Endocrine System

The endocrine system consists of a number of organized glands, groups of cells, and dispersed solitary cells that control the functional balance of internal organs by means of chemical messengers called hormones. Organized endocrine glands include the pituitary, the thyroid and parathyroid, the adrenal cortex and medulla, and the endocrine pancreas. In addition, sex organs such as the ovary and testis produce certain hormones (see chapters 7 and 8).

Endocrine Pancreas

TABLE 12-1

PRIMARY INFLAMMATION OF THE THYROID GLAND (THYROIDITIS)

| Entity | Pathology | Pathogenesis |

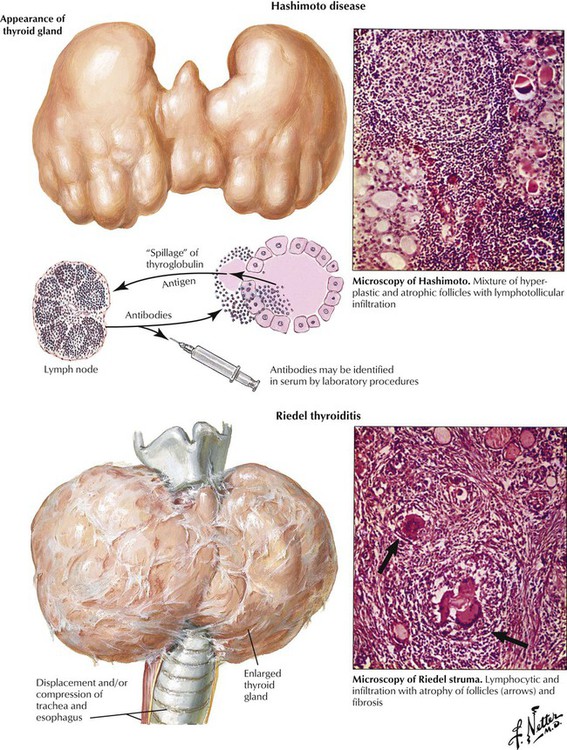

| Lymphofollicular thyroiditis (Hashimoto thyroiditis), chronic | Lymphocytic/plasmacellular infiltrate with lymph follicles, follicle destruction, oxyphilic metaplasia of follicle cells (Hürthle or Askanazy cells) | T-cell autoimmune reaction (TPO, TMA), genetic predisposition |

| Granulomatous thyroiditis (de Quervain thyroiditis), subacute | Microfocal neutrophilic infiltrates, follicle destruction with secondary giant cell granulomatous reaction, marked lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates | E.g., virus infection: coxsackie, adenovirus, mumps, and others, secondarily autoimmune |

| Chronic sclerosing thyroiditis (Riedel thyroiditis) | Lymphocytic thyroiditis with progressive glandular atrophy and fibrosis extending to adjacent tissues | Suggestively autoimmune* |

| Painless subacute thyroiditis | Lymphocytic infiltrates with eventual follicular destruction, usually self-limited, hyperthyroid | Unknown HLA-DR3 associated |

TMA indicates thyroid microsomal antigen; TPO, thyroid peroxidase antigen.

TABLE 12-2

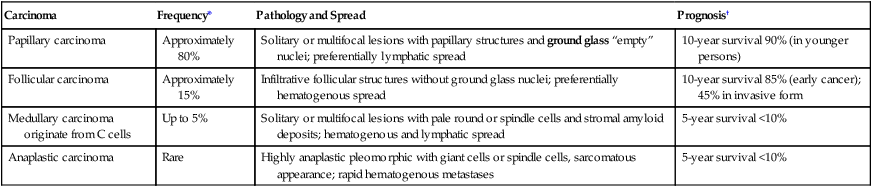

| Carcinoma | Frequency* | Pathology and Spread | Prognosis† |

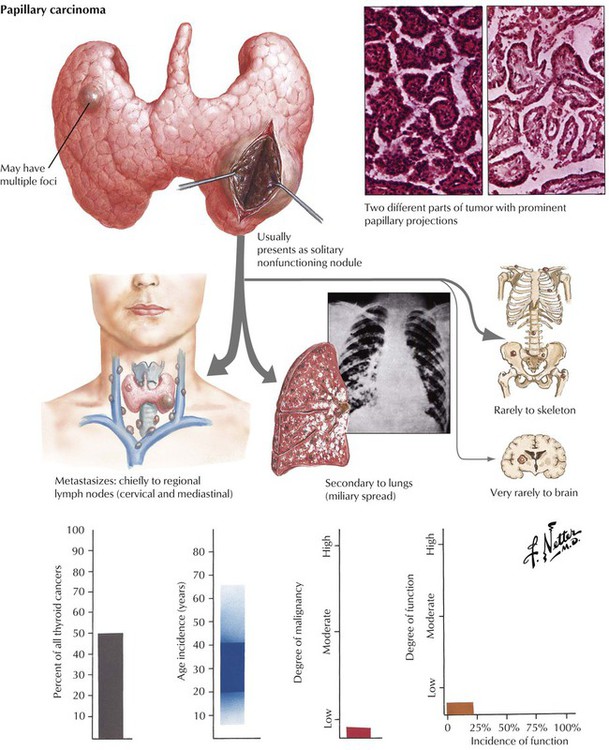

| Papillary carcinoma | Approximately 80% | Solitary or multifocal lesions with papillary structures and ground glass “empty” nuclei; preferentially lymphatic spread | 10-year survival 90% (in younger persons) |

| Follicular carcinoma | Approximately 15% | Infiltrative follicular structures without ground glass nuclei; preferentially hematogenous spread | 10-year survival 85% (early cancer); 45% in invasive form |

| Medullary carcinoma originate from C cells | Up to 5% | Solitary or multifocal lesions with pale round or spindle cells and stromal amyloid deposits; hematogenous and lymphatic spread | 5-year survival <10% |

| Anaplastic carcinoma | Rare | Highly anaplastic pleomorphic with giant cells or spindle cells, sarcomatous appearance; rapid hematogenous metastases | 5-year survival <10% |

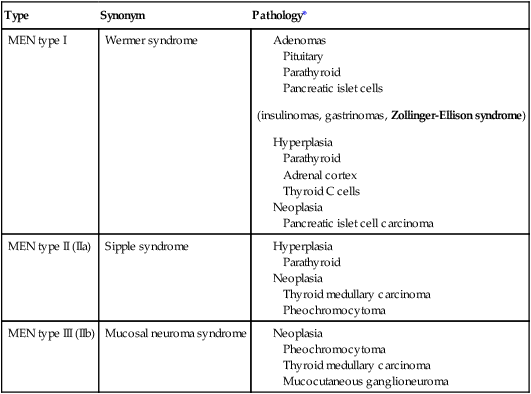

TABLE 12-3

CLASSIFICATION OF MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA

| Type | Synonym | Pathology* |

| MEN type I | Wermer syndrome |

MEN indicates multiple endocrine neoplasia.

*With some selectivity in individual patients.

