26 Echocardiographic Guidance of Procedures

Jugular Venous Cannulation

Sequence

Place the patient in Trendelenburg position to increase the size of the neck veins.

Place the patient in Trendelenburg position to increase the size of the neck veins.

With the skin cleaned and sterile, introduce the probe into a sterile plastic sheath.

With the skin cleaned and sterile, introduce the probe into a sterile plastic sheath.

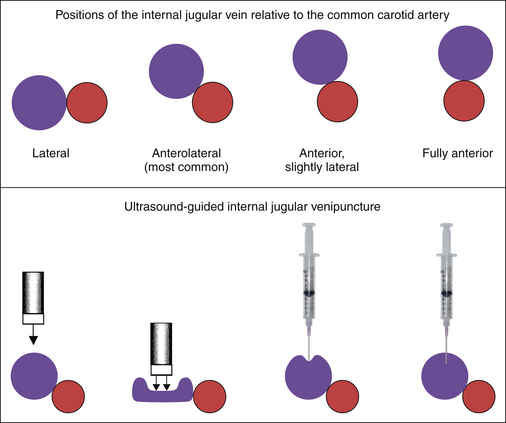

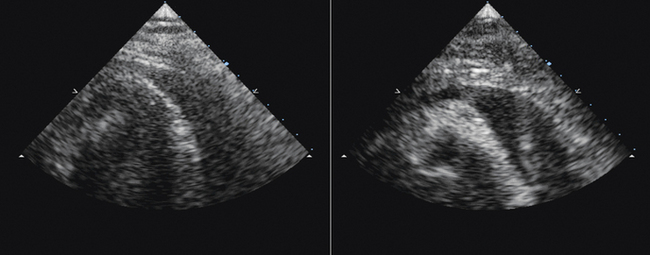

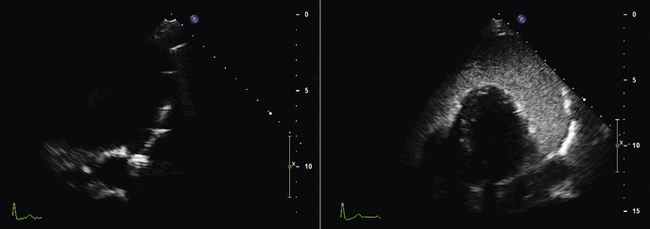

Image from the anterior neck in the mid-portion, which overlies the internal jugular vein and the common carotid artery. The jugular vein, depending on the central venous pressure, may be (usually is) larger than the common carotid artery, but in volume-contracted or dehydrated patients, the vein may be smaller than the artery. The vein may lie to the side of, anterolateral to (this is its usual location in the mid-neck), anterior but slightly lateral to, or completely anterior to the artery.

Image from the anterior neck in the mid-portion, which overlies the internal jugular vein and the common carotid artery. The jugular vein, depending on the central venous pressure, may be (usually is) larger than the common carotid artery, but in volume-contracted or dehydrated patients, the vein may be smaller than the artery. The vein may lie to the side of, anterolateral to (this is its usual location in the mid-neck), anterior but slightly lateral to, or completely anterior to the artery.

The most desirable site for cannulation is where the vein is substantially at least lateral to the artery, so that inadvertent transfixion of the vein runs little risk of inadvertently puncturing the common carotid artery. Avoid locations where the jugular vein is directly anterior to the artery.

The most desirable site for cannulation is where the vein is substantially at least lateral to the artery, so that inadvertent transfixion of the vein runs little risk of inadvertently puncturing the common carotid artery. Avoid locations where the jugular vein is directly anterior to the artery.

The vein is identified by the following:

The vein is identified by the following:

If the vein is generously full, the needle is inserted carefully through the taut anterior wall of the vein until the tip is a few millimeters into the lumen.

If the vein is generously full, the needle is inserted carefully through the taut anterior wall of the vein until the tip is a few millimeters into the lumen.

If the vein is full but limp, have the patient make a partial Valsalva maneuver to distend the vein, providing a larger target for the needle puncture and a more taut anterior wall.

If the vein is full but limp, have the patient make a partial Valsalva maneuver to distend the vein, providing a larger target for the needle puncture and a more taut anterior wall.

It is easiest if the patient is told to take a breath (inspire) before he or she is told to strain (perform a Valsalva maneuver). Guiding the patient in practicing the performance of a Valsalva maneuver before the procedure is helpful for patients who are not familiar with it.

It is easiest if the patient is told to take a breath (inspire) before he or she is told to strain (perform a Valsalva maneuver). Guiding the patient in practicing the performance of a Valsalva maneuver before the procedure is helpful for patients who are not familiar with it.

Visualize the wire extending from the needle.

Visualize the wire extending from the needle.

Visualize the sheath within the lumen following its insertion.

Visualize the sheath within the lumen following its insertion.

Be aware of the presence of jugular venous valves, a normal aspect of anatomy. Insertion beneath the valves may simplify the procedure.

Be aware of the presence of jugular venous valves, a normal aspect of anatomy. Insertion beneath the valves may simplify the procedure.

Be aware of the appearance of jugular venous thrombus, a common residua of prior catheter and wire insertions

Be aware of the appearance of jugular venous thrombus, a common residua of prior catheter and wire insertions

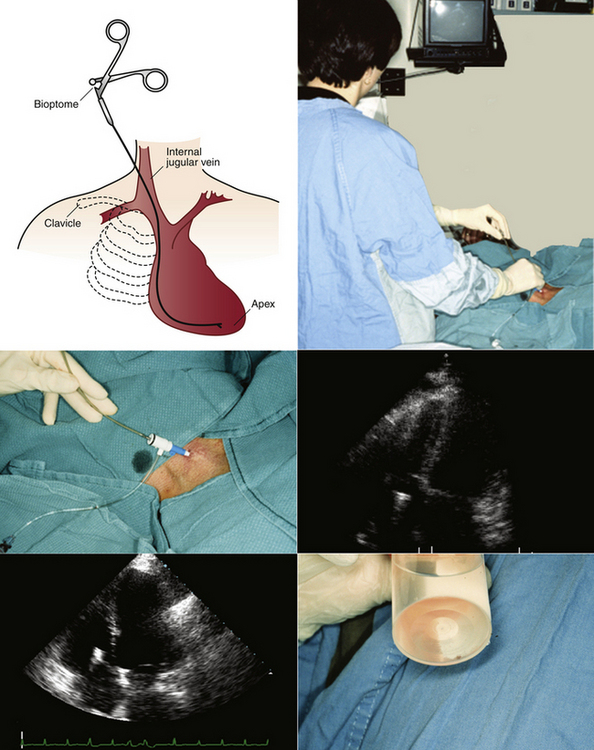

Endomyocardial Biopsy

To reliably diagnose heart transplant rejection, right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy (percutaneous procurement of endomyocardial samples from the right ventricle1,2) remains the gold standard. Right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy also is a valuable way to assist with diagnosis and management of suspected myocarditis, infiltrative cardiomyopathy, or other unexplained ventricular dysfunction.

