17 Emergencies and procedures

Obstetric emergencies and procedures

Antepartum haemorrhage

Severe antepartum haemorrhage

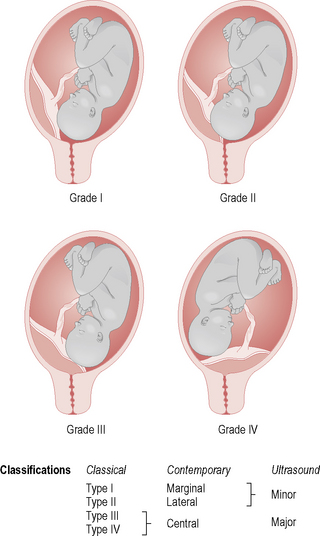

The main causes of severe APH are placenta praevia (Fig. 17.1) and placental abruption. If the patient is collapsed and shocked, then a careful and efficient management protocol must be followed:

• Alert senior medical and midwifery staff.

• Estimate vaginal blood loss from history of pad usage, pooling and other subjective information; assess for signs of hypovolaemic shock, i.e. blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, temperature.

• Auscultate fetal heart and commence continuous monitoring if fetal heart is present.

• Observe for signs of labour.

• Administer oxygen by facial mask.

• Insert intravenous (IV) line using large-bore cannula (may need two lines of access) and commence infusion of colloid (e.g. Gelofusine) ± crystalloid (e.g. Hartmann’s).

• Take blood samples for urgent full blood count, clotting screen, and crossmatch for 6 units of blood.

• Insert indwelling catheter for urinary output measurement.

• Alert anaesthetic registrar, theatre staff and paediatric registrar, and special care baby unit if the fetal heart is present.

Labour ward emergencies and procedures

Unconscious patient

Management

• Basic first aid: left lateral position, maintain airway, oxygen administration via bag and mask if not breathing.

• Assessment of situation and patient, including pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure and fetal heart rate.

• Commence cardiopulmonary resuscitation if there is no cardiac output.

• Establish IV access, obtain blood for full blood count, renal function and electrolytes, serum glucose, liver function, coagulation screen and blood group (crossmatch if suspect haemorrhage).

• Monitor mother and fetus: electrocardiograph and vital signs, cardiotocograph to assess fetal well-being.

• Establish and treat cause of collapse.

• If there is no cardiac output within 10 minutes, consider an immediate caesarean section.

Management

• If oxytocin infusion is in progress, discontinue immediately

• If suspected, alert senior medical staff and arrange immediate delivery by caesarean section

• Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in a patient with a previous uterine scar could be due to uterine rupture. The patient should be managed according to the major obstetric haemorrhage guidelines and may require an exploration of the uterine cavity in theatre, with preparation for a laparotomy and caesarean hysterectomy if necessary.

Uterine inversion

This is inversion of the uterine fundus through the vagina.

Management

• Take blood (including crossmatch for 4 units) and establish IV access

• If the placenta is adherent, do not attempt to separate, but manually replace within the vagina

• Tocolytic therapy (salbutamol 500 μg in 10 ml normal saline IV) may be required

• Hydrostatic method to reduce the inversion (O’Sullivan method) – at least 4 l of warm sterile water connected by IV lines and tubing into the vagina as a douche

• Once uterus is reduced and placenta separated, give ergometrine 500 μg intramuscularly (IM) and then a 40 unit oxytocin infusion

Shoulder dystocia

Management

Alert senior medical and midwifery staff when delivery is imminent. If shoulder dystocia occurs:

• Do not pull hard on the fetal head as this may increase the amount of impaction within the pelvis.

• Position mother in McRoberts position (knee–chest or thighs abducted and hyperflexed on the abdomen supported by an assistant on each side) or on all fours.

• Perform an episiotomy to aid access to fetal shoulders/posterior arm.

• Clear baby’s nose and mouth of mucus.

• Apply firm suprapubic pressure and attempt basic method of delivery of the shoulders.

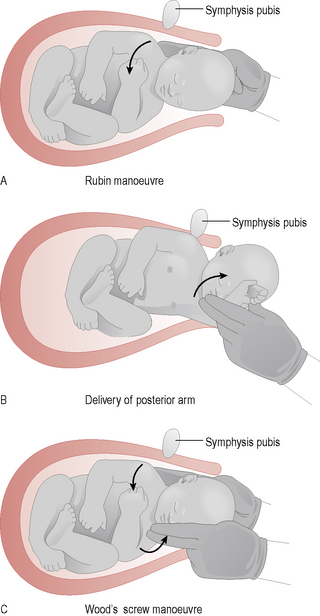

If this fails, attempt delivery of anterior shoulder using the Rubin manoeuvre (Fig. 17.2A):

• Place hand deeply in vagina behind anterior shoulder.