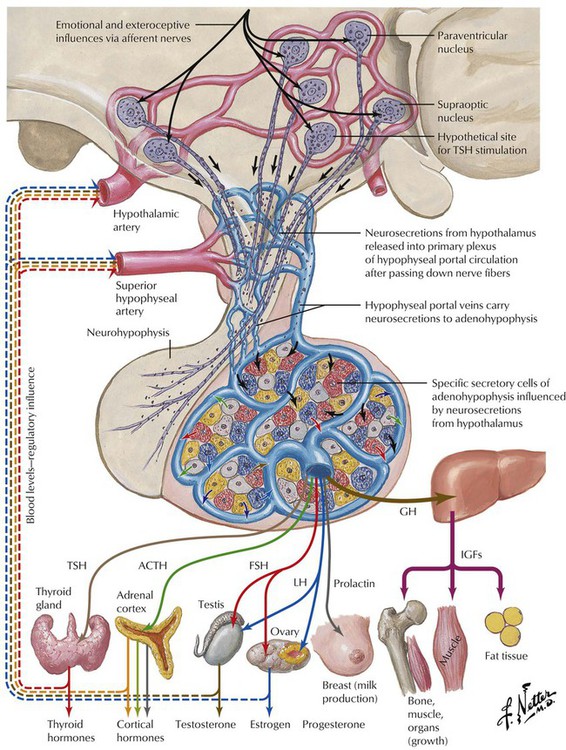

Endocrine function is supervised by the nervous system, especially the hypothalamus. Several nuclei of the hypothalamus secrete hypothalamic hormones that stimulate peripheral endocrine tissues via the pituitary (hypophysis). These hormones include corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), and growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH). In addition, there are several direct- and indirect-acting hypothalamic hormones, including arginine vasopressin (AVP), somatostatin, and dopamine. Hypothalamic function responds to extraneous physical and emotional stimuli as well as to internal feedback control.

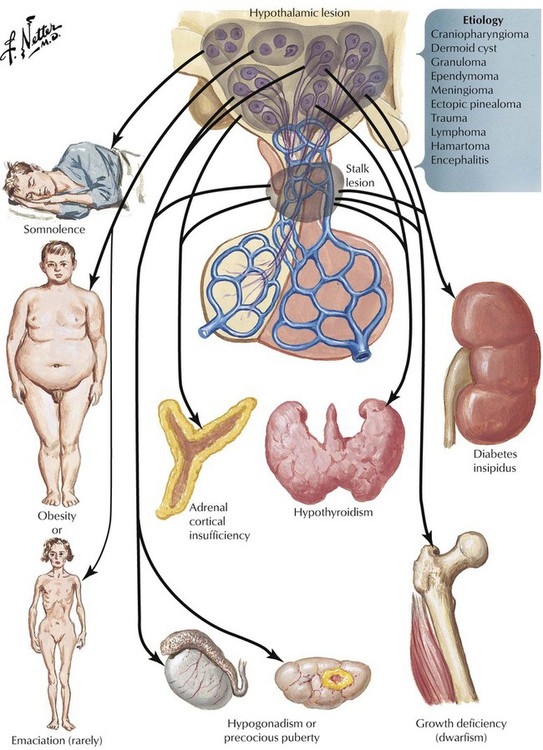

The pituitary gland controls the functional activity of peripheral endocrine tissues by secreting a large number of hormones, including thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), interstitial cell–stimulating hormone (ICSH), luteotropic hormone or prolactin (LTH), somatotropic hormone (STH), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH). Hypothalamic damage from viral or other infections, granulomatous diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis), degenerative disorders, or tumor metastases has pathologic effects on the function of other peripheral tissues and endocrine organs. Such relations exist in obesity or anorexia nervosa, hypogonadism (e.g., pubertas tarda, sterility, amenorrhea), and certain rare polysymptomatic syndromes (Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome, Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl syndrome).

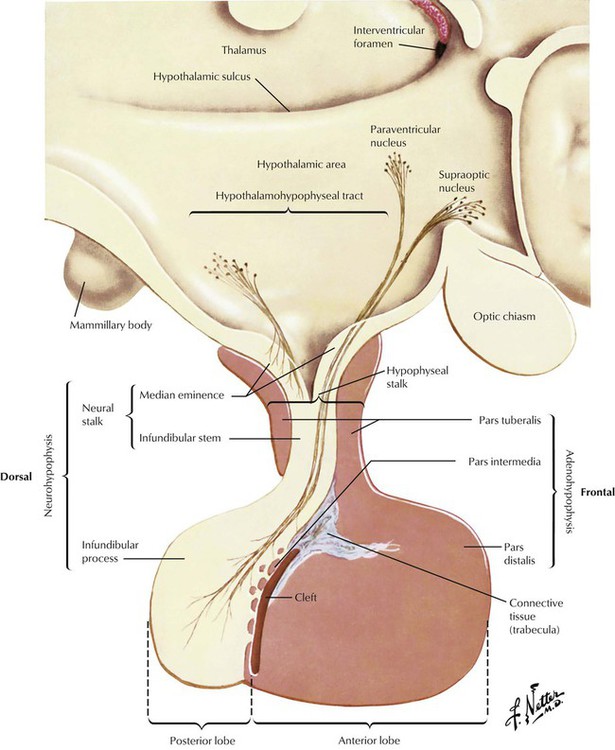

The pituitary gland consists of an anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) and a posterior lobe (neurohypophysis), which has a stalk that connects the organ to the infundibulum hypothalami. The anterior lobe develops from an ectodermal outgrowth of the oral cavity, whereas the posterior lobe with the stalk represents a downward extension of the brain. The neurohypophysis (posterior lobe) serves as a reservoir for AVP (antidiuretic hormone [ADH]) and oxytocin, both of which are secreted from the hypothalamus by unmyelinated nerve endings. The adenohypophysis, which composes approximately 80% of the organ, is the major hormone-producing part of the pituitary gland. The epithelial cells of the adenohypophysis are classified as acidophilic, basophilic, and chromophobe cells, depending on their hormonal functions.

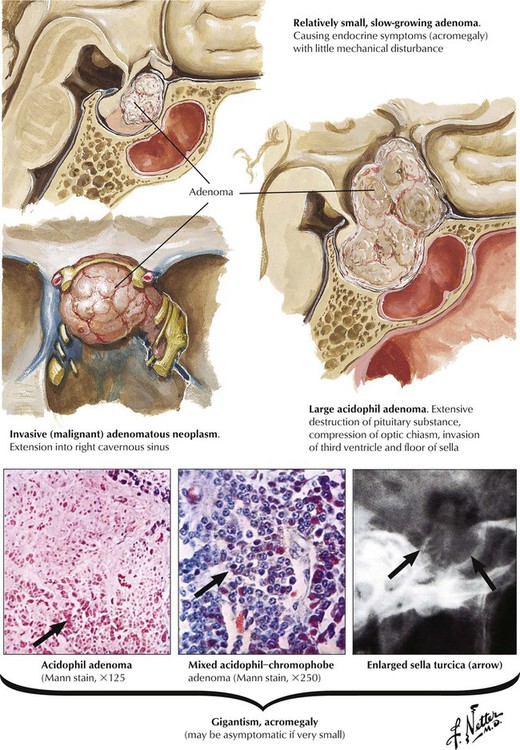

Acidophilic or chromophobe adenomas may secrete excessive somatotropin (growth hormone [GH]), which produces gigantism in prepubertal children or acromegaly in postpubertal individuals. Exposure to excessive GH before epiphyseal closure leads to symmetric giant growth. After symphyseal fusion, excessive GH causes asymmetrical growth affecting the nose, the chin, the hands, and the toes. Persons with acromegaly show hyperostosis, cardiomegaly and visceromegaly, thickened skin, and other endocrine abnormalities. Clinical features include arthralgia, muscle weakness, neuropathy, and hypertension in approximately one third of patients. Patients are at high risk for cardiovascular and respiratory failure and cerebrovascular death unless the adenoma is removed by surgery or radiation.