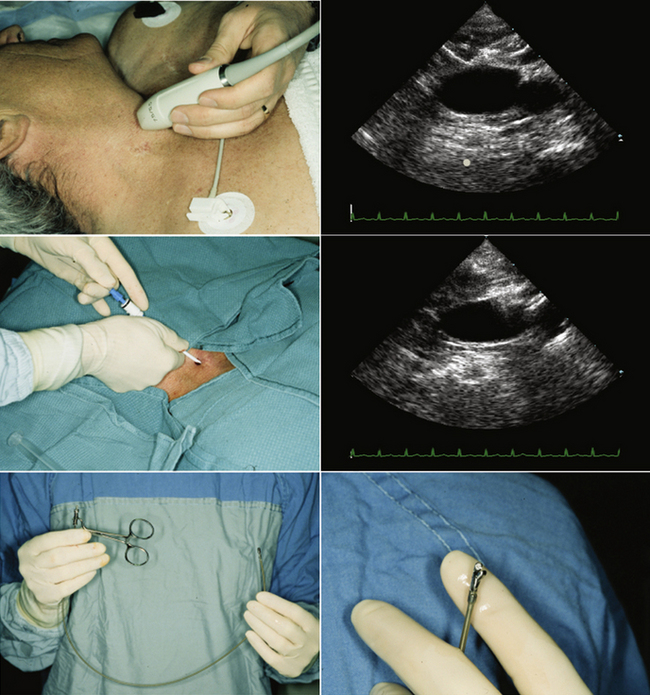

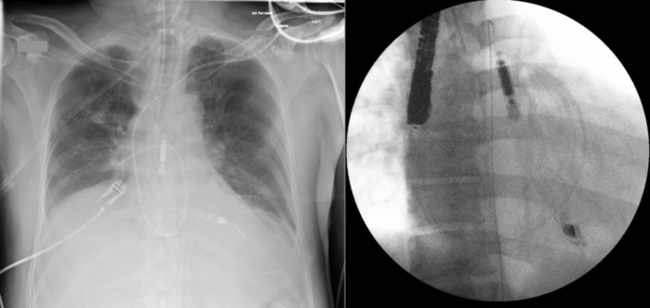

Percutaneous right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy most commonly is performed using cannulation of the right internal jugular vein. In circumstances where this vessel is not usable, the femoral vein can be used for this purpose. Cardiologists traditionally have relied on fluoroscopic guidance for placement of the bioptome. Using frontal-plane fluoroscopic guidance, the bioptome is directed toward the right ventricular septum to obtain right ventricular samples. Bioptome contact with the right ventricular septum is confirmed by the presence of ventricular ectopic beats, and samples are taken from that site. Typically at least four biopsy samples are obtained, because a minimum of three adequate biopsy samples are required for histologic diagnosis. The use of fluoroscopy to guide right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy has a number of drawbacks: it provides only approximate bioptome placement information; exposes both the patient and physician to radiation; and requires use of the cardiac catheterization laboratory—a facility in high demand. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the complication rate ranges from 6% to 14%,3,4 with possible complications including myocardial perforation, tricuspid valve apparatus disruption, arrhythmias, coronary artery to right ventricular fistula, and inadvertent arterial punctures. A significant limitation of fluoroscopic guidance for right ventricular endomyocardial biopsies is that the bioptome placement and subsequent sampling area are limited due to inability to place the bioptome precisely, leading to repeated sampling from the same area. This contributes to biopsies that consist predominantly of scar from previous biopsy sites, which are inadequate for histologic assessment, and to reduced sensitivity due to the potentially focal nature of rejection or other cardiac histologic processes.

Sequence

Echocardiographically guided endomyocardial biopsy usually is performed in the echocardiography laboratory, with the assistance of an echosonographer and a nurse.

Echocardiographically guided endomyocardial biopsy usually is performed in the echocardiography laboratory, with the assistance of an echosonographer and a nurse.

The person performing the biopsy procedure stands at the head of the bed, with the echosonographer and echocardiography machine to the patient’s left and the nurse and sterile tray to the patient’s right.

The person performing the biopsy procedure stands at the head of the bed, with the echosonographer and echocardiography machine to the patient’s left and the nurse and sterile tray to the patient’s right.

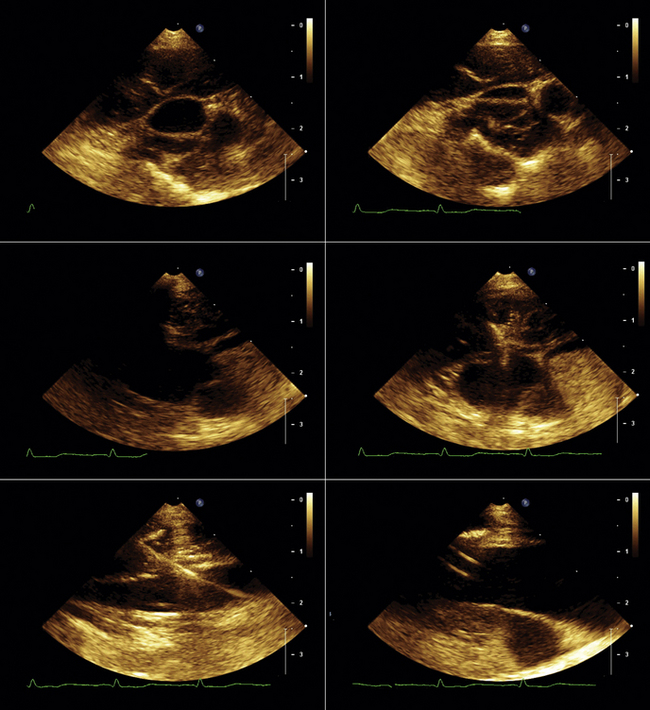

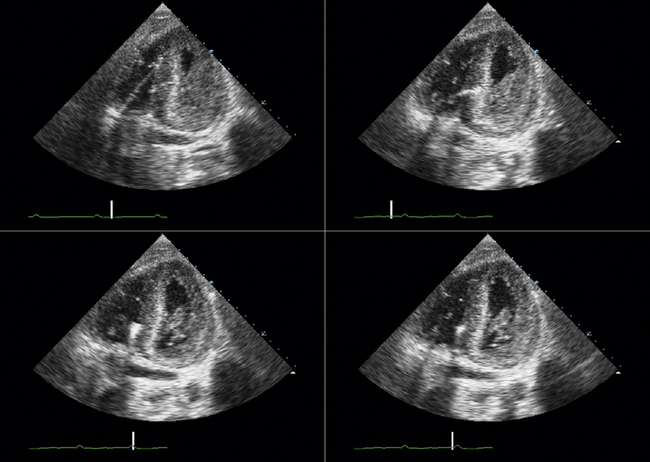

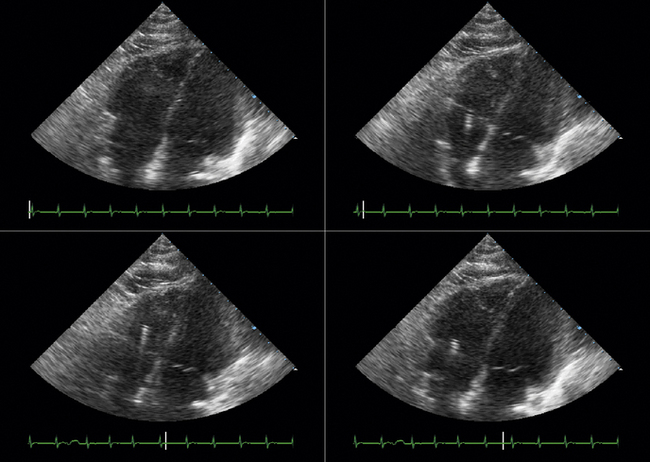

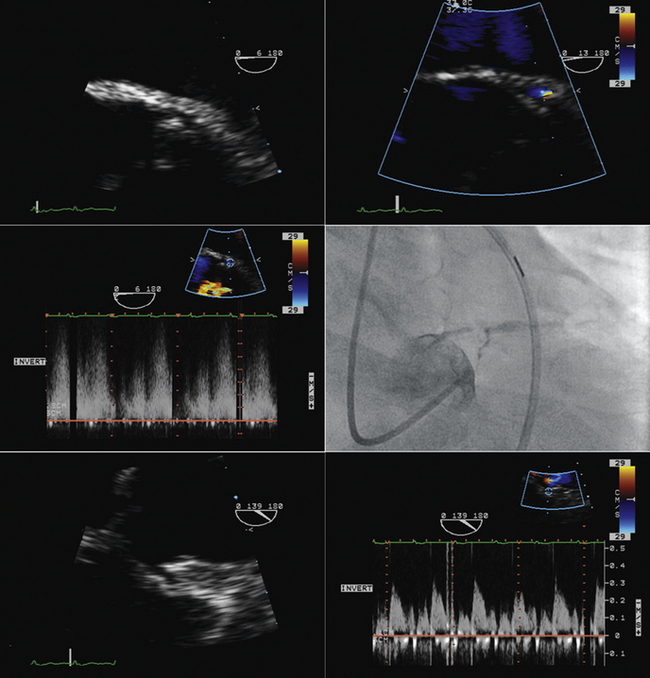

Echocardiographic images are obtained prior to venous cannulation to determine the optimal window and views for visualization of the right atrium and ventricle; to briefly assess left and right ventricular systolic function, the presence and amount of pericardial fluid present, and the presence and degree of tricuspid regurgitation; and to estimate right ventricular systolic pressure. Preprocedure imaging also determines the ideal patient positioning. In many cases supine imaging is adequate, but patients may be moved into the left lateral lying position after initial insertion of the jugular venous sheath to optimize visualization of the right-sided cardiac structures. Ultrasound assessment of the right internal jugular vein may be done at this time, to assist in venous cannulation.

