Eczema – Basic principles/contact dermatitis

Classification

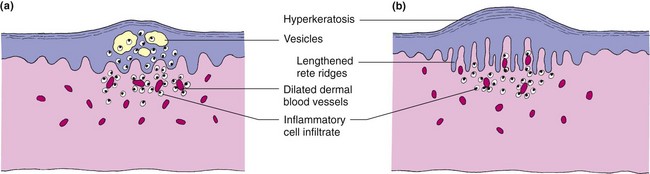

The current classification of eczema is unsatisfactory in that it is inconsistent. However, it is difficult to provide a suitable alternative as the aetiology of most eczemas is not known. Different types of eczema may be recognized by morphology, site or cause. A division into endogenous (due to internal or constitutional factors) and exogenous (due to external contact agents) is convenient (Table 1). However, in clinical practice, these distinctions are often blurred and, not infrequently, the eczema cannot be classified. A further division into acute (Fig. 1) and chronic (Fig. 2) eczema can be made in many cases according to the morphology of the eruption.

| Type | Variety |

|---|---|

| Exogenous (contact) | Allergic, irritant Photoreaction |

| Endogenous | Atopic Seborrhoeic Discoid (nummular) Venous (stasis, gravitational) Pompholyx |

| Unclassified | Asteatotic (eczéma craguelé) Lichen simplex (neurodermatitis) Juvenile plantar dermatosis |

Acute eczema

In acute eczema, epidermal oedema (spongiosis), with separation of keratinocytes, leads to the formation of epidermal vesicles (Fig. 3a). Dermal vessels are dilated, and inflammatory cells invade the dermis and epidermis.

Chronic eczema

In chronic eczema, there is thickening of the prickle cell layer (acanthosis) and stratum corneum (hyperkeratosis) with retention of nuclei by some corneocytes (parakeratosis) (Fig. 3b). The rete ridges are lengthened, dermal vessels dilated and inflammatory mononuclear cells infiltrate the skin.

Contact dermatitis

Definition

Dermatitis precipitated by an exogenous agent, often a chemical, is known as contact dermatitis. It is particularly common in the home, among women with young children and in industry, where it is a major cause of loss of time from work (see p. 124).

Aetiopathogenesis

Irritants cause more cases of contact dermatitis than allergens, although the clinical appearances are often similar. Often, there is an inherited susceptibility to react to irritants. Allergic contact dermatitis is an example of type IV hypersensitivity (p. 11).

Irritants cause dermatitis in a number of different ways, but usually by a direct noxious effect on the skin’s barrier function. The most important irritants are:

Clinical presentation

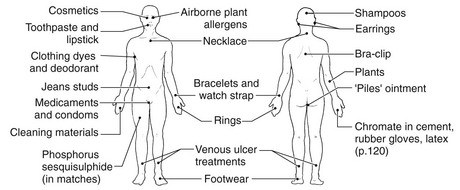

Contact dermatitis may affect any part of the body, although the hands and face are common sites. The appearance of a dermatitis at a particular site (Fig. 4) suggests contact with certain objects. For example, an eczema on the wrist of a woman with a history of reacting to cheap earrings suggests a nickel allergic response to a watchstrap buckle (Fig. 5). Diagnosis is often not easy as a history of irritant or allergen exposure is not always forthcoming. Knowing the patient’s occupation, hobbies, past history and use of cosmetics or medicaments helps in listing possible causes.

Environmental sources of common allergens are shown in Table 2. Medicaments (p. 17) and cosmetics (p. 108) can also induce allergic or irritant reactions. Allergic contact dermatitis occasionally becomes generalized by secondary ‘autosensitization’ spread. Activation by ultraviolet (UV) radiation of a topical agent, e.g. UV sunscreen filters or previously some perfumes, produces a photocontact reaction in sun-exposed sites (p. 46).

| Allergen | Source |

|---|---|

| Chromate | Cement, tanned leather, primer paint, anticorrosives |

| Cobalt | Pigment, paint, ink, metal alloys |

| Colophonium | Glue, plasticizer, adhesive tape, varnish, polish |

| Epoxy resins | Adhesive plastics, mouldings |

| Fragrances | Cosmetics, creams, soaps, deodorants, aromatherapy |

| Nickel | Jewellery, zips, fasteners, scissors, instruments |

| Paraphenylenediamine | Dye (clothing, hair), shoes, colour developer |

| Plants | Primula obconica, chrysanthemums, garlic, poison ivy/oak (USA) |

| Preservatives | Cosmetics, creams and oils |

| Rubber chemicals | Gloves, clothing, shoes, masks, tyres, condoms |

Differential diagnosis

Contact dermatitis of the hands needs to be differentiated from endogenous eczema, latex contact urticaria (p. 124), psoriasis and fungal infection. Acute contact dermatitis of the face may resemble angioedema or erysipelas.

Management

The management of contact dermatitis is not always easy because of the many and often overlapping factors that can be involved in any one case. The identification of any offending allergen or irritant is the overriding objective. Patch testing (p. 126) helps to identify any allergens involved and is particularly useful in dermatitis of the face, hands and feet. The exclusion of an offending allergen from the environment is desirable and, if this can be achieved, the dermatitis may clear.

Contact dermatitis

Irritant factors of various types cause more contact dermatitis than allergens.

Irritant factors of various types cause more contact dermatitis than allergens.

Irritant contact dermatitis, in many cases, can be difficult to distinguish from allergic or endogenous eczema on morphological grounds alone.

Irritant contact dermatitis, in many cases, can be difficult to distinguish from allergic or endogenous eczema on morphological grounds alone.

Atopics and those with ‘a sensitive skin’ are more susceptible to the effects of irritants.

Atopics and those with ‘a sensitive skin’ are more susceptible to the effects of irritants.

Patch testing is helpful to confirm allergic contact dermatitis, particularly of the face, hands and feet. Specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E tests or prick tests may also be needed, e.g. for latex.

Patch testing is helpful to confirm allergic contact dermatitis, particularly of the face, hands and feet. Specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E tests or prick tests may also be needed, e.g. for latex.

Common allergens: nickel, rubber chemicals, fragrances, chromate, cobalt, colophonium, preservatives, plant allergens and paraphenylenediamine.

Common allergens: nickel, rubber chemicals, fragrances, chromate, cobalt, colophonium, preservatives, plant allergens and paraphenylenediamine.

Common irritants: water, frictional abrasives, chemicals (especially alkalis), solvents, oils, detergents, soaps, low humidity and temperature extremes.

Common irritants: water, frictional abrasives, chemicals (especially alkalis), solvents, oils, detergents, soaps, low humidity and temperature extremes.

Elimination and avoidance of allergens and irritants are useful, although prevention is the ideal.

Elimination and avoidance of allergens and irritants are useful, although prevention is the ideal.