Chapter 41 Electrical Stimulation

41.2 Electrical Stimulation

(TRANSCUTANEOUS ELECTRICAL NERVE STIMULATION [TENS]; NEUROMUSCULAR ELECTRICAL STIMULATION)

OVERVIEW.

Electrical stimulation (ES) uses alternating or direct current to accomplish various therapeutic aims including (1) to increase strength and endurance of innervated muscle (NMES), (2) to modulate pain (TENS), (3) to reduce edema (HVPC) and enhance healing, and (4) to stimulate denervated muscle (DC). It is also used (5) to deliver transdermal drugs using direct current (see Iontophoresis) and (6) to activate muscles during functional activities (see Functional electrical stimulation).1

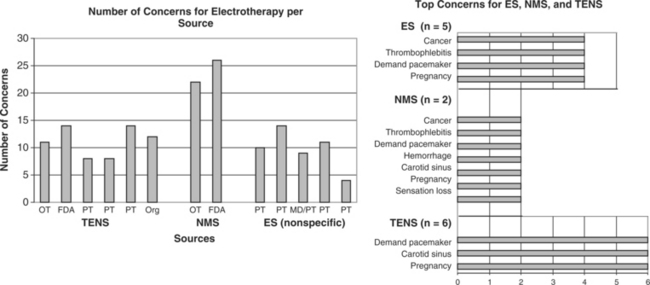

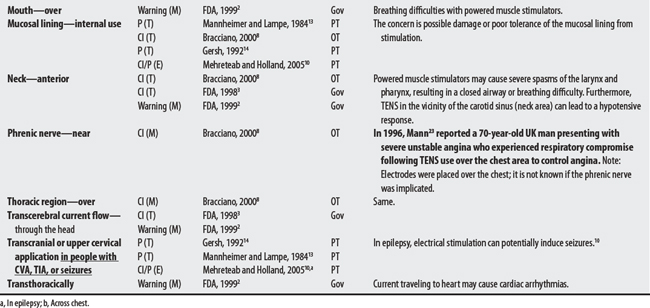

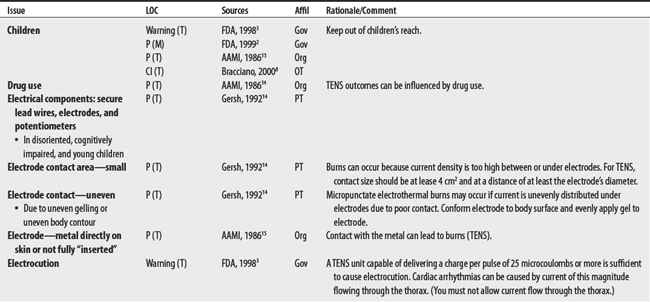

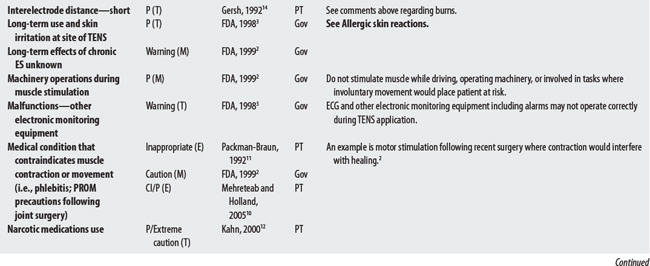

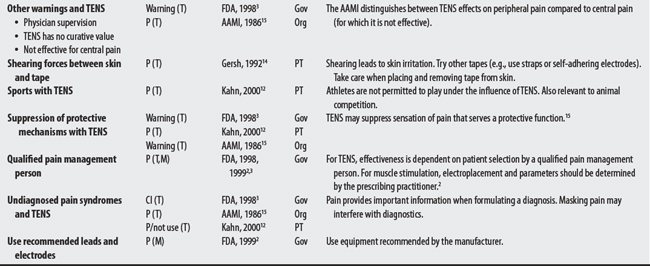

The literature tends to treat electrical stimulation either in general terms, or alternatively, addresses motor (NEMS, or powered muscle stimulator) and pain modulation (TENS) modality concerns separately (as the FDA does).2,3 In this text, I differentiate among NMES, ES, and TENS concerns.

GUIDELINE SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES.