Echocardiographic images are obtained prior to venous cannulation to determine the optimal window and views for visualization of the right atrium and ventricle; to briefly assess left and right ventricular systolic function, the presence and amount of pericardial fluid present, and the presence and degree of tricuspid regurgitation; and to estimate right ventricular systolic pressure. Preprocedure imaging also determines the ideal patient positioning. In many cases supine imaging is adequate, but patients may be moved into the left lateral lying position after initial insertion of the jugular venous sheath to optimize visualization of the right-sided cardiac structures. Ultrasound assessment of the right internal jugular vein may be done at this time, to assist in venous cannulation.

Venous access is obtained using standard Seldinger technique via the right internal jugular vein, with a sheath left in place.

Venous access is obtained using standard Seldinger technique via the right internal jugular vein, with a sheath left in place.

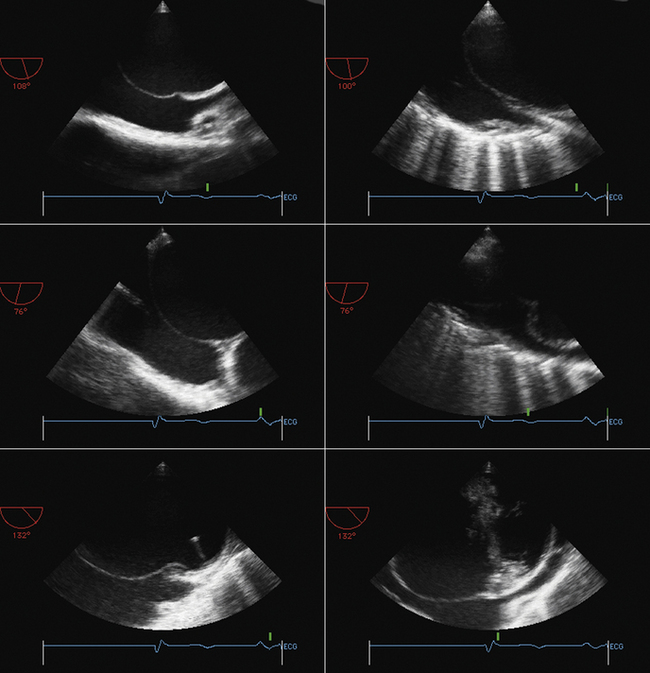

The bioptome is then inserted through the venous sheath into the right atrium.

The bioptome is then inserted through the venous sheath into the right atrium.

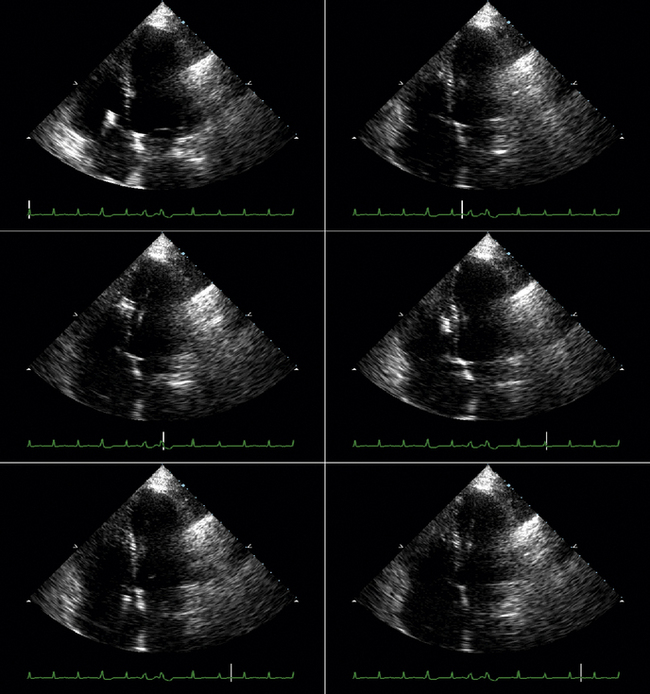

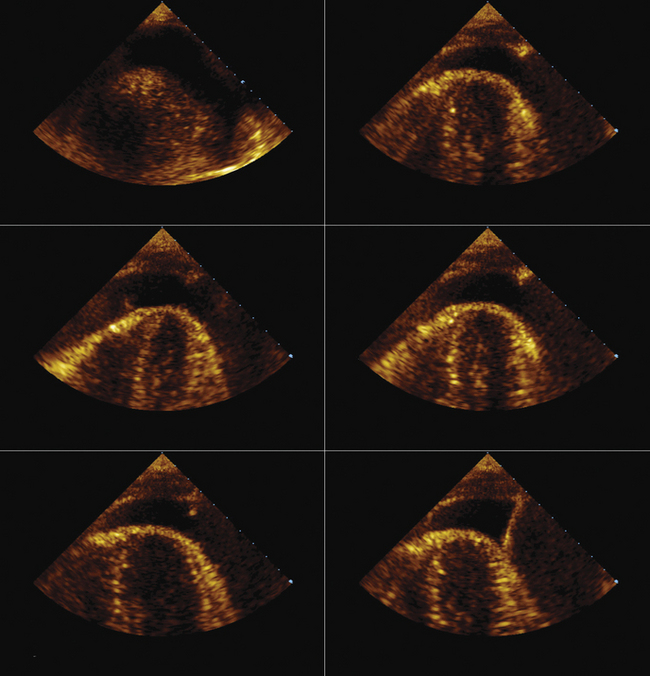

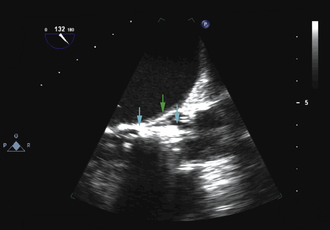

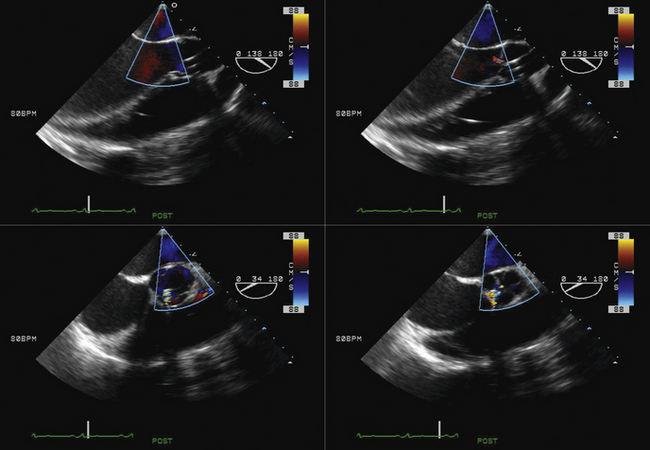

Using echocardiographic imaging to visualize the right-sided chambers and tricuspid valve and apparatus, the bioptome is then passed across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. The endocardial surfaces of the right ventricle are visualized, and the sonographer “follows” the advancement of the bioptome, keeping the forceps head of the bioptome clearly imaged throughout the procedure. The operator maneuvers the bioptome to the desired location, avoiding the moderator band and tricuspid apparatus. Once the bioptome is approximated next to the endomyocardial surface in the desired position, the jaws of the bioptome are opened, and the bioptome is advanced gently against the endomyocardium. Once in place, the jaws are closed and, with a very gentle tug, the biopsy sample is obtained. The bioptome is removed, the sample is placed in sterile saline, and the procedure is repeated until an adequate number of samples have been obtained.

Using echocardiographic imaging to visualize the right-sided chambers and tricuspid valve and apparatus, the bioptome is then passed across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. The endocardial surfaces of the right ventricle are visualized, and the sonographer “follows” the advancement of the bioptome, keeping the forceps head of the bioptome clearly imaged throughout the procedure. The operator maneuvers the bioptome to the desired location, avoiding the moderator band and tricuspid apparatus. Once the bioptome is approximated next to the endomyocardial surface in the desired position, the jaws of the bioptome are opened, and the bioptome is advanced gently against the endomyocardium. Once in place, the jaws are closed and, with a very gentle tug, the biopsy sample is obtained. The bioptome is removed, the sample is placed in sterile saline, and the procedure is repeated until an adequate number of samples have been obtained.

Samples may be taken from the mid to distal right ventricular septum, apex, and free wall in post–cardiac transplant patients, but are usually restricted to the mid- to distal right ventricular septum in non–transplant patients.

