11 Endocrine surgery

Most surgical endocrine disorders are neoplastic, autoimmune or genetic. These conditions may or may not result in endocrine dysfunction depending on whether there is abnormal hormone secretion. The principles of endocrine surgery have been crystallised by John Lynn and are summarised in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Principles of endocrine surgery

| Principle | Example |

|---|---|

| Be convinced of the biochemical diagnosis | In Cushing’s syndrome, is the primary problem of pituitary or adrenal origin? |

| Make the patient safe | Control thyrotoxicosis in Graves’ disease, or hypertension in phaeochromocytoma |

| Localise the tumour(s) | In Conn’s syndrome, which side is the adenoma? CT and renal vein sampling may be necessary |

| Is an operation necessary? | Sometimes medical therapy is more effective, e.g. radioiodine for hyperthyroidism |

| Decide best technique | Open versus laparoscopic adrenalectomy |

The thyroid

Surgical anatomy

The thyroid is fixed to the trachea by the pretracheal fascia so it moves up on swallowing. Aberrant thyroid tissues may be found anywhere along the embryological descent of the gland. Blood supply is from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. Thyroid operations may damage important structures, highlighted in Table 11.2.

| Structure | Result of injury |

|---|---|

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve | Paresis or paralysis of vocal cord: unilateral – hoarseness bilateral – stridor; change in voice; risk of aspiration |

| Parathyroid glands | Hypocalcaemia – severity depends on amount of tissue that remains |

| External laryngeal nerve | Paresis or paralysis of cricothyroid muscle – inability to achieve high-pitched notes |

Goitre

Investigation

The aims of investigation are twofold:

• determine thyroid function (serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and T3/T4)

• exclude malignancy (by thyroid ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC)).

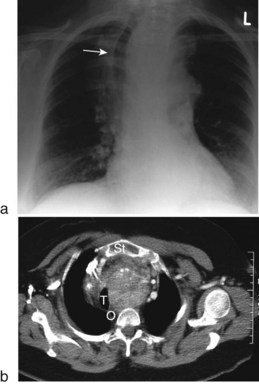

CXR ± CT may be useful to determine extent of larger goitres extending into the chest (Fig. 11.1).

Thyrotoxicosis

This is a common problem affecting 2% of females and 0.15% of males. The three main causes are:

Graves’ disease

This is the commonest cause of thyrotoxicosis, usually occurring between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Women are affected five times more often than males. Graves’ disease is due to an autoimmune process characterised by abnormal autoantibodies directed against thyroid TSH receptors. The natural history of Graves’ disease is one of intermittent remission and relapse. The thyroid is uniformly enlarged, firm and smooth, not nodular. Eye problems are common (Table 11.3). Thyroid function tests confirm an elevated T3 and T4 and reduced TSH. Anti-thyroglobulin and anti-microsomal antibodies are present when the cause is autoimmune.

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Poor sight for both near and distant objects | Ophthalmoplegia |

| Double vision | |

| Grittiness in the eye | Conjunctival oedema (chemosis) |

| Exophthalmos – protrusion of the globes | Exophthalmos |

| Lid retraction | |

| Lid lag |

Management of thyrotoxicosis

Treat eye complications (seek ophthalmology opinion); see Table 11.4.

Table 11.4 Management of eye complications in Graves’ disease

| Problem | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Exposed cornea with drying | Methylcellulose eye drops for lubrication |

| Failure of lid closure in marked exophthalmos | Tarsorrhaphy |

| Inflammation | Systemic steroids |

| Deterioration in sight from compressive optic atrophy | Surgical decompression of both orbits |

| Severe diplopia | Corrective surgery to eye muscles |

Clinical solitary thyroid nodule

The causes of a clinical solitary nodule are shown in Box 11.1.

Approximately 10% of solitary thyroid nodules are malignant.

Investigation

• Thyroid function tests exclude toxicity

• Ultrasound determines if the nodule is solitary or multiple (a dominant nodule in a multinodular goitre is the commonest cause of clinical solitary nodule). A cystic lump can be distinguished from a solid one

• Isotope scanning determines if the nodule is ‘hot’ or ‘cold’. Hot nodules are almost always benign; 15% of cold nodules are malignant

• Fine-needle aspiration cytology confirms the diagnosis in most cases.

