Emergency Veterinary Medicine

3. They are fearful for their lives

4. Their young are approached too closely

5. They are cornered or otherwise threatened

6. They are protecting their territory

Pretrip Animal Health Considerations

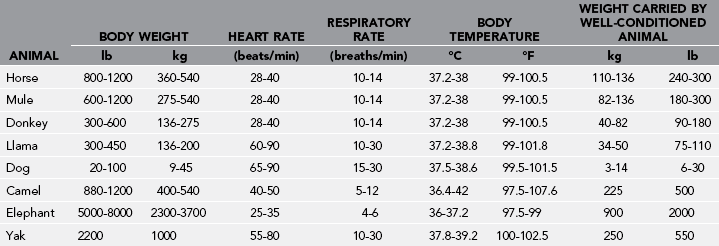

The normal vital statistics of trek animals are itemized in Table 63-1.

Emergency Restraint

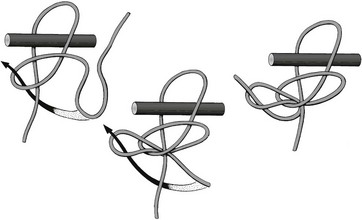

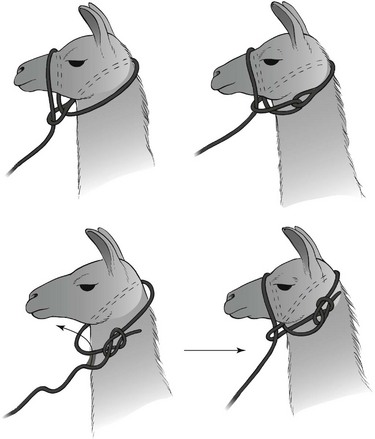

Know how to create a halter tie (Fig. 63-1) and a temporary rope halter (Fig. 63-2).

FIGURE 63-1 Sequence of steps to create a halter tie.

FIGURE 63-2 Temporary rope halters.

Conditions Common to All Species

Skunk Odor Removal

Management of Odor Removal

1. Neutroleum alpha is nontoxic and may be used on clothing and pets..

2. Skunk-Off is nontoxic and nonirritating, even to mucous membranes, and safe to use on pets and clothing.

3. Odormute is available in granular form and easy to transport. It is nontoxic and may be applied to pets and clothing after being dissolved in water.

4. Summer’s Eve douche is an effective product to neutralize skunk spray odor.

Plant Poisoning

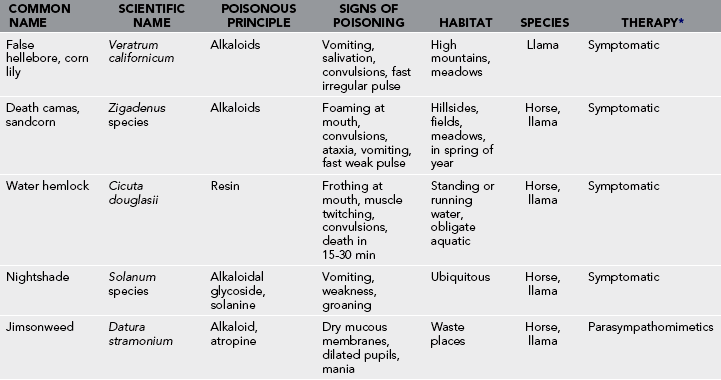

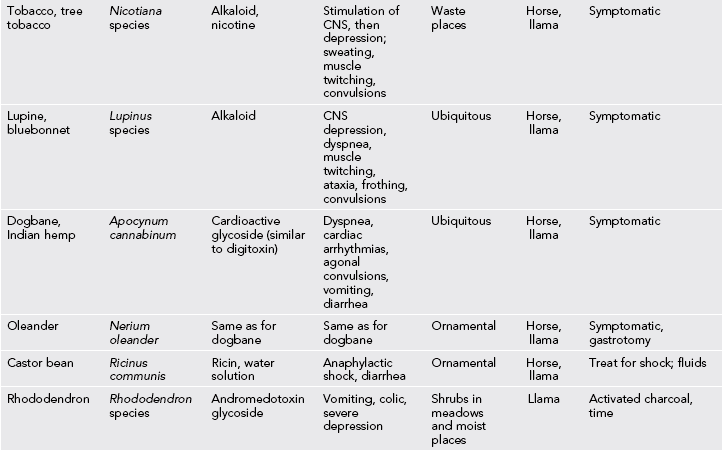

Certain highly toxic plants that grow in wilderness areas of the United States should be recognized as potentially harmful to pack animals (Table 63-2).