Samples may be taken from the mid to distal right ventricular septum, apex, and free wall in post–cardiac transplant patients, but are usually restricted to the mid- to distal right ventricular septum in non–transplant patients.

Post-procedure echocardiographic imaging assesses for changes in the presence or degree of tricuspid regurgitation and/or pericardial fluid.

Post-procedure echocardiographic imaging assesses for changes in the presence or degree of tricuspid regurgitation and/or pericardial fluid.

Two decades ago, Miller published his successful results using echocardiographic guidance for right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy.5 Despite this and other reports of reduced costs and an improved safety profile using echocardiography to guide right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy in adults and children,6–10 this technique has not gained widespread popularity.

Pros

Provision of additional information

Provision of additional information

Despite valid and compelling benefits, there has been reluctance to adopt echocardiographically guided right ventricular biopsy. A typical argument against the technique is the perception that it is difficult to get adequate echocardiographic images in some patients. In 90% of patients, however, the standard apical four-chamber view can be used to view the bioptome head,6 although modifications of this view may be necessary to provide optimal imaging during bioptome manipulation.

Pericardiocentesis

Sequence

Unlike chest CT scan, real-time imaging by echocardiography of the heart’s motion within the pericardial space enables determination of the dimension of pericardial fluid throughout the cardiac cycle, which can vary considerably between diastole and systole.

Unlike chest CT scan, real-time imaging by echocardiography of the heart’s motion within the pericardial space enables determination of the dimension of pericardial fluid throughout the cardiac cycle, which can vary considerably between diastole and systole.

During the procedure, use of a sterile sleeve to enable scanning immediately beside the site of puncture allows for real-time imaging.

During the procedure, use of a sterile sleeve to enable scanning immediately beside the site of puncture allows for real-time imaging.

Transseptal Puncture

Rationale and Role

Visual guidance by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) of interatrial septal puncture to lessen risk of inadvertent puncture complications and identify any complications that do occur

Visual guidance by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) of interatrial septal puncture to lessen risk of inadvertent puncture complications and identify any complications that do occur

Guidance of complex transseptal punctures in cases of kyphosis or scoliosis where the heart orientation (specifically that of the interatrial septum) within an abnormal chest cavity is unclear without imaging

Guidance of complex transseptal punctures in cases of kyphosis or scoliosis where the heart orientation (specifically that of the interatrial septum) within an abnormal chest cavity is unclear without imaging

Sequence

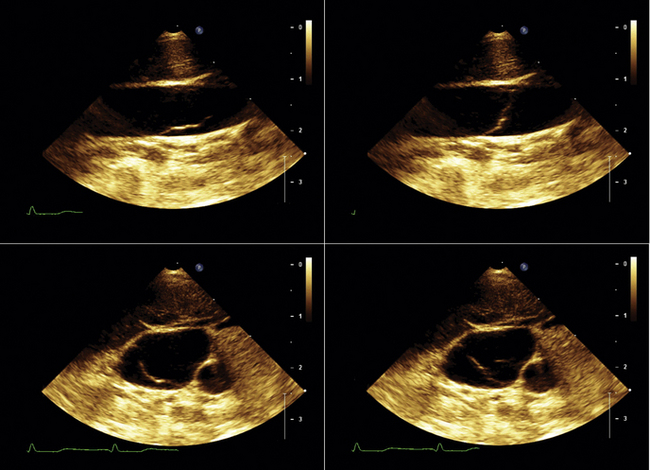

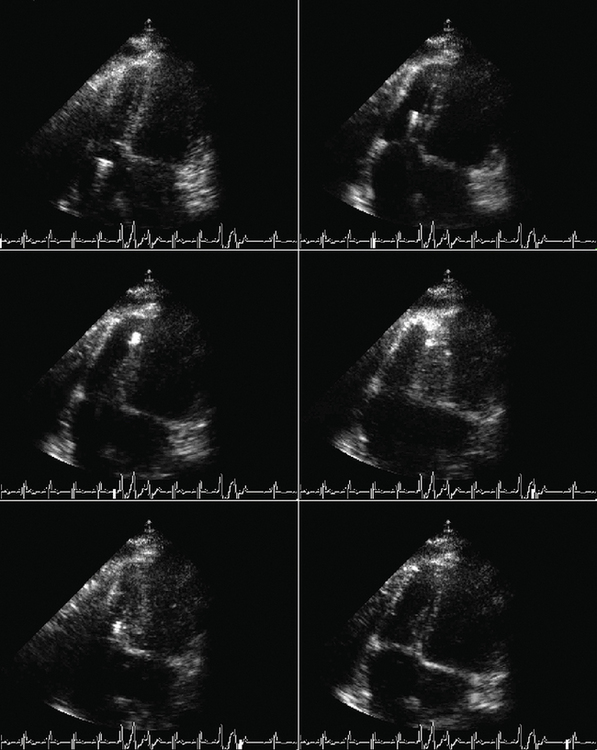

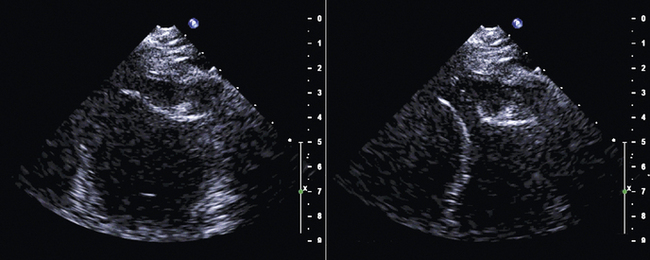

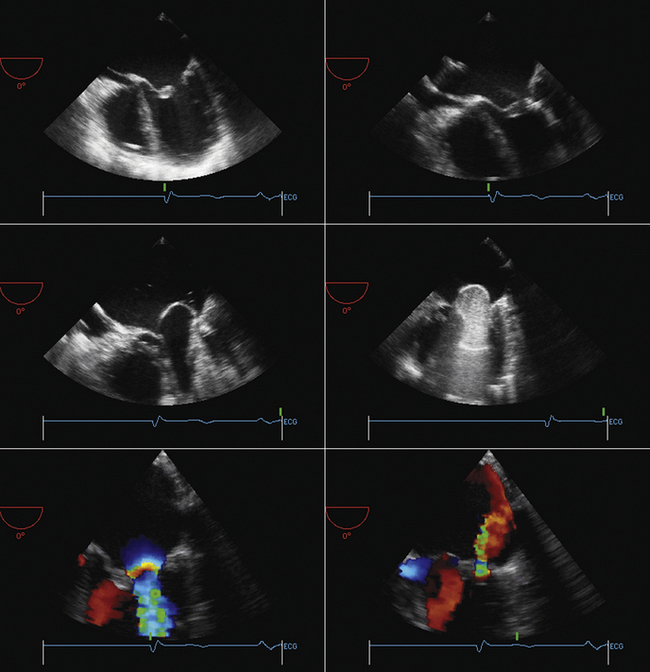

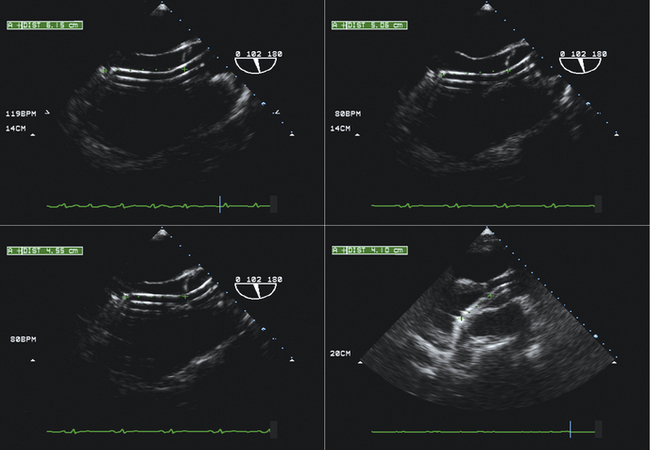

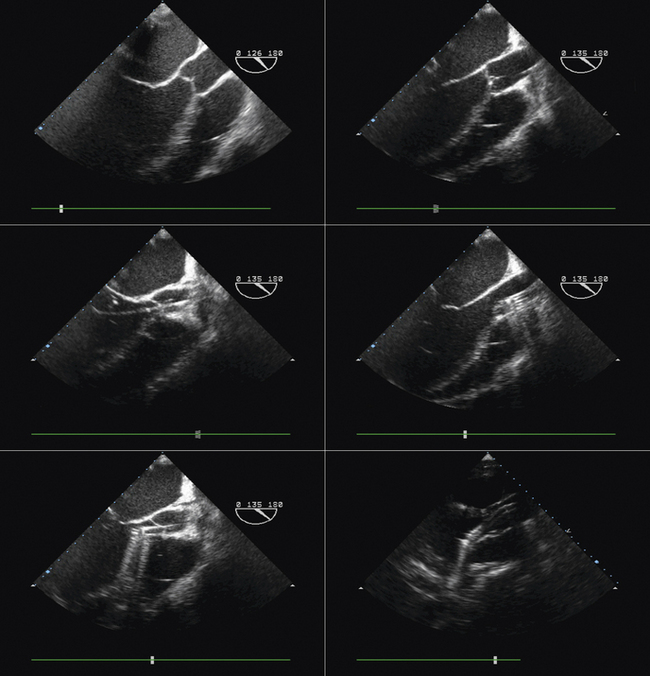

Visualization of the catheter and needle approaching the heart (inferior vena cava/bicaval view)

