20 Endocrine surgery

Thyroid gland

Surgical anatomy and development

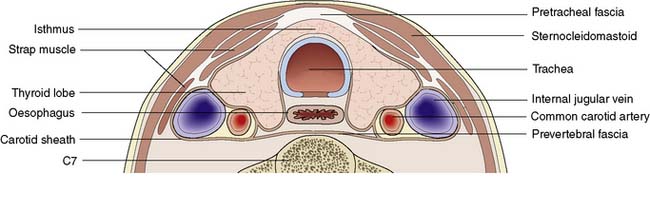

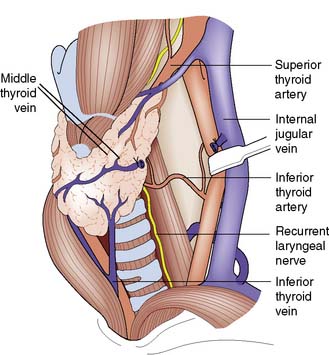

The lobes of the thyroid lie on the front and sides of the trachea and larynx at the level of the 5–7th cervical vertebrae (Fig. 20.1). They are connected by a narrow isthmus, which overlies the second and third tracheal rings. The thyroid normally weighs 15–30 g and is invested by the pre-tracheal fascia, which binds it to the larynx, cricoid cartilage and trachea (Fig. 20.2). The strap muscles (sternohyoid and sternothyroid) lie in front of the pretracheal fascia and must be separated to gain access to the gland. It is difficult to feel the normal thyroid gland except at puberty and during pregnancy, when physiological enlargement occurs.

Fig. 20.1 Anatomy of the thyroid gland.

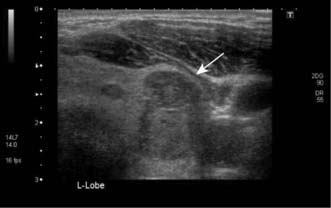

The middle thyroid vein has been divided to allow forward rotation of the left lobe of the gland.

Assessment of thyroid disease

The thyroid can be imaged by ultrasonography (Fig. 20.3) or radioisotope scanning (99mTc-sodium pertechnetate behaves like iodine and is ‘trapped’ by the gland). The main value of scanning is to differentiate between ‘hot’ (actively functioning), ‘cool’ (normally functioning) and ‘cold’ (non-functioning) thyroid nodules. Total isotope uptake also reflects thyroid activity.

Enlargement of the thyroid gland (goitre)

Clinical features

Goitre is a visible or palpable enlargement of the thyroid (Fig. 20.4). The swelling appears in the lower part of the neck and retains the shape of the normal gland (thyreos – Greek for shield). The swelling characteristically moves upwards on swallowing because of the gland’s attachment to the trachea. Patients may have a dry mouth, and when asking them to swallow, water should be provided.

Non-toxic nodular goitre

Investigations

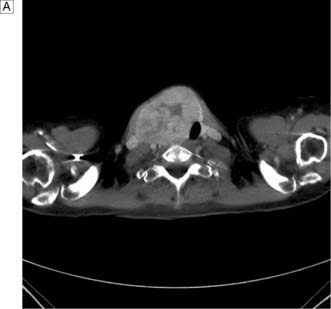

In the case of retrosternal goitre, plain films of the thoracic inlet may reveal tracheal deviation (Fig. 20.5A) and CT may show tracheal compression (Fig. 20.5B) The presence of stridor indicates compromise of the tracheal lumen. T3, T4 and TSH are usually normal and that being the case isotope scans are not indicated.

Thyrotoxic goitre

Summary Box 20.1 Goitres

• Physiological thyroid enlargement may occur during puberty or pregnancy

• Non-toxic nodular goitre can be associated with iodine deficiency and drug reactions; it is usually asymptomatic but can cause compression symptoms

• Thyrotoxic goitre results from stimulation of the gland by TSH or TSH-like proteins, resulting in excessive production of T3 and T4. About 25% of cases of thyrotoxicosis are due to a toxic multinodular goitre (a long-standing non-toxic goitre develops hyperactive nodule(s) that function independently of TSH levels)

• Thyroiditis can produce diffuse painful swelling that may be subacute (de Quervain’s disease) or autoimmune (Hashimoto’s disease). Riedel’s thyroiditis is a very rare cause of painless thyroid swelling and tracheal compression

• A solitary thyroid nodule is often a conspicuous palpable nodule in a multinodular goitre. True solitary nodules may be adenomas, cysts or cancers, conditions that are distinguished by fine-needle aspiration cytology, ultrasonography, isotope scans and function tests

• Thyroid cancers can produce a goitre, particularly in the case of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid and lymphoma.

