Chapter 35 Employment Of Persons With Disabilities

Disability is a significant public health and social issue in the United States. The number of Americans who experience disability, activity limitations secondary to chronic illnesses, or impairments has increased, whereas mortality has decreased. A U.S. Census Bureau report found in 2005 that of a total population of 291.1 million, approximately 54.4 million (18.7%) individuals reported some degree of mental or physical disability.40 This represents an increase from the 51.2 million who reported a disability in 2002.40 In the 2005 report, 35 million people—or 12% of U.S. residents—were classified as severely disabled.40 Given these findings, disability ranks as the nation’s largest public health problem.∗

The growing numbers of Americans with disabilities present new medical, social, and political challenges. The major activity limitations found in those with disabilities include an inability to manage personal care, the inability to work and be financially self-supporting, and the inability to integrate socially and enjoy leisure.38 These limitations have medical, behavioral, social, and economic implications. To help those with disabilities restore functional capacity, prevent further deterioration in functioning, and maintain or improve their quality of life, programs of any type should emphasize rehabilitation and prevention of secondary conditions.30 These programs must respect disability as multifaceted and foster an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

Within the medical arena, the specialty of physical medicine and rehabilitation has been concerned with the establishment of physiologic, psychologic, and social equilibrium for persons with disabilities.19 According to Rusk, “A rehabilitation program is designed to take a disabled person from his bed back to his job, fitting him for the best life possible commensurate with his disability and more importantly with his ability.”33 To help all persons with disabilities achieve their maximum level of independence, avert further deterioration in functioning, and maintain or improve their quality of life, the physiatrist and the medical rehabilitation team must appreciate the multifaceted character of disability. We must accept the responsibility to initiate appropriate referrals to other collaborating programs that can support these goals beyond the medical arena. One such program is vocational rehabilitation.

In this chapter, we examine the subject of employment of people with disabilities. Specifically, we:

The Concept of Disability

Disability itself is not always quantifiable. In the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 an individual with a disability is defined as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.40 The concept of disability differs among persons who consider themselves to have a disability, professionals who study disability, and the general public.22 This lack of agreement is an obstacle to all studies of disability, as well as to the equitable and effective administration of programs and policies intended for people with disabilities.12,13,22,28,30

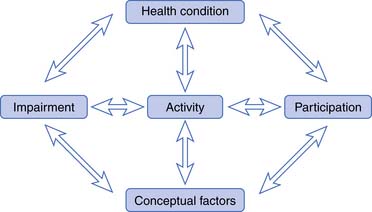

This biopsychosocial model regards functioning and disablement as outcomes of interactions between health conditions (disorders or diseases) and conceptual factors such as social and physical environmental factors and personal factors. The interactions in this paradigm are dynamic, complex, and bidirectional (Figure 35-1).

Dimensions of dysfunctioning are defined as follows.

The concept of disability or disablement continues to be one about which there are many interpretations and opinions. This lack of agreement about the concept of disablement affects epidemiologic studies of disablement and the development of effective treatment and prevention strategies. The biopsychosocial model and the common language of the ICIDH-2 helped to define the need for health care and related services; define health outcomes in terms of body, person, and social functioning; provide a common framework for research, clinical work, and social policy; ensure the cost-effective provision and management of health care and related services; and characterize physical, mental, social, economic, and environmental interventions that would improve lives and levels of functioning.51

The 2001 World Health Assembly subsequently endorsed a revised system, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). This is a classification of health and health-related domains, which are classified from body, individual, and societal perspectives using a list of body functions and structure, as well as a list of domains of activity and participation. The ICF also includes a list of environmental factors to provide context for the disability.53 The ICF provides a common transcultural language across health care systems and is intended to allow comparison of international data and the measurement of health outcomes, quality, and cost, as well as health disparities.

Data: Impairment and Disability

The U.S. Census Bureau provides extensive information on the number and characteristics of people with disabilities. Data from the Americans with Disabilities Report of 2005 indicate that 54.4 million people, or 18.7% of the U.S. population,40 have some level of disability. Among those 15 years or older, inability to walk without an assistive device was reported by 10.2 million individuals, and 3.3 million individuals required a wheelchair. Requiring help with one or more activities of daily living was reported by 4.1 million.40

