Chapter 101 Elders in the Wilderness

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

“The elderly still climb mountains: it’s just that their definition of mountains has changed considerably.”16 The Gray Eagles prove the point. This organization consists of elders with a passion who venture regularly into the wilderness.13 They recognize that they are not champions, but enjoy the fellowship, camaraderie, and adventure of wilderness activities. However, altered physiologic function, unrecognized impairments, or the effects of illness and their various treatments can cause serious health issues among elders. Consequently, in the elder population, health problems and untoward medical events associated with outdoor activities can be found more frequently than in younger, more resilient participants. Prevention of such problems is of utmost importance. Intervention may be critical for relief or can even be lifesaving (see Counseling and Teaching Elders Before Wilderness Ventures: The Gray Eagles, later).

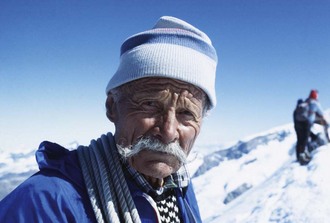

Most extreme performance ventures do not include elders, but there are instances of incredible physical performance from older individuals. Ulrich Inderbinen (Figure 101-1), born in the shadow of the Matterhorn in Zermatt, Switzerland, was a mountain guide who climbed the Matterhorn 370 times, the last time at age 90. He died in 2004 at age 103.47 Keizo Miura (1904-2006), a Japanese ski legend in his own time, became the oldest man to climb Mt Kilimanjaro in 1981, skied down Mont Blanc at age 99, and was a dynamo even beyond his 100th birthday.19

Data regarding elders come from organizations and government services, such as the National Park Service and some local, county, and state emergency medical services, which maintain and report records of wilderness emergencies. The highly respected Explorers Club and the American Alpine Club report on and can advise on health hazards and their preventive measures. Great Old Broads for Wilderness is a vigorous elder women’s group, which, in its own words, “transformed the image of helpless old ladies to one of power and strength as they unite to protect America’s roadless wild lands.”46 Other active organizations, some of which have medical links, can be found on the Internet.

The Aging Process

Aging is a natural consequence of life. It leads to anatomic, biochemical, and physiologic alterations in every organ system (Table 101-1). Common degenerative disorders and diseases include atherosclerotic and cerebrovascular disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; emphysema; diabetes mellitus; arthritis; emotional, mood, and memory disorders (e.g., depression, Alzheimer’s disease); and impaired thermoregulation. Polypharmacy (including excesses in medication intake) is a problem. Accidents due to unsteadiness, falls, forgetfulness, and operating machinery and vehicles take their toll. The cumulative effect of these changes on elders subjected to stressful environments produces a major increase in health risk and health care demand.4,15

The degree of loss of function in various physiologic systems can be approximated by using the “1% rule,” which states that “most organ systems lose function at roughly 1% per year after the age of 30 years.”30 Some age-related biologic changes and their resulting functional changes are listed in Table 101-1.

Etiology of the Aging Process

Some individuals age faster than others. Lifestyle and genetic predisposition are the most commonly incriminated “causes,” but this does not explain the biologic basis for aging.25 Genetic events may somehow determine longevity. For example, there is an increased risk for development of Alzheimer’s disease in the presence of an allele of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene, which encodes a carrier of cholesterol.2 Selman and colleagues have proposed that deletion of ribosomal S6 protein kinase 1 (S6K1) leads to an extended life span and resistance to age-related processes in mice.44 Nevertheless, support for genetic determination of tissue longevity is scant. Most researchers believe that the processes of aging are multifactorial. Speculative theories suggest that damage to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and proteins occurs from a variety of sources, such as reactive oxygen species, including superoxide, the hydroxyl radical, and hydrogen peroxide. According to Hoeijmakers, damage to DNA has implications both for cancer and acceleration of the aging process.26

Hayflick observed that each body cell undergoes a finite number of divisions, roughly 50, after which the cell dies.25 This number of divisions is known as the “Hayflick limit.” Each cell replication has a span of about 18 months and may be a predictor of individual human longevity. For example, with a cellular life span of 18 months, 50 doublings would result in a human life span of 75 years. Variation in the duration of each doubling has been speculated to be a predictor of length of life.

