the latter in line with the incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis disease and HIV/AIDS.

Aetiology

Other congenital causes of adrenal insufficiency such as adrenoleukodystrophy are more rare.

Infiltration from amyloid or metastatic breast or lung cancer is also rare.

Diagnostic approach

ACTH is released in a peak and is relatively unstable if not collected properly, but, those issues aside, a low cortisol with a low or inappropriately normal ACTH would tend to point to secondary adrenal insufficiency. A high ACTH at any time of the day with a less than adequate cortisol is very indicative of primary adrenal problems. In the indeterminate range, a short synacthen test of 250 μg of synacthen given as an intramuscular injection with cortisol measured at 0, 30 and 60 minutes can be performed. If done at 0800 with a morning ACTH and cortisol, a basal result of > 400 nmol/L or a stimulated rise of about 550 nmol/L indicates adequate adrenal function. Check with your local laboratory as to the normal cut-offs for its particular assay. The short synacthen test does not differentiate between primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency in the chronic setting, where there is inadequate ACTH drive with resulting adrenal atrophy and blunting of adrenal response, as one would see in primary disease.

Integrative management

Pharmacological

In chronic adrenal insufficiency, replacement regimens are many but the aim is to try to provide enough glucocorticoid replacement in a normal physiological pattern that follows a diurnal variation, with a peak early in the morning that then tapers through the day. This may be achieved with hydrocortisone 20–30 mg per day in 2–3 divided doses in a regimen such as 12 mg on waking, 8 mg at lunch and 4 mg at afternoon tea. A simpler strategy is hydrocortisone 20 mg mane and 10 mg in the early afternoon, or cortisone acetate 25 mg mane and 12.5 mg in the early afternoon. The afternoon dose may be brought closer to midday if the patient reports difficulty sleeping. If the patient reports feeling unwell and quite fatigued in the early evening, then using a three-times-a-day split dose with a smaller proportion in the late afternoon can be trialled.

Paramedical

CUSHING’S SYNDROME

Cushing’s disease is the disorder described by Harvey Cushing, with pituitary disease with ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism. Cushing’s syndrome describes the other forms of cortisol excess. (See Table 28.3 for a list of other causes of hypercortisolaemia.) The incidence of Cushing’s disease or syndrome is difficult to quantify. There is significant overlap between the manifestation of Cushing’s disease, and that of obesity and its complications. European series have estimated the incidence at 1–3 per million patients.

| Name | Cause |

|---|---|

| Cushing’s disease | ACTH-dependent pituitary disease |

| Pseudocushing’s disease |

The diagnosis may be perplexing, given that there is much overlap between normal levels in biochemical testing and levels in those with true glucocorticoid excess.

Pathology

Excessive cortisol has many effects:

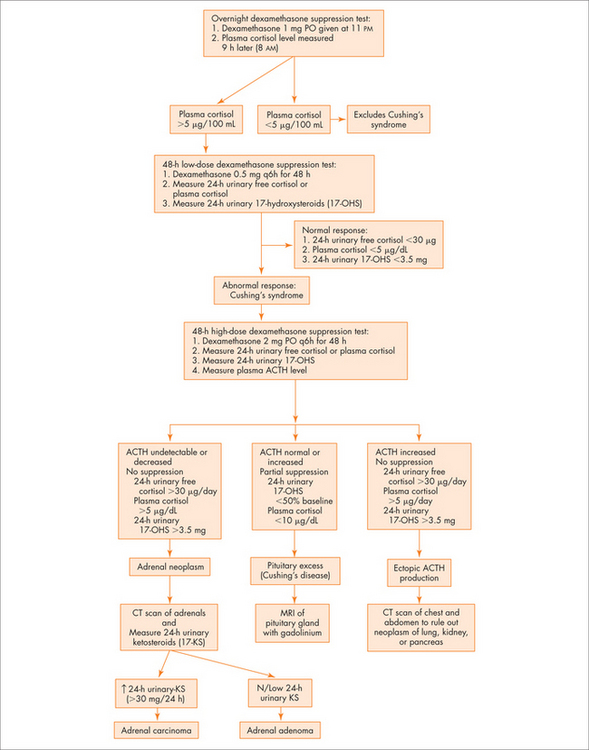

Diagnostic approach

Question 2: Is there glucocorticoid excess?

The Endocrine Society has released guidelines for investigation of Cushing’s Syndrome and Cushing’s disease.3

See Figure 29.4 for an overview.

Question 3: Is the cortisol excess ACTH dependent?

History

Clinical suspicion may be increased and testing performed in those with:

Integrative management

Active surveillance

Pharmacological

Medical therapies are aimed at the two different parts of the problem.

Surgical

1 Molitch ME, Russell EJ. The pituitary ‘Incidentaloma’. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112(12):925-931.

2 Holdaway IM, Rajasoorya C. Epidemiology of acromegaly. Pituitary. 1999;2:29-41.

3 Endocrine Society. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society practice guideline. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.