Thyroiditis

Solitary thyroid nodules

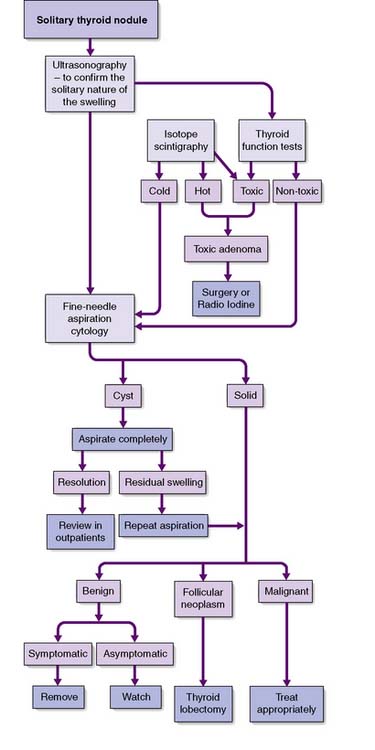

Slow-growing and painless clinically ‘solitary’ nodules are common, although 50% of them are really part of a multinodular goitre. Of the true solitary nodules, half are benign adenomas and the rest are cysts or differentiated cancers. The pivotal diagnostic test is fine-needle aspiration cytology, complemented by ultrasonography, isotope scans and thyroid function tests (Fig. 20.6). Cysts can be aspirated and, provided that they do not refill and that the cytology is negative for neoplastic cells, they need not be removed. Very rarely, a cyst contains a carcinoma (often papillary) within its wall, and blood-stained aspirate or a residual swelling after aspiration should raise this possibility. A cytopathologist cannot distinguish between a follicular adenoma and follicular carcinoma; this can only be achieved on definitive histopathology by looking for capsular or vascular invasion. Diagnostic surgery is needed if aspiration reveals a follicular neoplasm. Intraoperative frozen section does not always provide a definitive diagnosis, but the demonstration of carcinoma by whatever means indicates that more extensive surgery may be needed (e.g. complete total thyroidectomy).

Hyperthyroidism

Primary thyrotoxicosis (Graves’ disease)

Clinical features

Malignant tumours of the thyroid

Thyroid cancer accounts for less than 1% of all forms of malignancy. As with all thyroid disease, females are more often affected (male:female ratio 1:3). The two main types of thyroid carcinoma are papillary (50%) and follicular (30%), with the remainder comprising medullary carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma and lymphoma (EBM 20.1). The incidence of thyroid cancer is increased by exposure to ionizing radiation: for example, following the Chernobyl disaster.

20.1 Relevant websites and publications for the management of thyroid cancer are:

• www.aace.com/pub/guidelines/index.php American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, thyroid_carcinoma guidelines.

• www.baets.org.uk/Pages/guidelines/.php British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons.

• www.british-thyroid-association.org National thyroid cancer guidelines group of the British Thyroid Association.

• Northern Cancer Network. Guidelines for management of thyroid cancer. Clinical Oncology 2000; 12:373–391.

Follicular carcinoma

Clinical features

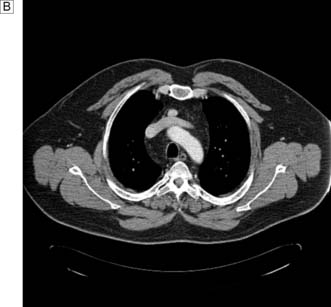

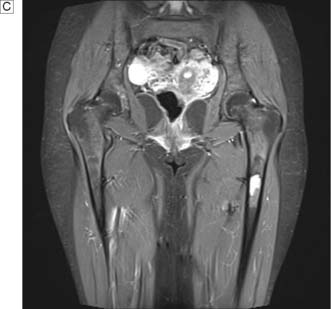

This disease typically presents as a solitary thyroid nodule in patients aged 30–50 years. Lymph node metastases are much less common than haematogenous spread, with deposits in the lungs, bone or liver (Fig. 20.8). Histologically, malignant cells are arranged in solid masses with rudimentary acini. Vascular and capsular invasion characterize this neoplasm and distinguish it from a benign follicular adenoma.