Other theories on the aging process include cellular changes, autoimmune mechanisms, neuroendocrine factors, and even a “biological clock,” but Strehler44 feels that the cause should explain the progressive deleterious and intrinsic changes universal within the species. For example, some animals, usually cold-blooded fish or amphibians, which may grow to an indeterminate size, may also have an indeterminate life span, whereas warm-blooded animals with a limited or fixed size after maturation may die at a more predictable time and at an actuarially determined rate.45

Questions concerning the nature and cause of aging include the following:

Definition of Elders

Classifying Elders by Age and Health

According to the World Health Organization, although there are commonly used definitions of old age, there is no consensus on when a person becomes old.49 Barry and Eathorne3 suggested classifying elders as the hale or the frail. This is a delightful play on words but lacks the precision needed for medical decision making. Smith40 (as reported by Howley) recommends a classification according to chronologic age: (1) athletic old (younger than 55 years), (2) young old (55 to 75 years of age), and (3) old old (older than 75 years of age). However, this classification focuses only on the chronologic age and fails to recognize nonuniform functional change during the passage of years and residual effects of remote illnesses and injuries.

Demography of Elders and the Wilderness

A striking increase in longevity during the 20th century has changed the age composition of Western civilization. Life spans have continued to increase in the 21st century. The median age in the United States in the year 1900 was 23 years. It rose to 30 years in 1950, 33 years in 1990, and 36 years in 2000. More important, the population in the United States older than 65 years has been projected to increase from 35 million (12.4%) in the year 2000 to 71 million (19.6%) in 2030.6 Octogenarians numbered 9.3 million (3.3%) in 2000 and will reach 19.5 million (5.4%) in 2030.

It is not simply the size and growth of this group of seniors that are responsible for its changing medical needs, but rather the nature of the lifestyle and activities adopted by them. Of the 18 million persons between the ages of 65 and 74 years, most are retirees who have stimulated a surge in vigorous outdoor recreational activities. Many are at medical risk. The largest increases in elders leading up to 1990 occurred in regions in the United States most commonly associated with active outdoor lifestyles.11,20 Florida led the way in 1995, when 19% of the population exceeded 65 years of age. A consequent increase in medical needs warrants consideration of the nature of illnesses, injuries, and services unique to the older adult.

Lifestyle is considered important as a major factor in longevity. Leaf reported three locations in the world where individuals not only live to ages beyond 100 years, but are expected to do so.33 These locations are in relatively remote mountainous areas: the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia, the Andes in Ecuador, and the Karakoram range in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. Speculation suggests that this longevity is due to a combination of factors, including genetic selection and a physically active lifestyle.

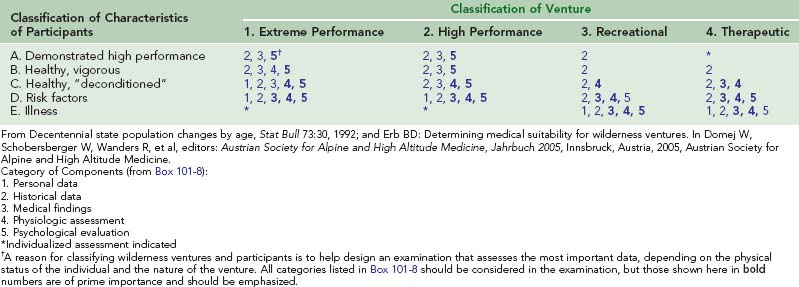

In keeping with these data and exposure to various life events, it is helpful to classify wilderness ventures according to demands required by the activity. A useful classification includes (1) extreme-performance ventures, (2) high-performance ventures, (3) recreational activities, and (4) therapeutic activities (Table 101-2). Mechanics for matching individuals according to their functional classification with the demands of the venture are described in Matching Individuals With Widerness Physical Activities, later.

| Class | General Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extreme-performance ventures |

Why Some Elders Venture Into the Wilderness

The U.S. National Park System studied the frequency of recreational activities in the National Parks from 1982 to 1983 and found, in order of frequency, the following activities: driving for pleasure, sightseeing, walking for pleasure, picnicking, stream/lake/pool swimming, and motor boating.9