Table 63-2

Poisonous Plants That May Affect Horses or Llamas on Trek

*In most cases of poisoning from ingestion of poisonous plants, no specific antidote exists. Victims are treated symptomatically. The critical factor is to empty the digestive tract of the plant material with cathartics, parasympathomimetic stimulation, and enemas. Activated charcoal, given orally, may be of value.

Unique Disorders of Horses, Mules, and Donkeys

Clinical Signs

Laminitis usually develops on both fore feet, but rear feet may also be affected in severe cases. The horse shifts its center of gravity to the hind limbs to minimize pressure on the fore feet, standing with the hind limbs forward under the body and the fore limbs extended in front of the body (Fig. 63-3). The feet are warm or hot to palpation, and there is a pounding digital artery pulse. The horse is reluctant to move.

Management

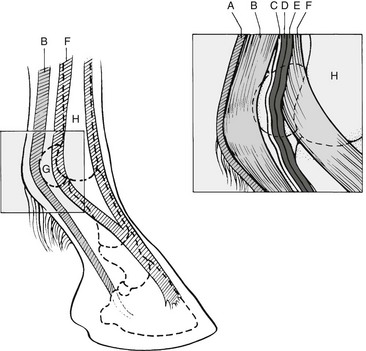

Mild exercise is an important aid in preventing damage to the laminae. The horse should be exercised slowly on soft ground for 10 to 15 minutes every hour for 12 to 24 hours, and then exercise should be stopped. Even slow walking may be quite painful. A low volar nerve block relieves pain and inhibits vascular constriction within the foot. This is accomplished by palpating the pulsating artery on the posterior lateral aspect of the fetlock (Fig. 63-4). The nerve lies posterior to the artery. With a 20- to 22-gauge needle, 3 mL of 2% lidocaine is injected over each nerve. It may be necessary to repeat nerve blocks two or three times daily for several days. Corticosteroids are contraindicated.

Saddle, Cinch, and Rigging Sores

Exhausted Horse Syndrome

Clinical Signs

1. Movements are lethargic, head held low.

2. Facial grimacing and corneal glazing are present.

3. Anorexia is typical, and frequently the horse has no inclination to drink, even though dehydrated.

4. Heart rate, respirations and temperature are elevated. (Heart rates of 150 beats/min are not uncommon after a grueling climb. With 10 to 15 minutes of rest, the heart rate of a conditioned horse should drop below 60 beats/min, whereas in the exhausted horse, tachycardia and tachypnea persist.) Auscultation of the thorax may reveal moist rales and, in extreme cases, frank pulmonary edema.

5. Severe dehydration is the most consistent sign of EHS. (See signs described in Dehydration.)

6. Horses suffering from EHS are prone to colic, which also may occur independently. (See later.)

Colic

Treatment

1. Mild obstructions may be relieved by hydration and administration of a cathartic.

2. Cold water enemas may stimulate sluggish intestinal peristalsis and relieve impaction of the small (terminal) colon.

3. For pain and spasms, give flunixin meglumine, 0.6 mg/kg IM bid.

4. Walk the horse to prevent it from lying down and rolling, which may result in torsion of the intestine.

Unique Problems of Dogs

Gastric Dilatation and Volvulus (“Bloat”)

Treatment

1. Arrange emergent evacuation for definitive surgical treatment.

2. Place an orogastric tube to decompress the stomach, or if unable, decompress the stomach with a large bore IV catheter. This procedure should only be attempted in situations where veterinary care is not immediately available, because of risk for lacerating abdominal organs. The catheter is inserted about a hands’ width behind the last rib in the center of the lateral body wall. The operator will hear and smell gas escaping if the procedure is successful. This can repeated multiple times if necessary while the animal is being transported.

Porcupine Quills

The process is painful, and sedation with diazepam, 0.2 to 1 mg/kg IM or IV, is indicated.

