Chapter 14 Eczema, psoriasis, skin cancers and other skin disorder

Introduction

The integument (the skin) is the largest and heaviest organ in the human body consisting of approximately 16% of body weight and is the primary interface between the internal environment and the outside surroundings.1 Given that the thickness of skin has an extremely thin foundation, the epidermis protects animals against major environmental stresses, such as water loss and microorganism infection. Hence, the skin’s primary function is to act as a barrier to protect the body from damage caused by outside forces, contaminants, microorganisms and radiation exposure.

The skin epidermis and its appendages undergo ongoing renewal by a process called homeostasis. Stem cells in the epidermis have a crucial role in maintaining tissue homeostasis by providing replacement cells to those that are constantly lost during tissue turnover or following traumatic injury. A number of different skin stem cell pools contribute to the maintenance and repair of the various epidermal tissues of the skin. These include the inter-follicular epidermis, hair follicles and sebaceous glands. It is interesting to note that the basic mechanisms and signalling pathways that orchestrate epithelial morphogenesis in the skin are reused during adult life to regulate skin homeostasis.2

In clinical practice, dermatology includes about 3000 diseases that affect the skin and its accessory tissues (e.g. hair and nails).3 While many infamous epidemics with prominent skin manifestations such as small pox, plague, leprosy, and anthrax, have been largely controlled,4 other dermatologic diseases such as warts, acne, and dermatitis remain especially common.

In 2004, more than 50% (165 million) of the US population suffered from herpes simplex virus (HSV) and herpes zoster virus (HZV) infections, and 83.3 million cases of human papilloma virus (HPV) infection were noted.2 Indeed, at any given time, it has been reported that at least 25% of the population of the US suffer from at least 1 skin disease5,6 — a state that constitutes a significant global burden of disease.2, 7–10 A recent study from the US on the burden of skin diseases demonstrated that skin disease was 1 of the top 15 groups of medical conditions for which prevalence and health care spending increased the most between 1987 and 2000, with approximately 1 in 3 persons diagnosed with a skin disease at any given time (see Table 14.1).

| Skin disease | Prevalence in millions as at 2004 |

|---|---|

| Acne (cystic and vulgaris) | 50.2 |

| Actinic keratosis | 39.5 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 15.2 |

| Benign neoplasms/keloid | 29.4 |

| Bullous diseases | 0.14 |

| Contact dermatitis | 72.3 |

| Cutaneous fungal infections | 29.4 |

| Cutaneous lymphoma | 0.02 |

| Drug eruptions | 2.6 |

| Hair and nail disorders | 70.5 |

| Herpes simplex and zoster | 165.0 |

| Human papillomavirus/warts | 58.5 |

| Lupus erythematosus | 0.36 |

| Psoriasis | 3.1 |

| Rosacea | 14.7 |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 5.9 |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 83.8 |

| Skin cancer— melanoma | 0.72 |

| Skin cancer— non-melanocytic | 1.2 |

| Skin ulcers and wounds | 4.8 |

| Solar-radiation damage | 123.1 |

| Vitiligo | 1.5 |

(Source: adapted and modified from Bickers et al. 2006)11

Exposure of the skin to UV light has the potential to induce the formation of high concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can destabilise ROS signalling functions and damage organelles and modify the structures of important molecules such as proteins, lipids and genetic material.12 Sunlight, particularly ultraviolet B (UVB) (wavelength 290–320 nm), is responsible for sunburn, but also causes cellular damage. UVA light (wavelength 320–400 nm) burns less than UVB (wavelength 290–320 nm) and penetrates deep into the dermis (as far as the boundary with the epidermis). UVA light makes up the majority of sunlight, and is absorbed by a wide range of molecules, which can become photosensitisers, and can do more damage to the skin due to its greater ability to penetrate. Environmental pollutants such as ozone and oxides of nitrogen and sulphur are also able to produce free radicals in the skin, thereby also risking skin damage.13 Although formed in the outer layers of the epidermis, these radicals induce damage in deeper layers in a manner similar to UV light.

A number of nutraceuticals have been claimed to exhibit useful activities in the area of skin health, including proanthocyanidins and the pine bark extract Pycnogenol, carotenoids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), tea, soy, glucosamine and melatonin.14

Lifestyle factors

Smoking

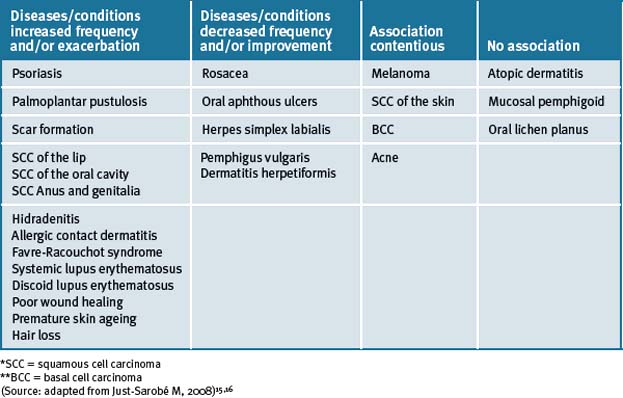

The adverse health risks associated with smoking are well documented and this is also important for overall skin health. Smoking has been associated with the positive and negative prevalence of numerous diseases and conditions of the skin (see Table 14.2).15, 16

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that tobacco smoking is one of many factors that significantly contributes to premature skin ageing in addition to other factors such as age, sex, skin pigmentation, sun exposure history, and alcohol consumption.17–20 Moreover, smoking is the causal factor of smoker’s wrinkles. Similarly, as with chronic exposure of the skin to ultraviolet radiation, tobacco also promotes manifested alterations in the structure and composition of the epidermis and dermis, similarly to that observed with photo-ageing. 21, 22, 23 In a recent study, tobacco smoking, but not ultraviolet exposure, was determined to be a strong predictor of skin ageing.24

Although smoking may have certain beneficial effects on some skin diseases (as described in Table 14.2), it is exceptionally difficult to favour this habit which is highly damaging to overall health. Tobacco smoking is currently the leading preventable cause of disease and death in Western countries, and some of its beneficial effects on the skin are significantly dwarfed when compared to the hazard risks to health encountered with habitual tobacco use for both smokers and those who are exposed to secondary tobacco smoke, therefore it cannot be recommended.

Alcohol

The long-term consumption of alcohol in excessive quantities can damage every organ system in the body. A recent report has documented that chronic excessive alcohol consumption in alcoholics was associated with a wide range of skin disorders that included urticaria, porphyria cutanea tarda, flushing, cutaneous stigmata of cirrhosis, psoriasis, pruritus, seborrheic dermatitis and rosacea.25

Life stressors

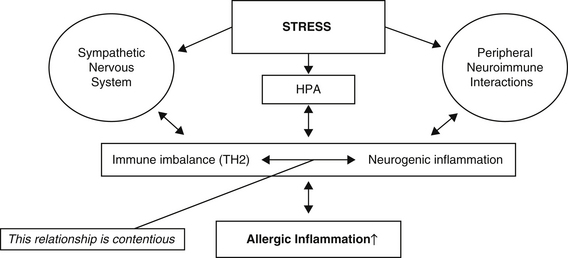

Psycho-emotional stressors have long been expected to exacerbate or even trigger allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis (see Figure 14.1).26, 27

Psychodermatological or psychocutaneous disorders are conditions resulting from the interaction between the mind and the skin. There are 3 major groups of psychodermatological disorders recognised; psychophysiologic disorders, psychiatric disorders with dermatologic symptoms, and dermatologic disorders with psychiatric symptoms.28

A number of human studies have reported associations between personality traits and psychic disturbances such as stress perception, anxiety, or depression and atopic dermatitis severity or even onset.29–32

The nature of the mechanisms that link stress and exacerbation of skin inflammation remain largely unknown. Recent studies suggest psycho–neuro–immunologic factors and emotional stressors are important in its evolution (Figure 14.1).33

The established explanation is that immune balance is altered by activation of 2 stress axes; namely, activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis that raises cortisol levels, and activation of the sympathetic nervous systems which raises adrenaline levels (Figure 14.1).34 This mechanism of activity has been further investigated in wound-healing experiments. For more than a decade it has been extant that stress/stressors (which can range in magnitude and duration) can significantly slow wound healing.35, 36

Itch is a major feature of many skin diseases, which adversely affects patient’s quality of life. Recently it was shown that cognitive factors, such as helplessness and worrying, and the behavioural response of scratching were indicated as possible worsening factors. This is consistent with overall findings that implicate a biopsychosocial model for the itch sensation.37

Sunlight/ultraviolet (UV) exposure

Acute adverse effects of sun exposure

Acute overexposure to sunlight causes sunburn, primarily because of ultraviolet B (UVB) (290–320 nm) radiation. This is characterised by erythema, oedema, and tenderness. Sunburn represents injury to both epidermal and dermal layers.38

Lentigo maligna

Repeated acute exposure over time may enhance the risk of skin disease as reported in a recent epidemiological study. The study reported that although chronically sun-exposed skin was recognised as a prerequisite for lentigo maligna, the risk of lentigo maligna did not increase with the cumulative dose of sun exposure; however, that lentigo maligna was associated with sunburn history, like all other types of melanomas. The main epidemiological characteristic of lentigo maligna reported in this study was the absence of an apparent relation with the genetic propensity to develop nevi.39

Skin cancers

The influence of painful sunburns and lifetime sun exposure to the skin has also been studied in other skin diseases.40 Lifetime sun exposure was predominantly associated with an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and actinic keratoses and to a lesser degree with basal cell carcinoma (BCC). By contrast, lifetime sun exposure appeared to be associated with a lower risk of malignant melanoma, despite the fact that lifetime sun exposure did not diminish the number of melanocytic nevi or atypical nevi. Neither painful sunburns nor lifetime sun exposure were associated with an increased risk of seborrheic warts.

