17 Endocrine tumours

Thyroid cancer

Evaluation

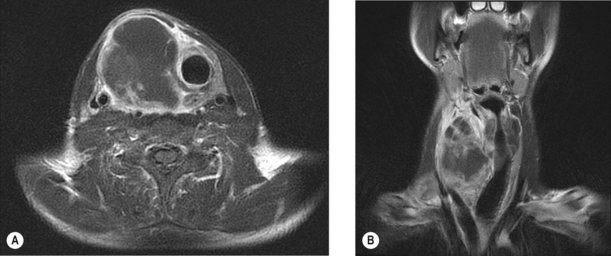

Evaluation includes clinical examination and assessment for thyrotoxicosis which is rare in cancer. Initial investigations include thyroid function tests and FNA of the lesion. Biopsy may be indicated for lymphoma and anaplastic carcinoma and hemithyroidectomy is indicated for all follicular lesions. MRI is the preferred imaging to assess local invasion (Figure 17.1) as the use of iodine containing contrast can cause thyroid stunning which may prevent effective use of radioiodine for at least three months subsequently.

Staging

Box 17.1 shows the TNM staging system. The TNM and MACIS (Box 17.2) have been shown to be the best predictors of outcome in differentiated thyroid cancer.

Box 17.1

TNM staging in thyroid cancer

T stage

| pT1 | Tumour ≤2 cm in greatest dimension |

| pT2 | Intrathyroidal tumour >2–4 cm in greatest dimension |

| pT3 | Intrathyroidal tumour >4 cm in greatest dimension |

| pT4 | Tumour beyond the thyroid capsule |

N stage (cervical and upper mediastinal)

| N0 | No nodes involved |

| N1 | Regional nodal involvement |

| N1a Ipsilateral cervical nodes | |

| N1b Bilateral, midline or contralateral cervical nodes, or mediastinal nodes |

Distant metastases

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

| MX | Distant metastases cannot be assessed |

Management

Well-differentiated cancer

Surgery is the definitive treatment of all malignancies except lymphoma. The majority of patients need total or near total thyroidectomy. In low-risk patients (<1 cm papillary cancer with no nodes, <2 cm follicular cancer in women aged less than 45 years and <1 cm follicular cancer with minimal capsular invasion) lobectomy is adequate. Patients with high-risk disease (male >45 years, tumour >4 cm and extracapsular spread) are at risk of level VI nodal involvement and hence elective central node dissection is indicated. Patients with proven neck node metastases are treated with modified radical neck dissection. All patients should have serum calcium postoperatively to rule out transient hypocalcaemia. Serum thyroglobulin (TG), the tumour marker, is estimated 6 weeks postoperatively which should be undetectable in patients who had total thyroidectomy and have no residual disease. Patients after total thyroidectomy are started on triiodothyronine (T3) 20 mg thrice daily which is subsequently changed to T4. T4 is started with a dose of 100 mcg daily and increased by 25 mcg every 6 weeks until TSH levels are below 0.1 MiU/L.

Radioablation

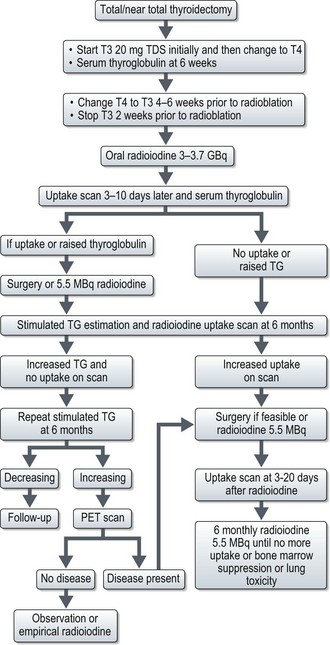

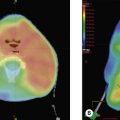

Postoperative radioiodine ablation is recommended for all patients except for those who had total thyroidectomy for a well-differentiated unifocal tumour of <1 cm with no vascular or extracapsular invasion. Informed consent should be obtained and instruct female patients not to get pregnant prior to and up to 12 months after treatment (Box 17.3). T4 is substituted with T3 4–6 weeks before radioablation and T3 is withdrawn 2 weeks before ablation. 3–3.7 GBq of radioiodine is administered orally. In patients with a history of myxoedema psychosis, severe cardiac disease and high volume disease, T3 withdrawal can be dangerous and hence recombinant human TSH (0.9 mg IM daily for 48 hours before radioablation) is used. Patients are admitted to and remain in a specialist facility with appropriate shielding and sanitation. Isolation is continued until safe levels of radiation are measured by a medical physicist. Patients are advised to keep well-hydrated, empty the bladder frequently and to take prescribed laxatives to avoid constipation and these measures are aimed at minimizing the absorbed dose of radiation. An uptake scan is done 3–10 days after radioiodine to assess residual thyroid tissue. In patients with elevated TG and positive uptake scans, either further surgery or repeat dose of radioiodine (5.5 MBq) is indicated. Further management afterwards is shown in Figure 17.2.

Medullary carcinoma

There is no role for radioiodine ablation. In patients with incomplete resection, postoperative radiotherapy to the thyroid bed, bilateral cervical and upper mediastinal nodes (50–60 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction) may be given to improve relapse-free survival.

Adrenocortical carcinoma

Diagnosis

Initial investigations include hormonal workup and imaging with CT chest and abdomen (Figure 17.3). MRI is also useful in identifying invasion of adjacent organs and the inferior vena cava, and hence in planning surgery. Biopsy of an adrenal tumour is controversial because of the theoretical risk of needle tract metastases. However, it may be acceptable if primary surgical management is not feasible and diagnosis cannot be established with non-invasive measures.

2007 British Thyroid Association – Guidelines from the management of thyroid cancer 2nd Edition. Available from http://www.british-thyroid-association.org/, 2007.

Ganti AK, Cohen EE. Iodine-refractory thyroid carcinoma. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2006;1:133-141.

Tuttle RM, Ball DW, Byrd D, et al. Medullary carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:512-530.

Sherman SI. Molecularly targeted therapies for thyroid cancers. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:605-611.

Neff RL, Farrar WB, Kloos RT, Burman KD. Anaplastic thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:525-538.

Wandoloski M, Bussey KJ, Demeure MJ. Adrenocortical cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(5):1255-1267.

Fassnacht M, Allolio B. Clinical management of adrenocortical carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:273-289.