Thyroid cancer

Thyroiditis

Thyroidectomy

Thyroidectomy is described on page 382. Complications of thyroidectomy are potentially life-threatening and are summarised in Table 11.5.

| Complication | Clinical features | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Bleeding into the neck | Acute airway obstruction with neck swelling, bruising and haematoma. The venous return from the head is also compressed, causing facial congestion and oedema | Give oxygen, sit upright, call surgeon and anaesthetist and immediately remove skin and strap muscle sutures to release the haematoma |

| Hypocalcaemia due to parathyroid gland injury | Typically 24–48 hours postoperatively. Paraesthesia round mouth and digits, then muscle spasm and tetany. Tapping the facial nerve below the ear causes facial spasm | Oral calcium usually adequate, IV calcium gluconate if necessary |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury | Unilateral palsy causes hoarseness of the voice. Bilateral partial RLN palsy causes severe airway obstruction | Usually conservative as most will recover |

| Speech therapy may help | ||

| External laryngeal nerve injury | Inability to sing, or project voice | Conservative |

| Thyroid crisis (thyrotoxic storm) caused by massive release of thyroxine into circulation during manipulation, e.g. gland in surgery | Severe thyrotoxicosis, restlessness, confusion, tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, hypotension, hyperpyrexia, cardiac arrest | Control of thyrotoxicosis preoperative is the best way of avoiding the problem. Treatment is urgent using propylthiouracil and beta-blockade, and potassium iodide |

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is the commonest cause of hypercalcaemia in the community (Box 11.2). Three subtypes are recognised.

1 Primary hyperparathyroidism whereby the parathyroid glands secrete inappropriately raised amounts of parathyroid hormone (PTH). Serum calcium is raised, negative feedback abolished and the level of PTH is inappropriately high for the level of calcium. The most common cause is adenomatous change in one parathyroid but there may be hyperplasia of all four or a carcinoma of one.

2 Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs in chronic renal failure, which causes a reduction in plasma concentration of calcium, thereby leading to hyperplasia of all four glands. If the cause of hypocalcaemia can be corrected, the parathyroids return to normal.

3 Tertiary hyperparathyroidism occurs if the stimulus in secondary hyperparathyroidism continues unchecked and parathyroid overactivity may become autonomous. It may occur following renal transplantation.

Adrenal disorders

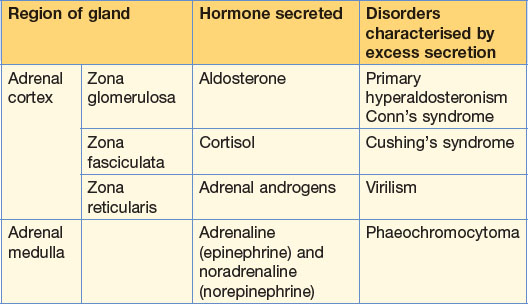

The adrenal glands, situated above the kidneys, are derived from two components, the cortex and medulla. The cortex has three zones, each secreting a different hormone (Table 11.6).

Table 11.6 Hormones synthesised by the adrenal glands, and the disorders characterised by excess secretion

Cushing’s syndrome

This affects patients between 20 and 40 years of age, and is more common in women. Causes of Cushing’s syndrome are shown in Box 11.3. Clinical features include trunk and facial obesity (moon face), buffalo hump, hirsutism, muscle weakness, osteoporosis and hypertension.

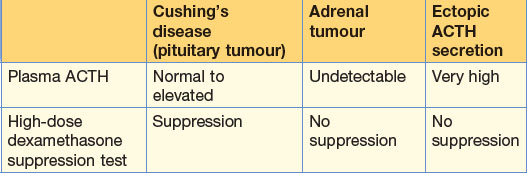

Diagnosis is confirmed by 24-hour urinary free cortisol, which is elevated. Plasma ACTH and high-dose dexamethasone suppression test identify the underlying cause of the abnormal cortisol secretion (Table 11.7).

Phaeochromocytoma

This is a catecholamine-secreting tumour of the adrenal medulla or in the paraganglionic tissues adjacent to the sympathetic chain (Box 11.4). Extra-adrenal tumours are more likely to be malignant and can be found anywhere from the pelvis to the base of the skull.

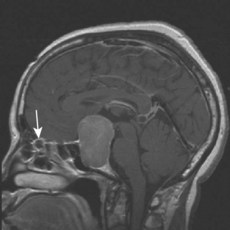

Pituitary

Pituitary tumours account for 10% of intracranial neoplasms. They are nearly always benign but cause problems due to local expansion (visual field defects due to pressure on the optic chiasma) and consequences of hypersecretion of one of the pituitary hormones (Fig. 11.2).

Figure 11.2 MRI scan, sagittal section, showing a large pituitary adenoma.

(Courtesy of Dr A. Mehta, with thanks.)

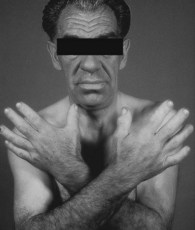

Acromegaly

Excess growth hormone secretion in adulthood results in acromegaly, the main appearance being overgrowth of the hands and feet and coarse facial features (Fig. 11.3). There are often physiological disturbances including glucose intolerance, osteoporosis and hypertension. Diagnosis is confirmed by elevated plasma growth hormone levels. Treatment is with drugs (octreotide), radiotherapy or surgery.