Chronic adverse effects of sun exposure

Carcinogenesis

Over 100 years ago, Paul Gerson Unna correctly identified chronic solar exposure as the cause of SCC.41 The vast majority of the non-melanoma forms of skin cancer (SCC and BCC) result from chronic or intense intermittent solar exposure, and perhaps two-thirds of melanoma worldwide have solar UV radiation (UVR) as an aetiological causal factor.42

The 3 types of skin cancer are: basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); and melanoma.43 (See also Chapter 9.)

Photo-ageing

Photo-ageing is a multisystem degenerative process that involves the skin and its support system. Photo-ageing results from repeated sun exposure rather than to those changes resulting from the passage of time alone.44

Avoiding over-exposure of the skin to the sun can beneficially promote smooth, unblemished skin even in the ninth decade of life, showing only laxity and deepening of the expression lines. Photo-aged skin displays a telangiectatic, leathery, dry, coarse, nodular yellowish surface, with deep wrinkles, accentuated skin furrows, mottled pigmentation, and purpura, as well as a variety of benign, premalignant, and malignant neoplasms. Lifetime sun exposure is also positively associated with xerosis, spider angioma, and superficial varicose veins.45

Contact allergy and the skin

Contact allergy caused by ingredients in cosmetic products is a well-known problem (see Table 14.3). In the US it has been reported that approximately 6% of the general population has a cosmetic-related contact allergy, mainly caused by constituent compounds such as preservatives or fragrances in the cosmetic product.46–49

Table 14.3 Important allergens for consideration in cosmetics

| Allergen | Function |

|---|---|

| Amerchol™ L101 | Emulsifier |

| p-Aminobenzoic acid | Sunscreens |

| Balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae) | Fragrance |

| Benzophenone 3 | Sunscreens |

| 2–Bromo–2–nitropropane–1,3–diol (Bronopol) | Preservative |

| Butylated hydroxyanisole | Antioxidant |

| Butylated hydroxytoluene | Antioxidant |

| Cetyl/stearyl alcohol | Emulsifier |

| Cocamidopropyl betaine | Surfactant |

| DMDM hydantoin |

(Source: data adapted and modified from Ortis, Yiannias49 and Orton, Wilkinson)50

Mind–body medicine

The endocrine system serves as a central gateway for psychologic influences on health. Stress and depression can cause the release of pituitary and adrenal hormones that have multiple effects on immune function that can subsequently influence skin physiology. Furthermore, skin problems associated with depression and or anxiety can be classified accurately as psychophysiologic disorders. They can be elicited and worsened by psychologic factors and, in turn, living with them can be associated with a higher prevalence of emotional disorders, such as depression and anxiety.51 Hence, there is a brain–skin connection via psychoneuroimmunological–endocrine mechanisms that, through human behaviours, can strongly influence the initiation and exacerbation of skin disorders.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

It has been reported that CBTs deal with dysfunctional thought patterns (cognitive) or actions (behavioural) that can damage the skin or can interfere with dermatologic therapies.52 CBT-responsive skin disorders include:

The mechanism by which hypnosis produces improvement in symptoms and in skin lesions is not completely understood. Hypnosis may help regulate blood flow and other autonomic functions not usually under conscious control. The relaxation response that accompanies hypnosis may alter neurohormonal systems that in turn regulate many body functions.53

Biofeedback

Instrumentation that can measure galvanic skin resistance, skin temperature, or other manifestations of autonomic nervous system activity in the skin and then display it in a visual, auditory, or kinesthetic mode gives the individual sensory biofeedback. With training, individuals may learn consciously how to alter autonomic nervous system associated responses for skin problems, and with enough repetition may establish new habit patterns.56

Early reports show that biofeedback of galvanic skin resistance for hyperhidrosis and biofeedback of skin temperature for dyshidrosis and Raynaud’s syndrome can be effective.57, 58 When biofeedback was combined with hypnosis the efficacy was reported to be enhanced.

Psychological/educational interventions

Atopic eczema

Psychological and educational interventions have been incorporated as adjuncts to conventional therapies for children with atopic eczema. These interventions enhance the effectiveness of topical therapy. A recent systematic review has reported that there is a lack of rigorously designed trials (that excluded a recent German study) that provided only a limited amount of evidence of the effectiveness of psychological and educational interventions in assisting to manage atopic eczema in children.59

There is low-level evidence for the use of affirmations, prayer and meditation in ameliorating skin disorders and further studies are required because it has been long recognised that there is a significant link between stress and the development of skin disorders.60

Physical activity

Furthermore, there are numerous studies that have investigated the beneficial effects of physical activity, tai chi and yoga for the management of stress61–65 and it is biologically plausible to conclude that providing advice to patients about the benefits of physical activity, tai chi and yoga may also be favourable options for the management of stress that could indirectly also assist with skin conditions.

Nutrition and the skin

Treatment regimens have their origins from numerous areas that are diversely derived from complementary medicine techniques, historical use and traditional healing systems such as Ayurveda, and the systems fashioned by various empirical nutritional therapists.66

As is well known, diet has been recognised to be important in the treatment of several disorders. For example, stimulants and hot foods have been related to acne rosacea,67 wheat gluten to dermatitis herpetiformis,68 and zinc deficiency to acrodermatitis enteropathica.69 Other nutritional deficiencies have historically been recognised to play a role in dermatitis, such as in vitamin B1 deficiency that leads to pellagra.70

Food sensitivities

Population-based assessments of food allergy are scarce.71 Despite the difficulties in obtaining firm population-based data on the prevalence of food allergies, there has been evidence for a general increase in food allergies, documented best for peanut, sesame, and kiwi, that could be attributed to environmental and dietary factors including reduced immune stimulation from infection; that is, the hygiene hypothesis. There have been changes in the components of the diet, including antioxidants, fats, and nutrients such as vitamin D, as well as the use of medications.72, 73, 74

Addressing food allergies (food sensitivities), is an important nutritional elimination procedure. These are reactions to foods that are far broader than the classical reactions such as urticaria, itchy eyes, and rhinitis. They include any inflammatory manifestation as well as a variety of neurological and other non-inflammatory conditions.75

Food hypersensitivity can be the first stage in the development of allergic diseases, such as atopic eczema.76 It has been reported that clinicians have found that elimination of specific foods found by food challenge to elicit symptoms can lead to significant improvement in eczematous symptoms.77 There is a vast amount of scientific literature claiming that dietary elimination causes improvement of atopic eczema in some cases. However, a recent systematic review portrays the evidence available as weak and the issue of exclusion diets in atopic eczema remains contentious.78

Diets

The eradication from the diet of chemicals is an effective way to eliminate potential skin diseases that are aggravated by chemicals. The Palaeolithic diet has addressed such issues in the scientific/medical literature.79 The essential of this diet involves the consumption of those foods that have a low glycemic index (GI) and consists of meat, fish, vegetable, fruit, roots, and nut consumption and excludes grains, legumes, dairy products, salt, refined sugar, and processed oils. Adherence to this diet in turn minimises the consumption of pesticides, petroleum-based fertilisers, preservatives, artificial flavourings, and artificial food colours.