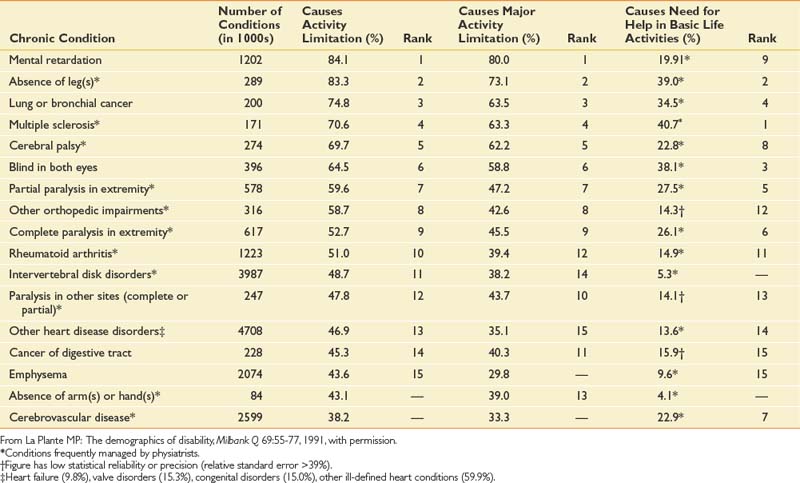

Impairments resulting from chronic disease have become increasingly significant risk factors of disability.8,22 Table 35-1 lists the 15 conditions with the highest prevalence of functional compromise or disability.22 The prevalence of disability with these conditions appears to be due to the prevalence of the condition itself and the chance that the condition will cause a disability. Table 35-2 shows the ranking of persons, by percentage of specific conditions, who have functional limitations secondary to that condition.22 In general, many of the conditions that are significant risk factors for disability are low in prevalence. For example, multiple sclerosis has a low overall prevalence but is a significant risk factor for disability. Examination of this ranking shows 7 of the top 10 disabling conditions are conditions frequently managed by the physiatrist and the rehabilitation team. These conditions or diseases are typically chronic, requiring a lifetime of rehabilitative management to have an effect on the disabling process, prevent secondary conditions, and maintain quality of life.

Table 35-1 Conditions With the Highest Prevalence of Activity Limitation

| Main Cause | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Orthopedic impairments | 16.0 |

| Arthritis | 12.3 |

| Heart disease | 22.5 |

| Visual impairments | 4.4 |

| Intervertebral disk disorders | 4.4 |

| Asthma | 4.3 |

| Nervous disorders | 4.0 |

| Mental disorders | 3.9 |

| Hypertension | 3.8 |

| Mental retardation | 2.9 |

| Diabetes | 2.7 |

| Hearing impairments | 2.5 |

| Emphysema | 2.0 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.9 |

| Osteomyelitis or bone disorders | 1.1 |

| All Causes | |

| Orthopedic impairments | 21.5 |

| Arthritis | 18.8 |

| Heart disease | 17.1 |

| Hypertension | 10.8 |

| Visual impairments | 8.9 |

| Diabetes | 6.5 |

| Mental disorders | 5.6 |

| Asthma | 5.5 |

| Intervertebral disk disorders | 5.2 |

| Nervous disorders | 4.9 |

| Hearing impairments | 4.3 |

| Mental retardation | 3.2 |

| Emphysema | 3.1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.9 |

| Abdominal hernia | 1.8 |

From La Plante MP: The demographics of disability, Milbank Q 69:55-77, 1991, with permission.

Socioeconomic Effect of Disability

Disablement has significant socioeconomic consequences for the individual with disabilities and for society. When a person is unable to participate in her or his social role as a worker or homemaker because of a physical or mental condition, that person is said to have a work disability or a work participation restriction.7,54 Work participation restriction results in dependency and loss of productivity for that person. Society, in turn, incurs direct and indirect costs.

Direct expenditures include those for medical and personal care, architectural modification, assistive technology, and institutional care, as well as income support for the person with a disability. For the individual, these expenses contribute to impoverishment.6,49 Society’s response to the expenditures related to disablement includes disability-related programs such as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Medicare, and Medicaid. In 2002, federal and federal–state programs for working-aged people with disabilities were estimated to cost $276 billion, or 2.7% of the gross domestic product (GDP) of the United States.11

Disablement is costly to the individual and to society because of the loss of productivity. People with disabilities are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed and have lower average salaries than their nondisabled peers (Table 35-3). The indirect monetary costs for the individual are reckoned in terms of losses in earnings and homemaker services.55 A 2006 study by researchers at the University of California, using 1997 as an example year, found that people with disabilities were estimated to spend an average of 4.5 times as much on medical expenses55 and that the overall net salary loss associated with disability was $115.3 billion, or 1.4% of the 1997 GDP.55

Disablement is associated with poverty. In 2007, 21% of disabled people 5 years and older were below the poverty level as opposed to only 10.9% of those without a disability.41 In 2005, people 21 to 64 years of age without a disability had median monthly earnings of $2539. Those with a nonsevere disability had $2250 median monthly earnings, and those with a severe disability had $1458 median monthly earnings (Table 35-3).40 The indirect monetary cost to society is loss from the labor force.6 For example, in 1996, spinal cord injury alone was estimated to have cost the U.S. economy $9.73 billion, including $2.6 billion in lost productivity.24

Disablement imposes indirect nonmonetary costs to the individual and to society. Fifty-seven percent of persons with disabilities believed their disability prevented them from reaching their full potential.14 Restriction in work participation, in particular, places the individual in a position of dependency on insurance payments or government benefits for income support and medical care. Dependency affects people’s feelings about themselves and their overall satisfaction with life.