Thyroidectomy

Technique

Summary Box 20.2 Thyroid cancer

• Thyroid cancers may arise from the epithelium (papillary 50%, follicular 30%). Remainder comprise anaplastic, parafollicular C cells (medullary carcinoma) or lymphoreticular tissue (lymphoma)

• Papillary cancers are rare after the age of 40 years, are often multifocal and spread to lymph nodes, but rarely disseminate widely. Total or near-total thyroidectomy with the removal of involved nodes may be followed by radioiodine, and thyroid replacement therapy to suppress TSH. Ten-year survival rates approach 90%

• Follicular carcinoma occurs in the 30–50-year age group, spreads preferentially via the bloodstream, and is treated by total thyroidectomy. Residual neck or skeletal radioisotope uptake signals the need for radioiodine therapy. T4 is used routinely to suppress TSH production. The 10-year survival rate is 75%

• Anaplastic carcinoma occurs in older patients, spreads locally and frequently gives rise to pulmonary metastases. Curative resection is rarely possible, radiotherapy/chemotherapy is of little value, and most patients die within 1 year

• Medullary carcinomas secrete calcitonin, may involve both lobes, and involve neck nodes. They may be sporadic or part of MEN II. Treatment consists of total thyroidectomy and node dissection.

Parathyroid glands

Calcium metabolism

Hypercalcaemia and hypocalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia is a common biochemical abnormality and may be due to many causes other than excess PTH secretion (Table 20.1). Similarly, hypocalcaemia may be due to causes other than parathyroid removal or damage (Table 20.2).

| Hyperparathyroidism |

Table 20.2 Causes of hypocalcaemia

| Hypoparathyroidism |

| Hypoproteinaemia |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

Primary hyperparathyroidism

Management

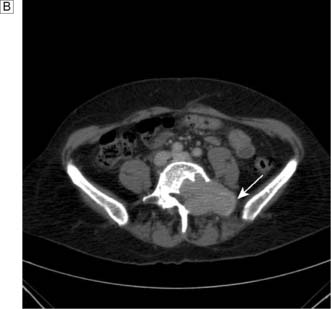

The aim of treatment is to identify and remove all over-active parathyroid tissue. Preoperative imaging with ultrasound and MIBI scans will allow selection of patients for a focused approach. Concordant scans permit a direct targeted incision over the suspected adenoma, with or without frozen section confirmation and intraoperative PTH monitoring. The latter two intraoperative tests are not employed by all surgeons and rarely make a difference to the outcome of surgery enough to justify their expense. With discordant imaging or associated multinodular goiter and previous neck surgery, traditional cervicotomy and four-gland exploration will be required. If two or more glands are enlarged, they should be removed. If all four glands are thought to be hyperplastic, then all but a portion of the smallest gland should be removed. If exploration fails to identify an adenoma or hyperplasia, the incision is closed. Reoperation is considered after (re)confirming the diagnosis and attempting to localize the gland using CT, MRI or selective venous catheterization (Fig. 20.9). Recurrent hyper-parathyroidism is approached in the same way but repeating first ultrasound and MIBI scans.

Secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism

Summary Box 20.3 Hyperparathyroidism

• Serum calcium levels are normally controlled by parathormone (mobilizes calcium from bone, and increases renal calcium absorption and phosphate excretion) and vitamin D (promotes absorption from the intestine and augments effect of parathyroid hormone (PTH) on osteoclasts), with an uncertain contribution from calcitonin

• Hyperparathyroidism may be primary (90% adenoma, 10% hyperplasia, 1% carcinoma), secondary to renal disease/malabsorption (low serum Ca2+ triggers PTH secretion) or tertiary (development of autonomous secretion in secondary hyperparathyroidism)

• Hyperparathyroidism is now normally diagnosed while asymptomatic, but can produce renal effects (nephrocalcinosis, calculi and failure), skeletal effects (demineralization), gastrointestinal upsets (peptic ulcer, pancreatitis) and psychotic symptoms, i.e. ‘stones, bones and groans’

• The diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism is supported by detection of circulating PTH in the presence of hypercalcaemia

• Primary hyperparathyroidism is treated surgically by removing an adenoma. If all four glands are involved by hyperplasia, all but a portion of one gland is removed.