Visualization of the catheter and needle approaching the heart (inferior vena cava/bicaval view)

Visualization of the needle contacting the interatrial septum away from the margin of the septum

Visualization of the needle contacting the interatrial septum away from the margin of the septum

Visualization of the needle tenting the interatrial septum away from the margin of the septum

Visualization of the needle tenting the interatrial septum away from the margin of the septum

Visualization of the needle/catheter in the left atrium

Visualization of the needle/catheter in the left atrium

Visualization of the catheter flush (small bubbles) in the left atrium

Visualization of the catheter flush (small bubbles) in the left atrium

Catheter Mitral Balloon Valvuloplasty

Percutaneous Aortic Valvuloplasty

Sequence

Preprocedural Assessment

Severity/morphology of aortic stenosis

Routine transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is done to assess for aortic stenosis, including ensuring that the stenosis is valvular and determining, at a minimum, the valve gradient and aortic valve area. (Other values such as the dimensionless index may be helpful in some situations.)

Routine transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is done to assess for aortic stenosis, including ensuring that the stenosis is valvular and determining, at a minimum, the valve gradient and aortic valve area. (Other values such as the dimensionless index may be helpful in some situations.)

TEE may be required to yield accurate root dimensions if TTE is technically difficult. The contribution of gated cardiac CT also should be considered for dimensional measurements

The number of key measurements depends on the PAV used:

For the Edwards-Sapien prosthesis

For the Edwards-Sapien prosthesis

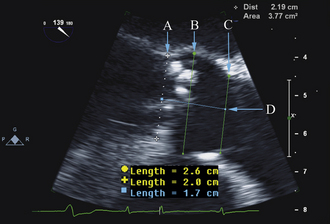

The aortic annulus is a critical measurement in determining patient eligibility and is useful in device sizing. The aortic annulus is not a planar anatomic structure but, rather, a complex 3-dimensional “crown-like” configuration formed by the insertion of the aortic cusps into the aortic wall. Small variations in image plane can produce significantly differing annular measurements. Hence, careful alignment of the aortic root is essential in producing an accurate and reproducible measurement.

Parasternal long-axis view on TTE and the midesophageal long-axis view on TEE

Parasternal long-axis view on TTE and the midesophageal long-axis view on TEE

Measure on a frozen zoomed end-diastolic frame (beginning of the QRS complex after closure of the mitral valve and before opening of the aortic valve).

Measure on a frozen zoomed end-diastolic frame (beginning of the QRS complex after closure of the mitral valve and before opening of the aortic valve).

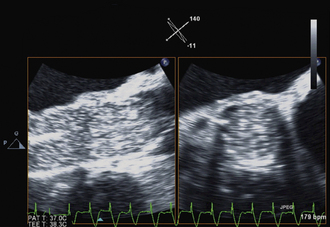

Aortic root walls should be parallel and the aortic valve orifice central in a trileaflet valve. The cross-plane (biplane) feature on three-dimensional probes can be helpful in aligning the aortic root.

Aortic root walls should be parallel and the aortic valve orifice central in a trileaflet valve. The cross-plane (biplane) feature on three-dimensional probes can be helpful in aligning the aortic root.

Measured diameters are intraluminal, from aortic wall to aortic wall, ignoring any protuberant calcium from the measurement.

Measured diameters are intraluminal, from aortic wall to aortic wall, ignoring any protuberant calcium from the measurement.

Annulus diameter is perpendicular to the long axis of the root, measured between the endocardial site that trisects the posterior aortic wall, noncoronary cusp hinge and the anterior mitral leaflet hinge, and the point that bisects the anterior aortic wall and the right coronary cusp hinge.

Annulus diameter is perpendicular to the long axis of the root, measured between the endocardial site that trisects the posterior aortic wall, noncoronary cusp hinge and the anterior mitral leaflet hinge, and the point that bisects the anterior aortic wall and the right coronary cusp hinge.

Our recommendation is to obtain three reproducible measurements:

Aortic valve area–ostial height

Aortic valve area–ostial height

These dimensions are critical for sizing the percutaneous prosthesis.

These dimensions are critical for sizing the percutaneous prosthesis.

Assessment for noncompliant subaortic disease: protuberant calcium in the left ventricular outflow tract, moderate to severe septal hypertrophy

Assessment for noncompliant subaortic disease: protuberant calcium in the left ventricular outflow tract, moderate to severe septal hypertrophy

CoreValve recommends that implantation should not be performed if subaortic disease is sufficient to cause stenosis or if the septal wall thickness is 17 mm or more.

CoreValve recommends that implantation should not be performed if subaortic disease is sufficient to cause stenosis or if the septal wall thickness is 17 mm or more.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with significant left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is a contraindication for both devices.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with significant left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is a contraindication for both devices.

Other valve pathology/cardiac disease

Baseline assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function, regional wall motion abnormalities, right ventricular (RV) function, and pulmonary artery pressure

Baseline assessment of left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function, regional wall motion abnormalities, right ventricular (RV) function, and pulmonary artery pressure

Other test modalities that factor prominently into the preprocedural assessment of percutaneous aortic valve implantation procedures include

Other test modalities that factor prominently into the preprocedural assessment of percutaneous aortic valve implantation procedures include