Vocational rehabilitation is an intervention that can limit restrictions in work participation. In 1993, the Social Security Administration estimated that for every dollar spent on vocational rehabilitation services, five dollars in future direct expenditures was saved.23 A 2006 analysis of spending by the New Mexico Division of Vocational Rehabilitation found a total benefit/cost ratio of 5.63.29 Although employment is the expected outcome of vocational rehabilitation, the impact of this intervention goes beyond simple employment and saving of direct expenditures. The positive effects of working are demonstrated when the characteristics of working and nonworking persons with disabilities are compared. Those who work are better educated, have more money, are less likely to consider themselves disabled, and in general are more satisfied with life.14

Comprehensive rehabilitation of persons with disabilities should include strategies that reduce work restrictions, such as vocational rehabilitation. The outcomes include increased independence and increased productivity. The cost-effectiveness of comprehensive rehabilitation should be measured in direct and indirect monetary and nonmonetary costs over the lifetime of the individual.3

Disability-Related Programs and Policies

Programs

A plethora of disability-related programs and policies exist. Each program and policy has its own definition of disablement and disability, and differs in the eligibility and application criteria. The programs can be characterized as ameliorative or corrective.16 Ameliorative programs provide payment for income support and medical care. Corrective programs facilitate the individual’s ability to return to work and to reduce or remove the disablement. Whether ameliorative or corrective, all programs influence the biopsychosocial model of disablement.

Disability-related programs can be categorized into three basic types: cash transfers, medical care programs, and direct service programs. Table 35-4 presents specific programs within these three basic types.7 Estimates of the expenditures of these disability-related programs provide insight into expenditure trends. In 1970, 61.4% of the disability dollar went for cash transfers, 33% for medical care, and 5.4% for direct services. By 1986, the proportion of the disability dollar for direct services had decreased to 2.1%, while the proportion for medical care had increased.7 In 2002, of the estimated $276 billion spent, 41.9% went to income maintenance, 54.2% went to health care programs, 2% went to housing and food, and 1.5% for education training and employment.11 The trend toward ameliorative programs’ capturing more of the resources is a concern. Studies of the socioeconomic consequences of disability support the utility of rehabilitating people with disabilities, allowing them to enter the labor market and thereby decrease their dependency and loss of productivity.

| Type of Program | Specific Programs |

|---|---|

| Cash transfer | Social insurance: Social Security Disability Insurance |

| Private insurance | |

| Indemnity compensation | |

| Income support: Supplemental Security Income, veterans’ pensions, Aid to Families with Dependent Children | |

| Medical care | Medicare |

| Private disability insurance | |

| Veterans’ programs | |

| Workers’ compensation | |

| Tort settlements | |

| Medicaid | |

| Direct services | Rehabilitation and vocational education veterans’ programs |

| Services for persons with specific impairments | |

| General funded programs (e.g., food stamps, developmental disabilities, blind, mentally ill) | |

| Employment assistance programs (i.e., comprehensive employment training program) |

From Berkowitz M, Hill MA: Disability and the labor market: an overview. In Berkowitz M, Hill MA, editors: Disability and the labor market: economic problems, policies, and programs, New York, 1989, ILR Press, with permission.

The physiatrist has an important supportive role in initiating referrals to the corrective programs. These programs are in keeping with the philosophy of rehabilitation, which is to maximize individual functioning and lessen disability.

Public Disability Policies

Public policy in the United States has begun to recognize that many barriers to integration faced by persons with disabilities are the result of discriminatory policy and practices. Some also have the view that disability is an interaction between an individual and the environment. This has played a fundamental role in shaping public policy toward disability during the past 20 years. Since the late 1960s, Congress has passed a series of laws aimed at enhancing the quality of life for persons with disabilities. These laws have mandated that housing and transportation be accessible, that education for children with disabilities be appropriate, and that employment practices be nondiscriminatory.1,10,47

Three legislative actions deserve to be highlighted. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 extended civil rights protection to persons with disabilities. This legislation included antidiscrimination and affirmative action in employment. The Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1978 broadened the responsibility of the Rehabilitation Services Administration to include independent living programs, and created the National Council of the Handicapped (the National Council of the Handicapped became the National Council on Disability in January 1989). The capstone of this legislative tradition is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. This legislation established a clear and comprehensive prohibition of discrimination based on disability.10,45,47,50

Table 35-5 reviews the prominent federal disability laws.

| Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 | Prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in employment, state and local government, public accommodations, commercial facilities, transportation, and telecommunications |

| Telecommunications Act of 1996 | Require manufacturers of telecommunications equipment and providers of telecommunications services to ensure that such equipment and services are accessible to and usable by persons with disabilities, if readily achievable |

| Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 | Prohibits housing discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, disability, familial status, and national origin |

| Air Carrier Access Act of 1986 | Prohibits discrimination in air transportation by domestic and foreign air carriers against individuals with physical or mental impairments |

| Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act of 1984 | Attempts to ensure polling places across the United States to be physically accessible to people with disabilities for federal elections; this law also requires states to make available registration and voting aids for disabled and elderly voters |

| National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (Motor Voter Act) | Attempts to improve the low registration rates of minorities and persons with disabilities that have resulted from discrimination; all offices of state-funded programs that are primarily engaged in providing services to persons with disabilities are required to provide all program applicants with voter registration forms, assistance in completing the forms, and to transmit completed forms to the appropriate state official |

| Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act | Authorizes the U.S. Attorney General to investigate conditions of confinement at state and local government institutions such as prisons, jails, pretrial detention centers, juvenile correctional facilities, publicly operated nursing homes, and institutions for people with psychiatric or developmental disabilities |

| Individuals with Disabilities Education Act | Requires public schools to make available to children with disabilities a free appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment appropriate to their individual needs |

| Rehabilitation Act of 1973 | The Rehabilitation Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in programs conducted by federal agencies, in programs receiving federal financial assistance, in federal employment, and in the employment practices of federal contractors |

| Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 | Requires that buildings and facilities that are designed, constructed, or altered with federal funds, or leased by a federal agency, comply with federal standards for physical accessibility |

From U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division: A guide to disability rights laws, September 2005.

