15 Endocrine disease

Pituitary disorders

Pituitary tumours

Treatment

Treatment (Table 15.1) options include surgery, radiotherapy and medical therapy, depending on the aetiology of the pituitary mass. Post-operative radiotherapy is used if significant tumour bulk remains after surgery or the underlying disease is still active. Radiotherapy results in a gradual decline of residual pituitary function over many years and must be monitored.

Table 15.1 Comparison of primary treatment for pituitary tumours

| Treatment method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical | ||

| Trans-sphenoidal adenomectomy or hypophysectomy | Relatively minor procedure Potentially curative for micro- and smaller macro-adenomas |

Some extrasellar extensions may not be accessible Risk of CSF leakage and meningitis |

| Trans-frontal | Good access to suprasellar region | Major procedure; danger of frontal lobe damage High chance of subsequent hypopituitarism |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| External (40–50 Gy) | Non-invasive Reduces recurrence rate after surgery |

Slow action, often over many years Not always effective Possible late risk of tumour induction |

| Stereotactic | Precise administration of dose to lesion | Long-term follow-up data limited |

| Yttrium implantation | High local dose | Only used in few centres |

| Medical | ||

| Dopamine agonist (e.g. bromocriptine) | Non-invasive; reversible | Usually not curative; significant side-effects in minority |

| Somatostatin analogue (octreotide) | Non-invasive; reversible | Usually not curative; expensive |

| Growth hormone receptor antagonist (pegvisomant) | Highly selective | Usually not curative; very expensive |

Hypopituitarism

Clinical features

Secondary hypothyroidism (p. 571) and adrenal failure (p. 582) both lead to tiredness and general malaise:

Examination

Investigation of pituitary function

• Basal serum investigations

• Dynamic tests

Management

Options for hormone replacement regimes are given in Table 15.2.

| Axis | Usual replacement therapies |

|---|---|

| Adrenal | Hydrocortisone 15–40 mg daily (starting dose 10 mg on rising/5 mg lunchtime/5 mg evening) (Normally no need for mineralocorticoid replacement) |

| Thyroid | Levothyroxine 100–150 mcg daily |

| Gonadal | |

| Male | Testosterone IM, orally, transdermally or implant |

| Female | Cyclical oestrogen/progestogen orally or as patch |

| Fertility | HCG plus FSH (purified or recombinant) or pulsatile GnRH to produce testicular development, spermatogenesis or ovulation |

| Growth | Recombinant human growth hormone used routinely to achieve normal growth in children Also advocated for replacement therapy in adults where growth hormone has effects on muscle mass and well-being |

| Thirst | Desmopressin 10–20 mcg 1–3 times daily by nasal spray or orally 100–200 mcg 3 times daily Carbamazepine, thiazides and chlorpropamide are very occasionally used in mild diabetes insipidus |

| Breast (prolactin inhibition) | Dopamine agonist (e.g. cabergoline 500 mcg weekly) |

FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; HCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin.

Thyroid disorders

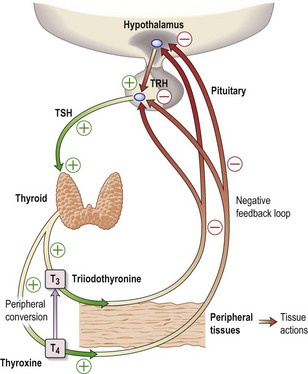

The thyroid hormones, T4 and T3, are produced within the thyroid gland. Synthesis and release are stimulated by TSH, which is released from the pituitary gland in response to the hypothalamic factor, TRH (thyrotrophin-releasing hormone) (Fig. 15.1). Predominantly, T4 is produced, but this is converted in the peripheral tissues (liver, kidney, muscle) to the more active T3. More than 99% of T4 and T3 circulate bound to plasma proteins, mainly thyroid-binding globulin (TBG).

Thyroid function tests

Problems in interpreting thyroid function tests

Hypothyroidism

Investigations

Treatment

Myxoedema coma

Hyperthyroidism

Clinical features

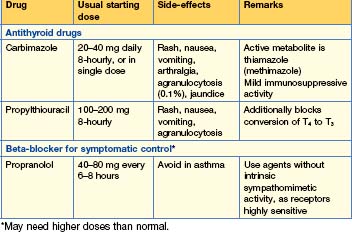

Treatment (Table 15.3)

There are three main options and preference varies widely.

Thyroid storm

Goitre

Investigations

Treatment

Reproduction and sexual disorders

Investigation of gonadal function

Female disorders

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS consists of oligomenorrhoea, hirsutism, acne and weight gain. Hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance and features of the metabolic syndrome (p. 429) are frequently seen. The syndrome probably arises from a combination of environmental and genetic interactions. Increased numbers of ovarian follicles may be found on US, but this is also seen in women without the syndrome.

• Investigations

Menopause

Menopause is diagnosed with loss of menses for 12 months, occurring at an average age of 50 years.

• Treatment

Hyperprolactinaemia

Acromegaly

Acromegaly is due to excess growth hormone release, usually from a benign pituitary adenoma.

Excess growth hormone results in a change of bodily appearance with coarsening of the features and an increase in shoe, glove and in particular ring size. Increased sweating is a common symptom, as is generalized lethargy and weakness — which may result from loss of ACTH but may also reflect loss of intrinsic muscle power despite increasing muscle bulk.

Investigation of growth hormone levels

Treatment

• Medical therapies

Cushing’s syndrome

Diagnosis

Treatment

Cushing’s disease (pituitary-dependent hyperadrenalism)

Adrenal insufficiency

Secondary adrenal failure

Assessment of the HPA axis

Management of adrenal failure (Table 15.4)

In primary adrenal failure, both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement is required.

| Drug | Dose |

|---|---|

| Glucocorticoid | |

| Hydrocortisone | 20–30 mg daily e.g. 10 mg on waking, 5 mg at 12:00 h, 5 mg at 18:00 h |

| or | |

| Prednisolone | 7.5 mg daily 5 mg on waking, 2.5 mg at 18:00 h |

| rarely | |

| Dexamethasone | 0.75 mg daily 0.5 mg on waking, 0.25 mg at 18:00 h |

| Mineralocorticoid | |

| Fludrocortisone | 50–300 mcg daily |

Emergency management of adrenal failure (Box 15.1) (also see Emergencies in Medicine p. 720)

Box 15.1 Management of acute hypoadrenalism

Long-term steroid therapy

Diabetes insipidus

Investigations

Treatment

Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH)

Treatment

Hypercalcaemia

Clinical features

Investigations and differential diagnosis

Treatment of hypercalcaemia (see Emergencies in Medicine p. 719)

Details of emergency treatment for severe hypercalcaemia are given in Box 15.3. Thereafter, treatment is management of the underlying disease.

Box 15.3 Treatment of acute severe hypercalcaemia

Treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Adrenal adenomas (Conn’s syndrome) and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia account for the majority of cases of primary hyperaldosteronism.