32 Ectopia Cordis

Anatomy and Anatomical Associations

Ectopia cordis is a rare but very dramatic congenital malformation in which the heart is located outside of the confines of the chest cavity.1–3 The condition can be classified into four types, depending upon the position of the heart: cervical, thoracic, thoracoabdominal, or abdominal. The most common type is thoracic ectopia in which the heart lies partially or completely outside the chest wall with the ventricular apex pointing cephalad.

Ectopia cordis is commonly associated with other anomalies including intracardiac defects and other “midline” body wall defects. In 1958, Cantrell and coworkers4 described a “pentalogy” of five associated findings including a midline supraumbilical abdominal wall defect, a defect of the lower part of the sternum, a deficiency of the anterior diaphragm, a pericardial defect at the diaphragmatic surface, and a congenital heart malformation. In this syndrome, the heart disease is often a ventricular septal defect or a conotruncal anomaly such as tetralogy of Fallot or double-outlet right ventricle. Diverticulum of the left ventricle apex is also associated, seen in approximately 20% of cases.

Although Cantrell and coworkers described their particular findings as a constellation, in fact patients may have any one of these alone or a wide spectrum of additional anomalies in association with ectopia cordis. These include abdominal wall defects such as omphalocele, diastasis recti, or gastroschisis as well as craniofacial defects such as cleft lip/palate or neural tube defects. Cases of so-called partial pentalogy of Cantrell have been described, in which there is no sternal defect, but rather a large omphalocele with the heart protruding in a thoracoabdominal manner.5 Hence, two mechanisms for evisceration of the heart outside of the chest wall have been proposed. One is a defect in the sternum with direct protrusion through, referred to as thoracoschisis. The other is a reverse diaphragmatic hernia in which there is a defect in the diaphragm with the heart protruding into the abdomen in association with an omphalocele within which the abdominal contents including the heart is outside of the body.6 The embryological mechanisms for these two may be different.

Frequency, Genetics, and Development

Ectopia cordis makes up less than 0.1% of all congenital heart defects. Failure of fusion of the paired cartilage bars of the embryonic sternum leads to a sternal cleft (thoracoschisis), which allows for the potential for the heart to be positioned outside the boundaries of the chest wall. The incidence ranges from 5.5 to 7.9 per 1 million live births. Two thirds of patients are male; one third are born premature or stillborn. Ectopia cordis is part of a developmental field complex defect, which involves deficiency in formation of the sternum, diaphragm, and anterior body wall. A familial pattern has been reported.7 Ectopia cordis can be associated with a number of genetic and chromosomal anomalies including trisomy 188 and can be experimentally induced in animals through a variety of teratogens.9,10

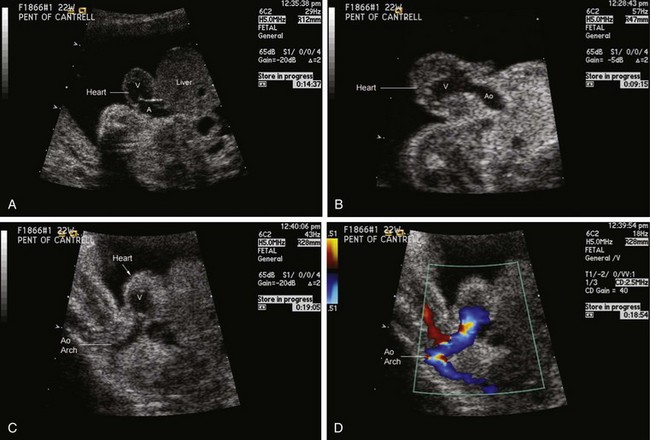

Prenatal Management

Careful evaluation of the cardiac position, the amount of heart sitting outside of the chest, the precise type of congenital heart disease, and other associated anomalies is important. Karyotype evaluation is indicated. Oftentimes, suspicion is first raised by the presence of abnormal elevation in first-trimester serum markers, which then leads to early detailed imaging. Ectopia cordis can be diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy, as early as 10 weeks’ gestation.11,12 Partial protrusion of the heart outside of the chest wall as an isolated finding is unusual, and there are commonly many other associated anomalies. Figuring out the anatomy at the junction of the chest, abdomen, and diaphragm can be a challenge. Fetal echocardiography can be complemented by the use of fetal magnetic resonance imaging to obtain a more precise sense of the anatomy with particular focus on the relationship of the heart to the sternum, diaphragm, and abdominal wall defect.13,14 Considering the poor prognosis in most cases, detailed evaluation and counseling are important as early as possible.