A repeat survey, completed by the National Park Service in 1994, found that walking has become the most popular single outdoor activity and now involves over 134 million participants. Walking is especially attractive for an older person because it is healthful, self-paced, and socially rewarding when enjoyed with others. With population increases of persons age 70 and older, predictions indicate that many new trails and walking venues will be needed. The most striking change in activities is the dramatic increase in bird watching, having risen from 21 million in 1982 to 54 million in 1994, an increase of 155%. Growth in participation within other activities includes hiking (94%), backpacking (73%), downhill skiing (59%), and primitive area camping (58%).10

Nash concluded that the personal reasons for elders to venture into the wilderness are for enjoyment of nature, physical fitness, tension reduction, tranquility and solitude away from noise and crowds, experiences with friends, enhancement of skill and competency, and excitement or even the thrill of risk-taking36 (Figure 101-2, online). Some ventures, however, such as off-road motorcycling, kayaking, and cross-country skiing, take place in difficult and inaccessible areas under extraordinary environmental circumstances (cold, altitude, rough terrain). If an emergency occurs in such locations and circumstances, search and rescue services or medical intervention may be required.

Classifying Wilderness Ventures

One classification scheme for wilderness ventures ranges from those that are extremely demanding and risky undertakings to those with minimal physical and environmental requirements (see Table 101-2). Although this classification is very general, it can be helpful in examining prospective participants and matching demands of the wilderness task or activity facing that individual.12,14

Classification of Individuals Considering Wilderness Ventures

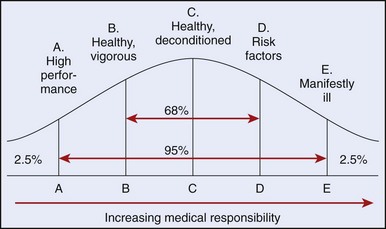

Two basic physiologic factors affect the physical relationship between the venture and the participant: (1) the physical workload of the activity and (2) the capacity of the individual to tolerate the physical workload as influenced by the environmental stressors. Physical demands of the venture were classified previously. A similar classification assists in matching the participant with the venture (Table 101-3). The populations presenting to the physician may fit the distribution curve shown in Figure 101-3, where the groups defined in Table 101-3 are graphed. These classifications serve as starting places for more precise recommendations for the individual presenting to the physician for advice concerning physiologic capacity to tolerate the physical demands of a specific adventure.12,14,15

TABLE 101-3 Classification of Participants in Wilderness Ventures

| Group | General Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| A | Demonstrated high-performance individuals | Athletes in training |

| Mountaineers continually active and in training | ||

| Workers involved with heavy physical tasks | ||

| B | Healthy, vigorous individuals | Athletes |

| Active hunting guides | ||

| C | Healthy deconditioned individuals | Young to middle-aged, healthy business and professional people who are moderately active |

| D | Individuals with risk factors | Individuals at risk because of age, lifestyle, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, or factors not under their control. Most elders are in this group |

| E | Individuals who are manifestly ill | People at any age with chronic illness or physical limitations, such as heart disease, diabetes, or neuromuscular or orthopedic problems |

FIGURE 101-3 Classifying prospective participants according to physical characteristics, functional capacity, and experience helps match the candidate with demands of the venture. Here, prospective participants are arranged with an idealized representation of participants divided by standard deviations according to the classifications in Table 101-3.

Physical Conditioning to Prepare Elders for Wilderness Ventures

Elders considering wilderness activities should consider the appropriateness of their participation in a contemplated venture. After a medical and functional examination, the classification may suggest the need for a physical conditioning program to increase individual reserve capacity. An individual can tolerate an energy cost of approximately one-fourth to one-third of his or her maximal physical work capacity over a period of 8 hours. If the demands of a venture exceed predicted tolerance, PWCmax can be enhanced by 15% or more by a 3- to 6-month graduated conditioning program. A conditioning program should begin with a warm-up session that includes flexion and extension exercises, followed by a cardiovascular conditioning component and a cool-down component. The aerobic component should last at least 20 minutes at a level of about 50% of individual PWCmax. Some persons can learn to monitor the pulse rate corresponding to this level of activity as a monitoring technique. Mouth breathing, which usually occurs at about 60% of maximal work capacity, is also a useful body signal for marking the intensity of the activity. As intensity increases, catecholamines increase. Above 70% of maximal work capacity, the catecholamine level may be hazardous for an individual with subtle cardiovascular disease. Consequently, if the subject keeps the intensity of the activity below that requiring mouth breathing, the aerobic activity should be in the range below 60% of the individual maximal capacity, a relatively safe range in healthy individuals. This level of conditioning is helpful and may be reasonably safe for seniors, although not at the level necessary for conditioning competitive athletes. If cardiovascular disease is present, a conditioning program should be individualized and supervised. A structured program is an ideal time for teaching an individual to read his or her personal body signals, a collection of markers for physiologic responses to activity (Box 101-1).