Vocational Rehabilitation

The objective of vocational rehabilitation is to allow persons with physical disabilities to engage in gainful employment. Historically, formal vocational rehabilitation services were instituted to provide returning World War II veterans with disabilities assistance in obtaining suitable occupations.47

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 authorized federal funding for state rehabilitation agencies to provide a variety of services to qualified persons with disabilities. The federal government supplies 80% of the funding for state vocational rehabilitation agencies, whereas the states must provide the remaining 20%. State agencies administer the programs under the Rehabilitation Services Administration in the Department of Education. The intent of the Rehabilitation Act was to provide services to persons with disabilities, with emphasis placed on serving those with more severe disabilities (General Accounting Office testimony).46 State agencies are usually located in the state division or bureau of vocational rehabilitation. The state division provides direct services and also refers individuals to private rehabilitation agencies and training programs when indicated.

Aptitude Matching Versus Work Sample

Vocational testing is performed to assess the client’s level of general intelligence, achievement, aptitudes, interests, and work skills. Formal testing consists of administering a battery of paper-and-pencil standardized tests, examples of which are listed in Table 35-6. This type of approach is known as aptitude matching. It determines the client’s aptitudes or traits in the areas of general intelligence, visuospatial perception, eye–hand coordination, motor coordination, and dexterity. Performance on the tests is compared against a list of essential aptitudes, grouped by occupation, in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles published by the Department of Labor.26 When a client’s aptitudes match a particular occupation, a job search is undertaken by the counselor.

Table 35-6 Tests Administered by Vocational Rehabilitation Counselors or Neuropsychologists

| Test | Type |

|---|---|

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised | Intelligence |

| General Aptitude Test Battery | Aptitude |

| Differential Aptitude Test | Aptitude |

| Wide Range Achievement Test | Achievement |

| Strong–Campbell Interest Inventory | Interest |

| Career Assessment Inventory | Interest |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory | Personality |

| Halstead–Reitan | Cognitive evaluation |

| Luria–Nebraska | Cognitive evaluation |

A work sample approach is often used in conjunction with aptitude batteries. The work sample approach measures general characteristics such as size discrimination, multilevel sorting, eye–hand–foot coordination, and dexterity. The Valpar Component Work Sample Series (VCWSS) is a good example of the work sample approach. The VCWSS uses complex work apparatus to measure almost exclusively motor responses. Less focus is applied to general intelligence, aptitude, and academic performance. Work samples can also evaluate the type of “work group” in which the client is most skilled. This simulated work requires performance of a series of tasks, such as drill press operation or circuit board or bench assembly.26

On-the-job training requires job development. The counselor or the client explores community business resources to develop suitable positions. Tax incentives for potential employers can help convince industry to offer training. Sliding-scale wages can be arranged to assist in developing positions. For example, the state rehabilitation agency might fund 100% of salary for 3 to 6 months. The employer gradually assumes that responsibility over the next 3 to 6 months as the new employee becomes trained. Many employers want to keep the employees they have trained, but some prefer to act in the capacity of trainers for a series of persons with disabilities. In this case, the counselor still has the task of placing the newly trained people.

Sheltered Workshops

One of the problems with the traditional approach of the vocational rehabilitation agency has been its poor record of success, especially for persons with severe disabilities. Forty-five percent fewer people were successfully vocationally rehabilitated in 1988 than in 1974, despite increased financial support and larger numbers of persons with disabilities.47 A 1987 General Accounting Office survey found that of SSDI recipients receiving vocational rehabilitation, less than 1% left the SSDI rolls.37 Although now a bit better, these numbers remain small. A 2007 General Accounting Office report to Congress noted that by 2005 an average of 7% of Social Security Administration (SSA) beneficiaries had left the roles after vocational rehabilitation. The International Center for the Disabled (ICD) survey reported that although 60% of persons with disabilities knew about vocational rehabilitation services, only 10% took advantage of those services. Of those using the services, more than 50% believed they were not useful in securing gainful employment.14

A sheltered workshop is a “public non-profit organization certified by the U.S. Department of Labor to pay ‘subminimum’ wages to persons with diminished earning capacity.”17 More than 5000 of these workshops exist, including Goodwill, Inc., serving approximately 250,000 persons with disabilities. This form of employment serves persons with severe disabilities, including limited vision, mental illness, mental retardation, and alcoholism. Although sheltered workshops provide job experience and income, critics report that sheltered workshops rarely lead to competitive, integrated employment. People with severe disabilities can be competitively employed in the community through the use of some modern strategies, as outlined below.

Other Programs for Employment

Transitional and Supported Employment

Two newer strategies for returning disabled persons to competitive, integrated gainful employment are transitional and supported employment. Transitional employment consists of providing the job placement, training, and support services necessary to help persons move into independent or supported employment.39 Independent employment provides at least a minimum wage to the employee and requires no job subsidy or ongoing support. Transitional employment is a short-term provision of services for a period not to exceed 18 months, and culminates in an independent or supported employment position.