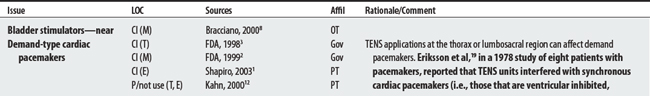

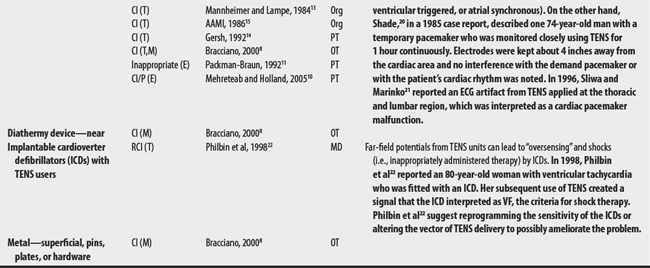

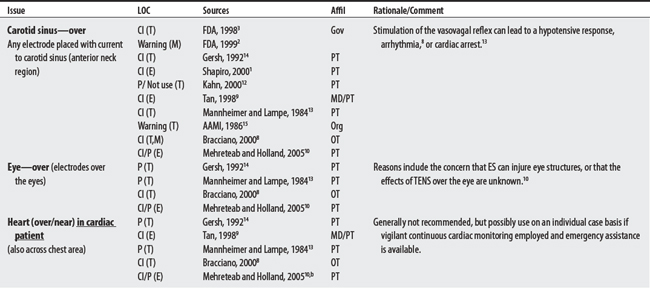

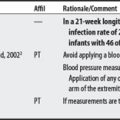

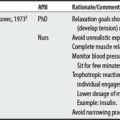

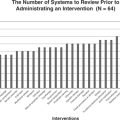

NEMS, ES, and TENS shared some concerns: demand pacemakers, pregnancy, and treatments over the carotid sinus. On the other hand, modality-specific concerns were also apparent in this sample. For example, TENS had distinct concerns for undiagnosed pain, suppression of protective sensory mechanisms, and narcotic/drug use. This would make sense because TENS is used primarily for pain control. Also noteworthy, procedural concerns appear more common during TENS use (17 procedural concerns) than for NEMS (6 procedural concerns). In contrast, NEMS guidelines contain more motion-related concerns such as thrombophlebitis, fractures, hemorrhaging, the operation of machinery (e.g., driving), and conditions where movement is contraindicated. Again, this seems logical, in that NEMS affects muscle contraction.

OTHER ISSUES.