Parathyroidectomy

Patient information

• the variable position of the glands

• the results of hyperfunction: renal effects, bone disease and systemic effects

• that only one gland is likely to be diseased and overactive, and that this is very rarely malignant (< 1%)

• that surgery will attempt to remove the abnormal gland but may fail to locate it because it is in an ectopic position

• that there may be a need for calcium and vitamin D supplements after surgery.

Pituitary gland

Surgical anatomy

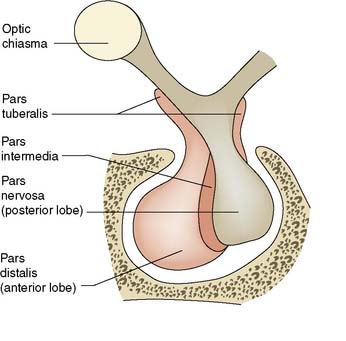

The pituitary gland is small and weighs about 500 mg. It is enclosed within a bony shell, the sella turcica, which is sealed superiorly by a fold of dura mater, the diaphragma sellae. The pituitary stalk connects the pituitary to the hypothalamus. The pituitary has two parts: the anterior pituitary (adenohypophysis) and the posterior pituitary (neurohypophysis) (Fig. 20.10).

Anterior pituitary

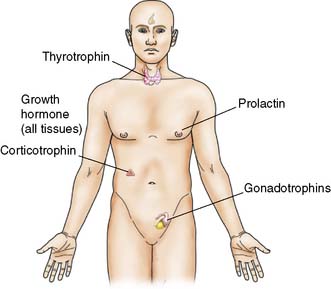

The anterior pituitary develops from an epithelial outgrowth from the pharynx (Rathke’s pouch). Some cells are thought to be of neural crest origin and belong to the APUD (amine and precursor uptake and decarboxylation) system. The anterior pituitary contains solid cords of secreting cells that used to be classified as acidophil, basophil or chromophobe on staining with haematoxylin and eosin. On the basis of immunofluorescence and other specific stains, these are now subdivided into cell types that secrete (Fig. 20.11):

• the polypeptides: growth hormone (GH), prolactin (PRL) and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH)

• the glycoproteins: luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and TSH.

Tumours of the anterior pituitary

Pathophysiology

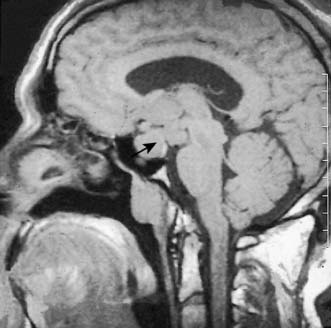

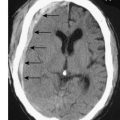

Functioning pituitary adenomas may result from over-stimulation by hypothalamic factors. Initially small and confined within the gland (microadenomas), they grow slowly and can ultimately expand the sella turcica. Eccentric enlargement is common. Upward extension of the adenoma may stretch the diaphragm or herniate through it, to compress the optic chiasma and cause visual defects. It is therefore important that pituitary adenomas are detected before they enlarge the fossa or extend above it. CT with contrast enhancement and MRI (Fig. 20.12) are used to image the tumour. Three endocrine syndromes caused by anterior pituitary disorders have surgical relevance.

Cushing’s disease

Summary Box 20.4 Tumours of the anterior pituitary gland

• May be detected while still small (microadenoma) or after it has expanded, often with upward extension to compress the optic chiasma

• The three endocrine syndromes that have surgical importance are acromegaly, hyperprolactinaemia and Cushing’s disease

• Acromegaly is due to excessive secretion of growth hormone (GH). Somatostatin analogues (or bromocriptine) can be used to normalize GH levels. Small adenomas are treated by removal; radiotherapy can be used for larger inoperable tumours

• Hyperprolactinaemia causes galactorrhoea and amenorrhoea in females, and impotence and gynaecomastia in men. Small adenomas are usually enucleated, whereas larger tumours are treated by bromocriptine

• Cushing’s disease may result from a functioning adenoma of ACTH-secreting cells, which is treated by removal or irradiation.