BOX 101-1 Body Signals

The American College of Sports Medicine has developed a position paper on exercise and physical activity for older adults. This should be reviewed by any serious student of the subject.1 Recommendations include endurance training to help maintain and improve cardiovascular function and strength training to help offset loss of muscle mass. Standards for exercise programs for subjects with cardiovascular disease have been available from the American Heart Association since 1979.17 Additional benefits from regular exercise include improved bone health, reduction of risk from osteoporosis, improved postural stability, and increased flexibility and range of motion. Psychological benefits include a feeling of well-being, relief of symptoms of depression often associated with older adults, and a general joie de vivre.

Environmental Stresses and Elders

Heat

Heat-related illnesses (see Chapters 4, 10, and 11) range from heat edema to life-threatening heat stroke. Tolerance to heat depends on characteristics of the host, including health status, medications, frequency and duration of exposure, history of recent acclimatization, and prevalent environmental factors. Industry has considered levels for permissible exposure limits (PEL), threshold limit values (TLV), and standards for maximal exposure, but there has been no consensus on an exact environmental stress index for heat.

Additional environmental factors, such as high humidity, high winds, and infrared and ultraviolet radiation exposure, may modify levels of an individual’s tolerance to heat, partly through skin changes. It is valuable to teach individuals to be aware of the environment and associated responses such as warmth, coldness, or dampness in the skin. It is also helpful to advise the prospective wilderness venturer that, as a general rule, it takes a breeze of greater than 5 knots (5.75 mph) to be felt on the skin of the face. This is one of a large group of recognizable somatic and sensory observations known as “body signals” (see Box 101-1). Characteristics of elders who are vulnerable to heat exposure are listed in Box 101-2. Actions that may help prevent heat injury are suggested in Box 101-3.

BOX 101-2 Contributors to Heat Exposure Vulnerability in Elders

Cold

Cold exposure (see Boxes 101-4 to 101-6) is poorly tolerated among elders. The complex mechanisms that control body temperatures in elders are not as responsive as in younger people.8 Peripheral vasoconstrictive response to cold is diminished. Systolic hypertension through stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system is exaggerated in a cold environment. Cardiac workload is increased; consequently, in the presence of coronary artery disease, angina is frequently precipitated by exertion and cold. Four avoidance factors for persons with coronary artery disease, the “four E’s of angina,” are exertion, emotion, eating excessively, and exposure to cold.

BOX 101-4 Characteristics of Elders Vulnerable to Cold Exposure

BOX 101-5 Prevention of Cold Injury in Elders

BOX 101-6 Characteristics of Elders Vulnerable to Altitude Illness

Peripheral vasoconstriction, the fundamental mechanism for heat conservation, may be enhanced to some small degree by long-term exposure to cold. When an elder recognizes personal intolerance to cold, he or she may begin a program of gradual increase in exposure to cold. Prevention of cold injury, however, is best achieved through a learning process derived from experience. Elders should never venture unaccompanied into the cold wilderness. Judgment, orientation, and independent responsibility may be impaired in elders who find themselves lost in the cold or in a rescue situation. Characteristics of elders who are vulnerable to hypothermia and cold injury are listed in Box 101-4. Some useful preventive measures are suggested in Box 101-5.