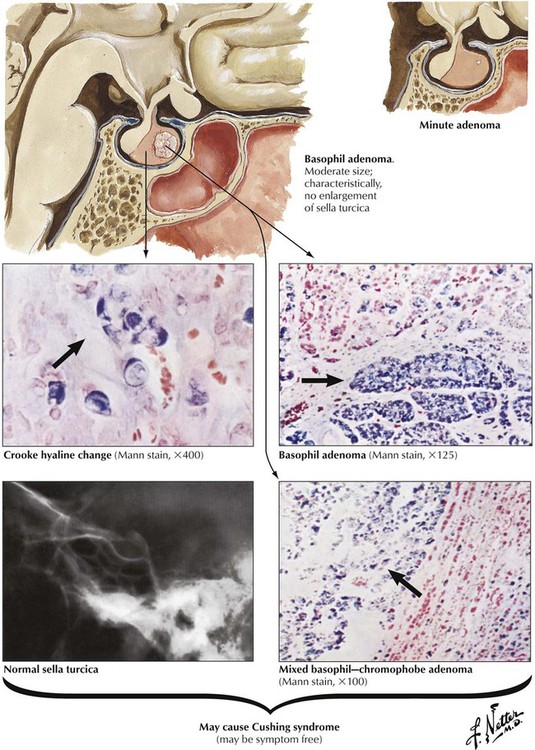

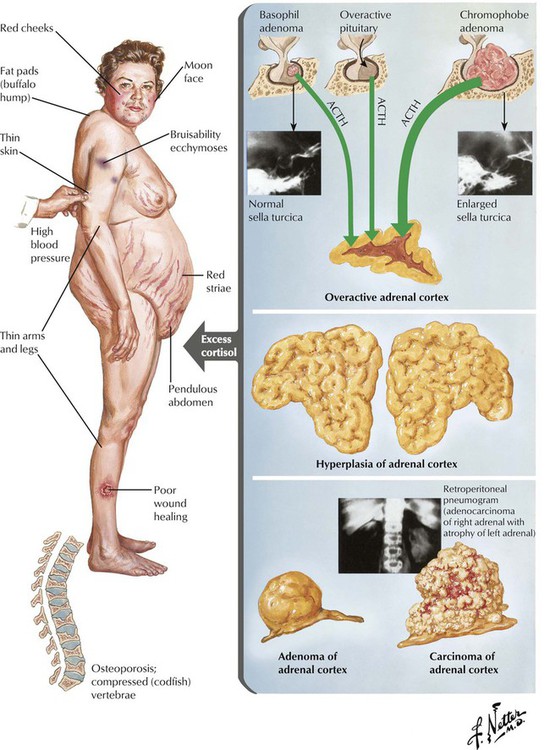

Basophil adenomas are uncommon, usually small, and located within the normal-sized gland. They may secrete corticotropins (corticotropic adenoma) or related peptides, such as lipotropin and endorphins. Crooke hyaline, homogeneous hyaline globules consisting of densely packed, keratin-positive paranuclear intermediate filaments, is characteristic of basophil adenomas. Crooke hyaline is seen when Cushing disease is caused by primary adrenal tumors or in prolonged corticotropin therapy. Clinical features of functioning corticotropic adenomas are described as Cushing syndrome: truncal obesity with moon facies, systemic hypertension, muscle weakness (decreased muscle mass), hyperglycemia, and thirst. Osteoporosis, hirsutism (male-type hair distribution in females) and amenorrhea, mood swings, and depression are also characteristic. The diagnosis is further confirmed by elevated free cortisol in the 24-hour urine.

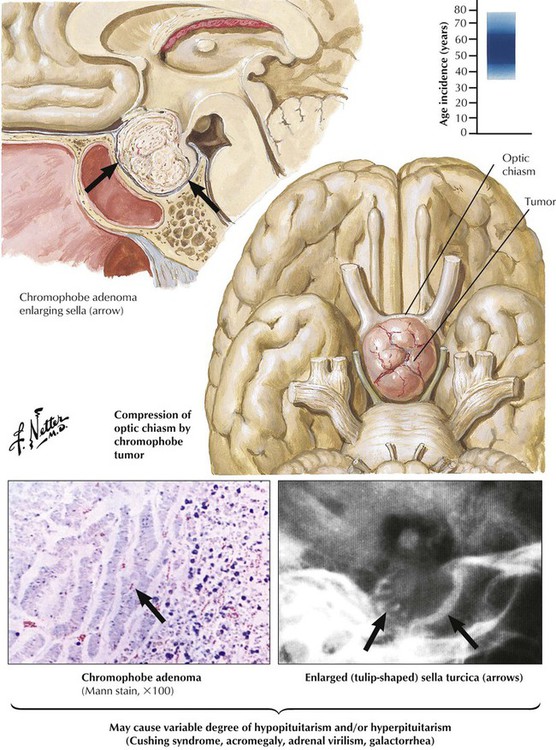

Chromophobe adenomas, the most common pituitary tumors, constitute approximately 15% of all intracranial tumors. They occur in both sexes, usually in later life (sixth decade). Chromophobe adenomas, which may remain microscopic for long periods, most often compress the optic chiasm, causing subsequent bitemporal hemianopsia when they expand. Vision impairment is often the initial clinical sign. Functioning chromophobe adenomas produce a variety of hormones, including prolactin (lactotrophic adenomas), somatotropin (somatotropic adenomas), LH and FSH (gonadotropic adenomas), and, rarely, TSH (thyrotropic adenomas). Clinical features differ according to adenoma type with signs of hypogonadism and virilization, acromegaly, hypothyroidism, and others. Some adenomas produce more than 1 hormone including corticotropins.

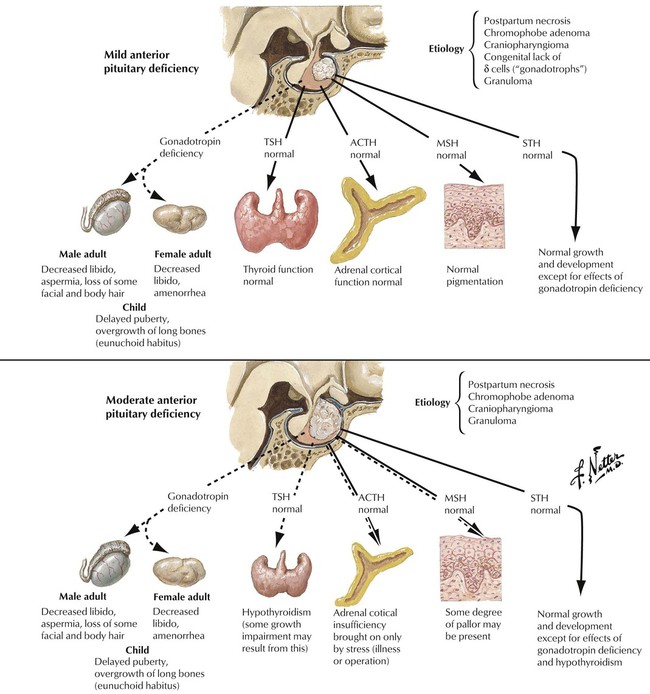

Hypopituitarism refers to deficiencies in hormone production by the adenohypophysis (anterior lobe of pituitary) The lack of hormone affects the function of peripheral endocrine tissues. Hypopituitarism is caused by destruction of the gland by tumor metastases, local tumors extending into the sella turcica, infiltrative processes such as infections (e.g., tuberculosis), metabolic disorders (e.g., hemochromatosis, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease), ischemic postpartum necrosis (Sheehan syndrome), hemorrhagic infarction (pituitary apoplexy), or, rarely, hypophyseal atrophy secondary to subarachnoid space herniation (empty sella syndrome). Symptoms develop slowly and occur when approximately 75% of the adenohypophysis is lost. Hormone replacement is the therapy of choice. The underlying disease causing the hypopituitarism determines the prognosis.