Acne vulgaris

Studies have reported that excessive intake of refined carbohydrates might contribute to the high rates of acne seen in Western countries through a mechanism involving insulin-stimulated androgen production and that hence nutrition-related lifestyle factors play a role in the pathogenesis of acne and that adhering to a diet with low GI foods improves skin health.80, 81, 82 A recent Cochrane review has reported that improving lifestyle eating profiles such as adhering to a low-GI dietary regimen can improve health outcomes,83 which could in turn improve skin health. The systematic review reported that overweight or obese people on a low-GI diet lost more weight and had more improvement in lipid profiles than those receiving carbohydrate diets. Body mass, total fat mass, body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol all decreased significantly more in the low GI group. In studies that compared ad libitum low-GI diets to conventional restricted energy low-fat diets, participants fared as well or better on the low-GI diet, even though they could eat as much as desired. Therefore, this review concluded that lowering the glycaemic load of the diet appears to be an effective method of promoting weight loss and improving lipid profiles and can be simply incorporated into a person’s everyday lifestyle. This improvement may well extend to include better skin health. A recent study further emphasises that there could be a possible role of desaturase enzymes in sebaceous lipogenesis and the clinical manifestation of acne.84

Nutritional supplements

Beneficial effects have been demonstrated in various experimental model systems including topical application of these ingredients. Recently, oral supplements containing various dietary bioactive molecules have also been reported to be beneficial for skin.87

Vitamins

Vitamin A and analogues

Vitamin A includes all naturally occurring, nutritionally active forms of vitamin A (i.e. retinol, retinyl esters) and the carotenoids. Retinoids include natural metabolic products and synthetic analogues of vitamin A. Vitamin A is physiologically essential for the reproductive system, bone formation, vision, and epithelial tissues. Cutaneous signs of its deficiency include xerosis and phrynoderma. Beta-carotene is a precursor to vitamin A, and is a putative antioxidant, that can protect cell membranes from lipid peroxidation and plants from UV light-induced damage. Retinoids have long historical therapeutic uses since the first introduction of topical tretinoin (retinoid) for the treatment of acne vulgaris.88 An early study demonstrated that orally administered vitamin A to benefit acne when used in high doses (300,000 units per day for women, 400,000 to 500,000 units daily for men) with adverse events reported limited to xerosis and cheilitis.89

There have been approximately 2500 new retinoid compounds synthesized.90 Vitamin A stimulates various aspects of wound repair. It affects fibroplasia, collagen synthesis, epithelialisation, and angiogenesis and is involved in inflammatory processes with specific effects on macrophages, which play a dominant role in wound healing.91

Retinoids already approved for the treatment of dermatological conditions include:

The treatment of disorders of abnormal keratinisation, such as Darier’s disease and Kyrle’s disease, has been ascribed to etretinate and acitretin which are established in Europe for the treatment of Darier’s disease and ichthyosis, especially the nonbullous congenital type.92 In the US, however, these compounds have only been approved by the FDA for psoriasis. Palmoplantar keratoderma also responds well to these drugs, but treatment is justified only in severe cases.93 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has been treated successfully with isotretinoin in the past,94 but now acitretin seems to be the drug of choice in Europe.

It has been reported that retinoids possess certain properties that make them good candidates for cancer prevention and therapy. They are metabolically active compounds that can induce changes in cellular function and appearance, and that can modify the expression of a variety of genes involved in cell growth and differentiation.95

Topical tretinoin, at concentrations of 0.05% and 0.1%, have been used in combination with hydroquinone and corticosteroids for the treatment of melasma.96 Isotretinoin, etretinate, and acitretin have all been used in recalcitrant cases of lichen planus and cutaneous lupus erythematosus with good results.97 Erythropoietic protoporphyria responds to treatment with beta-carotene.

The use of retinoids has been significantly more successful in skin cancer prevention in high-risk patients. Treatment of patients suffering from xeroderma pigmentosum with 2mg/kg/day isotretinoin for 2 years resulted in an average reduction of 63% in the number of skin cancers compared with the 2-year interval before intervention.98

Furthermore, patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC) syndrome have been reported to benefit from the same dose of isotretinoin treatment, as there was a rapid decrease in the number of new BCCs.99 Also transplant recipients are also a high-risk group for the development of skin cancer. It has been reported that etretinate at a dose of 50mg/day and acitretin at 30mg/day reduced the incidence of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients.100 An additional group that is appropriate for skin cancer chemo-prevention includes patients with premalignant lesions and a history of 1 or a few skin cancers. Vitamin A (25 000IU per day) appears to benefit patients with many actinic keratoses and a history of fewer than 3 skin cancers101 but not those with 4 or more cancers.102 Albeit retinoids have shown promise as skin cancer chemo-prevention agents, their benefits do not persist after discontinuation of treatments. It should be also noted that long-term use is associated with possible severe side-effects and therefore careful patient monitoring is required.

Researchers have reported favourable responses to isotretinoin and etretinate in patients with multiple keratoacanthomas.103, 104 Other studies with patients with SCC were also reported to be successfully treated with oral isotretinoin.105 However, in most cases responses of advanced skin cancers to retinoids have been largely disappointing.

Vitamin C (Ascorbate)

Ascorbate has a known catalytic role and hence is a co-factor for a number of enzymes. Most cutaneous manifestations of ascorbate deficiency (scurvy) can be attributed to its role as a cofactor for prolyl and lysyl hydroxylase. Ascorbate plays a critical role in wound healing.106

Moreover, ascorbate has the potential to act as a photo-protectant. Skin damage caused by UV radiation includes acute events like sunburn and photosensitivity reactions as well as long-term exposure events that can lead to photo-ageing and skin cancer. It is important to note that ascorbate levels of the skin can be severely depleted after UV irradiation.107

Vitamin C has been reported to protect the skin from UVA-mediated and UVB-mediated phototoxic reactions,108, 109 and when it is combined with a UVA sunscreen, a greater than additive protection is noted. Reduced sunburn reaction, measured by minimal erythema dose and cutaneous blood flow, has also been reported in human studies after systemic administration of 2g vitamin C and 1000IU of vitamin E for 8 days.110 Orally administered vitamin C has been shown to protect mice from UV induced dermal neoplasms. These studies have reported that increases in dietary vitamin C decreased the incidence and delayed the onset of malignant lesions.111, 112

Numerous reviews have consistently reported on studies that have demonstrated that ascorbate can be photo-protective and aid skin repair.113–118

Vitamin E

Vitamin E includes tocopherols and tocotrienols and is a putative antioxidant with no known catalytic roles. However, given that it is a fat soluble (lipophilic) vitamin, it may have important intracellular metabolism modifying functions.118

Skin damage, UV radiation

Research has demonstrated that topically applied alpha-tocopherol can inhibit thymine dimer formation after UVB irradiation in a dose-dependent manner, providing a mechanism through which vitamin E can prevent gene mutations and thus development of skin cancer.119 Vitamin E hence, can be topically applied to skin protecting it from UV-induced damage.

Topical application to the skin of laboratory animals (mice), with vitamin E, has demonstrated a significant benefit immediately after UVB exposure to reduce sunburn-associated erythema, oedema, and skin sensitivity.120 Also chronic photo-damage, assessed by skin wrinkling and tumour development, has also been shown to be delayed by topical application of 5% tocopherol before UVB exposure.121 The efficacy in humans is contentious.

In contrast, a study by Werninghaus and colleagues122 has reported that daily supplementation of healthy individuals with 400IU of natural-source vitamin E for up to 6 months did not significantly alter UV-induced skin damage, as assessed by minimal erythema dose and sunburn cell formation.

A recent review123 has cited numerous topical studies (laboratory animal and human studies) that have demonstrated that vitamin E application prior to UV exposure significantly reduced:

Early uncontrolled trials, using topical application of vitamin E have demonstrated relief of pain and aided in the healing of oral herpetic lesions (gingivostomatitis or herpetic cold sores). In 2 studies, the affected area was dried and cotton saturated with vitamin E oil (20 000–28 000IU per ounce) was spread over the lesions for 15 minutes.124, 125 Pain relief was noted within 15 minutes to 8 hours, and the lesions regressed more rapidly than normal. In some cases, a single application was beneficial, but large or multiple lesions responded better when treated 3 times daily for 3 days. In a further study of 50 patients with herpetic cold sores, the content of a vitamin E capsule was applied to the lesions every 4 hours. The results of this study126 demonstrated prompt and sustained relief of pain and the lesions healed more rapidly than was otherwise expected.

