Embryology, Anatomy, Normal Findings, and Imaging Techniques

Embryology of the Neck

This chapter will focus on the embryology of the neck and the oral cavity. The embryology of the orbit, face and sinuses, temporal bone, and ear are addressed in Chapters 4, 8, 9, and 18.

Development of the Mesenchyme

The mesenchyme is derived from three main sources:

1. The lateral plate mesoderm, which forms the laryngeal cartilages and regional connective tissue

2. The neural crest cells, whose migration initiates the formation of the pharyngeal arch skeletal structures and regional bone, cartilage, tendons, and glandular stroma

3. The ectodermal placodes, from which originate the fifth, seventh, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves (CNs)

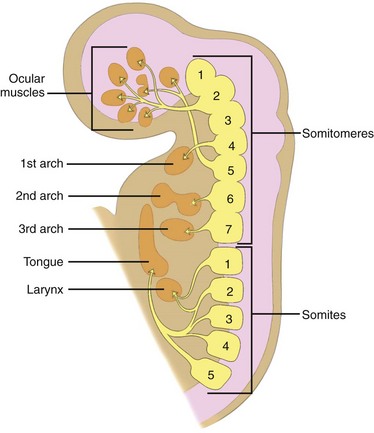

Development of the Mesoderm, Somitomeres, and Somites

After neurulation occurs, the mesoderm subdivides into the lateral, intermediate, and paraxial mesoderm. The lateral mesoderm forms most of the throat and larynx. The intermediate mesoderm does not form any part of the head and neck. The paraxial mesoderm forms the seven somitomeres and 42 to 44 paired somites. The five most rostral somites are involved in the formation of head and neck musculature (Fig. 13-1). The somitomeres and somites form before the development of the branchial apparatus.

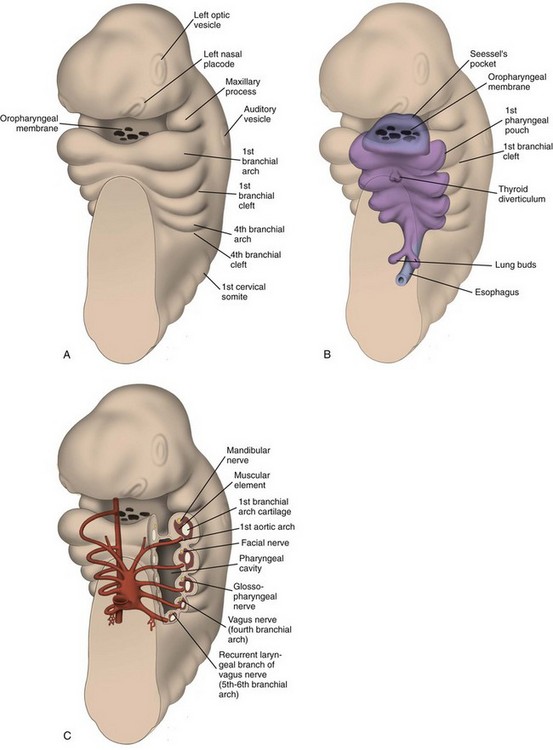

Figure 13-1 Embryology.

A sagittal section shows the relationship of somitomeres and somites and their corresponding derivatives. (From Som P, Curtin H. Head and neck imaging. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2003.)

The contribution of the somitomeres and somites to the formation of muscles and their distinct innervation is unchanged throughout growth and development. Thus although many muscles migrate in location, their nerve supply is maintained and hence their branchial arch origin can always be identified (see Fig. 13-1).

Development of the Branchial Apparatus

Branchial Apparatus and its Contribution to the Structures of the Neck

Branchial Arches: The first branchial arch (Fig. 13-2) is composed of a dorsal segment known as the maxillary process and a ventral segment known as Meckel cartilage or the mandibular process; both involute. The ossification around Meckel cartilage is the precursor of the mandible and the sphenomandibular cartilage in the neck. The muscle derivatives of the first arch are the muscles of mastication (the masseter, pterygoid, and temporalis muscles), the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatine muscles, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the mylohyoid muscle. The trigeminal nerve (CN V) provides motor and sensory innervation to the first branchial arch.