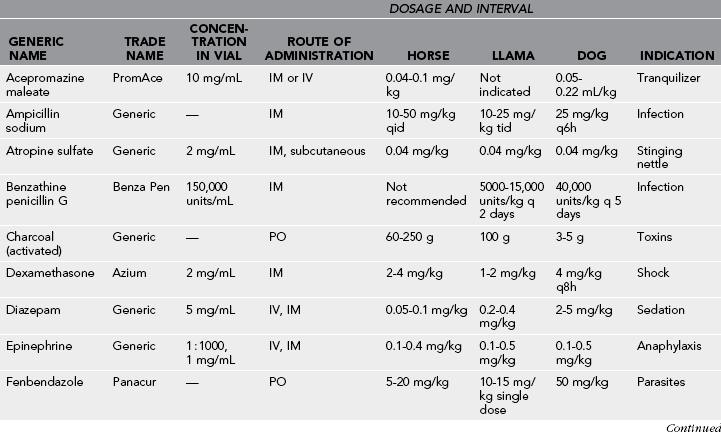

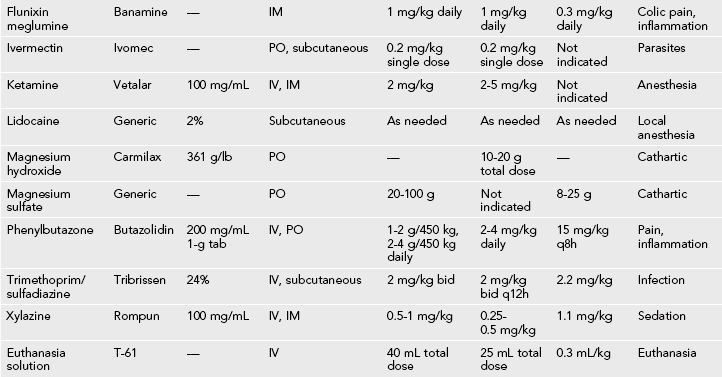

Medication Procedures

A list of medications and indications for their use is provided in Table 63-3. In the horse, intramuscular injections are given in the neck or rump. Subcutaneous injections are given by lifting a fold of skin just cranial to the scapula. IV injections are given in the jugular vein, which is easily distended along the jugular groove on the ventral aspect of the neck.

Table 63-3

Euthanasia

Indications for euthanasia include compound and comminuted fractures of long bones; falling or sliding into inaccessible places from which the animal is unable to extricate itself or trek participants are unable to aid the animal; lacerations exposing abdominal or thoracic organs; head injuries resulting in persistent convulsions or coma; and protracted colicky pain unrelieved by analgesics or mild catharsis. The expedition may carry a bottle of euthanasia solution, which must be given intravenously or intraperitoneally. If firearms are carried, a properly placed bullet to the head produces a fast and humane death. For placement the shooter stands in front of the animal’s head and draws an imaginary line from the medial canthus of each eye to the base of the opposite ear. The shot should be aimed where those lines cross and approximately perpendicular to the contour of the forehead (Fig. 63-5). The tip of the barrel should be no more than 6 inches from the head. A heavy blow to the head at the same location is equally effective. The blow may be administered with the blunt edge of a single-bladed ax or hatchet. A large rock held in the hand may also be used. A less desirable but sometimes expedient method is to sever the jugular vein to allow exsanguination. This would be best used on an animal that is already unconscious.

Figure 63-5 Location for euthanasia blow or shot.

cup [60 mL]), and a dish detergent (1 tablespoon [15 mL]). Mix the peroxide with the water, and then add the baking soda and shampoo. Mix and pour into a squirt bottle/sprayer. This solution may be sprayed onto a dog or horse but should not be sprayed directly into the eyes or nose. The solution should be allowed to remain on the coat for 10 minutes, while being worked into the coat with a gloved hand.

cup [60 mL]), and a dish detergent (1 tablespoon [15 mL]). Mix the peroxide with the water, and then add the baking soda and shampoo. Mix and pour into a squirt bottle/sprayer. This solution may be sprayed onto a dog or horse but should not be sprayed directly into the eyes or nose. The solution should be allowed to remain on the coat for 10 minutes, while being worked into the coat with a gloved hand.