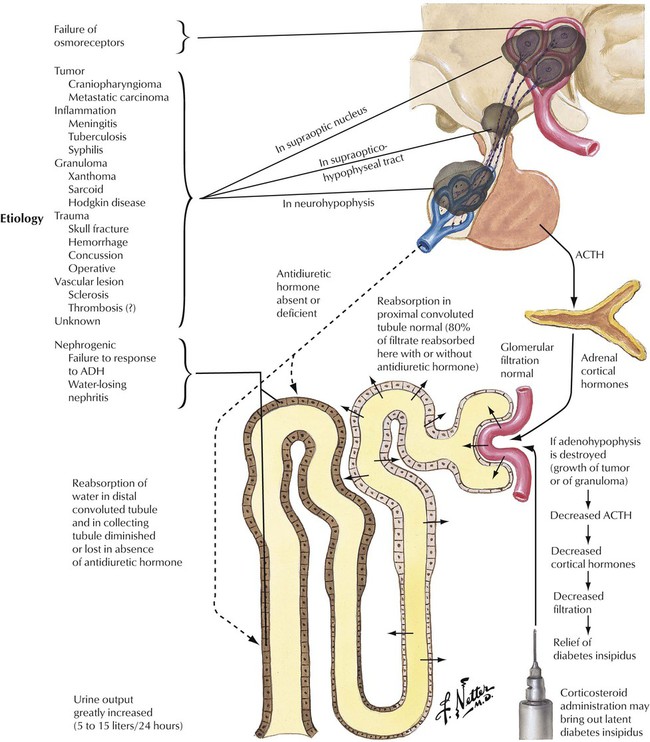

Deficient hormone release by the neurohypophysis (posterior lobe of pituitary) results in inadequate ADH availability. Diabetes insipidus, characterized by uncontrolled water diuresis, polyuria, and polydipsia (excessive thirst), ensues. Although patients consume large amounts of water daily, they may experience life-threatening dehydration. Diabetes insipidus is caused by a variety of processes (head trauma, infection, neoplasm), but many cases develop without recognizable underlying disease. Craniopharyngioma, a dysontogenetic tumor derived from displaced epithelium of the Rathke pouch, is one of the more common tumors that compresses and destroys the neurohypophysis.

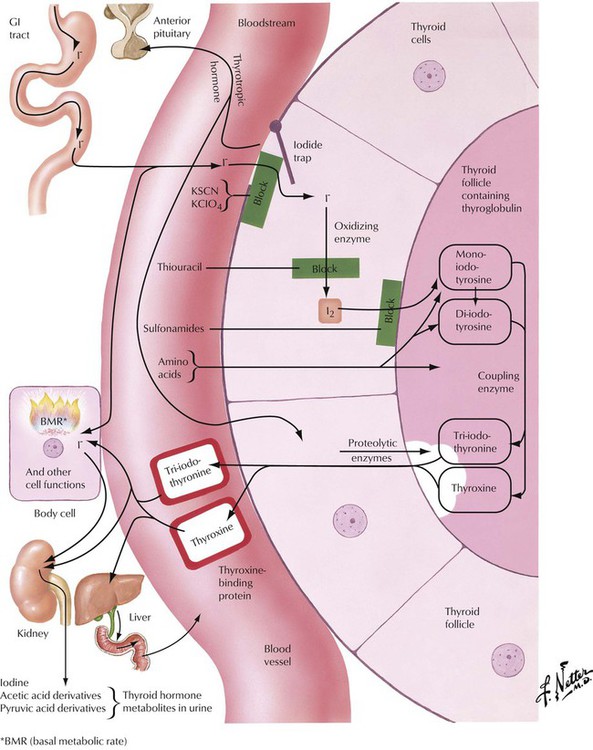

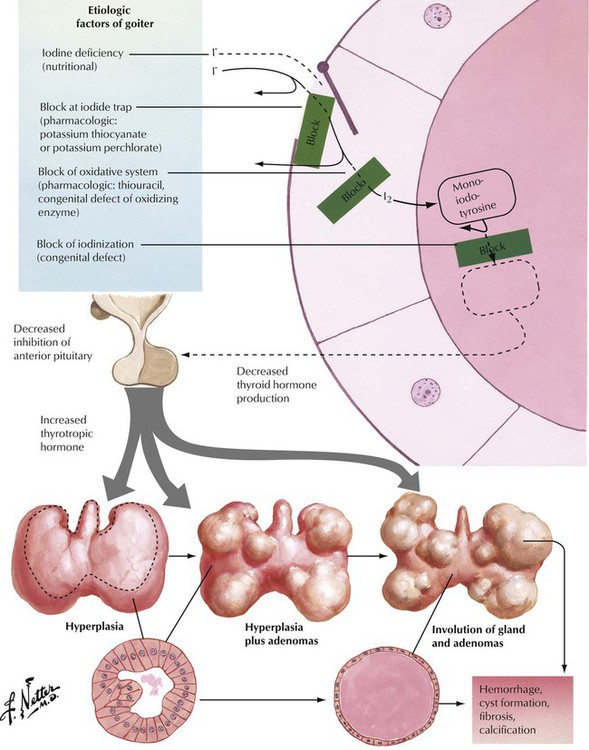

In the thyroid follicular epithelial cells, iodide, which is absorbed in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is oxidized to I2, which serves for the stepwise iodination of tyrosine. The combination of 2 molecules of diiodotyrosine produces T4 (l-thyroxin). The coupling of 1 molecule of monoiodotyrosine to 1 molecule of diiodotyrosine results in T3. T4 and T3 are the main thyroid hormones. They are coupled to thyroglobulin and are stored in follicular colloids. Proteolytic enzymes release T4 and T3 into the circulation as active hormones when stimulated. Proteolysis, the follicular epithelial resorption and release of the hormone by these cells, is accompanied morphologically by such signs of follicular activation as paraepithelial resorptive vacuoles in the colloid and epithelial swelling (cuboidal size) and proliferation (focal stratification to form Sanderson cushions and papillae). Various steps in iodine/hormone metabolism can be blocked by chemicals, which thus can be used to treat thyroid functional aberrations.

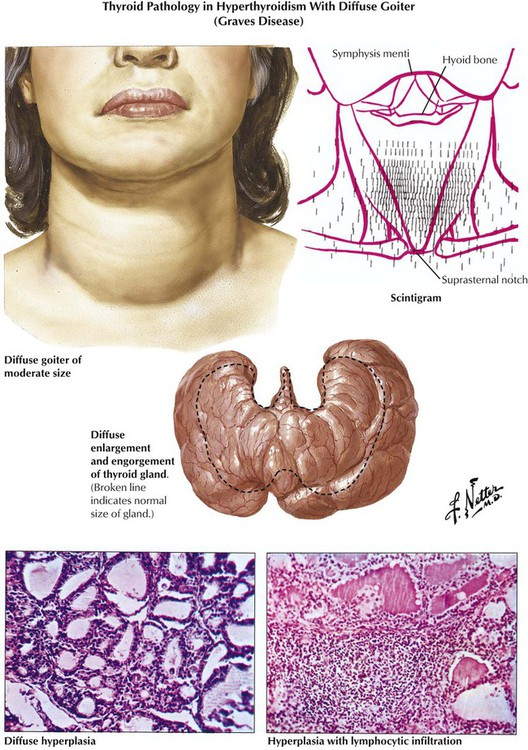

Hyperthyroidism is associated pathologically with diffuse or nodular goiter, Graves disease (morbus Basedow), thyroid adenoma and carcinomas, and certain forms of early thyroiditis. The etiology of Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, remains obscure. The diagnosis is confirmed by scintigraphic demonstration of increased T4, T3 uptake in the thyroid gland. Autoantibodies against follicular epithelial membranes, which may bind to the TSH receptor and thus contribute to thyroid stimulation, are frequently observed. The thyroid, which is grossly enlarged, firm, and red (struma parenchymatosa), shows histologically diffuse follicular activation and hyperplasia with resorption of colloid and eventual lymphocytic infiltration. The clinical course is variable, with exacerbations, remissions, and final hypothyroidism after secondary chronic nonspecific thyroiditis.