• With next contraction rotate the axis of the shoulders into the more favourable oblique diameter of the pelvis.

• Firm traction is made on the head, deflecting it towards the floor.

• Suprapubic pressure is exerted; this usually succeeds in bringing the anterior shoulder into and through the pelvis.

Extraction of posterior shoulder and arm

If this fails, attempt extraction of posterior shoulder and arm (Fig. 17.2B):

• Place hand deeply into vagina along the curvature of the sacrum and behind the baby’s posterior shoulder.

• Identify posterior arm, follow to elbow. Pass finger into the antecubital fossa to encourage flexion of the elbow joint. Grasp forearm and hand and sweep anteriorly across the baby’s abdomen and chest to deliver the posterior arm.

• Usually, normal head traction will now deliver the anterior shoulder. If not, rotate the baby 180° so that the anterior shoulder is now in the posterior position. It can then be extracted using the same manoeuvres.

Woods’ screw manoeuvres

If this fails, attempt Woods’ screw manoeuvres (Fig. 17.2C):

• Place two fingers from each hand on the baby’s shoulders.

• Rotate the shoulders anticlockwise through 180° to bring the anterior shoulder to a posterior position and draw it lower in the pelvis. The posterior shoulder should deliver under the pubic arch.

• Rotate the shoulders clockwise through 180° to return the former anterior shoulder to the anterior position. It should then also deliver under the pubic arch.

Other delivery methods

Other delivery methods are extremely rare and require consultant management:

• Zavanelli: an alternative, though controversial, delivery method if dystocia is unresolved by more conventional techniques. The procedure involves replacement of the head under anaesthesia and delivery by caesarean section.

• Symphysiotomy: division of the pubic symphysis.

• Cleidotomy: deliberate fracture of the clavicles to reduce the diameter of the shoulders.

Cord presentation/prolapse

Management

• If the baby is alive, aim to expedite delivery immediately.

• Alert senior medical staff, midwife, paediatrician and anaesthetist.

• Stop IV infusion of oxytoxin if in progress.

• Place the woman in the knee–chest, deep Trendelenburg or exaggerated Sims position (with pelvis raised).

• Explain the reason for midwife action to woman and birthing partner.

• With gloved hand use two fingers to replace any loop of cord gently outside the vulva into the vagina to keep it warm and moist. This is not always possible; if the cord cannot be replaced then cover it with warm moist padding.

• Palpate cord for pulsation and ascertain fetal viability.

• Relieve pressure from the cord by pressing up on the presenting part with gloved hand within the vagina until the delivery is imminent.

• If the cervix is greater than 9 cm dilated, the client is multiparous and the presenting part cephalic, the obstetrician may want to expedite delivery by ventouse.

• If the cervix is less than 9 cm dilated an emergency caesarean under general anaesthetic is carried out.

• If the cervix is fully dilated, forceps or breech extraction is the likely outcome.

Repair of episiotomy or vaginal laceration

A spontaneous perineal trauma is classified as:

• First degree: involves fourchette, hymen, labia, skin, vaginal epithelium.

• Second degree: involves pelvic floor, perineal muscle, vaginal muscles.

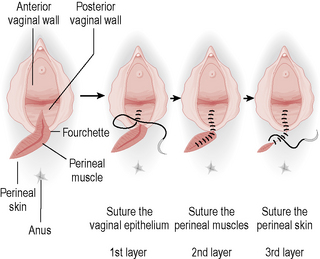

The aim of repair is to achieve adequate haemostasis and obliteration of dead space so as to avoid potential haematoma or infection. Adequate analgesia is essential and, if regional anaesthesia is not established, then local anaesthesia can be used: lidocaine 1% with a maximum dosage of 20–30 ml. The procedure is as follows (Fig. 17.3):

• Good exposure and lighting are essential.

• Apply local anaesthesia if required.

• Appose all tissue involved in the laceration in a correct anatomical fashion after securing the apex, closing all vaginal epithelial lacerations to the fourchette.

• Use a continuous non-locking suture technique with an absorbable synthetic suture.

• Approximate both the superficial and deep perineal muscles involved in the laceration with either a continuous or interrupted suture.

• Repair the perineal skin using either interrupted or, preferably, a subcuticular suture.

• Perform and document both a vaginal and rectal examination on completion of the repair.

• Perform and document a count of instruments, needles and packs used at the end of the procedure.

Repair

• These tears must be carried out by a senior obstetrician. Very severe injury may require the expertise of an anorectal surgeon.

• Good analgesia is essential, i.e. regional or, rarely, general anaesthesia. Good exposure and lighting are essential to allow meticulous inspection. The repair should be carried out in theatre.