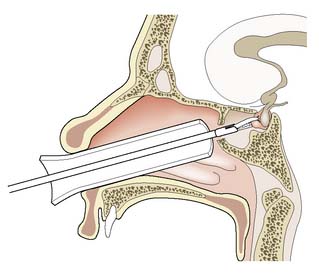

Surgical hypophysectomy

The transsphenoidal approach is preferred for the removal of a small adenoma. An operating microscope is used to approach the gland through the sphenoidal or ethmoidal sinuses (Fig. 20.13). Diabetes insipidus is rare. By placing a free flap of muscle in the fossa, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea is prevented. The transcranial approach is a major neurosurgical procedure that results in loss of the sense of smell and the development of diabetes insipidus. It is now reserved for the removal of large tumours with suprasellar extension, often in combination with a transsphenoidal approach.

The posterior pituitary

Pathophysiology

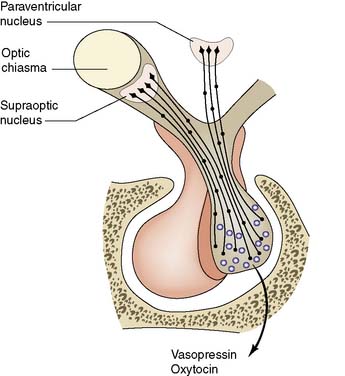

The neurohypophysis is part of a secretory and storage unit that includes the nerve cells of the supraoptic and paraventricular hypothalamic nuclei (Fig. 20.14). Fibres pass from these nuclei via the hypothalamo-hypophysial tract to the median eminence of the hypothalamus and posterior pituitary. The nerve cells secrete arginine vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone, ADH) and oxytocin, both of which pass down the nerve fibres to be stored in vesicles in the pituitary. The close anatomical relationship of the anterior and posterior pituitary has functional significance in that oxytocin release during lactation is paralleled by increased TSH and prolactin production, and the posterior pituitary may influence prolactin secretion by dopamine release.

Adrenal gland

Surgical anatomy and development

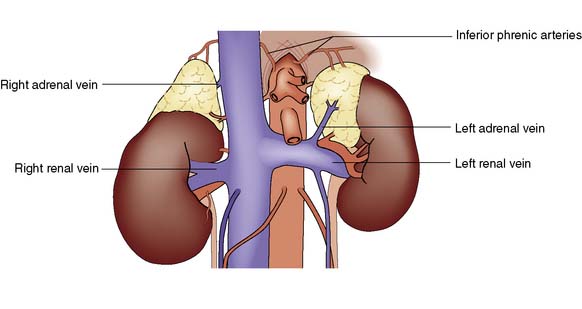

Each adrenal gland weighs approximately 4 g and lies immediately above and medial to the kidneys. The right adrenal lies in close contact with the inferior vena cava, into which it drains by a short wide vein that can be difficult to ligate at operation. The left adrenal vein drains into the left renal vein (Fig. 20.15). The glands are supplied by small vessels that arise from the aorta and the renal and inferior phrenic arteries.

Adrenal cortex

Cortical function

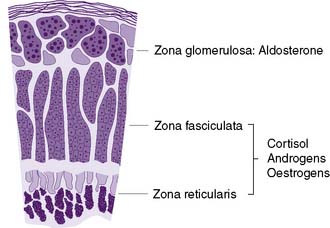

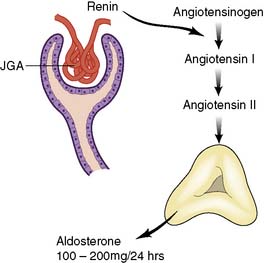

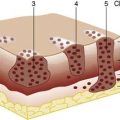

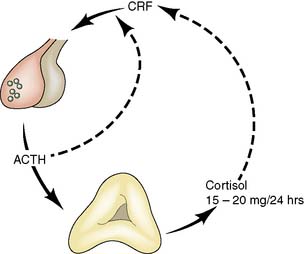

Microscopically, the adrenal cortex has three zones (Fig. 20.16). The outer zona glomerulosa secretes the mineralocorticoid, aldosterone. The zona fasciculata and zona reticularis act as a functional unit and secrete glucocorticoids (cortisol and corticosterone) (Fig. 20.17), androgenic steroids (androstenedione, 11-hydroxy-androstenedione and testosterone) and the inactive androgen and oestrogen precursor, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHA-S). Precursors of aldosterone (Fig. 20.18) are also synthesized by the fasciculata-reticularis zone, as are small amounts of progesterone and oestrogen. Only a fraction of the amount of hormone needed daily is stored in the cortex. The hormones are, therefore, secreted ‘to order’ and circulate either free (5%) or bound to α-globulin.

