Chapter 11. Emerging problems

Outbreaks and deliberate releases – SARS, toxins and biological agents

Unusual illnesses – deliberate release of infectious and chemical agents416

Poisoning with nerve agents421

Key nursing skills in outbreaks and deliberate releases422

How Infection Spreads

• close contact with unrecognised infected persons

• infectious respiratory secretions – cough and sneeze

• true airborne transmission (‘aerosol’)

• faecal and oral transmission

• contact with contaminated body surface (shaking hands)

• touching contaminated external surfaces

The possibility of an outbreak of an unfamiliar infection or of disease caused by bioterrorism cannot deflect the ward staff from basing all their initial management of seriously ill patients on the principle of probability: common things occur commonly. Thus an outbreak of severe pneumonic illness is more likely to be due to Legionella from say a faulty cooling tower (as in a 2003 outbreak in Montpellier) than from SARS or an airborne terrorist release of plague. A patient with progressive paralysis is far more likely to be suffering from the Guillain–Barré syndrome than from botulism, and a haemorrhagic rash more likely to be meningococcal septicaemia than Ebola virus.

Nonetheless, there is an issue of early recognition because, in their initial stages, these rare infections and toxins share clinical features with more commonplace conditions. The fact that deliberate infections and mass poisonings have taken place in recent years means further attacks are likely. Staff should therefore remain vigilant and plans must be in place. Previously, the responses to outbreaks and toxic releases have been characterised by:

• inadequate preparations

• late recognition

• poor communications

It is critical that the most up-to-date information is to hand. Local expertise will be limited, although there is increasing experience with strict respiratory protection through its use in multi-drug-resistant TB. Fortunately, international experience and guidelines are freely available electronically through several important websites (→ further reading p. 424).

There are several basic principles involved.

• An awareness of new threats and the emergence of novel infections/agents

• An appreciation that there will be no previous personal experience with cases

• The need for immediate up-to-date information from the internet

• The need to review protocols and procedures in the light of new information

• The skills of infection control in highly contagious patients

• The need for timely communication

• The rapid involvement of designated staff and resources

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

SARS is uncommon, but it provides an important lesson in how an Acute Medical Unit may have to deal with the emergence of a new and highly infectious disease.

In February 2003, a doctor from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong became ill while staying at a Hong Kong hotel. Twelve other guests became infected, of whom seven had rooms on the same floor. These index cases moved on – spreading SARS to Vietnam, Singapore, Canada, Ireland and the US. By mid-April it had infected almost 3500 people in 27 countries, causing widespread panic. By May 2003, scientists had identified the infecting organism as a coronavirus (now known as SARS-CoV), which is normally an animal virus but which had crossed species to man. By July, the outbreak was over, having infected more than 8000 people with an 11% mortality rate.

SARS is spread like TB or influenza, in droplet form, but in spite of infection control measures, 25% of the cases occurred in exposed healthcare workers.

The implications of making a tentative diagnosis are so profound regarding isolation measures and public health protection that it is vital to be aware of the precise diagnostic criteria (case definition).

Case definition of SARS

Possible case

A patent who is ill enough to be in hospital with a high fever (> 38°C) and coughing, difficulty with breathing or dyspnoea and with chest X-ray changes of pneumonia who, within 10 days before the onset of symptoms:

• has been in an area that has been designated by the World Health Organisation to be a zone of potential re-emergence of SARS (currently mainland China and Hong Kong)

or

• has been in close personal contact with a probable case of SARS

Probable case

• Patients with a clinical diagnosis of SARS (possible cases) in whom preliminary laboratory tests are positive

Confirmed case

• Probable case in whom further tests are positive

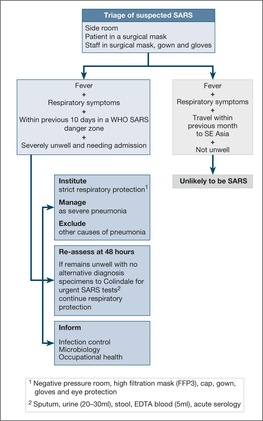

Management of a possible case of SARS

Patients with suspected SARS are likely to be severely ill and have the clinical picture of acute pneumonia. While confirmation of the diagnosis is awaited, they should be treated along conventional guidelines for severe pneumonia, but with the additional need for strict infection control.

Detailed guidance for infection control in possible cases of SARS should be available through a local protocol and can also be found at the Health Protection Agency website.