• Any obvious faecal contamination should be cleared away and the area thoroughly drenched with an aqueous antiseptic solution.

• In a fourth-degree tear the rectal mucosa should be repaired with an interrupted absorbable suture, ensuring the knots are not within the rectum or anal canal.

• In a fourth-degree tear the internal anal sphincter is a ‘white’ muscle attached to the mucosa. This should be repaired in interrupted sutures. There is recent evidence that 3.0 polydioxane (PDS) may be superior for suturing of the sphincters.

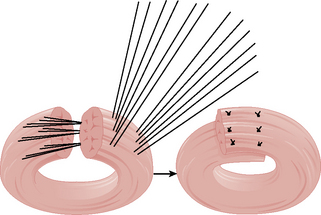

• The external anal sphincter ends need to be adequately mobilized and identified to ensure accurate suture placement.

• The external anal sphincter should be repaired with 3.0 polydioxane suture in either an overlapping or end-to-end technique (Fig. 17.4).

• The remainder of the repair is the same as for an episiotomy or second-degree tear, using an absorbable suture.

• A broad-spectrum antibiotic should be commenced intraoperatively and continued for 1 week. Stool softeners can be considered or advice given regarding avoidance of constipation.

• Advice regarding care of the perineum should be given as soon as possible.

Follow-up

• All patients should be reviewed at 6 weeks.

• Symptoms of flatus or faecal incontinence should alert the obstetrician that further investigations and referral may be necessary.

• If the repair has failed, then appropriate referral for a secondary repair may be considered at least 3 months after primary repair.

• At follow-up there should be a discussion regarding future deliveries and consideration should be given to the use of prophylactic episiotomy.

Retained placenta

• Inform senior medical staff.

• Observe blood loss, pulse and respirations.

• If an epidural is in place and effective, attempts to remove the placenta may take place in the labour ward.

• If there is no epidural, or if it is ineffective, arrange for transfer to obstetric theatre for removal under regional or general anaesthesia.

• Establish IV access and take blood for full blood count and group (consider crossmatch for 4 units).

• Following the procedure continue a Syntocinon infusion (40 units in 500 ml over 4 hours).

Postpartum haemorrhage

Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Management

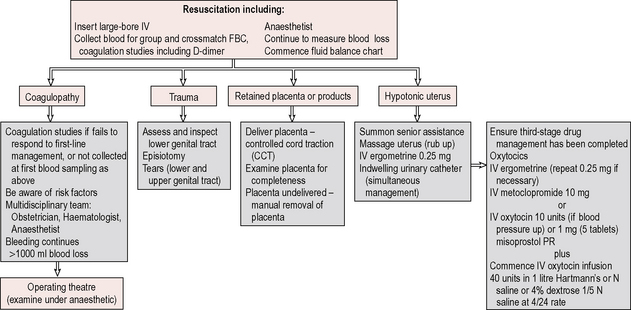

Anticipate the possibility of PPH from recognition of risk factors so that preventive measures can be performed at the earliest opportunity, e.g. ensuring the administration of an oxytocin infusion postpartum in cases of prolonged labour. In the event that haemorrhage occurs (Figs 17.5 and 17.6):

• Alert senior medical and midwifery staff

• Resuscitate and ensure early recognition of cause

• Record maternal observations, pulse, blood pressure, blood loss and fluid balance

• Establish large-bore IV access and take blood for full blood count, coagulation screen and crossmatch for 2–4 units or as necessary.

• Check to ensure placental delivery was complete: if not, the patient may need an examination under anaesthesia.

• Arrange transfer to theatre for manual removal if the placenta has not been delivered.

• Catheterize the bladder and massage the uterus to encourage contraction.

• Establish what oxytocic drug has already been given for the third stage.

• Administer 200–500 μg of ergometrine stat or, if contraindicated, 10 units of oxytocin IV.

• Commence 40 units oxytocin infusion in 500 ml of Hartmann’s over 4 hours if uterus continues to relax.

• Consider vaginal, cervical or uterine laceration if uterus is contracted, but blood loss continues, and prepare for examination under anaesthetic if unable to locate.

• Consider the use of prostaglandin F2α if uterine atony persists, at doses of 250 μg IM or directly into the uterine muscle at 15-minute intervals, to a maximum of 2 grams (8 doses).

Secondary postpartum haemorrhage

Management

• Antibiotics – may need to consider IV cover if there is persistent pyrexia

• Evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC) should be performed by experienced staff as the postpartum, and possibly infected, uterus is easily perforated

• Consider 24 hours of IV antibiotics if infected and bleeding is not too severe, before ERPC.