Supported employment has been used as a successful strategy for placing or returning the most severely disabled individuals to competitive, integrated community employment. It requires ongoing support after placement, including counseling for the employee and co-workers, and assistance with transportation, housing, and other non–work-related activities. It began as an alternative to sheltered workshops and day programs and has grown to have modest federal funding and broad community support. This support comes from groups of persons with disabilities, state vocational rehabilitation agencies, and state departments for the developmentally disabled. This concept became a permanent part of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 with the passage of the 1986 amendments and additional regulations published in June 1992.51

Supported employment is meant to provide ongoing support for persons with severe disabilities. According to Wehman et al.,51 it must meet five critical criteria (Box 35-2). The first is that all interventions, including training, placement, and counseling, be provided at the job site rather than in a therapy room or vocational school. Second, the intervention and services are provided on a permanent or long-term basis as the individual requires them. Third, these programs are intended to serve only those individuals with the most severe disabilities who have been unable to enter the competitive labor market with their disability in the past. Fourth, the work provided is real and meaningful for the employee, and compensation is received equal to that of an able-bodied co-worker for the same duties. Fifth, work must occur in an integrated setting allowing interaction with co-workers without disabilities.51

BOX 35-2 Critical Criteria for Supported Employment

From Wehman P, Sherron P, Kregel J, et al: Return to work for persons following severe traumatic brain injury: supported employment outcomes after five years, Am J Phys Med Rehabil 72:355-363, 1993, with permission.

Four models of supported employment have been developed. The enclave model consists of a small group of persons with disabilities working together at an integrated job site. The mobile work crew model uses a small group of workers who travel from job to job and offer contractual services under the direction of a supervisor. The small business or entrepreneurial model creates a new small business that produces goods or services using both workers with disabilities and those without them. The most frequently used model is the job coach with individual placement.17

Job coach intervention time can be very significant (almost 8 hr/day) initially. Wehman et al.51 conducted a 5-year study of supported employment for persons with traumatic brain injury. They documented an average requirement of 249.1 hr/person of job coach time over 6 months. The job coach’s intervention time decreased steadily with time on the job to an average of less than 3 hr/wk/person after 30 weeks of employment.

Disincentives for Vocational Rehabilitation

Public and political opinion has changed in recent years regarding the ability of persons with disabilities to work. Both persons with disabilities and policy makers have demonstrated a desire to return persons with disabilities to gainful employment. Statements of past presidents of the United States reflect the change of opinion. In 1973, Richard M. Nixon spoke concerning the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, saying it “would cruelly raise the hopes of the handicapped [for gainful employment] in a way that we could never hope to fulfill.”17 Advocacy by groups for the rights of persons with disabilities has achieved significant policy changes, as reflected by Ronald Reagan’s November 1983 proclamation of the Decade of Disabled Persons, in which the economic independence of all people with disabilities was to become a “clear national goal.”39 With the passage of the ADA in July 1990, George H. W. Bush proclaimed the “end to the unjustified segregation and exclusion of people with disabilities from the mainstream of American life.”17

Incentives for Vocational Rehabilitation

Incentives for the Individual

Since the inception of the SSI program in 1974, only a small number of beneficiaries have been employed. Social Security bulletins note that in 1976 approximately 71,000 beneficiaries were working. By 2006, that number had increased to 349,000. During the same years, the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) blind and disabled caseload increased from 2 million to 6.1 million. It appears that in 2006 about 6% of those who received an SSI payment were employed. Because these low numbers have been believed to reflect actual disincentives built into the current SSI payment system, a number of incentive programs have been implemented.20

Incentive programs are applicable depending on whether the person with a disability receives SSDI or SSI benefits, or both. SSDI work incentives are discussed first. Table 35-7 presents a summary of the terminology and abbreviations for easy reference. Additional references are given here for those wanting more detailed information.∗

Table 35-7 Summary of Incentives for the Individual Receiving Benefits to Enter Work Activities

| Incentive | Details |

|---|---|

| Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) | Disability benefits program based on medical disability and a worker’s earnings covered by social security (Title II—Social Security Act) |

| Supplemental Security Income (SSI) | Disability benefits program based on medical disability and the amount of income a person receives (Title XVI—Social Security Act) |

| Trial work period (TWP) | Allows trial return to work to test work ability without affecting benefits (SSDI) |

| Substantial gainful activity (SGA) | Performance of significant and productive physical or mental work for pay or profit (>$700/month for nonblind [SSDI and SSI] and $810/month for blind recipients [SSDI only]) |

| Extended period of eligibility | Allows reinstatement of cash benefits without a waiting period if the worker’s earnings fall below SGA level within 36 months after TWP (SSDI) |

| Impairment-related work expenses | Allows costs for certain items to be deducted from earnings when figuring SGA level (SSI and SSDI) |

| Earned income exclusion | Allows exclusion of a portion of earned income when figuring an individual’s monthly benefit (SSI) |

| Blind work expenses | Allows work-related expenses when figuring benefits (SSI) |

The initial incentive toward return to work involves a trial work period (TWP). The TWP lets people test their ability to work or run a business without affecting their benefits. This TWP maintains cash benefits for 9 months (not necessarily consecutive) of trial work in a 60-month period. During this period, beneficiaries can earn up to $530 per month.4

On completion of the TWP and continued employment at or above the substantial gainful activity (SGA) level, benefits continue to be paid for an additional 3 months and are then terminated.27,42,43 Any earnings from work below the monetary limit of the SGA level described in Table 35-7 are excluded when figuring monthly benefit amounts. The SGA dollar amount was increased in 1999 from $500 to $700, and a formula was adopted to link this amount in the future to the national average wage index.4

The extended period of eligibility (EPE) is a period of 36 consecutive months during which cash benefits can be reinstated if, during that period, the individual’s earnings fall below the SGA level. If the individual is unable to maintain earnings at the SGA level, benefits resume automatically and no waiting periods are required. Benefits cease at the end of the EPE, but Medicare continues for an additional 3 months.27,42,43 The elimination of a second waiting period for both cash benefits and Medicare benefits is also an incentive to perform a trial of work.