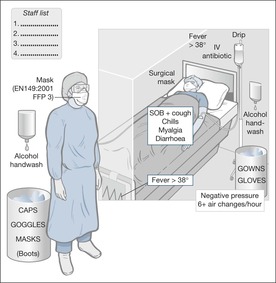

The patient should wear a surgical mask – within the constraints imposed by their oxygen requirements – and should be nursed in a negative-pressure single room. All healthcare workers entering the room must comply with infection control:

• neck-to-heel gowns and gloves – to be left in the room before leaving

• a respirator mask conforming to EN149:2001 FFP3, such as the 3M mask: 1873 V. Staff using an FFP3 mask must be fit tested

• cap and goggles or visor – to be removed, with the mask, once outside the room

• boots

• strict hand washing in alcohol – before and after leaving the room

Surgical masks versus particulate respirators

Surgical face masks are designed to prevent droplet emission and to act as a barrier to splashes of liquid. They will capture microorganisms in the exhaled breath, but do not protect against airborne infection: for this an appropriate respirator is needed. Respirators are high-filtration masks that prevent inhalation of sub-micron sized particles. They do not filter the wearer’s expired air. To be used safely and to maintain a high filtering efficiency, the respirator must be fitted correctly, with a less than 10% leak.

Fig. 11.1 gives an overview of the initial pathway for a potential case of SARS. Fig. 11.2 summarises the strict infection control measures that are required. The clinical management of SARS is the same as for severe community acquired pneumonia, with fluid replacement and i.v. antibiotics. High-flow oxygen, above 6L/min, is to be avoided, as it increases the risk of droplet spread: administer 30–40% oxygen using a Ventimask. Oral prednisolone (40–60mg daily) in severe cases probably improves the prognosis. Daily chest films are essential for monitoring these patients, because the pneumonia characteristically progresses with alarming speed. There is a high chance of the patients needing ventilation – particularly if they are elderly or have co-morbidity. Close liaison will be needed with the ITU, and probably with a designated Regional Centre.

Other Emerging Infections

SARS is only one example of new infectious diseases that have profound implications for Public Health. In August 1999, eight similar cases of encephalitis were admitted to hospitals in the Northern Queens district of New York. Four of the individuals were paralysed and needing ventilation. All eight usually spent their evenings out of doors in the vicinity of breeding sites for Culex mosquitos, which were suspected to be spreading a virus. Subsequent investigations of a substantial number of bird deaths in the area and of the patients identified the offending organism: West Nile Virus. The lessons from the successful recognition of this disease include:

• an awareness of the importance of clustering of cases

• the value of good communication

• excellent cross-professional working

More recently, in 2003, a virulent avian flu virus broke out in South East Asia. The virus, the H5N1 strain of bird flu, crossed the species barrier from domestic duck to man and killed 20 people in Thailand and Vietnam. Many believe that a major flu pandemic from this type of source is inevitable. SARS and influenza spread in the same way, so that similar infection control measures would be required.

H1N1 2009 influenza (Swine flu)

The 2009 Swine flu pandemic typified the challenges of a new viral threat:

• The possibility of an overwhelming number of seriously ill cases. In fact in England between June and November 2009 there were 540,000 cases but only 138 deaths

• The emergence of at risk populations with a higher mortality rate: those over 20 weeks pregnant, those with co-morbidity especially asthma, the morbidly obese and the elderly

• The need to apply assiduously in-patient infection control measures appropriate to a droplet-spread infectious disease

• To ensure that there is early isolation and treatment, but not at the expense of ignoring the possibility of other diagnostic possibilities: community acquired pneumonia, bacterial meningitis and septicaemia

• The role of anti-viral medications: oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) and zanamivir (Relenza®)

Unusual Illnesses – Deliberate Release of Infectious and Chemical Agents

Deliberate Release of Infectious Agents

General principles

The effects of a deliberate release of an infectious or biological agent may be recognised only when cases of unusual illness appear on the Acute Medical Unit. This is particularly likely after a covert release, as there will be no mass Emergency Service response and the presentation of the cases may have a less obvious pattern – the connection between them may not be immediately apparent.

An unusual illness may present in three ways:

• a diagnostic puzzle

• an illness ‘out of place’ – such as a tropical disease with no travel history

• the failure of a ‘conventional’ illness to respond to usual treatment

Obviously an outbreak, or clustering, of such cases has much more significance than a single incident, but in covert deliberate release the cases may be admitted to hospital with no immediately obvious pattern. Ideally, vigilance and awareness should be high at all times, but the likelihood of a deliberate release remains so low that there is a danger that, over time, the possibility is forgotten.

