Endocrine control

Biochemical regulators

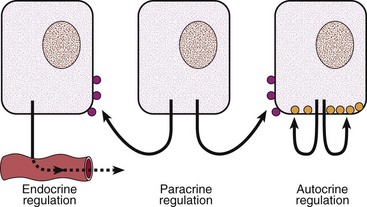

Homeostasis, the tendency to maintain stability, is essential to survival. It is achieved by a system of control mechanisms. Endocrine control is achieved by biochemical regulators. Some of these are hormones, i.e. they are released from specialized glands into the blood to influence the activity of cells and tissues at distant sites. Others are paracrine factors, which are not released into the circulation, but which act on adjacent cells, e.g. in the regulation of the immune system. Finally, autocrine factors act on the very cells responsible for their synthesis. These different kinds of regulation are illustrated in Figure 40.1.

Hormone structure

Three broad classes are recognized:

Peptides or proteins. Most hormones fall into this class, although they vary enormously in size. For example, the hypothalamic factor thyrotrophin-releasing hormone has just three amino acids, whilst the pituitary gonadotrophins are large glycoproteins with subunits.

Peptides or proteins. Most hormones fall into this class, although they vary enormously in size. For example, the hypothalamic factor thyrotrophin-releasing hormone has just three amino acids, whilst the pituitary gonadotrophins are large glycoproteins with subunits.

Amino acid derivatives. Examples include the thyroid hormones and adrenaline (epinephrine).

Amino acid derivatives. Examples include the thyroid hormones and adrenaline (epinephrine).

Steroid hormones. This large class of hormones includes glucocorticoids and sex steroid hormones, all of which are derived structurally from cholesterol.

Steroid hormones. This large class of hormones includes glucocorticoids and sex steroid hormones, all of which are derived structurally from cholesterol.

Assessment of endocrine control

Many endocrine diseases arise from failure of control mechanisms (Table 40.1). Assessment of endocrine control presents particular difficulties.

Table 40.1

Oversecretion

Cushing’s disease where a pituitary adenoma secretes ACTH

Undersecretion

Primary hypothyroidism where the thyroid gland is unable to make sufficient thyroid hormone despite continued stimulation by TSH

Failure of hormone responsiveness

Pseudohypoparathyroidism where patients become hypocalcaemic despite elevated plasma PTH concentration because target organs lack a functioning receptor signalling mechanism

Low concentrations. Hormone concentrations in blood are sometimes so low that they are at or below the lower limit of analytical detection. In the past, it was often the biological response to hormones that formed the basis of relatively crude bioassays of hormone activity. The advent of immunoassays in the 1960s revolutionized endocrinology by permitting the measurement of hormones that had previously been well below the limits of detection. However, despite the refinement of immunoassay technology by, for example, the introduction of monoclonal antibodies, measurement of structurally related hormones continues to be a problem for the clinical biochemistry laboratory, as is immunoassay interference (see below).

Low concentrations. Hormone concentrations in blood are sometimes so low that they are at or below the lower limit of analytical detection. In the past, it was often the biological response to hormones that formed the basis of relatively crude bioassays of hormone activity. The advent of immunoassays in the 1960s revolutionized endocrinology by permitting the measurement of hormones that had previously been well below the limits of detection. However, despite the refinement of immunoassay technology by, for example, the introduction of monoclonal antibodies, measurement of structurally related hormones continues to be a problem for the clinical biochemistry laboratory, as is immunoassay interference (see below).

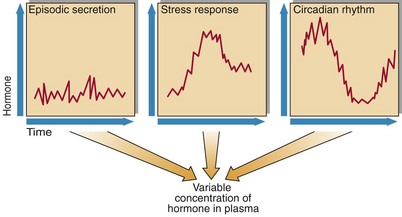

Variability. Even where it is possible to measure the concentration of a hormone accurately, the result of a single measurement may be difficult to interpret. This is because the concentration may vary substantially for various reasons, some of which are illustrated in Figure 40.2. For example, because growth hormone is released in a pulsatile fashion, an undetectable level is largely meaningless. The marked circadian rhythm of cortisol likewise makes interpretation of a random cortisol measurement on an untimed sample difficult or impossible.

Variability. Even where it is possible to measure the concentration of a hormone accurately, the result of a single measurement may be difficult to interpret. This is because the concentration may vary substantially for various reasons, some of which are illustrated in Figure 40.2. For example, because growth hormone is released in a pulsatile fashion, an undetectable level is largely meaningless. The marked circadian rhythm of cortisol likewise makes interpretation of a random cortisol measurement on an untimed sample difficult or impossible.

Hormone binding. Steroid and thyroid hormones bind to specific hormone-binding glycoproteins in plasma. It is the unbound or ‘free’ fraction of the hormone that is biologically active. Failure to measure the binding protein may lead to misinterpretation of hormone results. For example, accurate assessment of androgen status requires measurement of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in addition to testosterone; from both measurements the free androgen index is calculated.