Altitude

The effects of altitude and incidence of altitude illness among elders are not clearly understood in spite of extensive study on altitude among younger, more vigorous subjects. Hackett23 reported that aging reduces physiologic components of the gas exchange process that maintain oxygenation, such as vital capacity and hypoxic ventilatory drive. Older persons are known to have a lower arterial PO2 because of the thickening of the pulmonary alveolar-capillary membrane.31

Houston,28 Honigman,27 and others studied the general population at moderate altitude (2000 to 3000 m [6500 to 9750 feet]) elevation at ski resorts in Colorado. Predictors of mountain sickness included chronic residence at altitude greater than 1000 m (3250 feet) before a high-altitude venture, underlying lung problems, previous history of acute mountain sickness (p <0.05), and surprisingly, age younger than 60 years. This apparent paradox probably is due to natural self-selection among the small group of elderly individuals who are exposed to altitude and activity.

Roach and colleagues studied 97 older men and women (ages 59 to 83 years) over a 5-day period in Vail, Colorado, at a moderate elevation of 2500 meters. They concluded that it was generally safe for older men and women with underlying, asymptomatic cardiovascular and lung disease to make short sojourns to moderate altitudes. In particular, they suggested that hypertension was not a contraindication for travel to moderate altitudes, although blood pressure should be closely monitored and antihypertensive medication continued as prescribed. Of note, their subjects had a short stopover at lower altitude, and the authors acknowledge that selection-bias may have played a role in this particular study.43

Honigman and colleagues27 found that the most frequent predictors of acute mountain sickness are (1) altitude of greater than 1000 m (3250 feet) for residence, (2) history of previous episode of acute mountain sickness, (3) age younger than 60 years, (4) poor or average physical condition, and (5) lung disease. The risk for altitude sickness among elders is increased by poor physical condition, alcohol intake, preexisting pulmonary disease, medication, and excessive activity within the first 12 hours after arriving at altitude. Alcohol tolerance is variable, so total abstinence during a wilderness venture is recommended. It is prudent to avoid sedatives and hypnotics at high altitude.

Acetazolamide, is the drug of choice for prophylaxis against periodic breathing.24 Acute mountain sickness may warrant 125 to 250 mg up to twice a day for treatment. Elders may experience side effects such as weakness, nausea, and paresthesias with large doses, so caution is encouraged. Characteristics of elders who are vulnerable to altitude illness are listed in Box 101-6. Preventive measures are suggested in Box 101-7.

BOX 101-7 Prevention of Altitude Sickness in Elders

Clinical Medicine in Elders

There are two important occasions when wilderness medical leaders should consider health/medical evaluation for older venturers: (1) during the planning phase before the venture and (2) following symptoms that may occur during or after the venture. Components of the pretrip evaluation are based on the characteristics of the individual and on the nature of the proposed venture. These are discussed later (see Medical Examination). Evaluation after the onset of symptoms or for intervention requires clinical judgment dictated by the specific problem or symptom and is considered in discussions of specific illnesses.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular Assessment Prior to Wilderness Venture

A fascinating philosophical discussion dealing with the limitations of wilderness activities in people who have undergone cardiac surgery appeared in a series of letter exchanges and editorials in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The conclusion places the decision-making process squarely on the clinical judgment of the cardiologist on a case-by-case basis.39

Hypertension

Hypertension, the “silent killer,” is an important marker for potential cardiovascular problems. Cardiovascular mortality has been shown to be three times as high in hypertensive elders compared with those who have normal blood pressure. Complications include angina, myocardial infarction, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic), and renal failure. The most widely accepted values of blood pressure considered to represent hypertension are systolic pressure above 140 mm Hg or diastolic over 90 mm Hg. In a health survey in England,37 systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg was observed in 35% of men and 37% of women ages 65 to 74, increasing to 41% and 49%, respectively, after age 75 years. Isolated systolic hypertension is almost exclusively a disorder of elders, with a prevalence of 0.8% at age 50 years, 12.6% at 70 years, and 23.6% at 80 years.43

Mortality rates for systolic hypertension-associated heart failure (10% to 15%) are higher than for diastolic hypertension-associated heart failure (5% to 8%).50 In addition, elevated systolic blood pressure may portend a worse outcome than elevated diastolic blood pressure as a risk factor for heart disease.7 Lewington and colleagues point out that between the ages of 40 and 69 years, each incremental increase in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg (or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg) approximately doubles one’s risk of death from stroke and ischemic heart disease. They note that between the ages of 80 and 89 years, these differences are half as extreme, although the “annual absolute risk is still greater in older age.”34