It may therefore be advisable to have named members of the Ward Staff whose responsibility it is to keep themselves up-dated on current risks and infection control measures, to liaise with other appropriate departments and to maintain a file of information on the ward giving relevant protocols, contact details and websites.

There are four important areas in the management of potential cases:

1. Awareness and recognition.

2. Communication.

3. Decontamination and containment.

4. Seek early advice.

Awareness and recognition

There are several warning signs of a potential outbreak:

• the receipt of a prior warning or threat

• people with a similar disease or syndrome presenting at the same time

• a number of cases of unexplained disease or death

• a familiar illness occurring in an unusual setting within a community

• illness affecting a key sector of the community

• a familiar disease with an unusually high death rate

• disease with an unusual geographic or seasonal distribution

• unusual, atypical, genetically engineered, or antiquated strain of agent

• simultaneous outbreaks of similar illness in separate areas

• unusual transmission routes, e.g. by aerosol, food or water

• animal deaths or illness that precedes or accompanies human illness or deaths

• illness only among people in proximity to common ventilation systems

Taking the correct samples for screening for infections and toxins

The samples for screening for infectious diseases should contain at least two sets of blood cultures. Two 10ml samples of clotted blood are also required for serology and biotoxin measurements. Two 10ml EDTA blood samples are needed for sophisticated molecular identification studies. A 20ml sample of urine in a preservative-free bottle should also be sent.

To identify chemical toxins from high-risk cases, ‘Toxiboxes’ are situated in the AED and should be used for handling and transporting samples to the laboratory. The Toxibox has the containers and packaging to send the following samples:

a) 10ml of blood in a plastic lithium tube

b) 5ml of blood in a glass lithium tube

c) 4ml of blood in an EDTA tube

d) 300ml of urine in a preservative-free bottle

The samples require careful handling and they need to be marked ‘high risk’. Each bottle is bagged separately. Blood forms, in separate bags, are attached to each matching bottle. Once the laboratories have been alerted, the samples are delivered urgently, by hand.

Communication

There will have to be excellent lines of communication locally with Occupational Health, Control of Infection, Laboratory Service and, if an outbreak is confirmed, with regional and national bodies. There will inevitably be health and safety priorities that will be the responsibility of the local Occupational Health Department. The local Health Protection Unit, which is part of the National Health Protection Agency, will co-ordinate other aspects of management. This will include informing the police of a suspected outbreak, obtaining expert medical opinions and overall incident control.

Decontamination and containment

The principles are to prevent further harm, to optimise treatment and, of paramount importance, to protect the healthcare staff from harm (if there is any doubt, action must always be taken to protect the staff). For outbreaks in which biological agents are involved, the principle is the adoption of infection control – single rooms, the use of Universal Precautions and, when suspicion is high, specialised respiratory protection.

Universal Precautions

It is not always possible to identify people who may spread infection to others, therefore precautions to prevent the spread of infection must be followed at all times. These routine procedures are usually called ‘Universal Precautions’, and are designed to prevent exposure to potentially infectious blood and body fluids, and to avoid injury by sharp objects.

• Practice good basic hygiene, with regular hand washing

• Cover wounds or skin lesions with waterproof dressings

• Avoid contamination of person and clothing with blood/body fluids

• Disposable gloves and aprons should be worn when attending to dressings, performing aseptic techniques or dealing with blood/body fluids

• Handle and dispose of sharps safely

• Avoid puncture wounds, cuts and abrasions in the presence of blood

• Avoid using sharps if possible

• Protect eyes, mouth and nose from blood splashes

• Know what to do if there is a sharps injury or blood-splash incident

• Clear up blood spillages promptly and disinfect surfaces

• Dispose of contaminated waste safely

• Know how to deal with soiled linen

• Clean, disinfect and sterilise equipment as appropriate

Specialised respiratory protection

Where there is a risk of the airborne spread of serious infection (e.g. MDTB, SARS, viral haemorrhagic fever), strict respiratory precautions are needed to minimise the risk to staff:

• negative pressure rooms with 6–9 air exchanges per hour

• staff wearing gloves, disposable gowns, caps, boots and eye protection

• high-specification masks

• ammonia, phenol and alcohol-based disinfectants

• hourly surface and floor wipes with diluted bleach (1 in 49 dilution of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite)

• alcohol-based hand washes

• initial visiting restrictions

• all gowning and de-gowning carefully supervised:

— gowns and gloves left inside room

— eye protection, mask and cap left outside

Seek early advice

It is of critical importance to maintain a list of up-to-date websites and contact telephone numbers on the Acute Medical Unit.