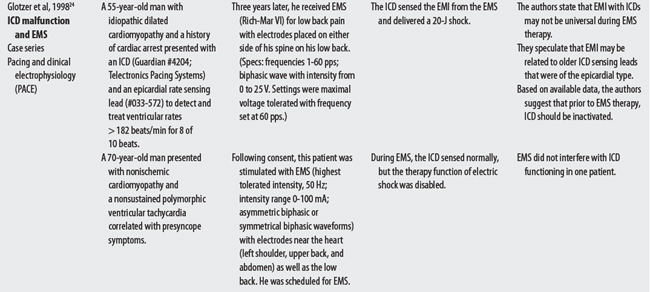

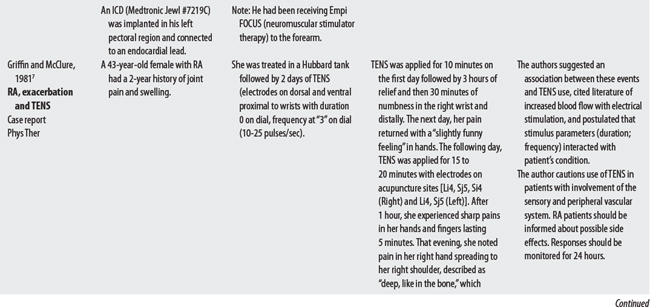

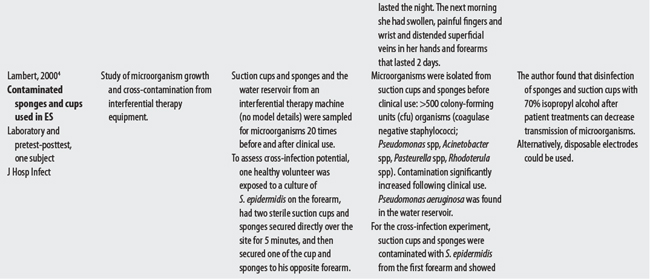

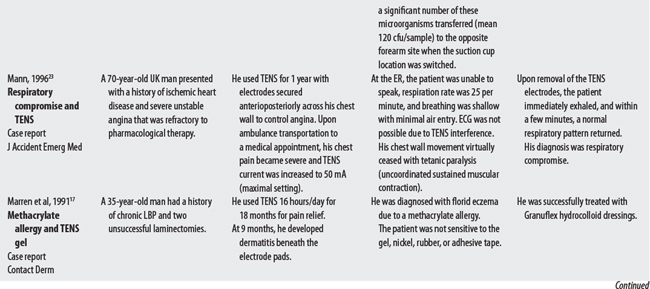

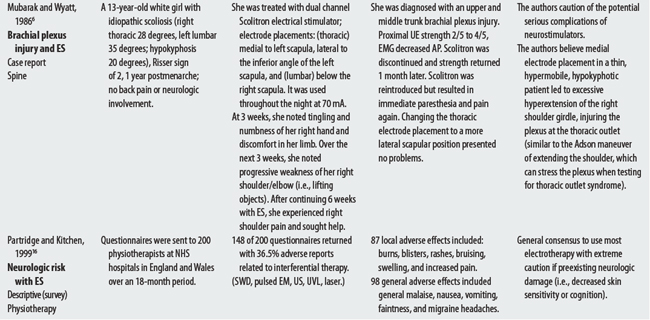

(1) Cross-infection: In a 2000 laboratory-based study, Lambert et al4 sampled microorganisms on suction cups and sponges used during interferential therapy and demonstrated the possibility of cross infection in a healthy volunteer. (2) Partially denervated muscle and direct current: In a 1979 Nature publication, Brown and Holland5 reported that direct current interfered with sprouting in partially denervated muscle. In a critique, one source1 argued that the parameters used in Brown and Holland’s study were unlike those used in patients treated with denervated muscle. (3) Brachial plexus injury: In 1986, Mubarak and Wyatt6 reported a 13-year-old white girl with idiopathic scoliosis who received electrical stimulation to the trunk for scoliosis and subsequently experienced upper/middle brachial plexus injury possibly from stimulus-related shoulder girdle hyperextension near the thoracic outlet. (4) RA: In 1981, Griffin and McClure7 reported a 43-year-old female with RA who experienced a possible circulatory-related exacerbation of her symptoms following TENS use.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS

A00-B99 CERTAIN INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES

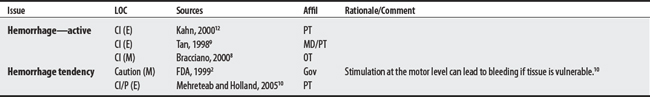

D50-D89 DISEASES OF BLOOD AND BLOOD-FORMING ORGANS AND CERTAIN DISORERS

E00-E90 ENDOCRINE, NUTRITIONAL, AND METABOLIC DISEASES

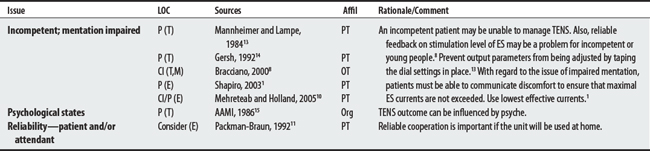

F00-F99 MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

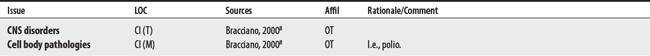

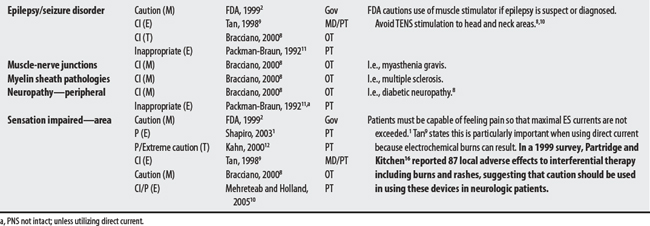

G00-G99 DISEASES OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

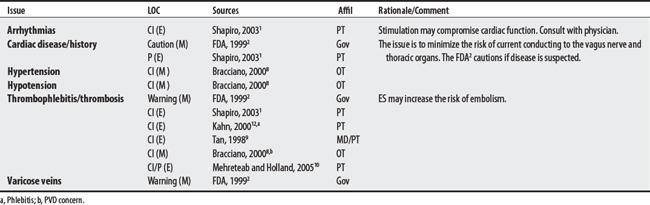

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

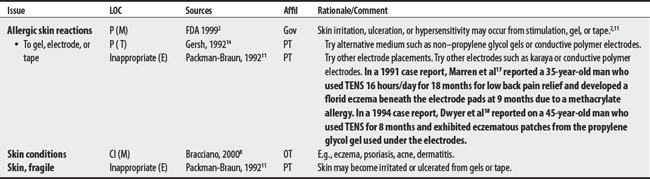

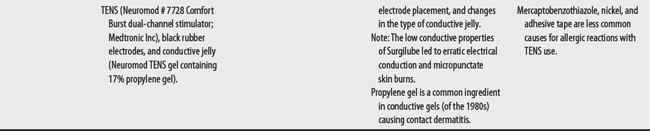

L00-L99 DISEASES OF THE SKIN AND SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUE

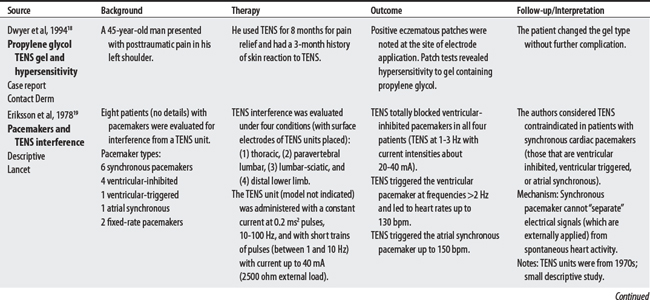

N00-N99 DISEASES OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM

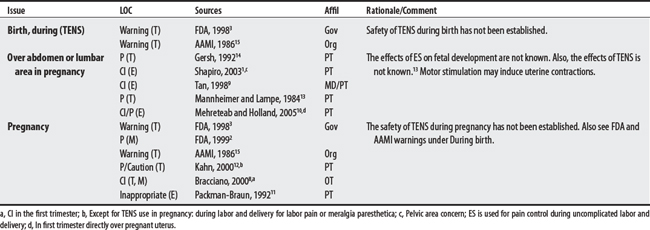

O00-O99 PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND PUERPERIUM

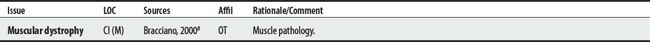

Q00-Q99 CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS, DEFORMITIES, AND CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITIES

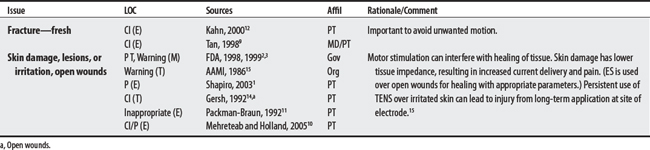

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Shapiro S. Electrical currents. In: Cameron MH, editor. Physical agents in rehabilitation: from research to practice. St. Louis: Saunders; 2003:216-259.

2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance document for powered muscle stimulator 510 (k) s. Center for Device and Radiological Health. http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/mdr/. Accessed November 7, 2005

3 U.S. Department of Health: FDA Guidance for TENS 510(K) Content UD, Department of Health draft August 1994, reformatted October, 29, 1998.

4 Lambert I, Tebbs SE, Hill D, et al. Interferential therapy machines as possible vehicles for cross-infection. J Hosp Infect. 2000;44:59-64.

5 Brown MC, Holland RL. A central role for denervated tissues in causing nerve sprouting. Nature. 1979;282:724-726.

6 Mubarak SJ, Wyatt MP. Brachial plexus palsy resulting from the use of surface electrical stimulation in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1986;11(10):1053-1055.

7 Griffin JW, McClure M. Adverse responses to transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther. 1981;61(3):354-355.

8 Bracciano AG. Physical agent modalities: theory and application for the occupational therapist. Thorofare (NJ): Slack, 2000.

9 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

10 Mehreteab TA, Holland T. Clinical application of electrical stimulation. In: Hecox B, Mehreteab TA, Weisberg J, editors. Integrating physical agents in rehabilitation. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

11 Packman-Braun R. Electrotherapeutic application for the neurologically impaired patient. In: Gersh MR, editor. Electrotherapy in rehabilitation. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1992.

12 Kahn J. Principles and practice of electrotherapy, ed 4. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

13 Mannheimer JS, Lampe GN. Clinical transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1984.

14 Gersh MR. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for management of pain and sensory pathology. In: Gersh MR, editor. Electrotherapy in rehabilitation. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1992.