There is an increased effect of oral sodium intake on blood pressure in elders. An increase of 100 mmol/day is associated with a 10 to 15 mm Hg rise in systolic pressure, compared with a 4 to 5 mm Hg rise in younger adults who ingest the same sodium load.32 In elders, isolated systolic hypertension is recognized as a predictor of stroke.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

The prevalence of certain gastrointestinal disorders is increased among elders. Because a majority of older adults now live in the developed world, associated changes in diet and lifestyle have led to a constellation of common gastrointestinal disorders that Denis Burkitt called afflictions of “modern Western civilization.” These include appendicitis, diverticular disease, colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and gallstones.5,22

Menopause

As ovarian production of estrogen declines, the androgen/estrogen ratio changes dramatically. Gonadotropin feedback results in increased follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in a range of up to 30 MIU/mL. Progesterone secretion is variable and may either increase or decrease.42 Resulting anatomic changes from these hormonal alterations may affect lipid ratios, the coronary arteries, cortical and trabecular bone, and changes in body fat distribution with a shift in fat toward the center of the body. Changes in cognitive functions have also been reported.

Combinations of estrogens and progestins may be used in treatment.30 Examples include:

Transdermal route of administration may be convenient in the wilderness setting.

The Senses

Obesity

Almost two-thirds of adults in the United States are overweight and over 30% are obese, according to National Institutes of Health data collected from 1999 to 2000.48 There is widespread recognition that weight has become a very significant problem affecting morbidity, mortality, health care services, productivity, and economic costs.

Overweight is identified by NIH as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater. The World Health Organization also recommends defining overweight as a BMI of greater than 25.48

Among people with type 2 non–insulin-dependent diabetes, 67% have a BMI greater than 25. Hypertension is found in 22.1% of men with a BMI greater than 25, but is found in only 14.9% of those with a BMI less than 25.48 These figures indicate that weight is a risk factor and a predictor of illness. Life expectancy is shortened 2 to 5 years with moderate obesity. Obese people have a 50% to 100% increase in all-cause risk for premature death.48

Many obese individuals who recognize their problems may begin a weight reduction program that includes not only dietary controls but also exercise activities, especially walking. Energy expenditure while trail walking18 may be calculated from speed of walking and grade of the trail using the following formula:

Caloric expenditure may be calculated from this energy cost. The energy calculated from the above formula may be modified by the physical characteristics of the trail terrain such as soil, asphalt, scree, and snow. Terrain coefficients are available for estimating the increased energy expenditure while traversing difficult terrain.41

Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, and Polypharmacy

Excessive use of medicines is often seen.29 Polypharmacy represents a less-than-desirable state of duplication of medications, failure to recognize potential drug interactions, and inadequate attention to pharmacokinetics and pharmacologic principles.35 Alcohol abuse frequently compounds the problem of polypharmacy. It is a great help to have each participant carry all presently consumed medications to his or her physician for review before the wilderness venture.

Medical Examination

Components of the Medical Examination

A survey of wilderness leaders served as the basis for developing specific components of a medical examination for prospective participants in wilderness activities.12,14,15 The five categories of characteristics included in the health examination are shown in Box 101-8.

BOX 101-8 Components of the Medical Examination

max using a treadmill, cycle, or step ergometry. Functional testing with electrocardiographic monitoring is frequently used for diagnostic testing and for predicting cardiovascular response to exercise. Testing by running for speed or endurance and evaluation of dynamic strength and agility are rarely used but are interesting during skill assessment. Testing for hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) may be primarily of research interest but nonetheless should be considered if precision is needed for elders going to high altitude.

max using a treadmill, cycle, or step ergometry. Functional testing with electrocardiographic monitoring is frequently used for diagnostic testing and for predicting cardiovascular response to exercise. Testing by running for speed or endurance and evaluation of dynamic strength and agility are rarely used but are interesting during skill assessment. Testing for hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) may be primarily of research interest but nonetheless should be considered if precision is needed for elders going to high altitude.The content of a medical examination, consisting of any or all of the five categories listed in Box 101-8, matches the characteristics of the individual with the characteristics of the venture and identifies the components of the medical examination that may be needed (Table 101-4).