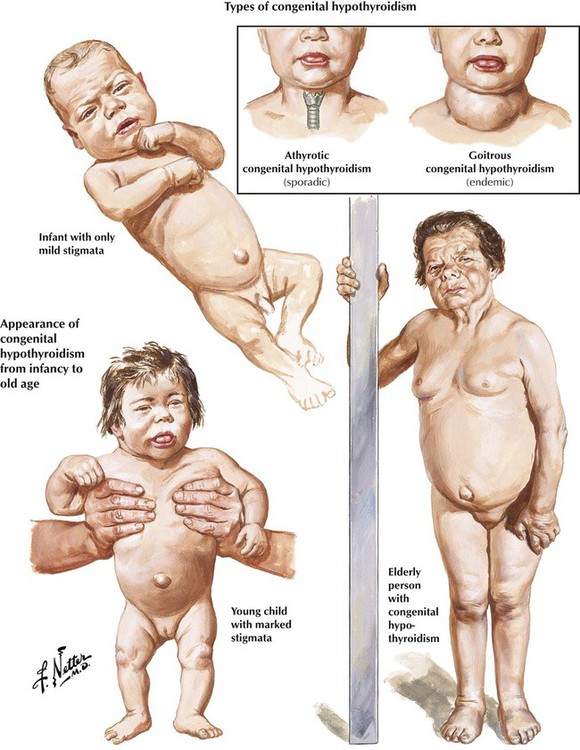

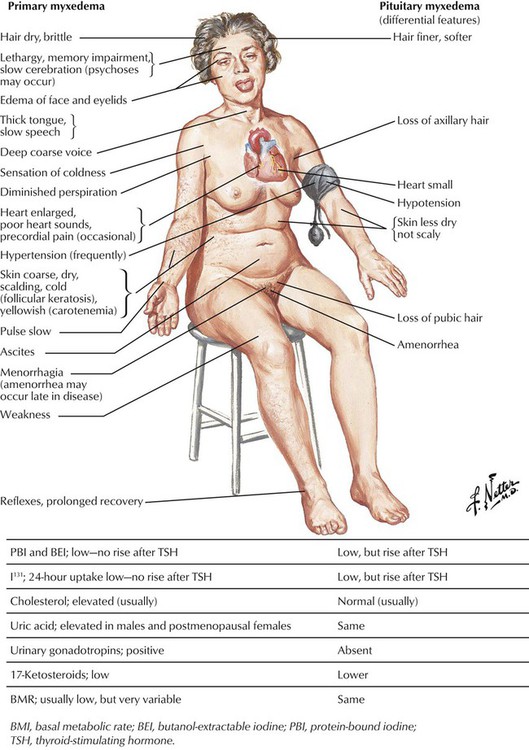

Hypothyroidism is characterized by a reduction of the physiologic thyroid function with respectively reduced thyroid hormone excretion. Congenital hypothyroidism is related to developmental defects and may occur endemically. In addition, there exists a sporadic, intrauterine post–inflammatory or post–toxic hypothyroidism with unresponsiveness of the thyroid gland to TSH stimuli and deficient thyroid hormone synthesis. Patients are of short stature, with thick yellowish skin and a characteristic facial expression. Eyelids are puffy, the nose is flat and thick, and the tongue is enlarged and protruding. The neck is short and thick. Adult hypothyroidism manifests as myxedema. Patients experience tiredness and lethargy. Their hair is dry and brittle, their skin is thickened (myxedema), and the face resembles to a certain extent that in cretinism. The heart rate is usually decreased, and some patients have psychotic crises (myxedema madness). Laboratory tests show a decrease of T4 levels in the blood, whereas TSH is significantly increased.

Goiter (struma) refers to an enlargement (usually nodular) of the thyroid related to either hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism. Goiter in combination with hyperthyroidism, as is seen in Plummer syndrome (toxic goiter), is usually autonomous but not cancerous. Goiter can be caused by low dietary intake of iodine but is usually caused by increased levels of TSH in response to a defect in hormone synthesis in the thyroid gland. Patients with goiter usually remain asymptomatic except for progressive swelling of the neck with potential airway obstruction and dysphagia or compression of the recurrent nerve with hoarseness. Microscopically, there is diffuse or nodular crowding of enlarged follicles. In time, regressive changes with chronic reactive inflammation and fibrosis develop. Focal intrafollicular hemorrhage and siderosis and follicle rupture with signs of colloid resorption and foreign body granulomatous reaction may occur.

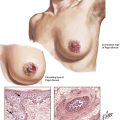

There are several forms of primary thyroiditis (Table 12-1). The thyroid gland is usually enlarged (except in Riedel thyroiditis, in which the gland is small to undetectable) and tender with radiating pain. Regional lymph nodes are enlarged, suggesting an inflammatory disease. Patients may be euthyroid with eventual hyperthyroidism related to follicle destruction (hashitoxicosis in Hashimoto disease) but eventually have hypothyroidism. Thyroid autoantibodies and cytotoxic T lymphocytes often can be shown. Some cases of autoimmune thyroiditis are part of systemic autoimmune disorders such as collagen-vascular diseases. Consequently, careful examination of the patient with primary thyroiditis is recommended. The nature of the autoimmune process usually determines the prognosis of the thyroiditis.

Autonomous proliferative diseases of the thyroid consist of adenomas (benign) and carcinomas (malignant), either of which may be hormone-producing tumors. Adenomas (usually autonomous nodules in a nodular goiter) show signs of hyperthyroidism, tachycardia, shortness of breath, nervousness, weight loss, and emotional instability, although they are usually less pronounced than in Graves disease. Iodine uptake is increased in the adenoma (scintigram), and blood iodine is moderately increased (protein-bound as well as butanol-extractable forms). Certain forms of adenoma are difficult to distinguish from well-differentiated follicular carcinoma (atypical adenoma with cellular atypia, mitoses, or even vascular invasion); therefore, adenomas should be removed and studied histologically (see also Table 12-3). The 4 major types of thyroid carcinomas (Table 12-2) differ histologically, in their routes of metastasis, and in their prognosis. Papillary, follicular, and anaplastic carcinomas are derived from follicular epithelial cells. Medullary carcinoma is an endocrine tumor from calcitonin-producing interstitial C cells. This tumor may occur in combination with other related endocrine tumors forming familial MEN syndromes, such as MEN-2 with associated pheochromocytoma. The clinical features of such tumors are determined by the combination of different neoplasms. Medullary carcinoma may show symptoms of carcinoids (flushing, watery diarrhea), Cushing syndrome, hyperparathyroidism (HPPT), and episodic hypertension. The life expectancy of patients with MEN is generally shorter than that of patients with solitary medullary carcinoma.