15 Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation: American national standards for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulators, Biomed WL 26A849ac. 1986 Arlington, VA, 1986, Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

16 Partridge CJ, Kitchen SS. Adverse effects of electrotherapy used by physiotherapists. Physiotherapy. 1999;85:298-303.

17 Marren P, DeBerker D, Powell S. Methacrylate sensitivity and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Contact Dermatitis. 1991;25:190-191.

18 Dwyer CM, Chapman RS, Forsyth A. Allergic contact dermatitis from TENS gel. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;30:305.

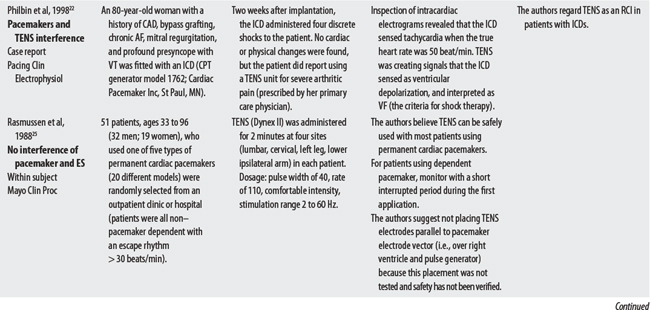

19 Eriksson MA, Schuller J, Sjolund BH. Letter: Hazard from transcutaneous nerve stimulation in patients with pacemakers. Lancet. 1978;1:1319.

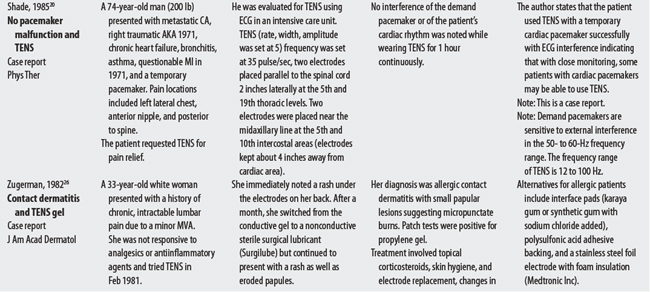

20 Shade SK. Use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for a patient with a cardiac pacemaker: a case report. Phys Ther. 1985;65(2):206-208.

21 Sliwa JA, Marinko MS. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator-induced electrocardiogram artifact: a brief report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;75(4):307-309.

22 Philbin DM, Marieb MA, Aithal KH, et al. Inappropriate shocks delivered by an ICD as a result of sensed potentials from a transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation unit. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:2010-2011.

23 Mann CJ. Respiratory compromise: a rare complication for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for angina pectoris. J Accident Emerg Med. 1996;13:68-69.

24 Glotzer TV, Gordon M, Sparta M, et al. Electromagnetic interference from a muscle stimulation device causing discharge of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: epicardial bipolar and endocardial bipolar sensing circuits are compared. PACE. 1998;21:1996-1998.

25 Rasmussen MJ, Haves DL, Vlietstra RE, et al. Can TENS be safely used in patients with permanent cardiac pacemakers? Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:443.

26 Zugerman C. Dermatitis from transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6(5):936-939.

41.3 Functional Electrical Stimulation

OVERVIEW.

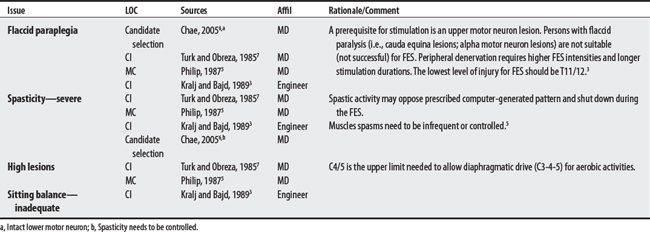

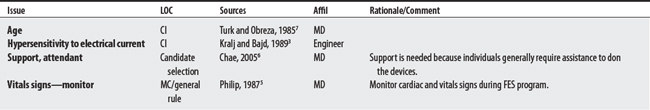

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) is the use of electrical stimulation to activate several muscles in a coordinated sequence for the purpose of achieving a functional goal such as walking or grasping.1 Its concerns in assisting individuals with spinal cord injuries (i.e., paraplegia) to ambulate will be discussed below. Note: In addition to electrostimulation contraindications, specific FES concerns relate to the physiological and physical demands placed on some body systems (e.g., cardiac system, musculoskeletal system) during the act of walking.

SUMMARY: CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS.