Under certain circumstances, the person might be able to participate in a Medicare “buy-in.” The client must have completed both the TWP and the EPE. In addition, the extended 3 months of Medicare benefits must have passed. Once these conditions are met, Medicare A and B coverage can be purchased. This medical coverage is for those who cannot otherwise obtain health insurance because of preexisting conditions.27 In March of 2010, President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act. This law includes the Pre-Existing Insurance Plan. When implemented, this plan is inteded to provide a new coverage option to individuals who have been uninsured for at least 6 months because of preexisting condition.

Another major incentive program for those receiving SSDI or SSI is for impairment-related work expenses. This allows the cost of certain items and services to be deducted from earnings when determining the SGA level. Examples include attendant care, medical devices, equipment, and prostheses.27

For those persons with disabilities receiving SSI benefits, a different, but often similar, set of incentives applies. These incentives provide SSI recipients with assurances that working will not disadvantage them. Section 1619 of the Social Security Act was made permanent by the Employment Opportunities for Disabled Americans Act passed in November 1986. The incentive of Section 1619 allows receipt of SSI cash benefits, even though earned income exceeds the SGA level. Cash benefits are calculated using the earned income exclusion discussed below. Medicaid benefits continue as an additional incentive even after wages become high enough to cause cessation of SSI cash benefits, provided their continuation is needed to allow the recipient to maintain employment.27,42,43

The earned income exclusion allows most of a recipient’s earned income to be excluded, including pay received from a sheltered workshop or day activity center, when figuring the SSI monthly amount.37 “Blind” work expenses is an incentive that allows a person who has visual impairment to pay for work expenses, such as visual aids, guide dogs, or Braille translations. These allowable expenses are then excluded when calculating benefit amounts.

Another incentive program, Plans for Achieving Self-Support, allows an SSI recipient to set aside income and resources necessary to achieve a work goal.31,42,43

Incentives for Industry

Government policy makers have made various attempts to offer tax incentives to business and industry. These incentives have mainly been directed at making the workplace accessible. Section 190 of the Internal Revenue Code, enacted in 1976 and revised by the Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1990, allows a set amount per year to be deductible for any expenses incurred in barrier removal (making a business or public transportation accessible).34

The Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1990 (which was passed 3 months after the ADA) allows an “access” tax credit with Section 44 of the Internal Revenue Code for small businesses. It allows credit against income taxes for eligible expenditures (auxiliary services for the disabled employee and aids are covered). This access credit is allowed only for expenses incurred for the purpose of enabling a business to comply with the ADA.34

Tax credits have also been used as incentives to encourage hiring of target groups, including the “hard core” unemployed: persons with disabilities and the homeless. The Targeted Jobs Tax Credit (TJTC), originally enacted in 1978, is meant to encourage employers to hire members of these groups. It provides a tax credit for targeted persons, including those persons receiving SSI benefits and vocational rehabilitation referrals (both groups containing large numbers of persons with disabilities). This credit only provides benefits to an employer for 1 year per employee. Many employers use the credit as a windfall; that is, hiring anyone they want and later checking to see whether the new employee falls into a targeted group. This practice is called “retroactive certification.”34

The TJTC has, unfortunately, not been particularly useful in increasing the number of disabled people hired. In fact, legislative incentives in general have not been very successful in achieving the goal of vocationally rehabilitating persons with disabilities. Ongoing efforts in Congress, however, are working to improve the incentives for persons with disabilities to return to work. For example, the Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 (S.331) provides adequate and affordable health insurance when a person on SSI or SSDI goes to work by expanding Medicaid options for states and by continuing access to Medicare after returning to work. It encourages SSDI beneficiaries to return to work by ensuring that cash benefits remain available if employment proves unsuccessful. An expedited eligibility process is proposed for SSDI beneficiaries who lose benefits because of work and need reinstatement of benefits later. A “ticket” program would provide a new payment system for SSDI and SSI beneficiaries for employment services. It reimburses vocational rehabilitation, training, and employment service providers a portion of benefit payments saved when the beneficiary earns more than the SGA level, currently $700 per month ($1000 for blind beneficiaries).4,19 This program originally called for sanctions (deductions against social security benefits or suspension of SSI benefits) for refusal of vocational rehabilitation, but this was eliminated as of January 1, 2001.5

Approximately 80% of SSI recipients work before applying for SSI, and 20% work after they start receiving payments.35 Scott Muller of the Social Security Administration performed a retrospective analysis of a cohort of more than 4000 people who were initially entitled to benefits.27 Approximately 10% worked during the initial period of entitlement. Of those, 84% were granted a TWP, and of that group, more than 70% completed the TWP. More than 50% did not leave the rolls as a result of their efforts. Less than 3% had benefits terminated as a result of return to work.24