Counseling and Teaching Elders Before Wilderness Ventures: The Gray Eagles

The love of the wilderness fuels the spirit that hears the call of the wild. Aging seems only to sharpen this desire and to deepen its significance. One group of aging individuals who answered the song was the Gray Eagles (Figure 101-4, online), the brainchild of Memphis pathologist, Dr. John K. Duckworth and retired food executive, Mr. John C. Johnson.13 After years of recreational hikes, these seasoned outdoorsmen formalized their group in 1989. They invited individuals to participate in wilderness backpacking trips to such places as the Wind River Range in Wyoming, Banff National Park in Canada, the Beartooth Range in Montana, and the Olympic Range in Washington State. Their experiences have been invaluable in providing a unique opportunity to learn about the medical problems of groups in the wilderness.

With a record of over 3500 person-days in the wilderness, this group has sustained very few serious medical problems. Most problems consist of consequences of environmental exposure, trauma, infectious processes, and neuropsychiatric disorders (Box 101-9). Fatigue, minor musculoskeletal problems, and manageable trauma were encountered relatively often. One successful year of participation by an elder person does not necessarily guarantee that the next year will be uneventful. With increasing age causing reduced reserve, an elder’s tolerance to the effort may change dramatically, and subtle symptoms may evolve into a full-blown emergency. Problems confronted by the Gray Eagles with the most serious potential have been behavioral aberrations from organic brain syndrome not previously recognized but precipitated by the environmental and physical stress of the venture.

BOX 101-9 Medical Problems Encountered by the Gray Eagles During 3500 Person-Days in the Wilderness

Environmental Problems

1 American College of Sports Medicine. Position stand: Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:992.

2 Baker AT, Martin GR. Molecular and biological factors in aging: The origins, causes, and prevention of senescence. In Cassel CK, Cohen HJ, Larson EB, et al, editors: Geriatric medicine, ed 3, New York: Springer, 1996.

3 Barry HC, Eathorne SW. Exercise and aging. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78:357.

4 Bowman WD: Problems of older people in the wilderness. Syllabus, Wilderness Medical Society Winter Meeting, February 1997, pp 345-349.

5 Burkitt DP. Some diseases characteristic of modern western civilization. BMJ. 1973;1:274.

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health and aging: Trends in aging—United States and worldwide. MMWR. 2003;52:101.

7 Chobanian AV. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. NEJM. 2007;357:789.

8 Collins KJ, Abdel-Rahman TA, et al. Circadian body temperatures and the effects of a cold stress in elderly and young subjects. Age Ageing. 1995;24:485.

9 Cordell HK, Hartman LA, Watson AE, et al. The background and status of an interagency research effort: The Public Area Recreation Visitors Survey (PARVS). In: Cordell BM, editor. Proceedings, Southeastern Recreational Research Conference, 1986 (2). Asheville, NC; Athens, Ga: Institute of Community and Area Development, University of Georgia; 1987:19-36.

10 Cordell HK, Teasley J, Super G, et al: Outdoor recreation in the United States: Results from National Survey on Recreation and the Environment. USDA Forest Service, 1997.

11 Decentennial state population changes by age. Stat Bull. 1992;73:30.

12 Erb BD. Determining medical suitability for wilderness ventures. In: Domej W, Schobersberger W, Wanders R, et al, editors. Austrian Society for Alpine and High Altitude Medicine, Jahrbuch 2005. Innsbruck, Austria: Austrian Society for Alpine and High Altitude Medicine, 2005.

13 Erb BD. Elderly in the wilderness: The Gray Eagles. Wilderness Med Lett. 1995;1:8.

14 Erb BD: Medical selection of participants in wilderness ventures. In Syllabus, Wilderness Medical Society Annual Meeting, August 1995, pp 489-494.

15 Erb BD. Predictors of success in wilderness ventures: Physical activity, the environment and fatigue. Wilderness Med Lett. 1990;7:8.

16 Erb BD. The elderly in wilderness. Wilderness Med Lett. 1995;12:6.

17 Erb BD, Fletcher J, Sheffield T. Standards for cardiovascular exercise treatment programs. Circulation. 1979;59:1084A.