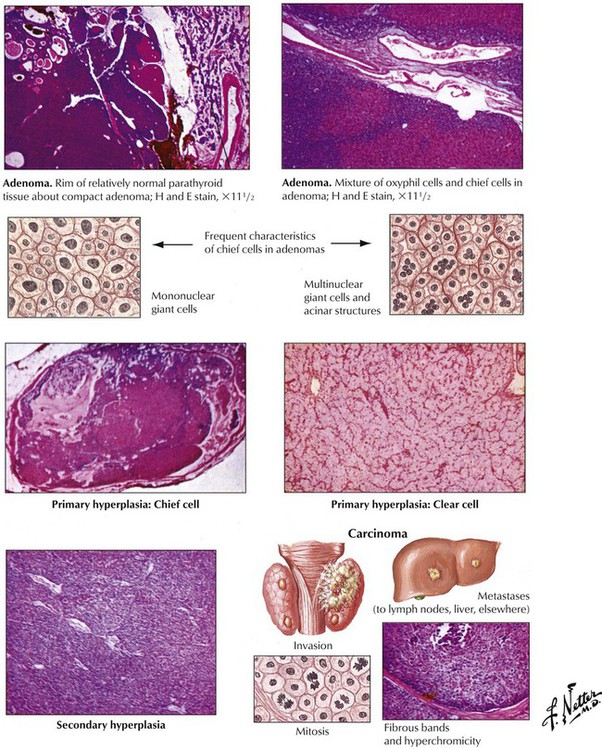

There are 2 major forms of hyperparathyroidism (HPPT), primary and secondary, as well as combinations of the two. Eighty-four percent of primary HPPT (autonomous HPPT) is caused by parathyroid adenomas, 12% is caused by hyperplasia, and 4% is caused by parathyroid carcinomas. Secondary HPPT follows chronic renal insufficiency (renal rickets, renal osteodystrophy) with hyperphosphatemia and decreased ionized serum calcium. Parathyroid glands show diffuse or nodular hyperplasia. Long-standing secondary HPPT may be complicated by development of autonomous adenomas, thus adding a form of primary HPPT. Clinical features of HPPT are variable combinations of serum hypercalcemia with calcium deposits (kidney stones, GI mucosa, blood vessels, soft tissues, etc.) and enhanced bone resorption (osteitis cystica fibrosa, dissecting fibroosteoclasia) (see also Table 12-3).

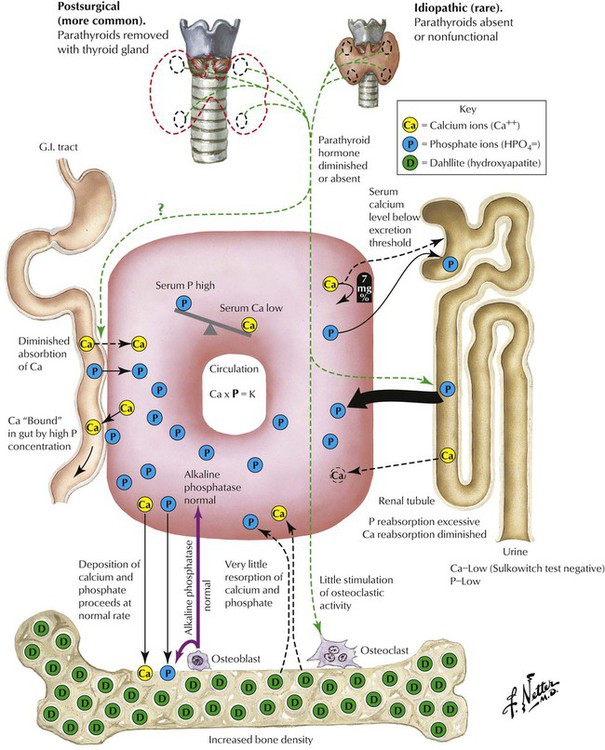

Hypoparathyroidism, the lack of PTH, is a rare condition that may follow surgical resection of parathyroid glands in thyroidectomy. It causes severe hypocalcemia with paresthesias, muscle spasms, and seizures. There are occasional familial autosomal recessive forms of hypothyroidism that occur as part of a multiglandular deficiency or in combination with T-cell immune deficiency (DiGeorge syndrome). The ionized serum calcium level provides the stimulus for PTH secretion. PTH stabilizes the serum calcium level by inhibiting renal tubular phosphate resorption and calcium/phosphate absorption in the bone. In addition, calcium absorption in the intestines may be enhanced. Calcitonin or thyrocalcitonin of thyroid interstitial C cells counteracts calcium absorption by decreasing the serum calcium level.

The adrenal cortex is composed of the zona glomerulosa (outer zone), the zona fasciculata (intermediate zone), and the zona reticularis (inner zone adjacent to adrenal medulla). The 2 inner zones respond to stimulation by hypophyseal corticotropin. The outer zone functions independently of corticotropin. This zone produces the hormone aldosterone in response to potassium and angiotensin (↑) or atrial natriuretic peptide and somatostatin (↓). The inner zones produce glucocorticoids and androgens in response to corticotropins. Increased functional activity may be caused by hyperplasia, adenoma or carcinoma, and decreased functional activity by atrophy (e.g., in malnutrition), necrosis (e.g., in septicemia, tuberculosis, viral infection), or autoimmune adrenalitis. Hyperplasia of glucocorticoid-producing parts results in Cushing disease as caused by excessive corticotropin stimulation. Corticotropin-independent forms of Cushing syndrome occur in autonomous cortical adenomas or carcinomas (see also Table 12-3).

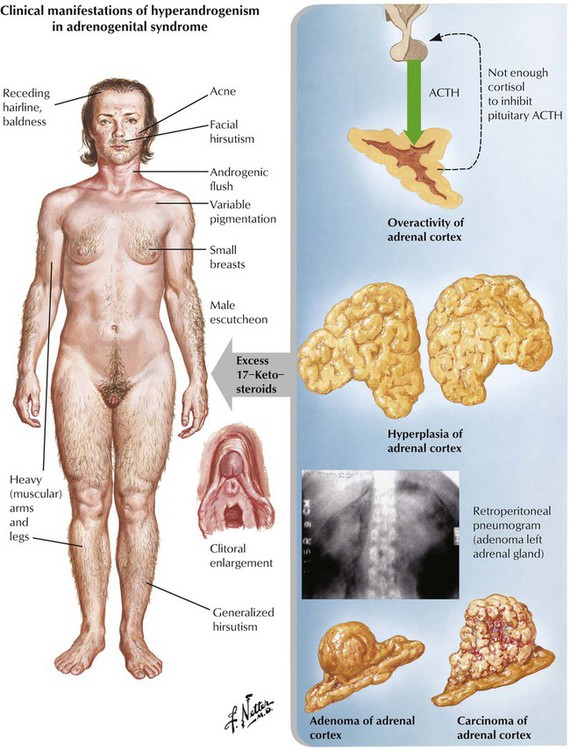

Adrenogenital syndrome (congenital and adult forms) is caused by a form of adrenal cortical hyperplasia or tumors with excessive production of 17-ketosteroids (dehydroepiandrosterone, etiocholanolone, and androsterone). In addition to androgen abnormalities, the syndrome may be complicated by alterations in sodium metabolism, glucocorticoid deficiency, or both. Clinically, there are signs of masculinization in females (hirsutism, clitoral hypertrophy, oligomenorrhea) and precocious puberty and enlargement of genitalia in males. Some forms of congenital adrenal cortical hyperplasia occur with androgen deficiency and cause pseudohermaphroditism in males. Ninety-five percent of patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia show defects in 21-hydroxylase, which results from mutations on chromosome 6.

