Chapter 24 Ectopic Pregnancy

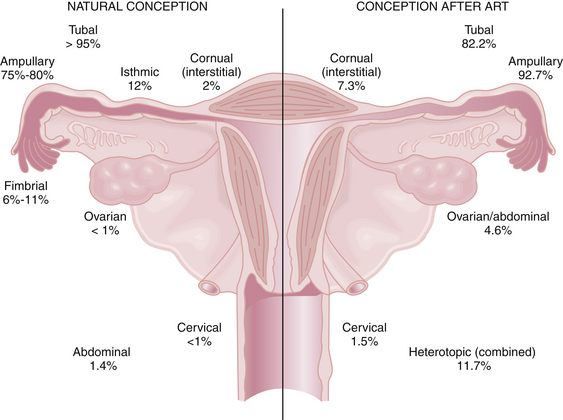

An ectopic pregnancy is a gestation that implants outside the endometrial cavity. Despite recent advances in earlier detection, it continues to represent a serious hazard to women’s health and their future reproductive potential. An ectopic pregnancy is estimated to occur in 1 of every 80 spontaneously conceived pregnancies. More than 95% of ectopic pregnancies implant in various anatomic segments of the fallopian tube, including the ampullary (75% to 80%), isthmic (12%), infundibular and fimbrial (6% to 11%), and interstitial (2%). Other, less common sites of ectopic implantation are the ovary, uterine cervix, and a rudimentary uterine horn. Rarely, an ectopic pregnancy may be intraligamentous or in the peritoneal cavity (abdominal pregnancy). With in vitro fertilization (IVF) and other assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), the risk for ectopic pregnancy increases substantially, and the location of those ectopic implantations changes (Figure 24-1). Importantly, the risk for heterotropic implantations (one intrauterine and one ectopic) may rise to 1 in 100 with IVF. Other risk factors for an ectopic pregnancy include a history of a previous ectopic pregnancy, a pregnancy after tubal ligation or with an intrauterine device (IUD) in place, and a history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Epidemiology and Etiology

Epidemiology and Etiology

The etiology of ectopic pregnancy is not always clear but often is associated with known risk factors (Box 24-1). As many as half of cases result from an alteration of tubal transport mechanisms because of damage to the ciliated surface of the endosalpinx caused by infections, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea. Other etiologies include delayed fertilization, possible transmigration of the oocyte to the contralateral tube, and slowed tubal transport, which delays passage of the morula to the endometrial cavity. Chromosomal abnormalities of the fetus are not a cause of ectopic pregnancy.

Symptoms and Clinical Diagnosis of Ectopic Tubal Pregnancy

Symptoms and Clinical Diagnosis of Ectopic Tubal Pregnancy

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

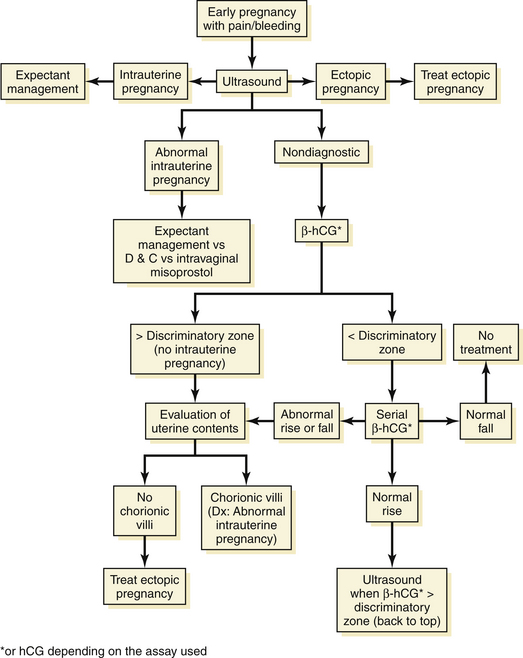

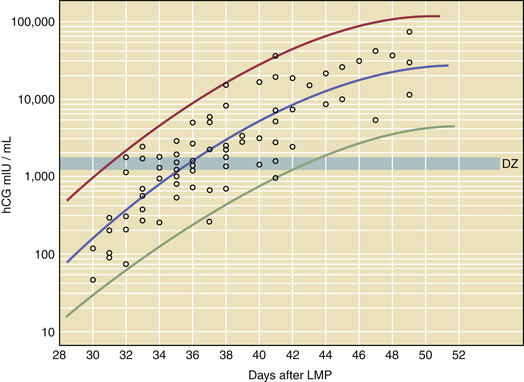

Additional tests are often needed to assist in the diagnosis if the patterns in serial hCGs do not give complete results. Transvaginal ultrasound is helpful in diagnosing an ectopic pregnancy by failure to identify an IUP after the hCG levels are adequately high. Although some IUPs may be seen at lower hCG levels, every IUP should be visualized by the time the hCG levels reach the so-called discriminatory zone. The discriminatory zone, or DZ, is defined as the titer of hCG at which an intrauterine sac should reliably be seen with transvaginal ultrasonography in a normal pregnancy. DZ titers differ among institutions, but on average are equal to 1500 to 2000 mIU/mL of hCG for a singleton pregnancy and 3000 mIU/mL for a twin gestation (Figure 24-3).