18 Erb RE. Precision in measuring terrain travel. The Study Center. June 1985.

19 Faiola A. Old, but not retiring. Washington Post. 2004;27:A1. October

20 Geographic profile of the aged. Stat Bull. 1993;4:2.

21 Glenn J. John Glenn Quotes. http://thinkexist.com/quotation/there_is_still_no_cure_for_the_common_birthday/209791.html.

22 Goldacre MJ. Demography of aging and the epidemiology of gastrointestinal disorders in the elderly. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2009;23:793.

23 Hackett P: New concepts of high altitude cerebral edema: Acute mountain sickness. Personal communication, 1987.

24 Hackett PH, et al. Respiratory stimulants and sleep periodic breathing at high altitude: Almitrine versus acetazolomide. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:896.

25 Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961:585.

26 Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging and cancer. NEJM. 2009;361:1475.

27 Honigman B, Theis MK, Kozial-McLain J, et al. Acute mountain sickness in a general tourist population at moderate altitudes. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:587.

28 Houston CS. Incidence of acute mountain sickness: A study of winter visitors to six Colorado resorts. Am Alpine J. 1985;27:162.

29 Jones BA. Decreasing polypharmacy in clients most at risk. AACN Clin Issues. 1997;8:627.

30 Kaiser FE, Wilson M-MG, Morley JE. Menopause/female sexual function. In Cassel CK, Cohen HJ, Larsen EB, et al, editors: Geriatric medicine, ed 3, New York: Springer, 1996.

31 Kronenberg RS, Drage CW. Attenuation of the ventilatory and heart rate responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia with aging in normal men. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1812.

32 Law WR, Frost CD, Weld NJ. By how much does dietary salt reduction lower blood pressure? I. Analysis of observational data among populations. Br Med J. 1991;312:811.

33 Leaf A. Every day is a gift when you are over 100. Natl Geogr. 1973;143:93.

34 Lewington S, Clarke R, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903.

35 Monane M, Monane S, Semia T. Optimal medication use in elders: Key to successful aging. West J Med. 1997;167:233.

36 Nash R. Wilderness and the American mind, ed 3. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 1982.

37 Office of Public Sector Information Social Survey Division. Health Survey for England, 1993. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1994.

38 Perspectives. Newsweek, June 21, 1999.

39 Rennie D. Will mountain trekkers have heart attacks? JAMA. 1989;261:1045.

40 Smith EL. Special considerations in developing exercise programs for the older adult. (reported by Howley EH)]. Matarazzo JD, editor. Behavioral health: A handbook of environmental enhancement and disease prevention. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1984.

41 Soule R, Goldman R. Terrain coefficients for energy cost prediction. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:706.

42 Speroff L. Menopause and hormone replacement therapy. Clin Geriatr Med. 1993;9:33.

43 Straessen J, Amery A, Fagard R. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. J Hypertens. 1990;8:393.

44 Strehler BL. Concepts and theories in aging. In: Viidik, editor. Lectures on gerontology. New York: Academic Press; 1982:1-57.

45 Thompson DW. On growth and form, ed 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1942.

46 Trail and Timberline. Great Old Broads for Wilderness. http://www.cmc.org/cmc/tnt/..

47 Ulrich Inderbinen, the world’s oldest mountain guide [obituary]. The Economist. 86, 2004.

48 Weight-Control Information Network, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Statistics related to overweight and obesity. http://www.clevelandclinic.org/health/health-info/docs/1000/1058.asp?index=5783&src=newsp.

49 World Health Organization. Definition of an older or elderly person. Health Statistics and Health Information System. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/index.html.

50 Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part 1. Circulation. 2002;105:1387.

, calories (1000 cal = 1 Kcal or 1 C [Cal]) or as metabolic equivalents (METs).

, calories (1000 cal = 1 Kcal or 1 C [Cal]) or as metabolic equivalents (METs). max) decreases 5% to 15% per decade after age 25 years. β-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers may also influence cardiac output by modifying heart rate and myocardial contractility.

max) decreases 5% to 15% per decade after age 25 years. β-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers may also influence cardiac output by modifying heart rate and myocardial contractility. max. Experience teaches us that a degree of adaptation results from frequent and extended periods of exposure.

max. Experience teaches us that a degree of adaptation results from frequent and extended periods of exposure.