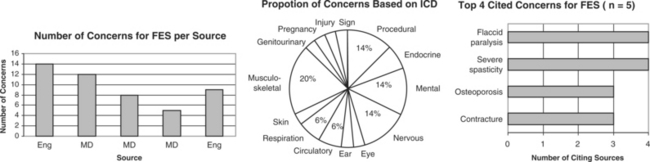

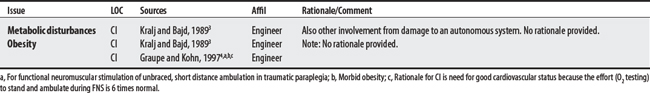

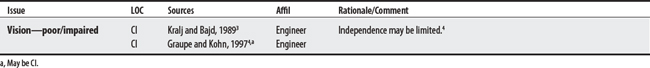

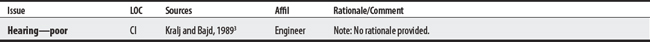

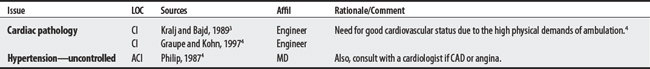

Five sources cited a total of 31 concerns for FES. Concerns ranged from 5 to 14 per source with an engineer citing the largest number. The largest proportion of concerns generally related to musculoskeletal problems (e.g., contractures, osteoporosis). The most frequently cited concerns were the presence of flaccid paralysis or severe spasticity. Uncontrolled hypertension was cited as an absolute CI.

OTHER ISSUES.

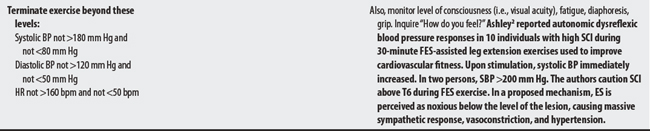

Autonomic dysreflexia has been reported during FES in persons with spinal cord injuries.2

E00-E90 ENDOCRINE, NUTRITIONAL, AND METABOLIC DISEASES

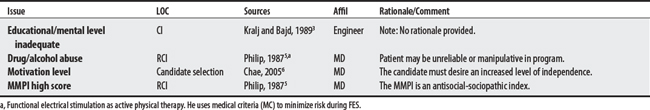

F00-F99 MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

G00-G99 DISEASES OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

H60-H95 DISEASES OF THE EAR AND MASTOID PROCESS

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

J00-J99 DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

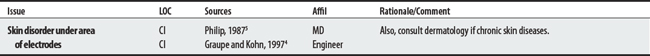

L00-L99 DISEASES OF THE SKIN AND SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUE

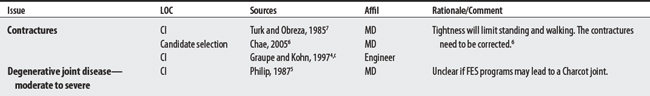

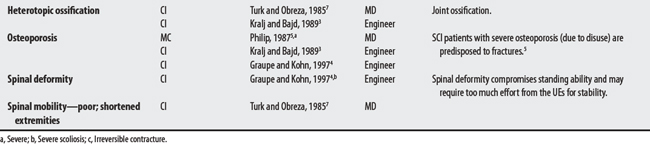

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

N00-N99 DISEASES OF THE GENITOURINARY SYSTEM

O00-O99 PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND PUERPERIUM

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

2 Ashley EA, Laskin JJ, Olenik LM, et al. Evidence of autonomic dysreflexia during functional electrical stimulation in individuals with spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1993;31(9):593-605.

3 Kralj A, Bajd T. Functional electrical stimulation: standing and walking after spinal cord injury. Boca Raton (FL): CRC, 1989.

4 Graupe D, Kohn KH. Transcutaneous functional neuromuscular stimulation of certain traumatic complete thoracic paraplegics for independent short-distance ambulation. Neurol Res. 1997;19(3):323-333.

5 Phillips CA. Medical criteria for active physical therapy: Physician guidelines for patient participation in a program of functional electrical rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med. 1987;66(5):269-286.

6 Chae J, Triolo RS, Kilgore K, et al. Functional neuromuscular stimulation. Delisa JA, editor. Physical medicine and rehabilitation: principles and practices, ed 4, vol 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

7 Turk R, Obreza P. Functional electrical stimulation as an orthotic means for the rehabilitation of paraplegia. Paraplegia. 1985;23(6):344-348.