It is clear from the research conducted by the Social Security Administration that legislating incentives is not the complete answer to rehabilitating persons with work disability. Potential employers and persons with disabilities alike must take the initiative. But the search for feasible means to return work-disabled persons to work is well worth it. The General Accounting Office estimates that removing even 1% of disabled beneficiaries from the SSDI and SSI programs each year would result in estimated lifetime savings of $3 billion.36

Disability Prevention

Secondary prevention is aimed at early identification and treatment of a pathologic condition and reduction of risk factors for disablement. For persons with disabilities, there are many opportunities for preventing impairment from limiting one or more activities. The ameliorative and corrective programs discussed above, including vocational rehabilitation strategies, are aimed at reducing activity limitation. These programs have been effective not only in returning the unemployed person to work, but also in preventing job loss in those workers with a disability.2 Interventions in medical rehabilitation focused on the enhancement of activity, such as provision of assistive technology, can be considered secondary prevention.

The General Accounting Office has studied return-to-work strategies used by Germany and Sweden, and recommends that intervention occur as soon as possible after an actual or potentially disabling event to promote and facilitate return to work. Because the current SSI benefit structure in the United States includes a lengthy application process, and then benefits linked to full, permanent disability only, intervention often is only offered long after an applicant has been removed from the workforce—a situation numerous studies have shown to significantly decrease the chance of a successful return to the workforce.36

Tertiary prevention focuses on arresting the progression of a pathologic condition and on limiting further disablement. For people with disabilities, tertiary prevention is designed to limit the restriction of a person’s participation in some area by the provision of a facilitator or the removal of a barrier.54 Environmental modifications, provision of services, removal of physical barriers, changes in social attitudes, and reform in legislation and policy are tertiary prevention strategies. Medical rehabilitation is traditionally considered a tertiary prevention strategy. The public disability policies, such as the ADA, are also efforts to reduce environmental and social barriers to participation.30,48,54

Considering functioning and disablement as outcomes of interactions between health conditions (disorders or diseases) and conceptual factors (social, environmental, and personal), there are many opportunities for the physiatrist and the medical rehabilitation team to intervene. Rehabilitation interventions aimed at prevention of activity limitation or prevention of participation restriction are secondary and tertiary prevention strategies that push the dynamic model of disablement in the direction of function. Some physiatrists feel a responsibility to be actively involved in therapeutic and public health management of disablement to develop and support policies that encourage improved function.18

Conclusion

The physiatrist is positioned to serve a primary role in the functioning and disablement paradigm. As persons with disabilities become a greater segment of our society, the opportunities for physiatrists’ involvement are expanded. It is the physiatrist’s responsibility to be active in disability prevention, in care and advocacy for persons with disabilities, and in the development of public policy on disablement.

1. Adams P.F., Benson V. Current estimates for the National Health Interview Survey, 1988. Vital Health Stat. 1989;10(173):1-250.

2. Allaire S., Li W., LaValley M. Reduction of job loss in persons with rheumatic diseases receiving vocational rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3212-3218.

3. Anderson T.P. Quality of life of the individual with a disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63:55.

4. [Anonymous]. Federal Register: rules and regulations. 2000;65(251):82905-82912.

5. [Anonymous]. Federal Register: rules and regulations. 2003;68(129):40119-40125.

6. Berkowitz M. The socioeconomic consequences of SCI. Paraplegic News. 1994:18-23.

7. Berkowitz M., Hill M.A. Disability and the labor market: an overview. In: Berkowitz M., Hill M.A., editors. Disability and the labor market: economic problems, policies, and programs. New York: ILR Press, 1989.

8. Colvez A., Blanche M. Disability trends in the United States population 1966–76: analysis of reported causes. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:464-471.

9. Dean, DH, and Honeycutt, T. Evaluating the Long-Term Employment Outcomes of Vocational Rehabilitation Participants using Survey and Administrative Data. Final Technical Report May 26, 2005. Disability Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

10. DeJong G., Lifchez R. Physical disability and public policy. Sci Am. 1983;248:40-50.

11. Goodman N., Stapleton D.C. Program expenditures for working-age people with disabilities in a time of fiscal restraint. Washington, DC: Cornell University Institute for Policy Research; November 2005.

12. Haber L.D. Identifying the disabled: concepts and methods in the measurement of disability. Soc Secur Bull. 1988;51:11-28.

13. Haber L.D. Issues in the definition of disability and the use of disability survey data. In: Daniel L.B., Aitter M., Ingram L., editors. Disability statistics, an assessment: report of a workshop. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990.

14. Harris L. The ICD survey of disabled Americans: bringing disabled Americans into the mainstream. New York: Louis Harris and Associates; 1986.

15. Harvey C. The business of employment: employment after traumatic SCI. Paraplegic News. 1993. pp10-14

16. Haveman R.H., Halberstandt V., Burkhauser R.V., editors. Public policy toward disabled workers: cross-national analyses of economic impacts. New York: Cornell University Press, 1984.

17. Hearne P.G. Employment strategies for people with disabilities: a prescription for change. Milbank Q. 1991;69:111-128.