Branchial Pouches: The first branchial pouch does not contribute to the structures of the neck. The second branchial pouch gives rise to the palatine tonsils and tonsillar fossa. The third branchial pouch gives rise to the inferior parathyroids and thymus. The early embryologic connections to the pharynx normally are obliterated. The fourth branchial pouch gives rise to the superior parathyroid glands and the ultimobranchial body, which contains the parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid gland. The fifth branchial pouch degenerates. The branchial clefts do not contribute to any neck structures and are obliterated as development occurs (Tables 13-1 and 13-2).

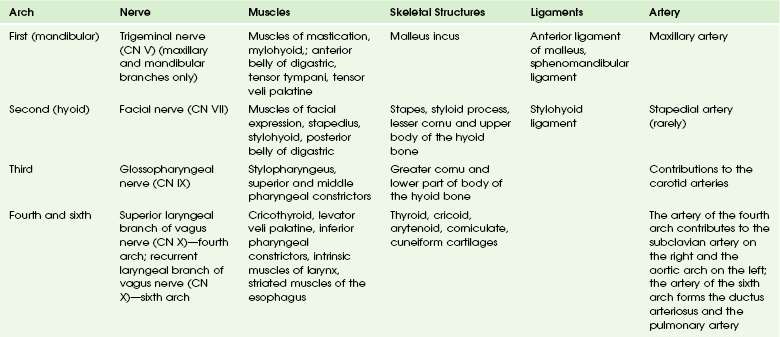

Table 13-1

Derivatives of the Branchial Arches

Adapted from Moore KL, Persaud MG, Torchia MG. Before we are born. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2008.

Table 13-2

Derivatives of the Branchial Pouches

| Pouch | Derivatives |

| First | Eustachian tube, middle ear, portions of mastoid bone |

| Second | Palatine tonsils, tonsillar fossa |

| Third | Inferior parathyroids, thymus |

| Fourth and sixth | Superior parathyroids, parafollicular cells of thyroid |

Adapted from Moore KL, Persaud MG, Torchia MG. Before we are born. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2008.

Anatomy of the Neck

Clinical evaluation and classic anatomy divides the neck into triangles. The largest are the anterior and posterior triangles, which are defined and separated by the sternocleidomastoid muscles. The anterior triangle is further subdivided into the paired carotid and submandibular triangles (separated by the posterior belly of the digastric muscle) and the single midline submental and infrahyoid muscular triangles. The posterior triangle consists of the paired occipital and subclavian triangles, which are separated by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle (Fig. 13-3). The central cavity is divided into the nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and oral cavity.

Figure 13-3 Traditional triangular division of neck spaces.

1. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (SL-DCF), also known as the investing fascia, which defines the masticator, parotid, and submandibular spaces; it also contributes to the carotid space

2. The middle layer of the deep cervical fascia (ML-DCF), also known as the visceral fascia, which primarily forms the buccopharyngeal and pharyngobasilar fascia and the fascia of the tensor veli palatine; it also contributes to the carotid space

3. The deep layer of the deep cervical fascia (DL-DCF), also known as the prevertebral fascia, which forms the perivertebral space and then is subdivided into the anterior prevertebral and posterior paraspinal compartments; the alar fascia is a small component of the DL-DCF and also contributes to the carotid sheath

The advent of cross-sectional imaging enabled a new approach to neck anatomy defined by the concept of dividing the neck into the suprahyoid and infrahyoid compartments, with further subdivision of each compartment into fascially defined spaces (Figs. 13-4 and 13-5). The resultant refined approach to differential diagnosis, combined with the use of surgically and pathologically defined common terminology and nomenclature, has improved communication between radiologists and clinicians.

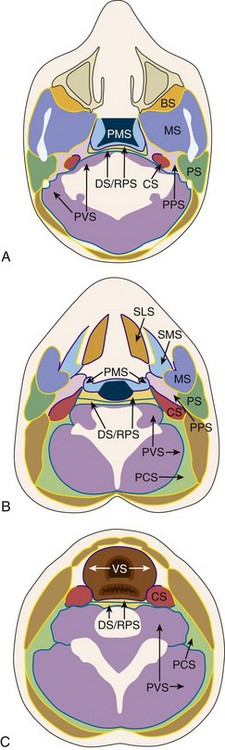

Figure 13-4 Fascial compartments of the neck.