Fig. 20.17 Feedback loop in the control of cortisol secretion.

(ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic hormone; CRF = corticotrophin-releasing factor)

Summary Box 20.5 Adrenocortical hormones

• Cortisol secretion is controlled by pituitary adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). Cortisol protects against stress, maintains blood pressure and aids recovery from injury/shock. Its metabolic activities include protein breakdown, increased gluconeogenesis, reduced glucose utilization and mobilization/redistribution of fat and water

• In excess, cortisol has mineralocorticoid activity, can cause psychosis, and has anti-inflammatory effects (used in transplantation immunosuppression)

• Aldosterone secretion is controlled mainly by angiotensin levels (and thus by renin release from the juxtaglomerular apparatus during decreased renal perfusion)

• Aldosterone conserves sodium (by facilitating its exchange for potassium and hydrogen ions in the kidney) and is a major determinant of extracellular fluid conservation

• Androgenic steroids and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHA-S) are also secreted by the adrenal cortex. DHA-S is converted to testosterone and oestrogen in fat and liver, and this peripheral aromatization is the main source of oestrogen in postmenopausal women.

Cushing’s syndrome

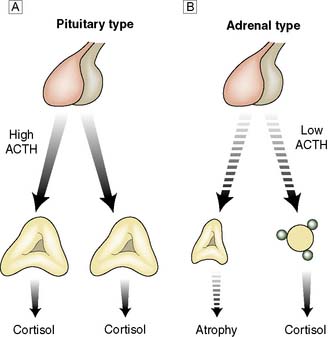

This syndrome was first described by the American neurosurgeon, Harvey Cushing. It results from any prolonged and inappropriate exposure to cortisol and has the following causes (Fig. 20.19):

• Tumours of the adrenal cortex (20%). Benign adenoma is the most common adrenal cause of Cushing’s syndrome. It is almost invariably unilateral and is more common in females. Histologically, the tumour contains clear cells like those of the zona fasciculata, or compact cells like those of the zona reticularis. Autonomous cortisol secretion inhibits ACTH production, so that the contralateral gland becomes atrophic and ceases to function. Adrenal carcinoma is a rare cause of Cushing’s syndrome that occurs more frequently in young adults and children. The tumour grows to a large size and has frequently metastasized by the time of presentation.

• Pituitary disease (80%). Pituitary tumours causing Cushing’s syndrome are usually basophil or sometimes chromophobe adenomas of ACTH-secreting cells. They range from tiny ‘microadenomas’ to large and even invasive tumours. Because of the continued ACTH secretion, both adrenals become hyperplastic. When Cushing’s syndrome is caused by a pituitary tumour, it is referred to as Cushing’s disease.

• Ectopic ACTH production. Inappropriate secretion of ACTH-like peptide by tumours of non-pituitary origin (e.g. pancreas, bronchus, thymus) is a rare cause.

• Iatrogenic. Cushing’s syndrome can be a major side effect of therapeutic steroid use. Adrenal atrophy occurs if the steroid dosage is supraphysiological (> 20 mg equivalent of prednisone per day) and prolonged in duration.

Clinical features

Cushing’s syndrome occurs most frequently in young women. The most striking feature is truncal obesity, a ‘buffalo hump’ (due to redistribution of water and fat) and ‘mooning’ of the face (Fig. 20.20). Cushing’s original description was a ‘tomato head, potato body and four matches as limbs’. As a result of protein loss, the skin becomes thin, with purple striae, dusky cyanosis and visible dermal vessels. Proximal muscle weakness is prominent. Other features include increased capillary fragility, purpura, osteoporosis, acne, loss of libido, hirsutism, diabetes, hypertension and amenorrhoea. The clinical signs develop insidiously over years and sometimes are only fully appreciated when the patients and their family review old photographs. In some cases, the disease runs a fulminant course, particularly when due to an adrenal carcinoma or ectopic ACTH secretion. Electrolyte disturbances, cachexia, pigmentation, severe diabetes and psychosis are common in these patients.