Vitamin D

Psoriasis

Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common type of psoriasis and is characterised by redness, thickness and scaling. A recent systematic review that investigated the efficacy of cortecosteroid medication and vitamin D on chronic plaque psoriasis has concluded that dithranol and tazarotene performed better than placebo and that comparisons of vitamin D against potent or very potent corticosteroids found no significant differences. However, combined treatment with vitamin D/corticosteroid performed significantly better than either vitamin D alone or corticosteroid alone.127

Calcipotriol, a vitamin D analogue (and a synthetic derivative of calcitriol), has been reported in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of supervised treatment of psoriasis in a day-care setting can be considered as a first-line approach in clinical practice.128 Patients who participated in this multi-centre clinical trial were treated at the day-care centre, using the care instruction principle of daily visits during the first week and twice-weekly visits subsequently for up to 12 weeks. The study concluded that topical treatment in combination with interventions explicitly focusing on improvement of coping behaviour and psychosocial functioning may further increase the degree of improvement in the psychosocial domains of quality of life in this patient group.

Recently a clinical trial reported that calcitriol ointment at a concentration of 3μ/g was a safe, effective, and well-tolerated option for the long-term treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Clinical improvement was maintained for up to 52 weeks, with no clinical effect on calcium homeostasis or other relevant laboratory test parameters observed.129

Atopic dermatitis

In a recent double-blinded randomly assigned pilot study participants took ergocalciferol 1000IU or an identical-looking placebo once daily for 1 month for winter-related atopic dermatitis in children.130 Four out of the 5 child participants who received vitamin D compared with 1 out of the 5 who received placebo had a documented improvement but the difference was not statistically significant when the differences between baselines for the 2 groups were calculated. A study with larger participant numbers is required. The role of vitamin D in inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis in children remains to be elucidated. Recently the American Academy of Paediatrics in the US recommended an increase to the daily dose of vitamin D in children from 200 to 400IU per day.131 Noticeable effects, on the incidence of atopic dermatitis hence remain to be reported.

Skin cancers and malignant melanomas

New scientific findings convincingly demonstrate that Vitamin D deficiency is associated with a variety of severe diseases including various types of cancer.132 Hence sun exposure has been reported from various locations 133–136 to be associated with a relatively favourable prognosis and increased survival rate in various malignancies, including malignant melanoma. A recent meta-analysis concluded that there is a growing body of evidence that Vitamin D may be of significant importance for the pathogenesis of cutaneous malignant melanoma.137

B Group Vitamins

Sporadic studies have been reported in the scientific literature which investigated the topical application of specific B group vitamins to the skin. Topical nicotinamide, the physiologically active form of niacin, was reported to have efficacy comparable to that of topical clindamycin in the treatment of acne vulgaris138 and has produced good results in patients with necrobiosis lipoidica.139 In combination with tetracycline, nicotinamide was successful in 1 patient with dermatitis herpetiformis.140 The combination of nicotinamide and tetracycline has also been proposed as an alternative to systemic steroids in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid.141 The success of nicotinamide in the treatment of these skin disorders perhaps is attributable to a re-regulation of the inflammatory state of the skin.

Other B-complex vitamins that have been used in the treatment of skin disorders include pyridoxine, for the management of erythropoietic protoporphyria,142 and vitamin B12, in combination with folic acid, for the treatment of vitiligo.143

Minerals

Zinc

Zinc is an essential component of many metallo-enzymes involved in cell activities such as protein synthesis DNA and RNA replication, and cell division and it is crucial for the normal development of the skin.144

Acne volgaris

Studies detecting low serum zinc levels in patients with acne have a long history.145,146 The finding that zinc was bacteriostatic against Propionibacterium acnes, inhibited chemotaxis, and could decrease tumour necrosis factor-alpha production provided evidence of its usefulness. Subsequently numerous studies have demonstrated that oral zinc was effective in the treatment of severe and inflammatory acne,147–153 more so than it was for mild or moderate acne.154, 155

Gastrointestinal side-effects can be ameliorated somewhat by ingesting zinc directly after meals. One to 2 milligrams of copper supplementation may be recommended with long-term zinc therapy to prevent copper deficiency as zinc decreases the absorption of copper. Oral zinc salt supplementation has been shown to be equally or less effective than oral tetracyclines.156–159

One study, however, showed that oral zinc sulfate had no effect on male patients with moderate acne after 8 weeks of therapy, despite evidence of systemic absorption.160 Limited efficacy and poor patient compliance caused by gastrointestinal side-effects have limited the use of oral zinc for the treatment of acne. Further trials need to be conducted to assess the efficacy and side-effects of lower doses of orally administered zinc.

Selenium

Selenium has a catalytic role, as a component of glutathione peroxidase, in the regulation of oxygen metabolism, particularly in catalysing the breakdown of H2O2. Studies with laboratory animals have implicated selenium deficits in skin cancer tumorigenesis.162 Human studies however have proven controversial.

Cancer studies

Early clinical studies have demonstrated that skin cancer patients in good general health had a significantly lower mean plasma selenium concentration than did controls, and have reported that serum selenium is predictive of future skin cancer risk in humans.163, 164 A multicenter RCT from the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group, demonstrated that selenium treatment (200mg) of skin cancer patients for 4.5 years reduced significantly total cancer incidence and mortality and incidences of lung, colorectal, and prostate cancer, but it did not protect against development of another basal or squamous cell carcinoma.

Investigators emphasised the need for confirmation of their results before new public health recommendations regarding selenium supplementation could be made.165

A recent Cochrane review has confirmed this notion.166

In a recent study on the effect of selenium intake on the prevention of cutaneous epithelial lesions in organ transplant recipients it was reported that selenium (at a dose of 200 μg/day) did not prevent the occurrence of skin lesions linked to HPV.167

Recent zinc/selenium trace element supplementation studies have demonstrated significant associations with higher circulating plasma and skin tissue contents of zinc/selenium and improved antioxidant status. These physiological changes were associated with improved clinical outcome, including fewer pulmonary infections and better wound healing.168, 169

Other nutritional supplements

Alpha-hydroxy acids (AHAs)

Acne vulgaris

Studies have demonstrated that AHAs are safe and efficacious, in combination, such as in glycolic acid/retinaldehyde preparations,170, 171, 172 as well as its ability to accompany common topical anti-acne therapies. Also, this combination has been reported to prevent and repair post-inflammatory hyper-pigmented skin that was associated with acne.173 Retinaldehyde, a precursor of retinoic acid, has shown de-pigmenting activity whereas glycolic acid decreases excessive pigmentation by a wounding and re-epithelization process. There appears to be a synergistic effect when these 2 compounds are used in combination.

An early double-blind clinical trial on 150 patients to evaluate the efficacy and skin tolerance of the alpha hydroxy acid gluconolactone 14% in solution (Nuvoderm lotion) in the treatment of mild to moderate acne was compared to its vehicle (placebo) and 5% benzoyl peroxide lotion. The results of the study demonstrated that both gluconolactone and benzoyl peroxide had a significant effect in improving patients’ acne by reducing the number of lesions (i.e. inflamed and non-inflamed). Furthermore, fewer side-effects were reported by patients treated with gluconolactone when compared with benzoyl peroxide.174 Irritation was the main adverse effect when gluconolactone was in high concentrations.

Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is a phytohormone, a plant product that acts like a hormone by regulating cell growth and differentiation. It is a beta hydroxy acid that is chemically similar to the active component of aspirin. It functions as a topical desquamating agent, dissolving the intercellular cement holding the cells of the stratum corneum together. It is used as a topical keratolytic agent.

Hyperpigmentation

A recent small study of 10 participants with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV to VI were randomised to receive two 20% salicylic acid peels followed by three 30% salicylic acid peels to half of the face. The contralateral half of the face remained untreated.175 The results of this study demonstrated that salicylic acid peels were safe in this population of adults. Measured quality of life improved nominally.

Acne vulgaris

In an RCT study, 80 participants with mild to moderate facial acne were randomised to receive either a lipophillic derivative of salicylic acid formulation twice a day or 5% benzoyl peroxide once a day for 12 weeks. The study compared efficacy and tolerance between the treatments for facial acne vulgaris and reported that the lipophillic derivative of salicylic acid formulation could be a treatment option to consider in mild to moderate acne vulgaris patients that are intolerant to benzoyl peroxide.176

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

CoQ10 is ubiquitous in human tissues, although its level is variable. The level of CoQ10 is highest in organs with high rates of metabolism such as the heart, kidney and liver.177 Compounds such as coenzyme Q10 have been reported to play an increasing beneficial role in skin care. The benefits range from skin conditions such as acne and psoriasis to protection against environmental insults.178

Psoriasis

A recent study that evaluated the clinical effects of supplementation with antioxidants to patients with severe erythrodermic and arthropathic forms of psoriasis reported that co-supplementation with antioxidants such as vitamin E, and selenium plus CoQ10 could be feasible for the management of patients with severe forms of psoriasis.179

The use of CoQ10 has also been heavily promoted for use in cosmeceutical products as a beneficial agent for ageing skin.180, 181

Lipoic acid

Low molecular weight compounds such as lipoic acid have also been reported to be protective low molecular weight antioxidants through a diet rich in fruits and vegetables or by direct topical application for photo-damaged skin.182 However, studies investigating the efficacy of lipoic acid in treating photo-damaged skin are lacking.