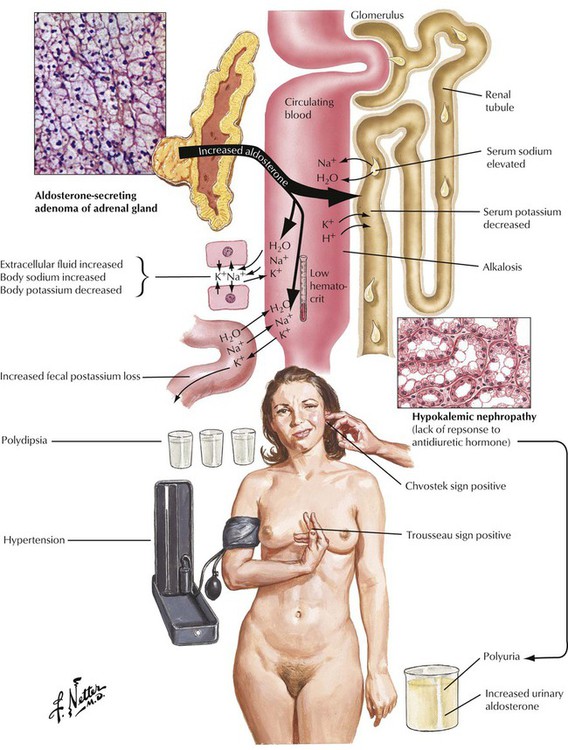

Adrenal cortical adenomas that simulate structures of the zona glomerulosa cause primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn syndrome). Excessive aldosterone secretion causes potassium depletion (increased potassium loss from kidneys and other exocrine glands), sodium retention, decreased plasma renin activity, and hypertension. Secondary hyperaldosteronisms in response to stimulation by the renin-angiotensin mechanisms show increased plasma renin activity. Adenomas in primary hyperaldosteronism usually remain small (less than 6 g) and can be difficult to identify clinically. Patients experience a metabolic alkalosis and muscle weakness.

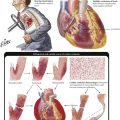

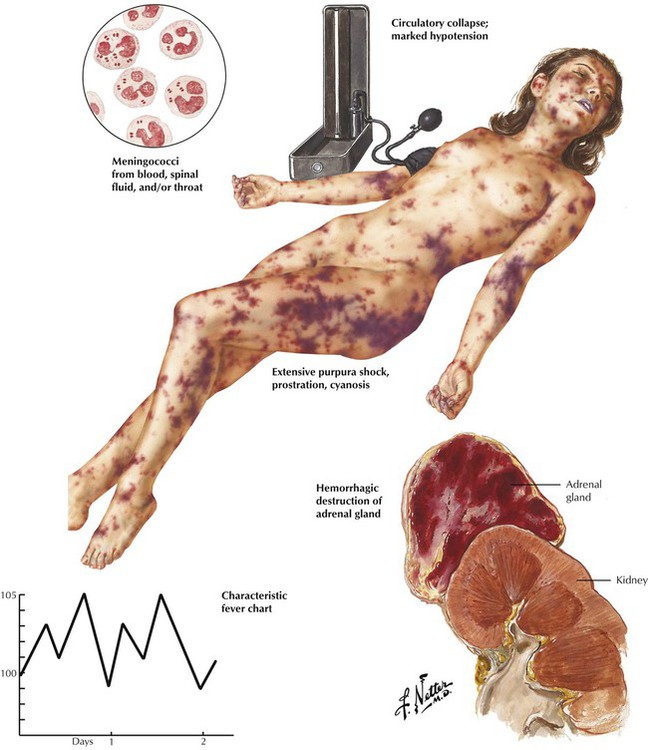

Acute adrenal cortical insufficiency (adrenal crisis, Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome) follows the acute necrosis and hemorrhage of the adrenal cortex secondary to bacterial septicemia, usually meningococcal septicemia, and sometimes Pseudomonas, pneumococci, and Haemophilus influenzae. Bacterial toxins (endotoxins) are thought to cause diffuse vascular damage with intravascular coagulation and hemorrhage, which destroy large parts of the adrenal cortex. Other conditions that may be associated with similar adrenal hemorrhage and necrosis are birth trauma, treatment with anticoagulants, and almost all causes of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The resulting acute adrenal crisis is attributed primarily to the sudden loss of glucocorticoids.

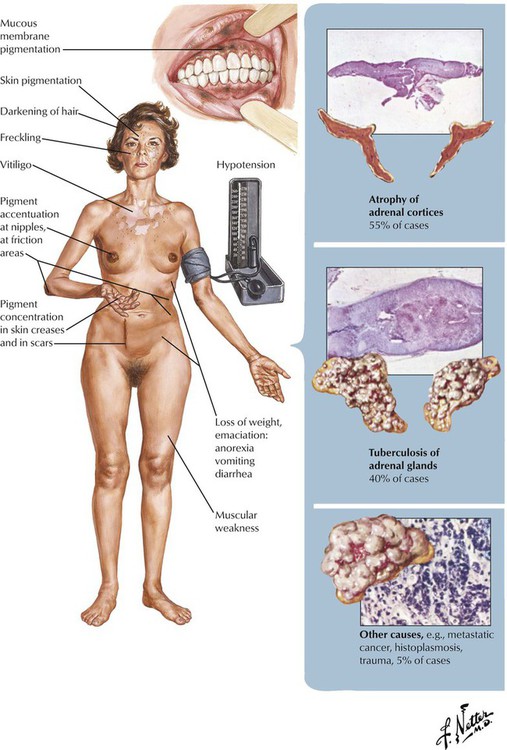

Chronic adrenal cortical insufficiency, Addison disease, is a clinical syndrome characterized by progressive weakness and fatigue, hypotension, weight loss, skin and mucosal hyperpigmentation, and abdominal problems. Laboratory test results show hyperkalemia, hyponatremia and volume depletion (decrease in mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone), and, occasionally, hypoglycemia (decrease in glucocorticoids). Patients without adequate replacement therapy die in coma. The underlying disease is a progressive shrinking (collapse) of the adrenal cortex secondary to epithelial atrophy and chronic inflammation (lymphocytic or granulomatous). In approximately two thirds of cases, autoimmune adrenalitis is responsible for these changes. Other cases are associated with infections (tuberculosis, fungal) or tumor metastases. Sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and hemochromatosis are less frequent causes.