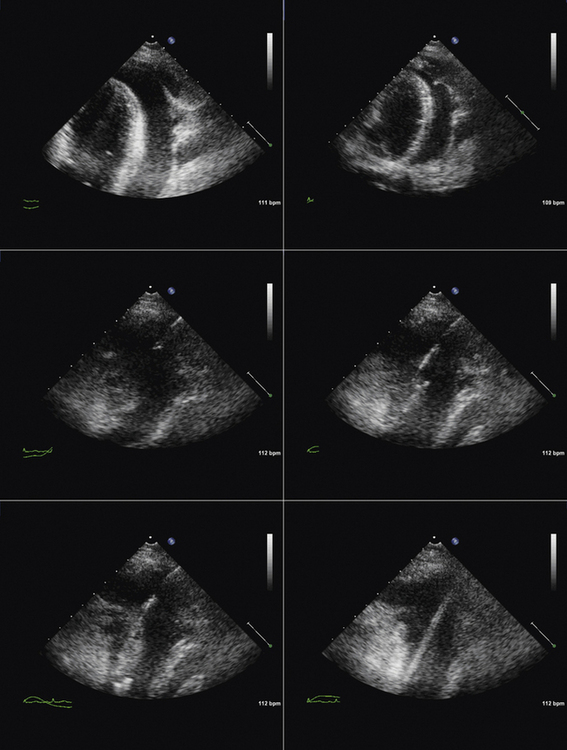

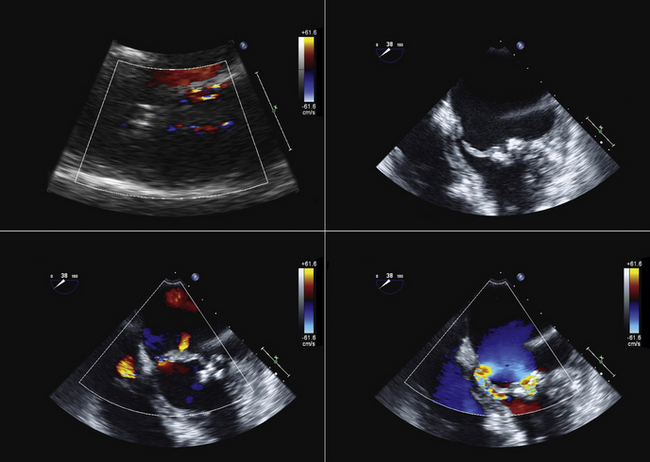

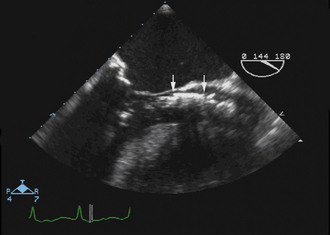

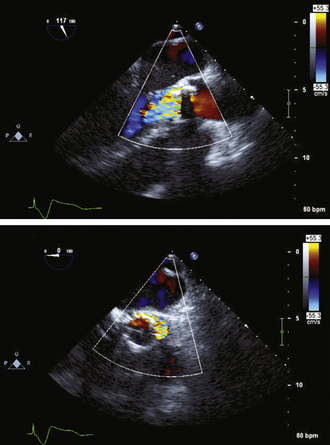

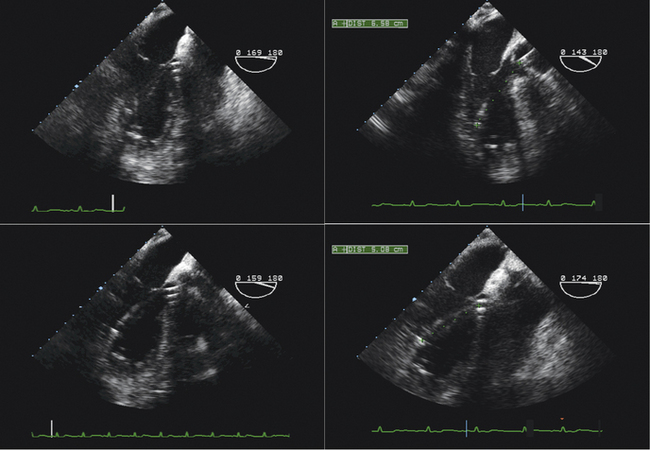

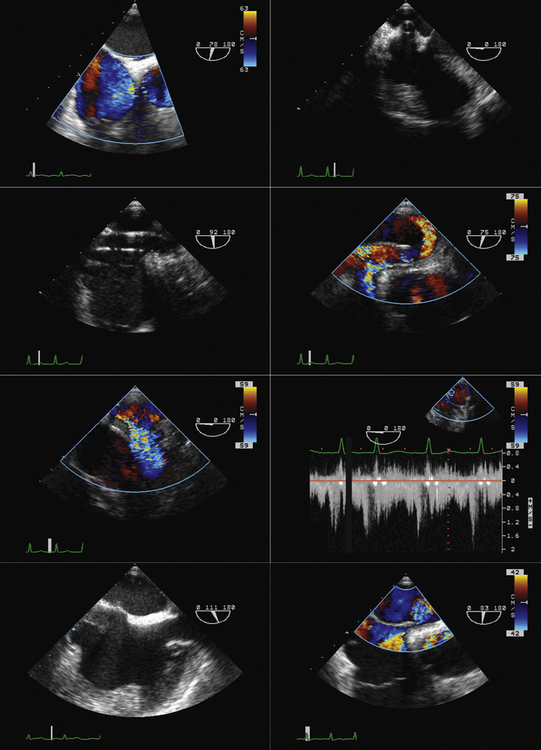

Intraprocedural Role

The long-axis view (~130 degrees) is used to guide deployment of the Edwards prosthesis. Ideally, the undeployed Edwards valve on the delivery system should be positioned across the aortic valve coaxial to the aorta. The ventricular end should be positioned up to 5 mm below the native aortic valve area, because there is a tendency for the percutaneous heart valve (PHV) deployment system to propagate incrementally toward the aortic root during deployment. The aortic end should be close to the tips of the native aortic valve leaflets to ensure full leaflet capture with deployment.

The long-axis view (~130 degrees) is used to guide deployment of the Edwards prosthesis. Ideally, the undeployed Edwards valve on the delivery system should be positioned across the aortic valve coaxial to the aorta. The ventricular end should be positioned up to 5 mm below the native aortic valve area, because there is a tendency for the percutaneous heart valve (PHV) deployment system to propagate incrementally toward the aortic root during deployment. The aortic end should be close to the tips of the native aortic valve leaflets to ensure full leaflet capture with deployment.

Identification of the ventricular and aortic rims of the prosthesis can be challenging, and knowledge of the PHV length (this may differ in the deployed and undeployed states), the use of high-frequency imaging, and manipulation of the probe are required to improve visualization. It should also be remembered that different iterations of the deployment systems have subtly different imaging characteristics.

Identification of the ventricular and aortic rims of the prosthesis can be challenging, and knowledge of the PHV length (this may differ in the deployed and undeployed states), the use of high-frequency imaging, and manipulation of the probe are required to improve visualization. It should also be remembered that different iterations of the deployment systems have subtly different imaging characteristics.

Hemodynamic instability often is observed during device positioning. This may be due to critical output obstruction by the undeployed PHV, but is thought sometimes to be related to reflexive changes in vagal output. Correct deployment position of the Edwards valve is essential so that the fabric portion of the prosthesis is fully opposed to the aortic annulus. Deployment in a position that is too ventricular is serious; it may result in immediate and life-threatening aortic regurgitation; incomplete capture of native aortic valve leaflets and restriction of anterior mitral valve leaflet motion also may be seen. Deployment in a position that is too aortic can result in coronary artery obstruction and can compromise the stability of the valve, risking valve embolization.

Hemodynamic instability often is observed during device positioning. This may be due to critical output obstruction by the undeployed PHV, but is thought sometimes to be related to reflexive changes in vagal output. Correct deployment position of the Edwards valve is essential so that the fabric portion of the prosthesis is fully opposed to the aortic annulus. Deployment in a position that is too ventricular is serious; it may result in immediate and life-threatening aortic regurgitation; incomplete capture of native aortic valve leaflets and restriction of anterior mitral valve leaflet motion also may be seen. Deployment in a position that is too aortic can result in coronary artery obstruction and can compromise the stability of the valve, risking valve embolization.

Edwards-Sapien valves usually are implanted under TEE guidance:

Edwards-Sapien valves usually are implanted under TEE guidance:

TEE can be helpful in assessing for aortic pathology that may occur during the procedure (e.g., dissection).

TEE can be helpful in assessing for aortic pathology that may occur during the procedure (e.g., dissection).

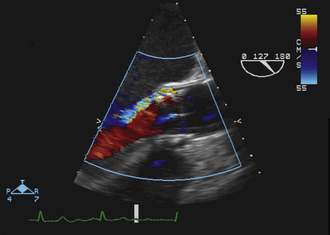

Post-procedural Assessment

Immediate post-procedural assessment by TEE

Immediate post-procedural assessment by TEE

Post-procedural Follow-up by Transthoracic Echocardiography

TTE for follow-up of PAV hemodynamics (gradients, area, regurgitation)

TTE for follow-up of PAV hemodynamics (gradients, area, regurgitation)

TTE for follow up of hemodynamic and morphologic response to PAV implantation (e.g., change in pulmonary artery pressure, LV mass changes)

TTE for follow up of hemodynamic and morphologic response to PAV implantation (e.g., change in pulmonary artery pressure, LV mass changes)