Postnatal Management and Outcomes

Overall prognosis for ectopia cordis is extremely poor with less than 5% survival beyond the neonatal period.1 There are case reports of neonatal surgery, with survival very much dependent upon additional associated anomalies.2 The presence of pulmonary hypoplasia is uniformly fatal. Cervical ectopia cordis has extremely poor prognosis, because kinking of vessels and constriction of the heart occur with attempts at repositioning of the heart at surgery.

For thoracic ectopia cordis with associated congenital heart disease, but no other significant extracardiac anomalies, surgical repair can be attempted with some success.3 The principles of surgical treatment for this disease are to (1) provide soft tissue cover of the heart, (2) reduce the heart into the thoracic cavity, (3) palliate or repair any intracardiac defect, and (4) reconstruct the chest wall. These goals can be achieved in a thoughtful staged manner, in some instances.15 Single-ventricle palliation has been successfully undertaken in patients with well-formed lungs and no other major anomalies.16,17 Long-term outcome beyond a few years of age has not been reported.

1 Amato JJ, Douglas WI, Desai U, Burke S. Ectopia cordis. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2000;10:297-316. vii

2 Morales JM, Patel SG, Duff JA, Villareal RL, Simpson JW. Ectopia cordis and other midline defects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:111-114.

3 Hornberger LK, Colan SD, Lock JE, Wessel DL, Mayer JEJr. Outcome of patients with ectopia cordis and significant intracardiac defects. Circulation. 1996;94:II32-II37.

4 Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:602-614.

5 van Hoorn JH, Moonen RM, Huysentruyt CJ, van Heurn LW, Offermans JP, Mulder AL. Pentalogy of Cantrell: two patients and a review to determine prognostic factors for optimal approach. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:29-35.

6 Davies BR, Duran M. The confused identity of Cantrell’s pentad: ectopia cordis is related either to thoracoschisis or to a diaphragmatic hernia with an omphalocele. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med. 2003;22:383-390.

7 Martin RA, Cunniff C, Erickson L, Jones KL. Pentalogy of Cantrell and ectopia cordis, a familial developmental field complex. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:839-841.

8 Shaw SW, Cheng PJ, Chueh HY, Chang SD, Soong YK. Ectopia cordis in a fetus with trisomy 18. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:95-98.

9 Ejaz S, Ejaz A, Sohail A, Ahmed M, Nasir A, Lim CW. Exposure of smoke solutions from CNG-powered four-stroke auto-rickshaws induces distressed embryonic movements, embryonic hemorrhaging and ectopia cordis. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:1442-1452.

10 Ejaz S, Ashraf M, Nawaz M, Lim CW, Kim B. Anti-angiogenic and teratological activities associated with exposure to total particulate matter from commercial cigarettes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:368-376.

11 Liang RI, Huang SE, Chang FM. Prenatal diagnosis of ectopia cordis at 10 weeks of gestation using two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10:137-139.

12 Barbee K, Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A, Blackstone J. First-trimester prenatal sonographic diagnosis of ectopia cordis in a twin gestation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37:539-540.

13 McMahon CJ, Taylor MD, Cassady CI, Olutoye OO, Bezold LI. Diagnosis of pentalogy of cantrell in the fetus using magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Pediatr Cardiol. 2007;28:172-175.

14 Moniotte S, Powell AJ, Barnewolt CE, Annese D, Geva T. Prenatal diagnosis of thoracic ectopia cordis by real-time fetal cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and by echocardiography. Congenit Heart Dis. 2008;3:128-131.

15 Alphonso N, Venu PS, Deshpande R, Anderson D. Complete thoracic ectopia cordis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:426-428.

16 Tokunaga S, Kado H, Imoto Y, Shiokawa Y, Yasui H. Successful staged-Fontan operation in a patient with ectopia cordis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:715-717.

17 Okamoto Y, Harada Y, Uchita S. Fontan operation through a right lateral thoracotomy to treat Cantrell syndrome with severe ectopia cordis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:278-279.