A, Spaces and investing fascia of the suprahyoid neck and the level of the nasopharynx. B, Spaces and investing fascia of the suprahyoid neck at the level of the oropharynx. C, Spaces and investing fascia of the infrahyoid neck. BS, buccal space; CS, carotid space; DS, danger space; MS, masticator space; PCS, posterior cervical space; PMS, pharyngeal mucosal space; PPS, parapharyngeal space; PS, parotid space; PVS, perivertebral space; RPS, retropharyngeal space; VS, visceral space. (Redrawn from Harnsberger HR, Hudgins P, Wiggins R, et al. Diagnostic imaging: head and neck. Salt Lake City, Utah: Amirsys Inc; 2004.)

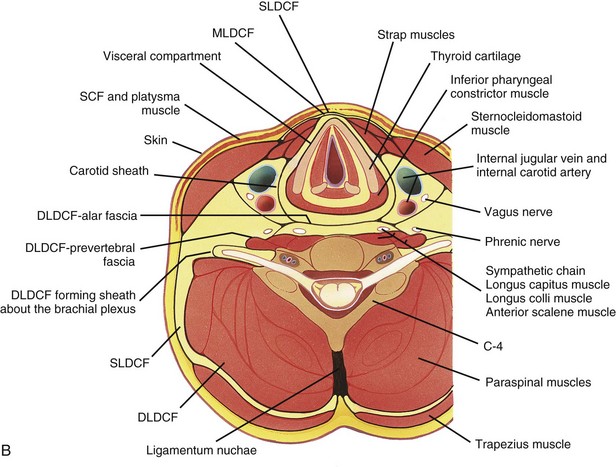

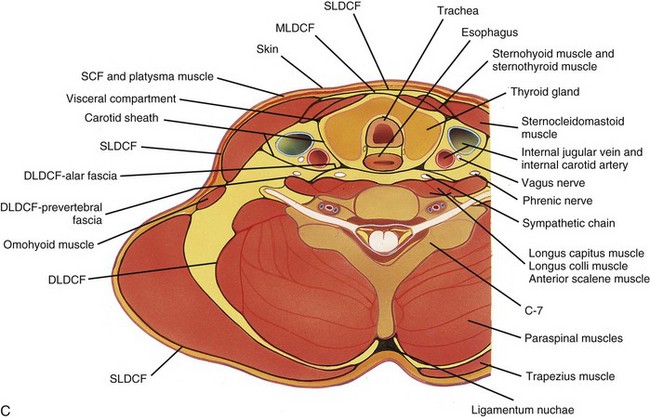

Figure 13-5 Fascial compartments of the neck.

Axial sections at the level of C4 (A), C7 (B), and T1 (C) show the relationship of the investing fascial layers with anatomic structures. (From Som P, Curtin H. Head and neck imaging. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2003.)

The posterior cervical space extends from the mastoid tip to the level of the clavicle. Its superficial boundary is the SL-DCF, and its deep boundary is the deep cervical DL-DCF. It lies posterior to the carotid sheath, posteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and anterolateral to the paraspinal component of the perivertebral space (Tables 13-3 and 13-4).

Table 13-3

Anatomic Spaces of the Suprahyoid Neck

| Space | Contents |

| Pharyngeal mucosal space | Mucosa, minor salivary glands and lymphoid tissue, pharyngobasilar fascia, buccopharyngeal fascia, superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles, levator veli palatini muscle, cartilaginous end of eustachian tube (torus tubarius) |

| Parapharyngeal space (prestyloid parapharyngeal space) | Deep portion of parotid gland, minor salivary glands, pterygoid venous plexus, internal maxillary artery, ascending pharyngeal artery, branches of cranial nerve V3, cervical sympathetic chain and fat |

| Carotid space (retrostyloid parapharyngeal space) | Internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, cranial nerves IX-XII, sympathetic chain, lymph nodes—deep cervical chain |