Hormone binding. Steroid and thyroid hormones bind to specific hormone-binding glycoproteins in plasma. It is the unbound or ‘free’ fraction of the hormone that is biologically active. Failure to measure the binding protein may lead to misinterpretation of hormone results. For example, accurate assessment of androgen status requires measurement of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) in addition to testosterone; from both measurements the free androgen index is calculated.

Types of endocrine control

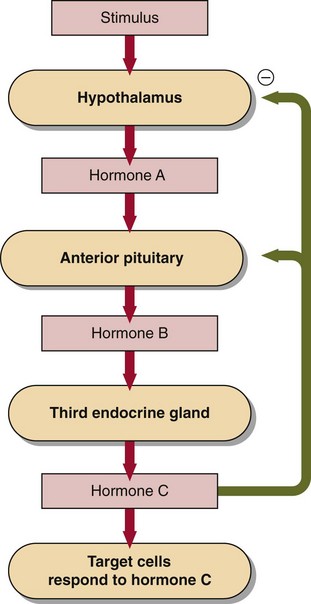

The basic operation of a negative feedback loop is shown in Figure 40.3. It is perhaps easier to understand the features of such a loop with reference to a particular axis, e.g. thyroid. Hormone A in this axis is thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH), hormone B is thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and hormone C is thyroid hormone (T4). Like a dial on a thermostat, the hypothalamus sets the point of optimal control for the system by secreting TRH at a certain level; this will correspond to a certain intended concentration of T4. By means of negative feedback from T4, the hypothalamus senses any difference between the actual concentration of T4 and the intended concentration, and readjusts the TRH level (set point) accordingly. This stimulates TSH release from the pituitary in a log-linear fashion, i.e. TSH rises exponentially with increasing TRH, thus permitting an extremely precise degree of control.

Positive feedback

Negative feedback control is ubiquitous in endocrinology, but there is one notable example of positive feedback. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, the release by the hypothalamus of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) fluctuates. Both follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) are released in response by the pituitary; the FSH stimulates the developing follicles to produce increasing amounts of oestrogen. At a particular point in the cycle the feedback from oestrogen on LH production switches from being negative to being positive, and the resulting LH surge triggers ovulation. The reasons for this switch are not entirely clear (after all, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis normally operates as a negative feedback loop), but positive feedback requires a threshold concentration of oestradiol (thought to be in the region of 700 pmol/L) to persist for at least 48 hours. The hormonal changes during a normal menstrual cycle are illustrated on page 101.

Pitfalls in interpretation

Immunoassay interference. Up to 40% of the population may have unsuspected antibodies that can interfere with immunoassays, by interacting either with the analyte being measured or with the antibody being used in the immunoassay mixture. These antibodies can produce falsely lowered or falsely raised results, with potentially serious consequences. Crucially, these interferences are specific to the patient’s serum, so quality control will not detect the problem. If there is a discrepancy between the clinical and biochemical pictures, or if a result is totally unexpected, this possibility should always be considered. This kind of problem is well recognized for some assays, e.g. thyroglobulin, prolactin.

Immunoassay interference. Up to 40% of the population may have unsuspected antibodies that can interfere with immunoassays, by interacting either with the analyte being measured or with the antibody being used in the immunoassay mixture. These antibodies can produce falsely lowered or falsely raised results, with potentially serious consequences. Crucially, these interferences are specific to the patient’s serum, so quality control will not detect the problem. If there is a discrepancy between the clinical and biochemical pictures, or if a result is totally unexpected, this possibility should always be considered. This kind of problem is well recognized for some assays, e.g. thyroglobulin, prolactin.

Log-linear responses. In response to alterations in TRH, TSH may rise exponentially. This kind of relationship means that the biological significance of a rise in TSH from 1 to 5 mU/L is the same as a rise from 10 to 50 mU/L. Moreover, this kind of relationship applies to all trophins released by the anterior pituitary, including growth hormone, the trophic hormone for insulin-like growth factors. Interestingly, the (skewed) distribution of serum prolactin behaves in a similar way, as if it too was a trophin like TSH or ACTH, even though, as yet, no prolactin-controlled hormone has been identified.

Log-linear responses. In response to alterations in TRH, TSH may rise exponentially. This kind of relationship means that the biological significance of a rise in TSH from 1 to 5 mU/L is the same as a rise from 10 to 50 mU/L. Moreover, this kind of relationship applies to all trophins released by the anterior pituitary, including growth hormone, the trophic hormone for insulin-like growth factors. Interestingly, the (skewed) distribution of serum prolactin behaves in a similar way, as if it too was a trophin like TSH or ACTH, even though, as yet, no prolactin-controlled hormone has been identified.

Dynamic function tests

Where the results of clinical assessment and baseline biochemical investigations fail to rule in or rule out a serious endocrine diagnosis, dynamic function tests may be required. Indeed, these are routine in the investigation of some disorders like acromegaly. They are dealt with in detail in pages 82–83.