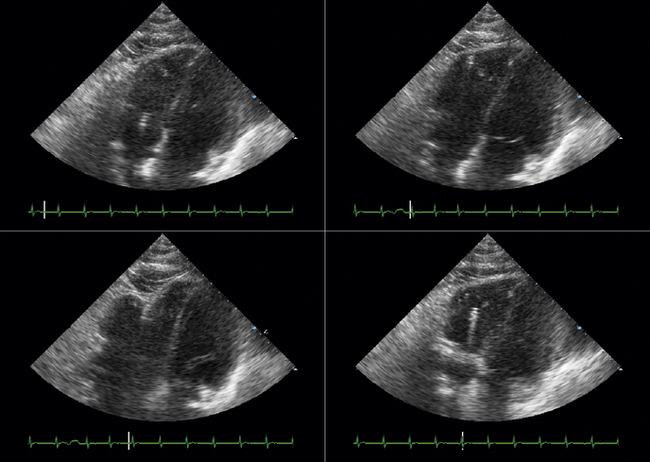

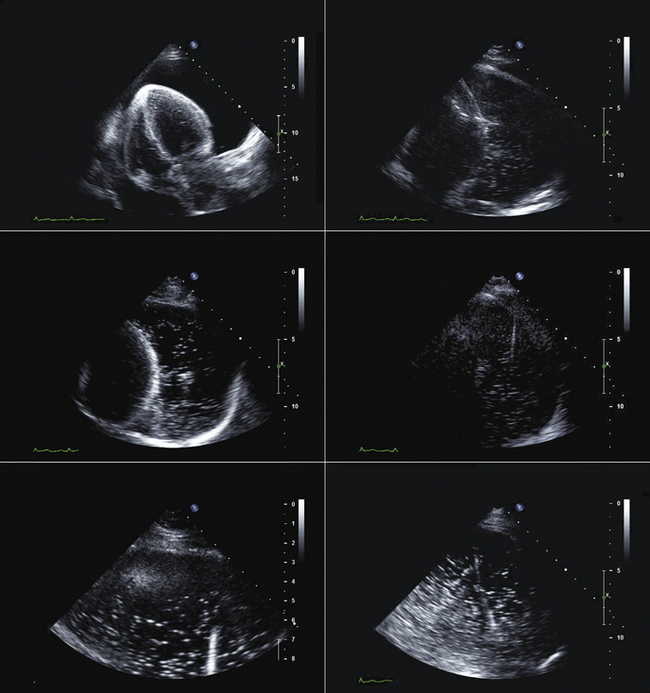

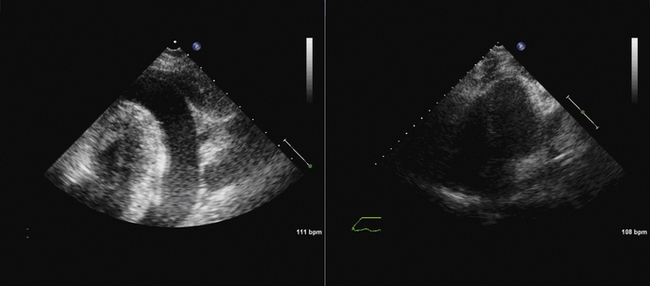

TTE or TEE for assessment of symptoms that develop after valve implantation (e.g., imaging for suspected endocarditis; Figs. 26-25 to 26-30)

TTE or TEE for assessment of symptoms that develop after valve implantation (e.g., imaging for suspected endocarditis; Figs. 26-25 to 26-30)

Intra-Aortic Counterpulsation Balloon Tip Localization

Sequence

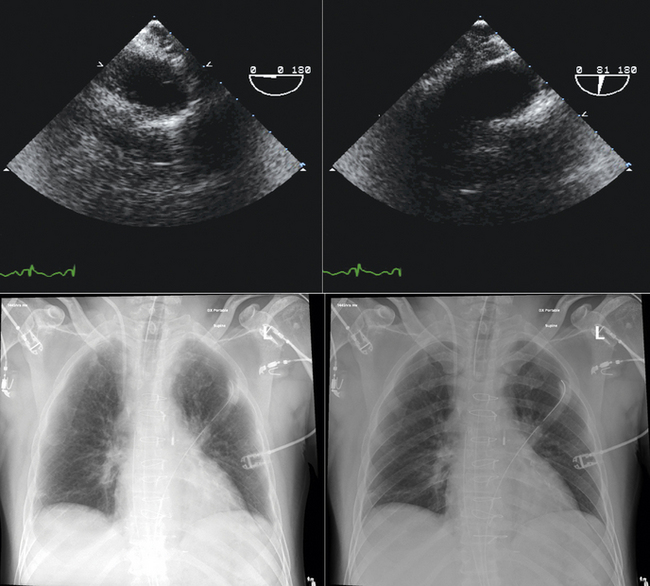

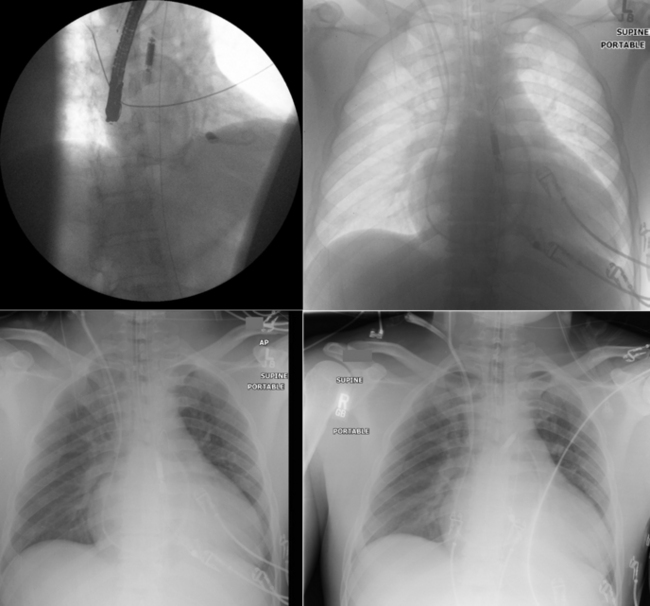

The tip of the intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon (IABP) is verified post-insertion by fluoroscopy or chest radiography. However, it is somewhat prone to movement, especially in patients who are transported.

The tip of the intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon (IABP) is verified post-insertion by fluoroscopy or chest radiography. However, it is somewhat prone to movement, especially in patients who are transported.

TEE is readily able to verify the tip location of the balloon. It should be in the very proximal descending aorta.

TEE is readily able to verify the tip location of the balloon. It should be in the very proximal descending aorta.

Impella and Left Ventricular Assist Device Insertion*

Rationale and Role

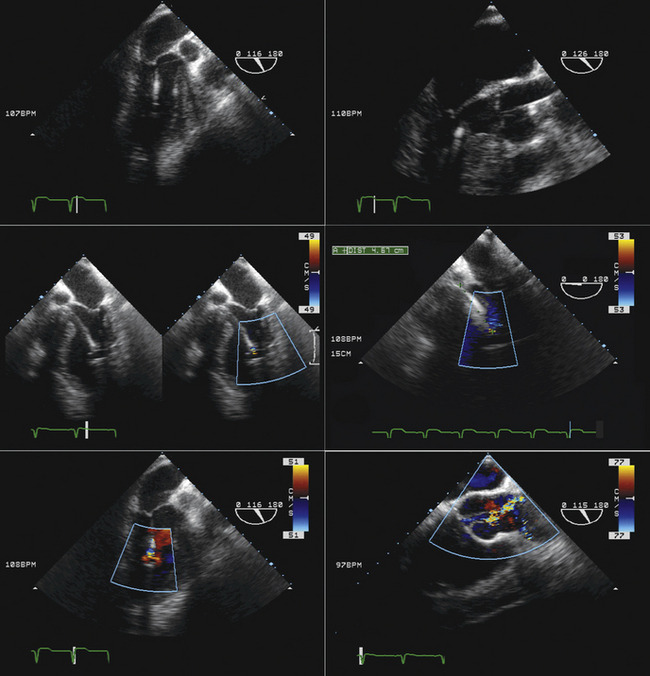

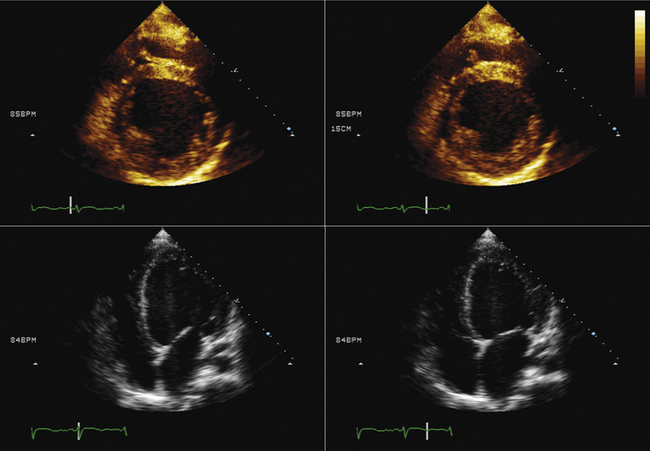

The Impella percutaneous ventricular assist devices (Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) typically are inserted percutaneously via the femoral artery (Impella 2.5) or via surgical cut-down (Impella 2.5 or 5). The device is advanced retrograde up the aorta, and positioned across the aortic valve such that the intake is within the LV, and the output is above the aortic valve. The component of the device within the LV is best oriented along the long axis of the LV. The presence of significant aortic insufficiency would preclude the device achieving efficiency.