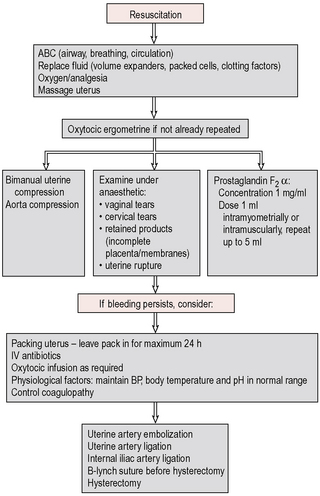

Massive obstetric haemorrhage

This is defined as greater than 2000 ml of blood loss and it is essential to be familiar with the unit protocol and in particular that all relevant staff are notified immediately, including senior obstetric, midwifery, anaesthetic and haematological staff, as well as porters and technicians. A catastrophic obstetric haemorrhage, although difficult to separate from a simple APH or PPH, should be suspected when there is unexplained collapse with signs of shock (Fig. 17.6).

Emergency management

• Alert senior medical (obstetric, anaesthetic and haematology) and midwifery staff.

• Lay the patient on her left side, ensuring an adequate airway, and give oxygen via a face mask.

• Check respiration and pulse.

• If postpartum, rub up a contraction of the uterus and give IV ergometrine 250 μg.

• Set up two large-bore IV access lines with colloid and crystalloid while awaiting blood.

• Take blood for crossmatching, full blood count and platelets, clotting screen, urea and electrolytes.

• Delegate duties to other staff, e.g. midwives to take charge of observations and monitoring of pulse, blood pressure, respirations, fluid balance and blood loss using a high-dependency chart; porters to transport specimens to the laboratory and retrieve at least 6 units of blood from the laboratory.

• In cases of placental abruption the estimation of blood loss is frequently severely underestimated and the need for early and adequate blood transfusion, if necessary with O-negative blood, is vital.

• When haemostasis is controlled, 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma should be given for every 10 units of blood. The consultant haematologist must be involved at an early stage if there is a suspected coagulopathy or need for massive blood transfusion. Inappropriate treatment with anticoagulants may worsen the condition.

• Definitive therapy for the catastrophic haemorrhage must accompany attempts at basic resuscitation. For APH this means urgent delivery; for PPH the usual measures include IV ergometrine, oxytocin infusion or intramyometrial prostaglandin injection. IV tranexamic acid can be useful in the control of bleeding from the lower segment.

• If bleeding cannot be controlled by direct uterine compression, oxytocics and control of a coagulopathy, a laparotomy for a B-Lynch suture, internal iliac ligation or a hysterectomy must be considered.

• Patients who have had a massive blood loss and transfusion will almost certainly have a coagulopathy, and will require intensive-care nursing.

Pulmonary embolus

Caesarean section

Risk assessment

High risk

• Obesity – body mass index (BMI) >30 at booking

• Major current illness, e.g. heart or lung disease, inflammatory bowel disease

• Extended surgery, e.g. caesarean hysterectomy

• Patients with a thrombophilia (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome, activated protein C resistance, protein C or S deficiency).

Severe pregnancy-induced hypertension

Antihypertensive therapy

• Patients may already be on oral treatment with methyldopa, but will require additional treatment with hydralazine if the mean arterial pressure is above l25 mmHg.

• Set up a hydralazine or labetalol infusion in a syringe pump, depending on hospital protocol. Hydralazine may result in a tachycardia >120 beats/min or side effects such as headache and dizziness.

• Any antihypertensive infusion should continue until the patient is delivered and after delivery for at least 24 hours, depending on her response. Thereafter, consider oral antihypertensives if necessary.

Anticonvulsant prophylaxis

Continue infusion until 24–48 hours after delivery, depending on clinical signs.

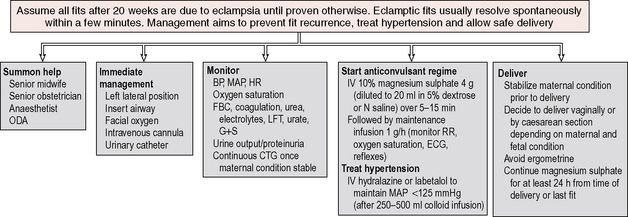

Eclampsia

The three serious complications of eclampsia are:

Management

As in unconscious patient (p. 277), but the main principles are (Fig. 17.7):

Gynaecological emergencies and procedures

Thromboprophylaxis in gynaecological surgery

Risk assessment

High risk

• Minor surgery with a personal or family history of DVT, pulmonary embolism or thrombophilia

• Major surgery with any of the following risk factors:

• Surgery for gynaecological malignancy

• Paralysis or immobilization of the lower limbs

• On hormone replacement therapy or combined oral contraceptive pill preoperatively.