Functional foods

Probiotics

A recent review has documented the numerous experimental studies that have found that probiotics exert specific effects in the intestinal lumen and on epithelial cells and immune cells with anti-allergic potential.183 The review also documented that the barrier function and the innate immune system of the skin indicates that the skin’s microbiota have a beneficial role, much like that observed with the gut microflora.184

Atopic dermatitis

Studies worldwide have shown that an environment rich in microbes in early life reduces the subsequent risk of developing allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis.185 Continuous stimulation of the immune system by environmental saprophytes via the skin, respiratory tract and gut appears to be necessary for activation of the regulatory network including regulatory T-cells and dendritic cells. Substantial evidence now shows that the balance between allergy and tolerance is dependent on regulatory T-cells. Tolerance induced by allergen-specific regulatory T-cells appears to be the normal immunological response to allergens in non-atopic healthy individuals. Healthy subjects have an intact functional allergen-specific regulatory T-cells response, which in allergic subjects is impaired. Evidence on this exists with respect to atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma.

In a large meta-analysis of the current literature regarding the use of prenatal and postnatal probiotics for the prevention and treatment or either of atopic dermatitis, Lee and colleagues have reviewed and analysed the data from 10 studies.186 Six of the 10 studies showed evidence to support the use of probiotics both prenatally and postnatally for the prevention of atopic dermatitis. A risk reduction as high as 61% was seen that was attributed mainly to the prenatal use of probiotics. For the treatment of atopic dermatitis there was no significant difference detected between those that used probiotics and those that did not. Patient education may further increase the likelihood of successful preventative measures.187

Eczema

Probiotic bacteria have been proposed as an effective treatment for eczema, and recently a number of clinical trials have been undertaken and recent systematic reviews have analysed the published data. Two reviews by the same research group have found that there was significant heterogeneity between the results of individual studies, which could be explained by the use of different probiotic strains.188,189 A subgroup analysis by age of participant, severity of eczema, presence of atopy or presence of food allergy did not identify a population with different treatment outcomes to the population as a whole. The adverse events reported identified some case reports of infections and bowel ischaemia caused by probiotics. The overall conclusions from the reviewed was that probiotics were not an effective treatment for eczema, and probiotic treatment carried a small risk of adverse events.

Essential fatty acids (omega-3 and -6)

Atopic dermatitis

There has been conflicting evidence on the use of omega-3 and omega-6 supplementation for the prevention of allergic diseases. A recent systematic review has investigated RCTs and contrary to the evidence from basic science and epidemiological studies, the review suggested that supplementation with omega-3 and omega-6 oils was unlikely to play an important role as a strategy for the primary prevention of sensitisation or allergic disease.190 The evidence hence remains highly contentious as it is out of line with the plethora of additional data that is available.191–194

Herbal medicines

Herbal medicines that are used as medicines comprise plants/plant part(s) that contain specific active ingredients that enable it to be used for healing purposes or symptom relief. There are a number of herbs that have been reported to have traditional uses for skin problems and these include examples such as chamomile, fennel, lavender, lemon balm, pot marigold, red clover, rose, sage and thyme.195 The following discussion follows the use of herbal medicines by treatment type.

Herbal medicines for acne

The topical application and oral ingestion of herbal medicines and plants that have been indicated for acne problems and with anti infective properties such as that produced by P acnes are presented in Tables 14.5 and 14.6.196, 197

Table 14.5 Topically applied herbal medicines and plants/plant parts for the treatment of acne, condyloma and verruca vulgaris

| Aloe vera/Aloe Barbadensis | Ironweed/Veronia antihelminitica |

| American may apple/Podophyllum peltatumΦ | Kramiria triandra Ruis plus escin–beta–sitosterol plus lauric acid |

| Bittersweet nightshade/Solanum dulcamaraΦ | Lilac/Azadirachta indicaΩ |

| Black walnut/Juglans regia | Oak bark/Quercus robur |

| Borage/Borago officinalis | Oat straw/Avena sativaΦ |

| Compositae/Artemesia vulgaris and A. Absinthum | Onion/Allium cepa |

| Calotropis/ Calotropis proceraΦ (used in India to treat warts) | Oregon grape root/Mahonia aquifolia/ berberine |

| Crinum/Crinum macowanii | Pea/Pisum sativum |

| Cucumber | Pomegranate/Punica granitum |

| Duckweed/Lemma minor | Pumpkin/Cucurbita pepo |

| English walnut/Juglans regia | Rue/Ruta graveolens |

| Fresh lemon | East Indian globe thistle/Sphaeranthus indicus LΩ |

| Fruit acids (citric/gluconic/gluconolactone/glycolic/malic/tartric) | White Marudah/Ternialia arjuna |

| Garlic/Allium sativum | Tea Tree Oil/Melaleuca alternifoliaΩ |

| Grapefruit seeds | Turmeric/Curcuma longaΩ |

| Greater celandine/Chelidonium majusΦ (used in China to treat warts) | Vinegar |

| Indian Madder/Rubia cordifoliaΩ | Vitex/Vitex agnus–castus L |

| Indian Sarsaparilla/Hemidesmus indicusΩ | Witch-hazel/Hamamelis virginiana sp |

Note: These herbal medicines and plants/plant parts are effective in inhibiting the pathogenesis of P acnesΩ in vitro, in vivo and for condylomaΦ and verruca vulgarisΦ

Table 14.6 Orally administered herbal medicines and plants/plant parts and otherΔ for the treatment of acne

| Burdock root/Arctium lappa |

| ΔBrewer’s yeast/Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

| Ku shen/Sophora flavescens |

| Indian ginseng/Withania somnifera |

| Mukul myrrh tree/ Commiphora mukul |

(Source: modified from Magin et al. 2006)196

It has been reported that tannins (substances present in the seeds and stems of grapes, the bark of some trees, and tea leaves) have been employed topically to treat acne because of their natural astringent properties.198 A herb that is known for its astringent and anti-viral properties is witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). This herb is from a genus of flowering plants in the family Hamamelidaceae, with 2 species in North America (H virginiana and H vernalis), and 1 each in Japan (H. japonica) and China (H mollis).199, 200 There are no studies that have reported the efficacy of witch-hazel in the treatment of acne.

Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia)

Tea tree oil was studied in an early Australian study201 by comparing the efficacy of 5% tea tree oil to that of 5% benzoyl peroxide. A single-blinded, RCT on 124 patients was performed to evaluate the efficacy and skin tolerance of 5% tea tree oil gel in the treatment of mild to moderate acne. The study concluded that both preparations, namely 5% tea tree oil and 5% benzoyl peroxide, had a significant effect in ameliorating the patients’ acne by reducing the number of inflamed and non-inflamed lesions (i.e. open and closed comedones), although the onset of action in the case of tea tree oil was slower. Also fewer side-effects were reported by patients treated with tea tree oil. A further study supported the use of tea tree oil in the treatment of acne, and demonstrated that the terpinene-4-ol was not the sole active constituent of the oil that may have antimicrobial activity.202 A subsequent systematic review, although not finding conclusive evidence that tea tree oil was useful in the treatment of acne, did specify that the emerging evidence was promising.203, 204

Tea tree oil has been recently studied in a double-blind RCT of 60 patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris.205 Participants were randomly divided into 2 groups and were treated with tea tree oil gel (n = 30) or placebo (n = 30) and were followed every 15 days for a period of 45 days. The study concluded that topically applied 5% tea tree oil is an effective treatment for mild to moderate acne vulgaris.

Tea tree oil may also have additional effects on the skin as reported recently with the first study to show experimentally that tea tree oil reduced histamine-induced skin inflammation.206

Vitex (Vitex agnus castus L)

The traditional use of this herb has been reported to be for the efficacious treatment of premenstrual acne.207, 208 The whole fruit extract is thought to act to rebalance follicle stimulating hormone and luteinising hormone levels in the pituitary gland therby increasing progesterone and simultaneously decreasing oestrogen levels.207 The German Commission E Monographs (hereafter referred to as the German Commission) have recommended an oral dose of 40mg/day.209 The main adverse effects reported were gastrointestinal upset and rash. From the published scientific data, Vitex has been recently reported to be a safe medicinal herb.208 There is though a requisite for more controlled studies to demonstrate the efficacy of this herb.

