Eczema – Atopic eczema

Definition

Atopic eczema is predominantly a disease of childhood that gives rise to poorly demarcated chronic pruritic papular inflammation of the skin. Uncontrollable scratching is prominent. Most cases improve with age, although approximately 50% of children retain evidence of the condition into adult life. For diagnostic criteria, see Table 1.

(Adapted from Williams et al Br J Dermatol 1994; 131 (3): 406–416).

Aetiopathogenesis

Immunology

Individuals with atopic eczema make aberrant immune responses to environmental allergens which become skewed towards Th2 responses (p. 10), inducing allergen-specific IgE production. The basic cause of these immune defects is still unclear. However, the serum IgE is normal in 20% of atopic eczema subjects.

Clinical presentation

The appearance of atopic eczema differs depending on the age of the patient.

Infancy

Babies develop an itchy vesicular exudative eczema on the face (Fig. 1), head and hands, often with secondary infection. About half continue to have eczema beyond 18 months.

Childhood

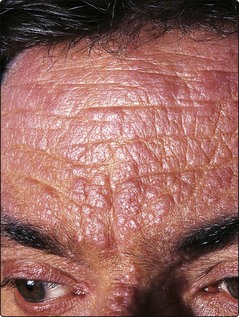

After 18 months, the pattern often changes to the familiar involvement of the flexures (antecubital and popliteal fossae, neck, wrists and ankles) (Figs 2 and 3). The face often shows erythema and infraorbital folds. Lichenification, excoriations and dry skin (Fig. 4) are common, and palmar markings may be increased. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs in those with dark skin. Scratching and rubbing cause most of the clinical signs and are a particular problem at night when they can interfere with sleep. Behavioural difficulties can occur, and a child’s eczema can disrupt family life. Occasionally, a ‘reverse pattern’ of eczema is seen, with involvement of the extensor aspects of the knees and elbows.

Adults

The commonest manifestation in adult life is hand dermatitis, exacerbated by irritants, in someone with a past history of atopic eczema. However, a small number of adults have a chronic severe form of generalized and lichenified atopic eczema (Fig. 5), which may interfere with their employment and social activities. Stressful situations, such as examinations or marital problems, often coincide with exacerbations.

Differential diagnosis

Infantile seborrhoeic eczema (p. 116) may sometimes develop into the atopic variety and, occasionally, the distinction from scabies is necessary. Rarely, infants with immune deficiency syndromes (e.g. Wiskott–Aldrich) or with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (p. 116) have an eczematous eruption.

Complications

Atopic eczema is subject to several complications – some common and some rare:

Bacterial infection. Most individuals with atopic eczema are colonized with Staphylococcus aureus (p. 49) and invasive infection is a common cause of disease exacerbations.

Bacterial infection. Most individuals with atopic eczema are colonized with Staphylococcus aureus (p. 49) and invasive infection is a common cause of disease exacerbations.

Viral infection. Patients have an increased susceptibility to infection with molluscum contagiosum and possibly with viral warts.

Viral infection. Patients have an increased susceptibility to infection with molluscum contagiosum and possibly with viral warts.

Eczema herpeticum. There is a propensity to develop widespread lesions with herpes simplex (Fig. 6).

Eczema herpeticum. There is a propensity to develop widespread lesions with herpes simplex (Fig. 6).

Cataracts. A specific form of cataract infrequently develops in young adults with severe atopic eczema.

Cataracts. A specific form of cataract infrequently develops in young adults with severe atopic eczema.

Growth retardation. Children with severe atopic eczema may have short stature. Topical steroid therapy is unlikely to be causal.

Growth retardation. Children with severe atopic eczema may have short stature. Topical steroid therapy is unlikely to be causal.

Management

General measures include explaining the disorder and its treatment to the patient and the parents, stressing the normally good prognosis. Nails should be kept short. The exclusion of house dust mite from the home environment is difficult. Careers advice to avoid wet work jobs (e.g. nursing, hairdressing, cleaning) and those with exposure to irritant oils is important. Some sufferers obtain support from groups such as the National Eczema Society (p. 132).

Specific treatments for atopic eczema are summarized in Table 2.

| Treatment | Indication |

|---|---|

| Emollients | Most eczema; ichthyosis |

| Topical steroids | Most types of eczema |

| Topical tacrolimus | Steroid-resistant eczema |

| Tar bandage | Lichenified/excoriated eczema |

| Oral antihistamine | Pruritus |

| Oral antibiotic | Bacterial superinfection |

| Exclusion diet | Food allergy/resistant eczema |

| UVB, ciclosporin and azathioprine | Resistant and severe eczema unresponsive to topical therapy |

Topical therapy

Washing and emollient therapy

Soap and ‘bubbly’ products should be completely avoided. Emollients (p. 22) should be used regularly on the skin and to wash with. They moisturize the dry skin, diminishing the desire to scratch and reducing the need for topical steroids. The greasy emollients (ointments) are more effective at repairing the skin barrier and therefore are usually more effective. Creams containing antiseptics such as chlorhexidine and bath oils may also help.

Systemic therapy

Sedative antihistamines, given at night, are helpful principally through the sedative effect. Infected exacerbations frequently require the intermittent use of an oral antistaphylococcal antibiotic. Eczema herpeticum should be assessed urgently and treated with aciclovir. Patients with severe and resistant forms of atopic eczema may be treated with narrow-band UVB (p. 106), azathioprine or ciclosporin (p. 23).

Dietary manipulation

Atopic eczema

Affects 20–30% of UK infants: onset at less than 1 year in 60% of cases.

Affects 20–30% of UK infants: onset at less than 1 year in 60% of cases.

Loss of skin barrier function including filaggrin mutations is central to the disease pathogenesis.

Loss of skin barrier function including filaggrin mutations is central to the disease pathogenesis.

Classically affects the face in infants, later knee and elbow flexures.

Classically affects the face in infants, later knee and elbow flexures.

Itch–scratch cycle induces lichenification.

Itch–scratch cycle induces lichenification.

Exacerbations are often due to infection, particularly staphylococcal.

Exacerbations are often due to infection, particularly staphylococcal.

Treatment involves emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, clothing, systemic antihistamines and antibiotics.

Treatment involves emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, clothing, systemic antihistamines and antibiotics.