18. Joe T.C. Professionalism: a new challenge for rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1981;62:245-250.

19. Kennedy E.M., Jeffonds J., Moynahan D.P., et al. The Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999. Senate Bill. 331, Feb 1999.

20. Kenney L. Earning histories of SSI beneficiaries working in December 1997. Soc Secur Bull. 2000;63(3):34-46.

21. Kraus L.E., Stoddard S., Gilmartin D. Chartbook on disability in the United States. Washington: US Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research; 1996.

22. La Plante M.P. The demographics of disability. Milbank Q. 1991;69:55-77.

23. La Plante M.P., Kennedy J., Kaye S., et al. Disability and employment, no. 11. Disability statistics abstract series. San Francisco: University of California; 1997.

24. Lin V.W., Cardenas D.D. Spinal cord medicine: principles and practice New York,. Demos Medical Publishing. 2003.

25. McNeil JM: Current population reports, household economic studies, series P70-61. Washington, US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1994–1995.

26. Menchetti B.M., Flynn C.C. Vocational evaluation. In: Rusch F.R., editor. Supported employment. Sycamore, IL: Sycamore, 1990.

27. Muller L.S. Disability beneficiaries who work and their experience under program work incentives. Soc Secur Bull. 1992;55:2-19.

28. Nagi S.Z. Disability concepts revisited: implication to prevention, appendix A. In: Pope A.M., Tarlov A.R., editors. Disability in America: toward a national agenda for prevention. Washington: National Academy Press, 1991.

29. New Mexico Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. The Economic Impact of the New Mexico Division of Vocational Rehabilitation. New Mexico Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Departmental website; September 2006.

30. Pope A.M., Tarlov A.R., editors. Disability in America: toward a national agenda for prevention. Washington: National Academy Press, 1991.

31. Rigby D.E. SSI work incentive participants. Soc Secur Bull. 1991;54:22-29.

32. Rocklin S.G., Mattson D.R. The Employment Opportunities for Disabled Americans Act: legislative history and summary of provisions. Soc Secur Bull. 1987;50:25-35.

33. Rusk H.A. The growth and development of rehabilitation medicine. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1969;50:463-466.

34. Schaffer D.C. Tax incentives. Milbank Q. 1991;69:293-312.

35. Scott C.G. Disabled SSI recipients who work. Soc Secur Bull. 1992;55:26-36.

36. Sim J. Improving return-to-work strategies in the United States disability programs, with analysis of program practices in Germany and Sweden. Soc Secur Bull. 1999;59(3):41-50.

37. Social Security Administration. Report of Disability Advisory Council: executive summary. Soc Secur Bull. 1988;51:13-17.

38. Symington D.C. The goals of rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:427-430.

39. Thornton C., Maynard R. The economics of transitional employment and supported employment. In: Berkowitz M., Hill M.A., editors. Disability and the labor market: economic problems, policies, and programs. New York: ILR Press, 1989.

40. U.S. Census Bureau. Americans with Disabilities: 2005 Report. Issued. December 2008.

41. U.S. Census Bureau: 2007 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. S1801. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatamainPageServlet?-program= DEC&_submenuId=datasets

42. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social Security Administration: redbook on work incentives. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1992.

43. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social Security Administration. Social Security handbook, ed 13. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1997.

44. U.S. Department of Justice. Civil Rights Division. A Guide to Disability Rights Laws. September 2005.

45. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. U.S. Department of Justice: Americans with Disabilities Act handbook (EEOC-BK-19). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1991.

46. U.S. General Accounting Office. Report to Congressional Requestors: vocational rehabilitation: improved information and practices may enhance state agency earnings outcomes for SSA beneficiaries. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; May 2007.

47. U.S. General Accounting Office. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Select Education, Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives. Vocational rehabilitation program: client characteristics, services received, and employment outcomes. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1991.

48. Vachon RA: Employing the disabled. Issues Sci Technol 1989-1990; winter:44-50. Available at: http://www.ada.gov/guide.htm. Accessed August 8, 2010

49. Vachon R.A. Employment assistance and vocational rehabilitation for people with HIV or AIDS: policy, practice, and prospects. In: O’Dell M.W., editor. HIV-related disability: assessment and management: physical medicine and rehabilitation: state of the art reviews. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1993.

50. Vachon R.A. Inventing a future for individuals with work disabilities: the challenge of writing national disability policies. In: Woods D.E., Vandergoot D., editors. The changing nature of work, society and disability: the impact on rehabilitation policy. New York: World Rehabilitation Fund, 1987.

51. Verville R. The rehabilitation amendments of 1978: what do they mean for comprehensive rehabilitation? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;60:141-144.

52. Wehman P., Sherron P., Kregel J., et al. Return to work for persons following severe traumatic brain injury: supported employment outcomes after five years. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;72:355-363.

53. Wilson R.W. Do health indicators indicate health? Am J Public Health. 1981;71:461-463.

54. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning. Geneva, WHO: Disability and Health; 2001.

55. World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning and disablement: ICIDH-2, the International Classification of Impairments, Activities, and Participation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

56. Yelin E.H., Cisternas M., Trupin L. The economic impact of disability in the U.S., 1997: total and incremental estimates. http://papers.ssrn.com/Sol3/papers.cfm?/abstractid=899927, 2006. Available at Accessed August 8, 2010