Management

Management

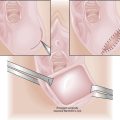

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

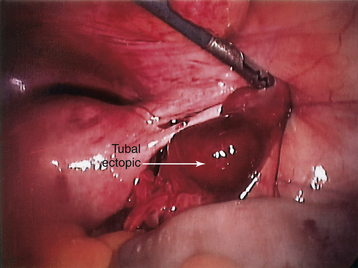

Laparotomy is the preferred surgical approach for women who are hemodynamically unstable because rapid access to the bleeding site is critical. Laparotomy is also appropriate whenever it is anticipated that laparoscopy would not be successful, such as when the patient has significant intraperitoneal adhesions from prior surgeries, infection, or endometriosis. For hemodynamically stable patients, laparoscopy (when available) is the preferred surgical approach because after laparoscopic surgery, patients require fewer days of postoperative hospitalization, suffer less postoperative pain, and recover more quickly. Laparoscopy also offers the potential to reduce overall treatment costs. If it is determined intraoperatively that laparoscopy is not possible, the surgery can always be converted to laparotomy. Laparoscopy is discussed further in Chapter 30.Figure 24-4 shows a tubal ectopic pregnancy viewed through the laparoscope.

FIGURE 24-4 A tubal ectopic pregnancy as seen through the laparoscope.

(Courtesy of B. Beller, MD, Eugene, Oregon.)

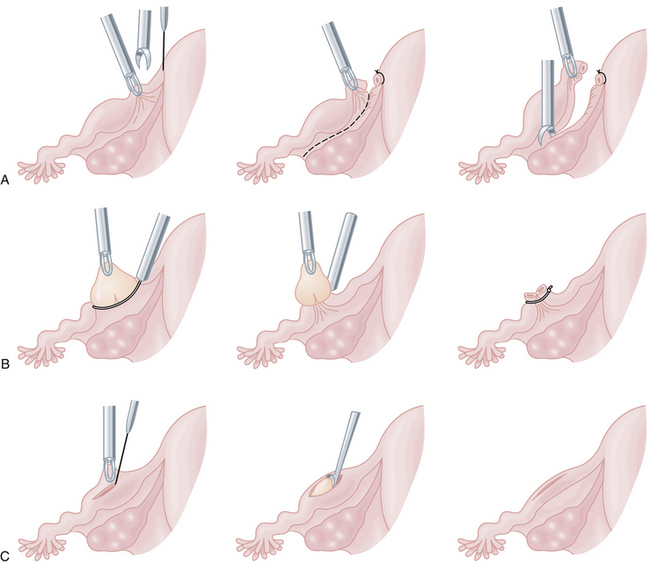

Salpingectomy (removal of the entire fallopian tube) is recommended when there has been significant damage to the tube, when removal of the damaged elements would leave in place less than 6 cm of functional tube, or when a patient who previously has been sterilized verifies that she still does not desire future fertility. Figure 24-5A illustrates a laparoscopic salpingectomy. Partial salpingectomy (removal of a portion of the fallopian tube) is generally performed only if the ectopic pregnancy is implanted in the mid-ampullary portion. The remnants of the tube may be reapproximated in the future. Figure 24-5B illustrates a laparoscopic Endoloop partial salpingectomy. Salpingotomy and salpingostomy are both procedures in which the ectopic pregnancy site is identified and vasoconstrictive agents are injected beneath the implantation site prior to an incision. With salpingotomy, the incision is closed, whereas it is left open in salpingostomy. An incision is made parallel to the axis of the tube along its antimesenteric border over the site of implantation. The products of conception are removed by gentle dissection or hydrodissection (the use of injected fluid to separate tissues). Bleeding is controlled by judicious use of electrocoagulation. The tube and pelvis are copiously irrigated. Figure 24-5C illustrates a laparoscopic linear salpingostomy. Most studies have shown that salpingostomy (incision left open), compared with salpingotomy, results in better long-term tubal function.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT WITH METHOTREXATE

Ambulatory diagnosis and management of women with early, unruptured ectopic pregnancies has replaced surgical diagnosis and treatment in most cases. The most commonly used agent is MTX, which is a folic acid antagonist that inhibits DNA synthesis and cell reproduction. Because of the side effects of MTX and the potential for tubal rupture, careful guidelines for patient selection are required, as shown in Box 24-3.

BOX 24-3 Criteria for Medical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy with Methotrexate

Data from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): Medical management of tubal pregnancy. Practice Bulletin No. 3. Washington, DC, ACOG, December 1998.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee. Revised Practice Committee report on medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(Suppl 1):S96-S102.

Hajenius P.J., Mol F., Mol B.W., et al. Interventions for ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2007. CD000324

Lipscomb G.H. Medical therapy for ectopic pregnancy. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:93-98.

Menon S., Colins J., Barnhart K.T., et al. Establishing a human chorionic gonadotropin cutoff to guide methotrexate treatment of ectopic pregnancy: A systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:481-484.

Seeber B.E., Barnhart K.T. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):399-413.

Natural History of Untreated Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy

Natural History of Untreated Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy

Treatment of Uncommon Types of Ectopic Pregnancies

Treatment of Uncommon Types of Ectopic Pregnancies Implications for Future Fertility

Implications for Future Fertility