Poisoning With Biological Agents

Examples of potential pathogens and initial symptoms

This section gives a brief clinical overview of what experts believe to be the most likely terrorist agents. Websites are available for more detailed information.

Anthrax

Influenza-like symptoms followed 2–4 days later by the rapid development and progression of severe respiratory failure and shock. Mortality rates in inhalation anthrax are extremely high, but specific treatment combines ciprofloxacin, vancomycin and rifampicin. Steroids may also help.

Plague

Severe myalgia, sore throat and headache merging into a severe pneumonic illness with copious bloody sputum. Specific treatment is with gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and doxycycline.

Botulism

The patient remains alert, with no sensory loss, but develops a rapidly descending flaccid paralysis due to blockage of nerve impulses to the muscles. There is no fever. Specific treatment is with an antitoxin, but the key is supportive care, which often includes ventilation.

Smallpox

Two to three days of severe fever, headache and malaise, followed by a deeply seated rash spreading and progressing from the mouth and face to the trunk, limbs, palms and soles. Treatment is supportive. Specific treatment is probably ineffective, but the antiviral drug cidofovir can be tried.

Tularaemia

A pneumonic illness with flu-like features or a septicaemic illness with severe shock. Specific treatment is with gentamicin.

Ebola virus

Fever, abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea followed by bleeding from the nose, the gastrointestinal tract and into the skin. Treatment is supportive.

Lassa fever

Fevers, shivering attacks and severe tonsillitis, followed by disturbed consciousness level, respiratory distress and abdominal distension. Treatment is supportive.

Table 11.1 summarises the features of and responses to poisoning with biological agents.

| A, apron; E, (eye protection) goggles; FFP3, particulate filter respirator for staff (→ SARS, p. 411)/surgical mask for patient; G, gloves; GN, fluid-resistant gown; (H), haemorrhagic rash; HW, hand washing ++ (alcohol); SR, side room, which should be at negative pressure; SR*, side room in a designated centre;VHF, viral haemorrhagic fevers (Lassa fever, Ebola, etc.) | ||||||

| Disease | First symptom | Severe pneumonia | Clinical picture | Rash | Staff prophylaxis | Control of infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthrax | Fever | Yes | Rapid deterioration over 1–6 days | Yes | Antibiotics | No isolation, G,A, HW |

| Plague | Fever | Yes | Rapid deterioration over 1–6 days | Yes (H) | Ciprofloxacin | SR, G, GN, E, HW, FFP3 |

| Botulism | No | No | Sudden descending flaccid paralysis | No | Not needed | No isolation, G,A, HW |

| Smallpox | Fever | No | Fever ++, systemic symptoms ++, abdominal pain | Yes (H) | Immediate vaccination | SR*, G, GN, E, HW, FFP3 |

| Tularaemia | Fever | Yes | Variable rate of deterioration | Yes | Not needed | SR, G, GN, E, HW, FFP3 |

| VHF | Fever | No | Rapid deterioration, abdominal pain, diarrhoea | Yes (H) | Nil | SR*, G, GN, E, HW, FFP3 |

Poisoning With Nerve Agents

There are five organophosphorous nerve agents, but there is most experience with sarin, which is a highly volatile vapour that acts predominantly after inhalation but is also absorbed through the skin. In the event of a deliberate release, victims should arrive at hospital having already been decontaminated, so that only standard hospital precautions would be necessary for personal staff protection. The Acute Medical Unit would be receiving moderately ill patients, not those in need of immediate ITU care, for whom the main objectives will be antidote administration and the treatment and monitoring of any respiratory difficulties.

Nerve agents act by blocking the enzyme, acetylcholinesterase, which normally works as a break on nerve impulse transmission. The clinical effects are therefore due to an overload of nerve traffic throughout the nervous system. The antidotes – atropine and related drugs – act by unblocking the enzyme and reducing the flow of traffic.