Investigations

Before proceeding to adrenalectomy, the surgeon must be convinced that:

• Cortisol secretion is beyond normal control. In Cushing’s syndrome plasma cortisol levels are high, diurnal variation is lost and secretion is not suppressed by low-dose dexamethasone

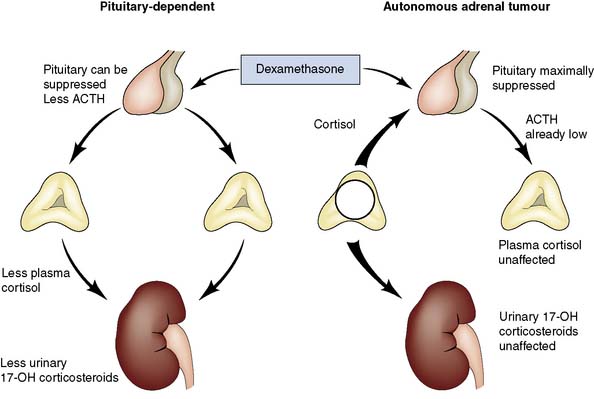

• The primary problem is in the adrenal. In patients with a functioning adrenal tumour, ACTH cannot be detected in the plasma, and urinary excretion of cortisol is not suppressed by high-dose dexamethasone (Fig. 20.21)

• Pituitary and ectopic sources of excessive ACTH production have been excluded. In Cushing’s disease due to a pituitary adenoma, plasma ACTH levels are inappropriately high and urinary cortisol excretion is suppressed by dexamethasone. In ectopic ACTH syndrome, the ACTH levels are often exceedingly high and there is an associated electrolyte disturbance. These patients may also have cancer cachexia

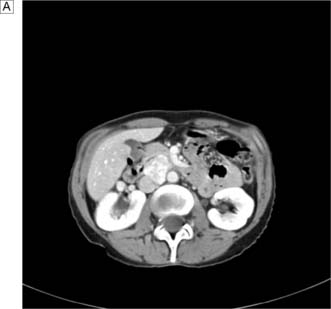

• Attempts have been made to localize the lesion by techniques such as CT (Fig. 20.22) or MRI.

Management

Pituitary disease

Summary Box 20.6 Cushing’s syndrome

• Cushing’s syndrome results from inappropriate secretion of cortisol

• May be caused by tumours of the adrenal cortex (20%), tumours of the anterior pituitary (80%), ectopic ACTH production (rare), or may be a side effect of steroid therapy

• The main clinical features are truncal obesity, buffalo hump, mooning of the face (‘tomato head, potato body, four matchsticks as limbs’), thinning of the skin, livid striae and proximal muscle weakness

• An adrenal tumour is usually treated by unilateral adrenalectomy, but cortisone replacement is needed until the suppressed contralateral adrenal recovers

• Before proceeding to adrenalectomy, the surgeon should confirm that cortisol secretion is beyond normal control, that the primary problem is not pituitary or ectopic ACTH production.CT scan is the optimal method of localization.

• Pituitary disease is best treated by pituitary surgery (or irradiation) rather than by bilateral adrenalectomy. This avoids continued growth of the pituitary tumour, problems due to ACTH and MSH production (pigmentation, Nelson’s syndrome), and the risks of adrenalectomy.

adrenalectomy removes all feedback control, so that over-production of ACTH and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) produces characteristic skin pigmentation, and continued growth of the adenoma may compress the optic chiasma (Nelson’s syndrome). Pituitary irradiation or surgery avoids the side-effects of adrenalectomy, and microsurgical removal of the adenoma is now the treatment of choice.

Hyperaldosteronism

Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome)

Diagnosis

• Confirm hypokalaemia. This may require repeated blood sampling without an occluding cuff; 24-hour urine collections usually show increased potassium excretion.

• Demonstrate hypersecretion of aldosterone. Plasma and/or urinary aldosterone levels are measured at 4-hourly intervals to allow for diurnal variations. Giving the aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone, should reduce blood pressure and reverse hypokalaemia.

• Exclude secondary hyperaldosteronism. Measurement of plasma renin is the critical investigation; renin levels are increased in secondary hyperaldosteronism but undetectable in the primary disease. Spironolactone causes further increases in renin levels in secondary hyperaldosteronism.