For an extensive review that has recently documented the extensive literature on herbal medicines for the treatment of acne refer further to the review by Magin and colleagues.196

Herbal medicines for wounds, burns and radiation dermatitis

Aloe vera

Several case reports have documented that Aloe vera reduced itching, burning and scarring associated with radiation dermatitis.210 An early study demonstrated that Aloe vera was effective in skin wound caused by burns.211 This study showed the effectiveness of Aloe vera gel on a partial thickness burn wound, concluding that additional studies were warranted. Also, that only some minor adverse effects, such as discomfort and pain were encountered in the 27 cases.

A recent systematic review while accepting that Aloe vera has been traditionally used for burn healing the clinical evidence for its efficacy remains unclear.212 The study concluded that due to the differences of products and outcome measures employed by different study designs, there was paucity of information and hence to draw specific conclusions regarding the effect of Aloe vera for burn wound healing was difficult. However, the authors did also comment that given the cumulative scientific evidence that exists, this would tend to support that Aloe vera might be an effective intervention used in burn wound healing for first to second degree burns. Moreover it was also concluded that well-designed trials with sufficient details of the contents of the Aloe vera products used (percent content of the gel and liquid extracts) should be carried out to determine the efficacy of the herb.

Honey

For centuries the use of honey has provided a therapeutic ointment option for wounds.213 There is a growing body of scientific literature promoting the use of sterilised honey-based products in wound care, demonstrating their efficacy, cost-effectiveness and exceptional record of safety.214, 215

A recent Cochrane review concluded that honey may improve healing times in mild to moderate superficial and partial thickness burns compared with some conventional dressings.216

Marigold (Calendula officinalis)

Marigold has been used topically for skin wounds for centuries. The German Commission has approved its use as an antiseptic for wound healing.209

A number of studies have reported that Calendula officinalis was effective in treating radiation induced wounds in cancer patients.217, 218, 219

A recent systematic review has demonstrated preliminary data in support of the efficacy of topical calendula for prophylaxis of acute dermatitis during radiotherapy.220

Tannins in herbs

Common tannin-containing herbs that may be useful for treating skin wounds when topically applied include English walnut leaf (Juglans regia), goldenrod, Labrador tea, lavender, mullein, oak bark, rhatany, Chinese rhubarb and yellow dock.207 The efficacy for these herbal medicines is largely anecdotal and good quality trials are required.

Herbal medicines for skin wounds due to herpes simplex

Lemon balm (Melissa Oficinalis L)

Extracts of the leaves of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) have been investigated as a topical treatment for herpes simplex. Randomised trials have demonstrated that Lemon balm was effective for herpes simplex. In 1 study with 116 patients with an acute herpes simplex outbreak applied a lemon balm preparation or a placebo cream. Treatment was begun within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms and administered 2–4 times daily for 5–10 days. Healing was assessed as very good by 41% of patients in the lemon balm group and by 19% in the placebo group.221 A further study which was a DBRCT was carried out with the same balm preparation with the aim of proving efficacy of the standardised balm mint cream (active ingredient: 1% Lo–701 dried extract from Melissa officinalis L leaves [70:1]).222 The lemon balm cream or placebo cream was applied to the affected area 4 times daily for 5 days. On the second day of therapy, the symptom score was significantly lower in the active-treatment group than in the placebo group, with a non significant trend in favour of the lemon balm treatment at the end of the study.

Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra and Glycyrrhiza uralensis)

The topical application of Glycyrrhiza sp has been associated with historical sources from ancient manuscripts from China, India and Greece.223 Laboratory studies have demonstrated inhibition of the varicella zoster virus. Human clinical trials have yet to be conducted, although the topical application of liquorice is reported to be safe.207

Herbal medicines for bacterial and fungal infections

As previously outlined a number of herbal medicines can inhibit the growth of P acnes in vitro (Table 14.5).197 Similarly tea tree oil has demonstrated significant antibacterial activity in vitro against a variety of micro-organisms that include, Propionibaterium acnes, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans, Tricophyton mentagrophytes and Trichophyton rubrum.198

Tea tree oil has also been used as a topical antiseptic agent since the early part of the 20th century for a wide variety of skin infections, including bacterial and fungal.224 In a study with a fungal infection tea tree oil cream (10% w/w) appeared to reduce the symptomatology of tinea pedis as effectively as tolnaftate 1% but was no more effective than placebo in achieving a mycological cure.225 In a further study which assessed the efficacy and tolerability of topical application of 1% clotrimazole solution compared with that of 100% tea tree oil for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis, the study concluded that the topical therapy, provided improvement in nail appearance and symptomatology by both treatments.226 However it was concluded by another study that it should not be employed in burn wounds to the skin because of tea tree oil’s cytolytic effect on epithelial cells and fibrolasts.227

Garlic (Allium sativum)

Reports document that ajoene, an organic trisulphur originally isolated from garlic, has an antimycotic activity which has been widely demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo.228 A study of short duration demonstrated that the use of ajoene as a 0.4% (w/w) cream resulted in complete clinical and mycological cure in 27 of 34 patients (79%) after 7 days of treatment. The remaining 7 patients (21%) achieved complete cure after 7 additional days of treatment.229 At a 3-month follow up all participants remained free of fungus.

Herbal medicines for condyloma and verruca vulgaris

A number of herbal medicines have been reported to treat skin warts (see Table 14.5).198 However, rigorous clinical trials are warranted to test efficacy and safety.

Herbal medicines for scabies

Herbal preparations from essential oils such as anise (Pimpinella anisum) seeds that has displayed antibacterial and insecticidal activity in vitro has been employed topically to treat scabies.198 Neem (Azadirachta indica) is an Indian plant that has been used medicinally in that country.198 In a report of more than 800 villagers in India the paste of neem and turmeric was used topically to treat chronic ulcers and scabies.198 Rigorous data is lacking and further studies are warranted.

Herbal medicines for psoriasis and dermatitis

TCM herbs

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis has gained significant attention in the last decade.198 TCM deals with the whole-body medicine system whereby the role of the therapy is to regain metabolic balance for the individual. This requires a mixture of herbs.230

Two recent cross-over RCTs investigated the use of TCM in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in which conventional medicine had failed to respond adequately to currently available therapies.231, 232

A Chinese practitioner aided the investigators to formulate a mixture of herbal medicines for the RCTs. The Chinese herbal medicines included Potentilla chinensis, Tribulus terrestris, Rehmannia glutinosa, Lophatherum gracile, Clematis armandi, Ledebouriella sacleoides, Dictamnus dasycarpus, Paeonia lactiflora, Schisonepeta tenuifolia and G glabra. This mixture of herbs was placed in sachets and boiled and then provided to participants as a tea to be consumed daily.231 The 2 (8-week) studies investigated children (atopic eczema) and adults (atopic dermatitis) and the mixed herbal tea was significantly more effective than the placebo tea preparation. The efficacy was associated with significant decreases in erythema and surface damage to the skin. The only serious adverse event reported was elevation of aspartate aminotransferase levels in 2 children which decreased to normal on treatment discontinuation.

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, recurrent inflammatory skin disorder whose aetiology is still unknown. Traditional Chinese herbal medicines have demonstrated efficacy in treating psoriasis, with TCM characterised by a variety of methods of treatment, flexible use of drugs, high efficacy, low recurrence, and few side-effects.233, 234 A recent study with 80 patients randomly assigned to 2 groups, 39 in Group A and 41 in Group B, investigating blood-heat syndrome type psoriasis has demonstrated that the effect of Chinese herbal medicines combined with acitretin capsule was superior to Chinese herbal medicines alone in treating this skin problem.235 This result, though, requires replication by conducting larger trials.

Aloe vera

As discussed previously, Aloe vera has a historical use for treating skin wounds. In an early double-blind RCT study 60 patients were treated with a topical Aloe vera extract 0.5% in a hydrophilic cream to cure patients with psoriasis vulgaris.236

The results from this study suggest that topically applied Aloe vera extract 0.5% in a hydrophilic cream is more effective than placebo. No toxic or any other objective side-effects were demonstrated hence the regimen was deemed as safe and as an alternative treatment to cure patients suffering from psoriasis. A systematic review that followed this study concluded that even though there were some promising results, clinical effectiveness of oral or topical Aloe vera was reported not to be sufficiently defined.237

A recent double-blind RCT reported the effect of the commercial Aloe vera gel on stable plaque psoriasis to be modest and not better than placebo. However, the high response rate of placebo indicated a possible effect of this in its own right, which would make the Aloe vera gel treatment appear less effective.238

Capsaicin (Capsicum frutescens)

Capsaicin is the active component of cayenne peppers (chilli peppers). Two early trials have demonstrated that 0.025% capsaicin cream was effective in treating psoriasis.239, 240 One study showed significant reductions in scaling and erythema during a 6-week treatment of 44 participants presenting with moderate to severe psoriasis.237 The second study was a double-blind study in patients with pruritic psoriasis randomised to receive either the capsaicin cream or vehicle 4 times a day for 6 weeks.220 Topically applied capsaicin effectively treated pruritic psoriasis.