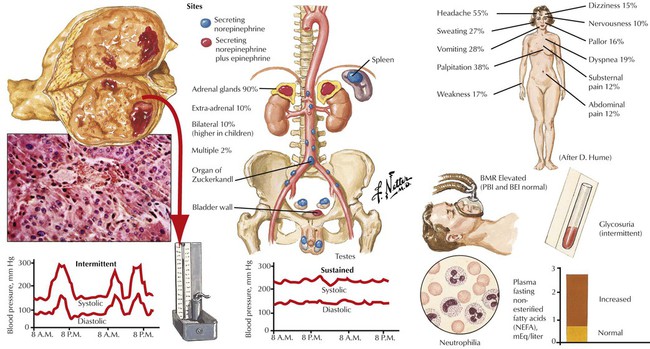

The adrenal medulla consists of typical chromaffin cells (affinity to chromium salts with dark staining on oxidation), which produce the catecholamines epinephrine (80% in the adrenal medulla) and norepinephrine. Tumors of chromaffin, catecholamine-producing cells, include pheochromocytoma and paragangliomas. Pheochromocytomas, smooth yellowish-tan nodules or large hemorrhagic masses of several kilograms, may be bilateral. Nests of amphophilic chromaffin cells with a finely granular, silver-stainable cytoplasm are seen microscopically. Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas are found in extraadrenal locations. Clinical features are headaches, intermittent hypertension, palpitation, and sweating. Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas are part of a familial syndrome called multiple endocrine neoplasia, autosomal dominant diseases with mutations on chromosomes 10 and 11, such as 11q13 (MEN type I) and 10q1.2 (MEN types II and III).

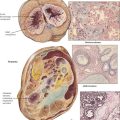

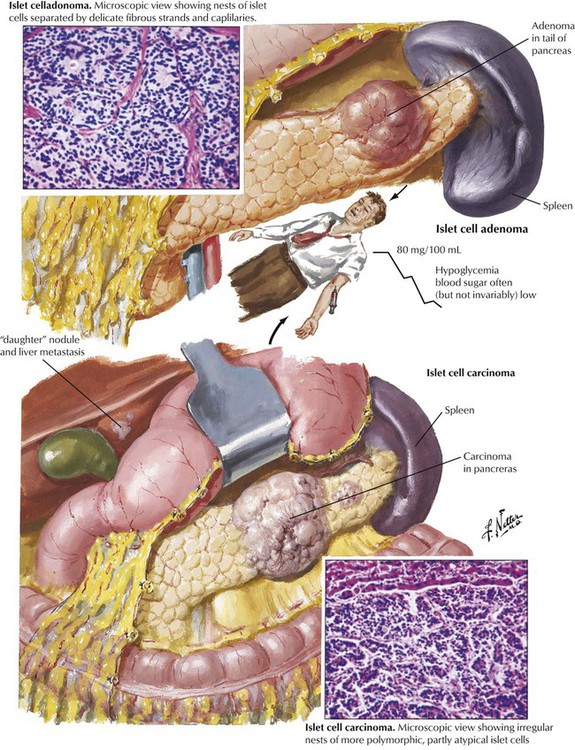

The endocrine pancreas consists of the islets of Langerhans, which are composed of insulin-producing β cells (60-70%), α cells (15-20%), which produce the “insulin-antagonist” glucagon, several clones of δ cells (e.g., D cells, D1 cells), which secrete somatostatin or vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and other substances. Hyperinsulinism caused by β-cell adenomas or carcinomas constitutes 75% of pancreatic endocrine neoplasms. Clinical features are spontaneous hypoglycemia with hunger, tremor, perspiration, confusion, anxiety, convulsions, and coma. In nesidioblastosis, which occurs in rare cases of reactive hypoglycemia, pancreatic β cells are hypertrophic and increased in number. Islet cell carcinomas (10% of insulin-producing tumors) are less well demarcated, metastasize early, preferentially to the liver, and generally are associated with a poor prognosis.

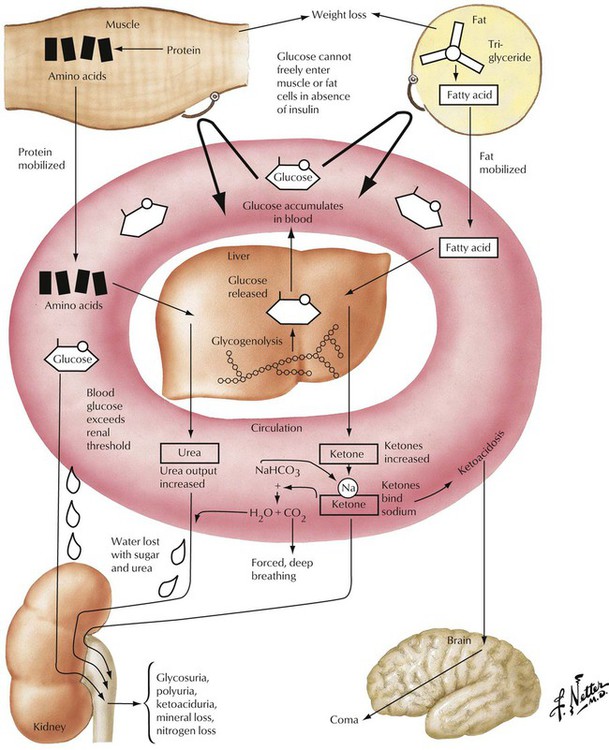

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM, type 1) is a complex disorder of carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism caused by hypoinsulinism and multiorgan disease. In IDDM, the progressive destruction of β cells in pancreatic islets usually begins before the age of 20 years. Microscopically, pancreatic islets show scattered lymphocytic infiltration (predominance of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes and anti–islet cell antibodies in up to 80%) with loss of β cells and mild fibrosis. Besides genetic predisposition, virus infections such as coxsackievirus are considered the initiating events for IDDM. The metabolic disturbance is characterized by hyperglycemia with mobilization of fat and protein, negative nitrogen balance, and acidosis. Polyuria leads to loss of electrolytes and dehydration, mobilization of fat and proteins, weight loss, and hunger.

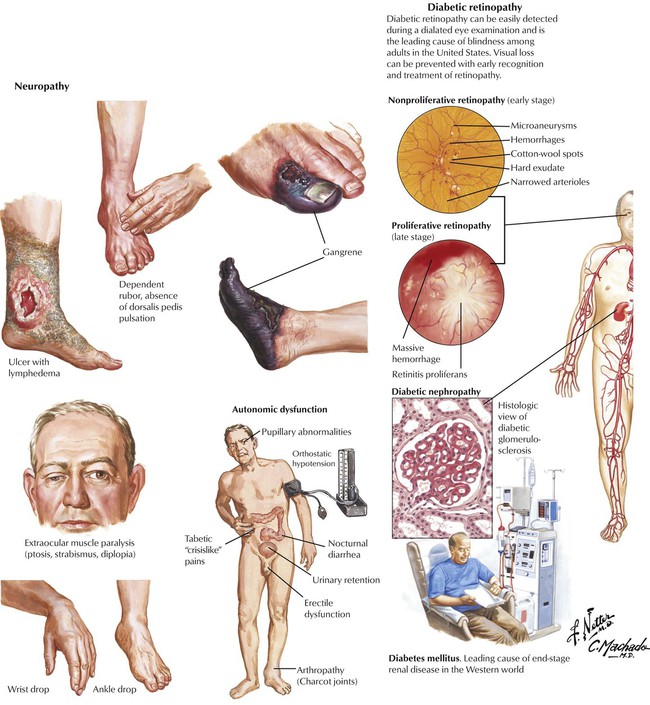

Non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM, type 2), the most common form of diabetes, is characterized by an initial decreased sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin (insulin resistance) followed by alterations in insulin secretion by β cells. Pancreatic islets show amyloid deposits, cell atrophy, and progressive fibrosis. The incidence of NIDDM increases with obesity and the consumption of glucose (in all nutritional forms). Metabolic disturbances, especially hyperglycemia, cause a number of complications and secondary diseases, including progressive microangiopathy with diabetic retinopathy, renal glomerular nephrosclerosis (Kimmelstiel-Wilson disease), peripheral neuropathy, ulcus cruris, and gangrene. Many patients have severe hypertensive cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of mortality in this population.