| Retropharyngeal space | Fat, lymph nodes—retropharyngeal (medial and lateral) |

| Masticator space | Ramus and posterior body of mandible, muscles of mastication—pterygoid, masseter, and temporalis; mandibular division trigeminal nerve (V3)—inferior alveolar and lingual nerves, inferior alveolar vein and artery, pterygoid venous plexus |

| Parotid space | Parotid gland and duct, cranial nerve VII, external carotid artery, retromandibular vein, lymph nodes—intraparotid and periparotid |

| Perivertebral space | Prevertebral muscles, scalene muscles, vertebral artery and vein, brachial plexus, phrenic nerve Vertebral bodies and discs |

Adapted from Som PM, Curtin HD. Head and neck imaging. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2003.

Table 13-4

Anatomic Spaces of the Infrahyoid Neck

| Space | Contents |

| Visceral space | Larynx, hypopharynx and cervical esophagus, trachea, thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, lymph nodes, recurrent laryngeal nerve (branch cranial nerve X), third and fourth branchial apparatus and thyroid/parathyroid anlage remnants |

| Retropharyngeal space | Fat, remnants of third branchial apparatus |

| Carotid space | Common and internal carotid arteries, internal jugular vein, cranial nerve X, sympathetic chain, lymph nodes, carotid body, second branchial apparatus remnants |

| Perivertebral space | Prevertebral, scalene, and paraspinal muscles, brachial plexus, phrenic nerve, vertebral artery and vein Vertebral bodies and discs |

| Anterior cervical space | Extension of submandibular space of suprahyoid neck Composed of fat |

| Posterior cervical space | Cranial nerve XI, spinal accessory nodes, preaxillary brachial plexus, fat |

Anatomy of the Oral Cavity

The sublingual space, which is located superior and medial to mylohyoid muscle and lateral to genioglossus-geniohyoid muscle complex, is not enclosed by fascia (Table 13-5).

Table 13-5

Contents of the Submandibular and Sublingual Spaces

| Space | Contents |

| Submandibular | Submandibular gland, submandibular and submental lymph nodes, facial artery and vein, inferior cranial nerve XII, anterior belly of digastric muscle |

| Sublingual | Hyoglossus muscle (anterior margin), lingual nerve (sensory branches of cranial nerve V3 and the chorda tympani branch of cranial nerve VII), distal cranial nerve IX and cranial nerve XII, lingual artery and vein, sublingual gland and duct, deep portion of the submandibular gland and duct |

Dolinskas, CA. ACR-ASNR practice guidelines for the performance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck [online publication]. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2012.

Harnsberger, HR, Wiggins, RH, III., Hudgins, PA, et al. Diagnostic imaging head and neck, part III. Salt Lake City: Utah: Amirys Inc; 2004.

Jinkins, JR. Atlas of neuroradiologic embryology, anatomy, and variants. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

Ludwig, BJ, Foster, BR, Saito, N, et al. Diagnostic imaging in nontraumatic pediatric head and neck emergencies. Radiographics. 2010;30(3):781–799.

Mafee MF, Valvassori GE, Becker M, eds. Imaging of the head and neck, 2nd ed, New York: Thieme Stuttgart, 2004.

Moore, K, Persaud, TVN. Before we are born: essentials of embryology and birth defects, 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

Mukherji, SK, Wippold, FJ, II., Cornelius, RS, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria neck mass/adenopathy [online publication]. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2009.

Siegel, MJ. Pediatric sonography, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Som, PM, Curtin, HD. Fascia and spaces of the neck. In Som PM, Curtin HD, eds.: Head and neck imaging, 4th ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Som, PM, Smoker, WRK, Balboni, A, et al. Embryology and anatomy of the neck. In Som PM, Curtin HD, eds.: Head and neck imaging, 4th ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Weiss, KL, Cornelius, RS, Greeley, AL, et al. Hybrid convolution kernel: optimized CT of the head, neck, and spine. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(2):403–406.

Wippold, FJ, 2nd. Head and neck imaging: the role of CT and MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(3):453–465.