A review that followed these studies concluded that capsaicin was effective for psoriasis.241

Reported side-effects include a short-lived burning sensation. The German Commission suggest that capsaicin not be used for more than 2 consecutive days with a 2 week lapse between consecutive treatments.198

St Johns wort (Hypericum perforatum L)

A recent double-blind RCT study with a cream containing Hypericum extract standardised to 1.5% hyperforin (verum) in comparison to the corresponding vehicle (placebo) for the treatment of subacute atopic dermatitis.242 The study concluded that the Hypericum cream showed a significant superiority compared to the vehicle in the topical treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. However, the therapeutic efficacy has to be evaluated in further studies with larger patient cohorts, in comparison to therapeutic standards such as glucocorticoids.

Other herbal medicines

A number of herbs have been approved by the German Commission for the use in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. These include: Arnica montana, German chamomile (Matricaria recutita), bittersweet nightshade (S. dulcamara), as we all as Breyer’s yeast (S. cereviceae) which are thought to possess anti-inflammatory activity and anti-bacterial effects. Heartseases (Viola tricolor), English plantain (Plantago lanceolata), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-gaecum), and flax (Linum usitatissium) contain mucilages which can act as emollients that can soothe the skin.198 Furthermore, agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria), oak (Quercus robur), walnut (Juglans regia), and St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) contain tannins and can act as astringents. Oak straw (A. sativa) was also approved for its soothing and antipruritic qualities.198

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy is the therapeutic use of volatile, aromatic essential oils which are extracted from plants. Aromatherapy may also be regarded as having a close and overlapping relationship to herbal medicine. Aromatic compounds have been used throughout history for spiritual, medicinal, social, and beauty purposes.243

The aromatic oils depicted in Table 14.7 have been reported to be useful in a variety of dermatological conditions especially acne.242 Further, there are only a few clinical trials that have been published on the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis with herbal ointments and the quality of these trials was largely poor. Whereas a review of clinical trials with Mahonia aquifolium reported that taken together, these clinical studies indicated that Mahonia aquifolium was a safe and effective treatment for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis.244

Table 14.7 Aromatherapy — essential oils useful in dermatology

| Australian eucalyptus/Eucalyptus radiata |

| Basil/Ocimum sactum, O basilicum and O gratissimum |

| Bay essential oil/Pimenta racemosa |

| Benzoin/Styrax benzoe |

| Black cumin/Nigella sativa |

| Black pepper/Piper nigrum |

| Benzoin/Styrax benzoe |

| Bergamot/Citrus bergamia |

| Cajeput/Melaleuca leucodendron |

| Chamomile/ Chamaemelum nobile |

| Dandelion/Taraxacum officinale |

| Frankincense/Boswellia carterii |

| Fijian fire plant/Acalypha wilkesiana |

| German chamomile/Matricaria recutita |

| Geranium/Pelargonium asperum |

| Heartsease/Viola tricolor |

| Holly-leaved barberry/Mahonia aquifolium |

| Jasmine/Jasminum officinalis |

| Juniper berry/Juniperus communis |

| Juniper twig/Juniperus communis ram |

| Knight’s milfoil/Achillea millefolium |

| Lavender (true)/Lavandula angustifolia and L. spicula |

| Lavender (French)/Lavandula latifolia |

| Lemon grass/Cymbopogon citratus |

| Lemon/Citrus limon |

| Nialouli/Melaleuca quinquenervia/Viridifolia |

| Orange/Citrus aurantium |

| Orange (sweet)/Citrus senesis |

| Patchouli/Pogostemon cablin |

| Petitgrain/Citrus aurantium var amara fol |

| Peppermint/Mentha x piperita |

| Moroccan chamomile/Ormensis mixta flos |

| Ravensara/Ravensara aromatica |

| Rose water/Rosa damascena |

| Rosemary (verbenone)/Rosmarinus officinalis |

| Safflower oil, Linoleic acid |

| Sandalwood/Santalum album and S. spicatum |

| Scotch pine/Pinus sylvestrus |

| Sunflower oil, linoleic acid |

| Tea tree oil/Malaleuca alternifolia |

| Thick-leaved pennywort/Centella asiatica |

| Thyme linalool/Thymus vulgaris L. |

| Verbenone/Rosemarinus officinalis verbenone |

| Winter Savory/Satureja montana |

A reported RCT of a Toto ointment/soap combination (containing Shea butter/Butyrospermum paradoxicum oils with multiple constituents) reported efficacy after an average of approximately 4 weeks of treatment.245 The RCT was of a poor quality.

A further low-quality, open, non-comparative study was of the efficacy and safety of Acalypha wilkesiana ointment in superficial fungal skin diseases. Thirty-two Nigerian patients with clinical and mycological evidence of superficial mycoses were recruited. The study concluded that Acalypha ointment may be used for the treatment of superficial mycoses.246

A recent study with a combination herbal ointment containing Mahonia aquifolium, Viola tricolor and Centella asiatica was reported for the treatment of mild–moderate atopic dermatitis.247 Patients were treated for 4 weeks with the ointment. The primary endpoint was a summary score for erythema, edema/papulation, oozing/crust, excoriation and lichenification according to a 4-point scale. The study concluded that the ointment was not proven to be superior to a base cream. However, a sub-analysis of the data indicated that the cream could be effective under conditions of cold and dry weather.

Low level quality studies investigating Ocimum gratissimum oil products tested were reported to produce a significantly greater reduction in acne lesion count compared with 10% benzoyl peroxide.248, 249, 250

A recent review has investigated the literature and the evidence that exists on the influence that essential oils have on wound healing and their potential application in clinical practice.251 The review concludes that although there is some evidence for efficacy for such essential oils as further larger studies are required.

Herbal medicines for alopecia

Garlic gel/betamethasone valerate

A recent double-blind RCT study investigated a combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localised alopecia areata.252

Aromatherapy oils

The efficacy of aromatherapy in the treatment of patients with alopecia areata was investigated in an RCT.253 Eighty-six patients diagnosed as having alopecia areata were randomised into 2 groups. The active group massaged essential oils (thyme/rosemary/lavender/cedarwood) in a mixture of carrier oils (jojoba/grapeseed) into their scalp daily whereas the control group used only carrier oils for their daily massages for 7 months. The results demonstrated aromatherapy safety and efficacy of treatment for alopecia areata. Treatment with these essential oils was significantly more effective than treatment with the carrier oil alone.

Physical therapies

Electrical impulses

A recent review of the literature concludes that electrical stimulation of chronic wounds may be efficacious in some instances and that the evidence suggests it is a potentially useful, accessible and cheap therapy, which could play a valuable role in everyday clinical practices.260 A systematic review, however, has concluded that there was no evidence of benefit in using electromagnetic therapy to treat pressure ulcers.261

Acupuncture

Acupuncture has been demonstrated to influence neurologic, endocrine, immune, and psychologic systems. In dermatology numerous acupuncture methods are recognised (Table 14.8).262

Table 14.8 Different forms of acupuncture used in dermatology

| Type of acupuncture | Methodology employed |

|---|---|

| Corporal acupuncture | Involves needling with metal needles on 365 known points, located on the so-called meridians (Chinese Jing Luo) |

| Auricle acupuncture | Richly innervated area consisting of 130 points on the auricle that can evoke various changes in the physiological functions of the body |

| Electro-acupuncture | Consists of electric stimulation using a light electric current with different frequencies. This is applied to the needles influencing the skin and underlying tissues in the region of the acupuncture point |

| Electro-puncture | Effect is rendered directly with electric current by means of electrodes inserted into the acupuncture point. The effect with this method is more superficial compared to electro-acupuncture |

| Moxibustion | Cones are placed on the acupuncture point — wormwood or the wormwood cigar is held at a distance (pecking method), which results in burning or warming of the skin up to 45°C |

| Acupressure |

(Source: adapted from Iliev)262

Acupuncture includes original acupuncture (acus-puncture) and many related methods such as the use of moxibustion, cupping, acupressure and can be divided according to the use or absence of needles.262

Acne

Acupuncture for acne has been reported in a review of TCM applications.263 A recent small study with He–Ne laser auricular irradiation plus body acupuncture for acne vulgaris reported a significant benefit.264 The results showed that the cure rate was approximately 80% in the treatment group and 47% in the control group indicating that He–Ne laser auricular irradiation plus body acupuncture may exhibit better effects for acne vulgaris.