• Localize the adenoma. If primary hyperaldosteronism is confirmed biochemically, attempts should then be made to localize the adenoma by CT or MRI. Failure to ‘see’ an adenoma may mean that there is no discrete tumour and that the patient has bilateral cortical hyperplasia. Plasma cortisol levels should always be measured to exclude Cushing’s syndrome. Selective adrenal vein samplingto determine aldosterone levels is required to help localize small adenomas to one or other gland, and confirm which gland is hyperfunctioning.

Adrenal feminization

Summary Box 20.7 Management of pituitary disease

• Secreting macroadenomas are usually resected surgically

• Secreting microadenomas can be treated by specific drugs targeting the relevant hormone (e.g. bromocriptine for prolactin, somatostatin for growth hormone)

• Failed pituitary surgery for Cushing’s disease may require bilateral adrenalectomy to control hypercorticolism

• Following pituitary surgery careful monitoring of all pituitary hormones is required, as collateral damage can occur leading to occult deficiencies (e.g. TSH, ACTH, LH and FSH).

Adrenal medulla

Phaeochromocytoma

Investigations

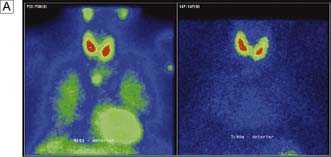

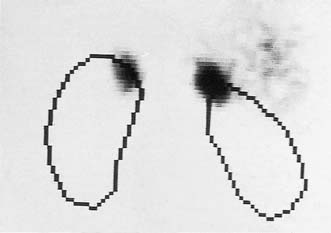

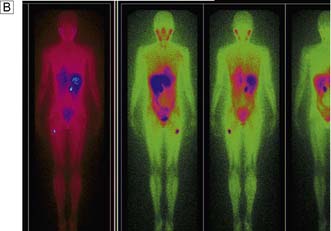

All young hypertensive patients (age < 40 years) should be screened for a catecholamine-secreting tumour. Twenty-four hour or overnight collections of urine should be analysed for metadrenaline and normetadrenaline levels. A CT or MRI may show the tumour. It may also be demonstrated by scintigraphy after giving radio-iodine-labelled metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), a catecholamine precursor taken up by sites of synthesis (Fig. 20.23).

Management

Summary Box 20.8 Phaeochromocytoma

• Usually benign tumour of the adrenal medulla (80%) but 20% arise in extra-adrenal paraganglionic tissue. 10% are multiple and 10% are malignant

• May be associated with neurofibromatosis, medullary carcinoma of the thyroid (MEN II), Von Hipple–Lindau disease, duodenal ulcer and renal artery stenosis

• Usually presents clinically with hypertension, which is often paroxysmal, and with metabolic effects such as diabetes mellitus

• All hypertensive patients < 40 years old should be screened for phaeochromocytoma; Overnight or 24 hour urinary and plasma metadrenaline and normetadrenaline levels are reliable methods of diagnosis

• Location is best defined by CT and radiolabelled metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scanning

• Treatment consists of adrenalectomy after careful preparation to control blood pressure and heart rate and to re-expand blood volume (by α-adrenergic blockade with β-blockade).

Adrenalectomy

Patient information

Summary Box 20.9 Management of adrenal pathologies

• Hyperfunctioning benign adrenal masses should be removed surgically (phaeochromocytoma, cortisol secreting adenomas and Conn’s syndrome). The laparoscopic approach is the preferred one

• Careful preoperative assessment to exclude multiple hormone secretions from a single or bilateral adrenal masses must be undertaken (e.g. a phaeochromocytoma that is also secreting cortisol)

• In primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome) preoperative selective venous sampling from both adrenals should be considered to confirm the site of maximal secretion. It can be misleading to assume this will be the side with the mass lesion in it

• Incidentally found adrenal masses must be investigated for possible hypersecretion of all adrenal hormones prior to their removal or a decision to leave them in situ and follow up.

• Have a low threshold to remove non-functioning incidentalomas > 3.5 cm in size, as the incidence of adrenocortical carcinomas increases significantly above this size

• Only biopsy an adrenal mass if you think it is due to a metastasis from a previous known malignancy. Always exclude a phaeochromocytoma before biopsy of any adrenal mass.

British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons’ Guidelines at www.BAETS.ORG.UK

for an adenoma producing Cushing’s syndrome, and after pituitary surgery) and the need for dosage increase at times of stress (e.g. other surgery) or intercurrent illness (e.g. pneumonia).