For clinical purposes, the three important effects are due to overactivity in the parasympathetic nerves – the nerves that oppose the sympathetic nervous system – and hence the signs of nerve agent poisoning are the ‘opposite’ of the fight or flight reaction:

Bradycardia – pulse rate of less than 40 beats/min

Bronchospasm – severe wheeze

Bronchorrhoea – excessive airway and lung secretions

This overactivity is reversed by atropine and two related drugs: pralidoxime and obidoxime. Their effectiveness as antidotes can be monitored by the improvement in these three features.

• Overactivity in the brain leads to coma and convulsions. Convulsions can be prevented with diazepam.

The management after initial decontamination can be summarised by ABC:

1. Antidote administration

2. Breathing support

3. Coma and convulsion care

Antidote administration

Atropine is an effective but short-lived antidote that is given intramuscularly every 5min until the pulse rate increases above 80 beats/min. Pralidoxime and obidoxime have a slower onset, but are long acting. When given i.v., they are effective for around 4h. Intravenous diazepam prevents convulsions and other signs of muscular overactivity, particularly muscular twitching.

The front-line emergency services may have already administered antidotes using the Autoject (Combo Pen) L4 A1, which contains a single-dose combination of atropine, pralidoxime and a form of diazepam. It is given intramuscularly into the lateral aspect of the thigh every 5–15min, depending on the improvement in the ‘three Bs’, to a maximum of three doses.

Breathing support

Death from nerve agent poisoning is usually due to respiratory failure. The mainstay of management is based on high concentrations of oxygen, and nasopharyngeal suction to keep the upper airway clear of the excessive secretions.

Signs of improvement will be:

• less wheeze

• an increasing pulse rate

• reduced airway and nasopharyngeal secretions

Coma and convulsion care

This comprises the standard management and monitoring of a reduced level of consciousness, and the immediate treatment of any convulsions with i.v. diazepam.

Key Nursing Skills in Outbreaks and Deliberate Releases

• Core skills in infection control

— Understanding the routes by which infection spreads

— Strict adherence to and proper use of Universal Precautions

• Advanced skills in the use of Personal Protective Equipment

— The use of high-filtration respirator masks, including the use of a fit-test

— Ensuring there is consistency in the use of Personal Protective Equipment by all team members

• Core nursing skills in the assessment of the critically ill patient

— Initial assessment using the generic ABCDE approach

— Monitoring of the critically ill with impending respiratory failure

— Supporting the patient and their family

• Advanced communication skills for nursing patients in isolation

— Dealing with fear and anxiety in a victim of a ‘dreaded’ illness

— Minimising the bars to communication imposed by protective clothing

— Minimising the impact of the illness on the patient’s well-being

• Disease-specific nursing problems

— Ensuring that a system exists for early recognition and immediate infection control

— Minimising high-risk procedures

— Reducing possible transmission from the time of the first clinical encounter

— Designating ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ areas for isolation materials

• Dealing with the individual threat to personal health

— The issue of ‘working quarantine’

— The concept of ‘cohort nursing’ – logging health-care personnel

— Limiting and educating visitors

• Participating in a strong management system

— The best systems for controlling an outbreak are those that have been tested

• Using information systems on the internet

• The supervision and protection of relatives and visitors

Conclusion

From the personal testimony of healthcare professionals involved with the SARS outbreak in China, Hong Kong and Toronto, it is clear that nursing large numbers of critically ill patients with a highly infectious disease places a major burden on the healthcare system. It also presents a huge personal challenge to individual members of staff. Inevitably, if the problem recurs the Acute Medical Units will be in the front line and will have to cope. It is the responsibility of Acute Unit staff to be aware of the current threats and to be up to date on their management: to understand the issues of effective infection control, to institute them the instant any suspicion is raised, and to ensure that health personnel are not put at unnecessary risk. There are many sources of advice once the diagnosis is made, but the key is a high index of suspicion and appropriate levels of vigilance.

Further Reading

Websites

An algorithm for potential cases of SARS and avian flu: http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/avianinfluenza/pdfs/Algorithm.pdf.

Information about specific substances or agents that could be used in terrorist attacks: http://www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/EmergencyPlanning/DeliberateRelease/fs/en.

SARS SARS, Department of Health website: http://www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HealthAndSocialCareTopics/SevereAcuteRespiratorySyndrome/fs/en.

SARS SARS, Health Protection Agency website: http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/Guidelines.htm.

WHO website, Guidance for hospital infection control in SARS: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/infectioncontrol/en/.

Health Protection Agency, Advice concerning infections, chemical hazards and radiation http://www.hpa.org.uk/HPA/.