The Impella percutaneous ventricular assist devices (Abiomed, Inc., Danvers, MA) typically are inserted percutaneously via the femoral artery (Impella 2.5) or via surgical cut-down (Impella 2.5 or 5). The device is advanced retrograde up the aorta, and positioned across the aortic valve such that the intake is within the LV, and the output is above the aortic valve. The component of the device within the LV is best oriented along the long axis of the LV. The presence of significant aortic insufficiency would preclude the device achieving efficiency.

Echocardiography is useful to exclude significant aortic valve disease (i.e., aortic stenosis that would preclude delivery of the device into the left ventricle and aortic insufficiency that would impair efficiency). TEE usually is employed to verify the correct location/position of the intake component within the left ventricle and of the output component within the aorta.

Echocardiography is useful to exclude significant aortic valve disease (i.e., aortic stenosis that would preclude delivery of the device into the left ventricle and aortic insufficiency that would impair efficiency). TEE usually is employed to verify the correct location/position of the intake component within the left ventricle and of the output component within the aorta.

Although these devices are deployed with fluoroscopic guidance, the combination of fluoroscopy and echocardiography—both two-dimensional and color Doppler—provides visualization of the wire and device (fluoroscopy and echocardiography) and the cardiac structures (echocardiography) such that the position and orientation of the device ensures optimal functioning

Although these devices are deployed with fluoroscopic guidance, the combination of fluoroscopy and echocardiography—both two-dimensional and color Doppler—provides visualization of the wire and device (fluoroscopy and echocardiography) and the cardiac structures (echocardiography) such that the position and orientation of the device ensures optimal functioning

Sequence

Transthoracic echocardiography

To exclude significant aortic valvar stenosis

To exclude significant aortic valvar stenosis

To exclude significant aortic valvar insufficiency

To exclude significant aortic valvar insufficiency

To exclude ‘mechanical’ complications of infarction

To exclude ‘mechanical’ complications of infarction

Transesophageal echocardiography

After exclusion of significant aortic valve disease and mechanical complications of infarction

After exclusion of significant aortic valve disease and mechanical complications of infarction

The location of the intake can be determined as follows:

The location of the intake can be determined as follows:

Confirm that the device is oriented to have the distal part along the long axis of the left ventricle toward the apex, rather than toward the wall.

Confirm that the device is oriented to have the distal part along the long axis of the left ventricle toward the apex, rather than toward the wall.

Confirm that the output component is ejecting blood within the aorta beyond the aortic valve.

Confirm that the output component is ejecting blood within the aorta beyond the aortic valve.

Pros

A practical means to use in the operating room or cardiac catheterization laboratory to ensure correct placement of the intake and the output components of the Impella device on their appropriate sides of the aortic valves

A practical means to use in the operating room or cardiac catheterization laboratory to ensure correct placement of the intake and the output components of the Impella device on their appropriate sides of the aortic valves

TTE may yield sufficient images, but TEE achieves more reliable visualization because most patients with cardiogenic shock are mechanically ventilated.

TTE may yield sufficient images, but TEE achieves more reliable visualization because most patients with cardiogenic shock are mechanically ventilated.

Cons

Visualization of the length of the Impella 5 device within the LV necessitates obtaining a long-axis view along which the device falls. If the plane of the device varies from that of the imaging plane, visual misunderstanding about the location of the end of the device may occur because it may be assumed that the last visualized portion of the device is the end.

Visualization of the length of the Impella 5 device within the LV necessitates obtaining a long-axis view along which the device falls. If the plane of the device varies from that of the imaging plane, visual misunderstanding about the location of the end of the device may occur because it may be assumed that the last visualized portion of the device is the end.

Familiarity with devices and with the two-dimensional and color Doppler imaging findings of their components is essential (Figs. 26-33 to 26-40).

Familiarity with devices and with the two-dimensional and color Doppler imaging findings of their components is essential (Figs. 26-33 to 26-40).

Surgical Ventricular Assist Device Placement and Function

Cons

Fluoroscopy generally is used to guide IABP placement, especially because most are placed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The role of TEE is limited to verification of correct placement without fluoroscopy (Fig. 26-41).

Fluoroscopy generally is used to guide IABP placement, especially because most are placed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. The role of TEE is limited to verification of correct placement without fluoroscopy (Fig. 26-41).

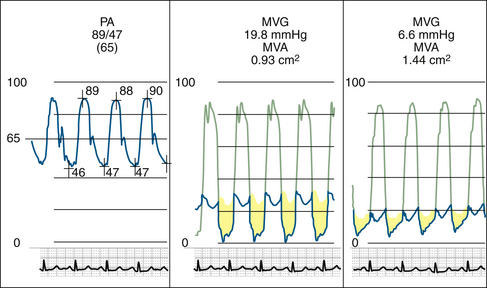

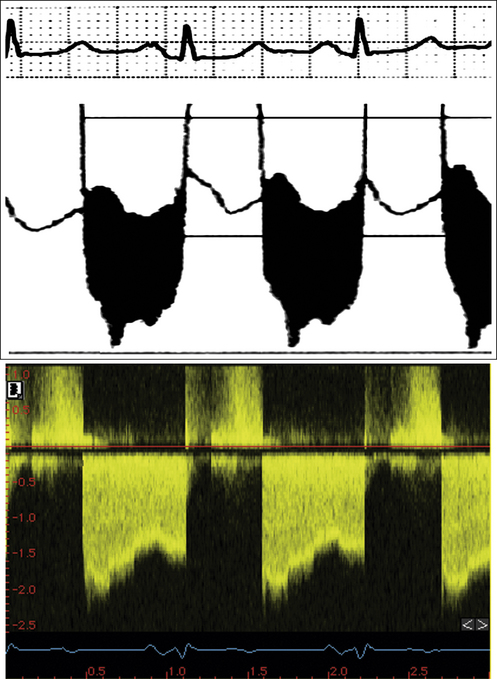

Figure 26-21 Mitral valve gradients and the corresponding spectral Doppler display, which yields gradient calculation.

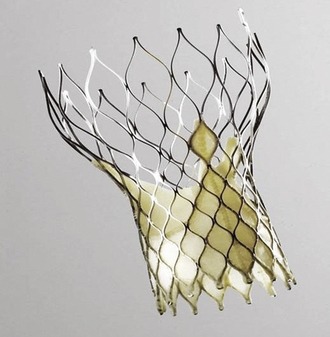

Figure 26-23 The CoreValve prosthesis.

(Courtesy of CoreValve ReValving System, CoreValve Inc., Irvine, California.)

Figure 26-24 The Edwards-Sapien prosthesis.

(Courtesy of Edwards Life-Sciences Inc., Irvine, California.)

1. Caves P.K., Stinson E.B., Billingham M., Shumway N.E. Percutaneous transvenous endomyocardial biopsy in human heart recipients. Experience with a new technique. Ann Thorac Surg. 1973;16(4):325-336.

2. Billingham M. Endomyocardial biopsy diagnosis of acute rejection in cardiac allografts. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;33:11-18.

3. Deckers J.W., Hare J.M., Baughman K.L. Complications of transvenous right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy in adult patients with cardiomyopathy: a seven-year survey of 546 consecutive diagnostic procedures in a tertiary referral center. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19(1):43-47.

4. Sakakibara S., Konno S. Endomyocardial biopsy. Jpn Heart J. 1962;3:537-543.

5. Miller L.W., Labovitz A.J., McBride L.A., et al. Echocardiography-guided endomyocardial biopsy. A 5-year experience. Circulation. 1988;78(5 Pt 2):III99-III102.

6. Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Noor A.M., Eskilsson J., Persson S. Safety of transvenous right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy guided by two-dimensional echocardiography. Clin Cardiol. 1993;16(6):487-492.

7. Weston M.W. Comparison of costs and charges for fluoroscopic- and echocardiographic-guided endomyocardial biopsy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(8):839-840.

8. Williams G.A., Kaintz R.P., Habermehl K.K., et al. Clinical experience with two-dimensional echocardiography to guide endomyocardial biopsy. Clin Cardiol. 1985;8(3):137-140.

9. Ragni T., Martinelli L., Goggi C., et al. Echo-controlled endomyocardial biopsy. J Heart Transplant. 1990;9(5):538-542.

10. Appleton R.S., Miller L.W., Nouri S., et al. Endomyocardial biopsies in pediatric patients with no irradiation. Use of internal jugular venous approach and echocardiographic guidance. Transplantation. 1991;51(2):309-311.