Chapter 223 Ehrlichioses and Anaplasmosis

Etiology

Although these infections are caused by bacteria assigned to various genera, the name ehrlichiosis has been applied to all. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) is used to describe disease characterized by infection of predominantly monocytes caused by E. chaffeensis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) to describe disease of circulating neutrophils caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and ewingii ehrlichiosis caused by E. ewingii (see Table 220-1).

Transmission

The predominant tick species that harbors E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii is Amblyomma americanum, the Lone Star tick. Additional vectors such as Dermacentor variabilis, the American dog tick, have not been proved but might explain the presence of HME outside the known range of A. americanum (see Fig. 220-1). The tick vectors of A. phagocytophilum are Ixodes, including I. scapularis (black-legged or deer tick) in the eastern USA (Fig. 220-1), I. pacificus (western black-legged tick) in the western USA, I. ricinus (sheep tick) in Europe, and I. persulcatus in Eurasia. Ixodes species ticks also transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, Babesia microti, and, in Europe, tick-borne encephalitis-associated flaviviruses. Co-infections with these agents and A. phagocytophilum have been documented in children and adults.

Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species are maintained in nature predominantly by horizontal transmission (tick to mammal to tick), because the organisms are not transmitted to the progeny of infected adult female ticks (transovarial transmission). The major reservoir host for E. chaffeensis is the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which is found abundantly in many parts of the USA. A reservoir for A. phagocytophilum in the eastern USA appears to be the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus. Deer or domestic ruminants may also have persistent asymptomatic infections, but the genetic variants in these reservoirs might not be infectious for humans. Efficient transmission requires persistent infections of mammals, long recognized in dogs with Ehrlichia canis, ruminants with A. phagocytophilum, and other hosts of various ehrlichial species. Although E. chaffeensis and A. phagocytophilum can cause persistent infections in animals, documentation of chronic infections in humans is exceedingly rare. Transmission of Ehrlichia can occur within hours of tick attachment, in contrast to the 1-2 days of attachment required for transmission of B. burgdorferi to occur. Transmission of A. phagocytophilum is via the bite of the small nymphal stage of Ixodes spp., including I. scapularis (see Fig. 220-1), which is very active during late spring and early summer in the eastern USA.

Diagnosis

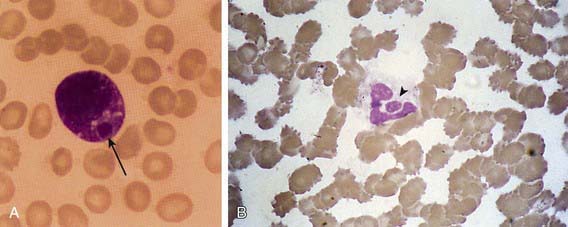

The 1st patient and several subsequent pediatric patients with E. chaffeensis infection were identified presumptively on the basis of typical Ehrlichia morulae in peripheral blood leukocytes (Fig. 223-1A). This finding has been too infrequent to be considered a useful diagnostic tool. In contrast, HGA presents with a small but significant percentage (1-40%) of circulating neutrophils (Fig. 223-1B) containing typical morulae in 20-60% of patients. The distinction between the 2 infections relies on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of species-specific DNA sequences or on the demonstration of specific antibodies to E. chaffeensis or A. phagocytophilum with low titer or absent antibodies to the other agent.

Arnez M, Luznik-Bufon T, Avsic-Zupanc T, et al. Causes of febrile illnesses after a tick bite in Slovenian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1078-1083.

Berry DS, Miller RS, Hooke JA, et al. Ehrlichial meningitis with cerebrospinal fluid morulae. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:552-555.

Buller RS, Arens M, Hmiel SP, et al. Ehrlichia ewingii, a newly recognized agent of human ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:148-155.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis—Maine, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;58:1033-1036.

Dumler JS, Dey C, Meier F, et al. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis: a potentially severe disease in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:847-849.

Hamburg BJ, Storch GA, Micek ST, et al. The importance of early treatment with doxycycline in human ehrlichiosis. Medicine. 2008;87:53-60.

Horowitz HW, Kilchevsky E, Haber S, et al. Perinatal transmission of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:375-378.

Jacobs RF. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis: similar to Rocky Mountain spotted fever but different. Pediatr Ann. 2002;31:180-184.

Jacobs RF, Schutze GE. Ehrlichiosis in children. J Pediatr. 1997;131:184-192.

Krause PJ, Corrow CL, Bakken JS. Successful treatment of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in children using rifampin. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e252-e253.

Lantos P, Krause PJ. Ehrlichiosis in children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2002;13:249-256.

Marshall GS, Jacobs RF, Schutze GE, et al. Ehrlichia chaffeensis seroprevalence among children in the southeast and south-central regions of the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:166-170.

Moss WJ, Dumler JS. Simultaneous infection with Borrelia burgdorferi and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:91-92.

Olano JP, Walker DH. Human ehrlichiosis. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:375-392.

Peters TR, Edwards KM, Standaert SM. Severe ehrlichiosis in an adolescent taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:170-172.

Schutze GE. Ehrlichiosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:71-72.

Schutze GE, Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, et al. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:475-479.

Stone JH, Dierberg K, Aram G, et al. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 2004;292:2263-2270.

Zhang L, Shan A, Mathew B, et al. Rickettsial seroepidemiology among farm workers, Tianjin, People’s Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:938-940.