A recent RCT from China that investigated 26 patients with acne conglobata treated by encircling acupuncture combined with ventouse and cupping demonstrated efficacy.265 The study concluded that both acupuncture and medication effectively promoted the recovery of the affected skin, and lowered serum IL-6 levels in acne conglobata patients. The effect of acupuncture was stronger than that of isotretinoin in lowering serum IL-6 content and was associated with fewer adverse effects.

A review article also from China has concluded that acupuncture–moxibustion was safe and effective for treatment of acne, and that it was possibly better than routine Western medicine. Moreover, that the comprehensive acupuncture–moxibustion therapy was better than single acupuncture–moxibustion therapy.266 These data need to be further evaluated.267

Herpes zoster

An early study that investigated a total of 62 cases diagnosed with herpes zoster were enrolled in a single-blinded RCT that evaluated the effect of auricular and body acupuncture compared with placebo. The results showed that 7 patients in the placebo group and 7 patients in the acupuncture group experienced pain relief at the end of treatment. There was no difference in the pain relief between these 2 groups.268

A recent review from China indicates that correct randomisation, concealment, blinding and placebo-control, and the RCTs with generally accepted criteria for assessment of diagnosis and therapeutic effects, safety evaluation and rational design of follow-up are needed. Also, that preliminary studies identified in the scientific literature indicate that blood-letting acupuncture and cupping at Ashi points are the predominant methods for the treatment of herpes zoster.269

Psoriasis

An early study progressed the use of acupuncture as a treatment option for psoriasis.270 Using filiform needle acupuncture to stimulate a number of key points and related acu-points, this study investigated 61 patients with psoriasis who had poor response to Western medical management. Subsequent to an average of 9 sessions of acupuncture treatment, approximately 50% of the 61 patients had complete or near-complete clearance of their skin lesions, approximately one-third had partial improvement, and 15% did not improve. This study’s results are weakened by the lack of a control group however, the results were considered important at the time.

A subsequent Swedish study reported that classical needle acupuncture was not superior to sham therapy in the treatment of psoriasis.271 Though methodologically more robust, the primary weakness of this study was its lack of description in terms of acupuncture points and techniques employed. In addition, the sample size was small with 35 participants receiving acupuncture, and 19 receiving sham acupuncture.

A recent multi-centre study from China and review of the literature has reported that the meridian three-combined therapy was effective and safe for treatment of ordinary psoriasis.272 Hence, this multi-centre, randomised and positive drug controlled trial consisted of 233 cases that were divided into an observation group of 116 cases and a control group of 117 cases. The observation group was treated with thread embedding at points, blood-letting puncture on the back of the ear and auricular point pressing (i.e. meridian three-combined therapy).

Atopic dermatitis

Small early studies have demonstrated some efficacy for atopic dermatitis, however more robust research is warranted.273, 274

Urticaria

Acupuncture has been reported to be effective for both acute and chronic urticaria.275

A recent study from China has reported that acupuncture had a benign regulatory effect on IgE, showing a favourable regulation on the immune functions in patients with chronic urticaria.276

A subsequent study also from China investigated the therapeutic effects of acupuncture plus point-injection for obstinate urticaria.277 Sixty-four cases of obstinate urticaria were randomly divided into 2 groups. The results demonstrated that the therapeutic effect in the treatment group was significantly better than that in the control group, with a much lower relapse rate in the test group than in the control group.

Vitiligo

Briefly vitiligo is a chronic disorder that causes de-pigmentation in patches of skin. A recent study utilising low-energy He–Ne laser therapy induced re-pigmentation and improved the appearance of the skin in segmental vitiligo.278 After an average of 17 treatment sessions, initial re-pigmentation was noticed in the majority of patients. Marked re-pigmentation (> 50%) was observed in 60% of the patients with successive treatments. Furthermore cutaneous blood flow was significantly higher at segmental vitiligo lesions compared with contralateral skin, but this was normalised after He–Ne laser treatment. The study concluded that He–Ne laser therapy was an effective treatment for segmental vitiligo by normalising dysfunctions of cutaneous blood flow and adrenoceptor responses in these patients. It was hypothesized that the beneficial effects of He–Ne laser therapy could be mediated in part by a reparative effect on sympathetic nerve dysfunction.

Other therapies279, 280

Balneotherapy is a natural therapy which makes use of natural elements, such as hot springs, climatic factors, chrono-biological and circadian rhythmic phases and natural herbal substances for treatment of disease. Dermatology perhaps is one of the oldest users of this form of therapy. Wet to dry soaks, salt water baths, tar baths, the use of the Dead Sea for the treatment of many papulosquamous and eczematous disorders — all have been mainstream dermatologic therapy for many decades.281

Phototherapy or light therapy is a form of treatment for skin conditions using artificial light wavelengths from the ultraviolet wavelength range (blue light). A recent study has demonstrated that photo-modulation with a 590 nm wavelength LED array decreased the intensity and duration of post-fractional laser treatment erythema.282

Photopheresis, originally developed in dermatology, has become a treatment method accepted across various disciplines.283

Conclusion

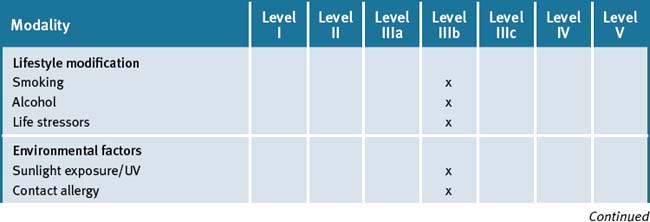

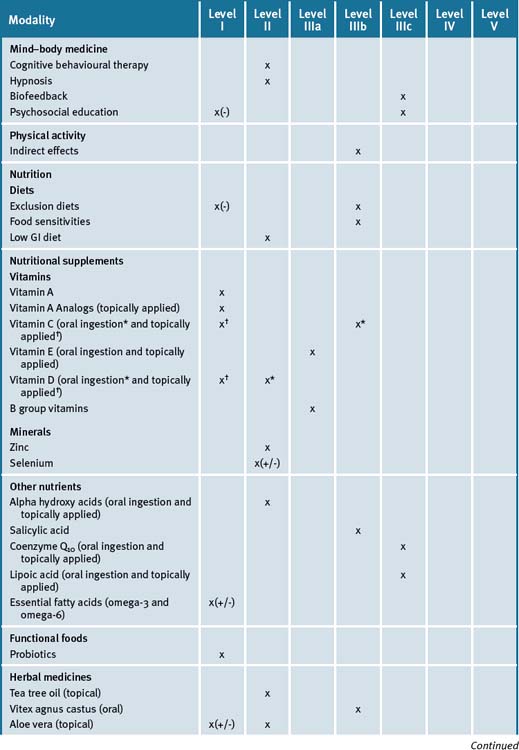

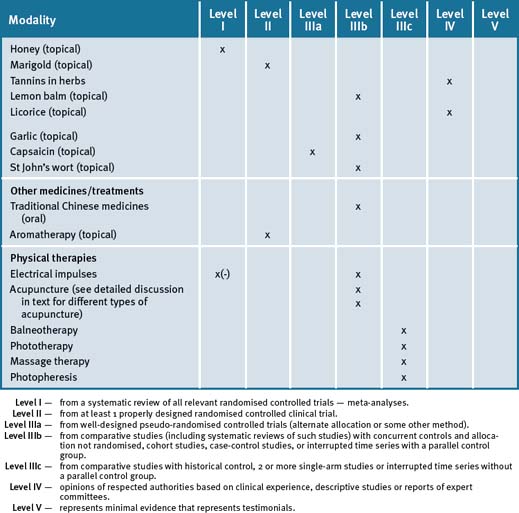

Table 14.9 summarises the level of evidence for some CAM therapies for eczema, psoriasis and other skin disorders.

Clinical tips handout for patients–skin diseases

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

Stress

Rest and stress management

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Multivitamin especially B-group containing B6, B12 and folate

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol 1000IU)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest oral supplementation if levels are low.

Vitamin C and Vitamin E (best given together)

Vitamin C

Zinc

Selenium (sodium selenite, organic selenium found in yeast)

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

Probiotics

Herbal medicines (all for external/topical use only)

Tea tree oil

Aloe vera

Used externally to treat different skin conditions, such as psoriasis, and reduces inflammation.

Used for the treatment of burns and bruises.

Speeds the healing of insect bites, and relieves itching and dandruff.

1 Mukhtar H., Mercurio M.G., Agarwal R. Murine skin carcinogenesis: Relevance to humans. In: Mukhtar H., editor. Skin Cancer: Mechanism and Human Relevance. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1995:3-8.

2 Blanpain C., Fuchs E. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(3):207-217.