Chapter 46 END-STAGE LIVER DISEASE

INTRODUCTION

End-stage liver disease is also known as decompensated liver disease. It develops in patients with underlying cirrhosis due to a wide variety of causes, including chronic hepatitis C, chronic hepatitis B, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty disease, autoimmune liver diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis) and genetic or metabolic liver diseases (alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, genetic haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease). Despite the wide aetiological processes involved in the development of cirrhosis, the manifestations of end-stage liver disease are common to all, and are consequent to the combination of portal hypertension and hepatic synthetic failure (Table 46.1). Extrahepatic manifestations of end-stage liver disease include hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. In addition, the presence of cirrhosis predisposes to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), bone disease and malnutrition.

| Complications of portal hypertension and portosystemic shunting |

ASSESSMENT

History

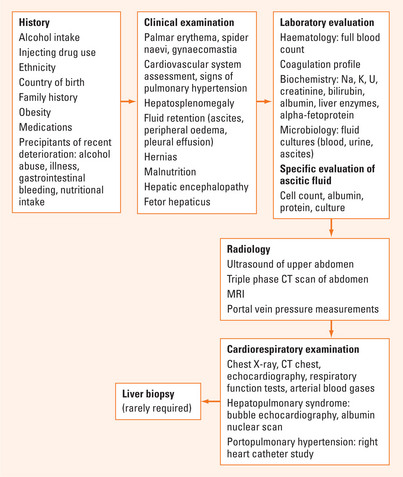

The essential elements of history taking for patients with end-stage liver disease (Figure 46.1) include:

Physical examination

Assessment of patient with end-stage liver disease (Figure 46.1) should include examination for:

Laboratory evaluation

In addition to the investigations listed, other specific investigations will be required to determine the cause of liver disease (Figure 46.1).

Evaluation of ascitic fluid

Radiologic investigations

Severity scores in end-stage liver disease

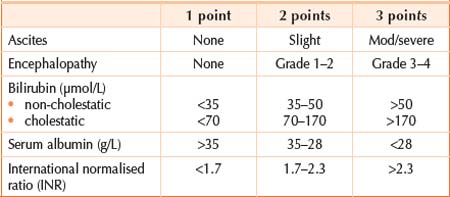

A number of scoring systems are used to assess severity of liver failure, and are used to determine prognosis, priority for liver transplantation and risks of procedures such as general anaesthesia or portosystemic shunt procedures. The two most commonly used systems are the Child-Pugh (Child-Turcotte-Pugh) classification (Table 46.2) and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD).

TABLE 46.2 Child-Pugh score for severity of liver disease. Child-Pugh A: 5–6; Child-Pugh B: 7–9; Child-Pugh C: 10–15

*To convert μmol/L to mg/dL, multiply by 0.01652. INR = international normalised ratio.

MANAGEMENT

Oedema, ascites and pleural effusions

Hyponatraemia

The management of hyponatraemia in patients with marked fluid retention can be extremely difficult. It should be remembered that despite often markedly low serum sodium levels, patients with oedema and ascites have increased levels of total body sodium. Thus attempts at correcting hyponatraemia by infusion of normal saline will result in further exacerbation of the oedema state, but usually with little change in serum sodium level. Appropriate management should include:

Hepatorenal syndrome

Diagnosis

Management

SUMMARY

The manifestations of end-stage liver disease are common to all aetiologies and result from a combination of portal hypertension and hepatic synthetic failure. Clinicians should be aware of clinical signs and laboratory findings in end-stage liver disease, and actively seek precipitants when sudden deterioration occurs. A patient’s status can change rapidly from being relatively stable, to being critically unwell. Management of bleeding gastro-oesophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial assessment and acute renal failure for example, require rapid assessment and introduction of life-saving interventions. Less acute, long-term management requires careful attention to diet to ensure appropriate salt and fluid restrictions, and adequate protein and caloric intakes, as well as monitoring for complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma.

Cordoba J, Lopez-Hellin J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41:38-43.

Garcia-Tsao G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:726-748.

Gines P, Cardenas A, Arroyo V, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:1646-1654.

Gines P, Torre A, Terra C, et al. Review article: pharmacological treatment of hepatorenal syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 3):57-62. discussion: 63–4

Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258-266.

Sharara AI, Rockey DC. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:669-681.

Wong F, Bernardi M, Balk R, et al. Sepsis in cirrhosis: report on the 7th meeting of the international ascites club. Gut. 2005;54:718-725.