Chapter 25 EATING DISORDERS

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

INTRODUCTION

The key diagnostic features of AN are:

ASSESSMENT

History

Family structure and history, as well as history of comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions, are also important information to record at the time of initial assessment.

Physical findings

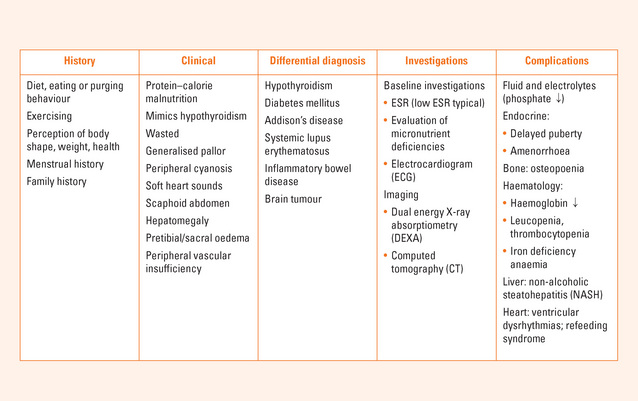

The protein–calorie malnutrition (PCM) that accompanies AN affects every organ in the body. The clinical presentation may have a number of features in common with hypothyroidism (Table 25.1); mentation and locomotion are slowed, hypothermia, constipation, pretibial oedema may be present, however patients do not have a goitre and thyroid hormones (thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH] and thyroxine [T4]) remain within normal parameters. Triiodothyronine (T3; measured by radioimmunoassay) is depressed commensurate with the degree of PCM, and recovers with correction of the malnutrition.

TABLE 25.1 Medical differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa

The abdomen is scaphoid and skin over the anterior abdominal wall is lax. Muscles of the anterior abdominal wall are typically decreased permitting palpation of abdominal organs easily. An enlarged fatty liver (with a soft, smooth, non-tender lower border) is commonly detected. Stool in the sigmoid colon is also easily palpable in the left lower quadrant.

Criteria for medical admission

RESUSCITATION

Measures to support the circulation are of the highest priority as invariably neither the airway nor breathing is compromised. Care must be taken not to use fluid replacement routinely, as cardiac failure is relatively easily induced in patients with PCM by volume overload. In particular, for those patients who have been chronically malnourished (i.e. over 6 months) circulatory changes should be induced slowly; and the adaptive physiological changes producing a low volume, low pressure circulation corrected over several days to a week or so depending on the severity of the PCM at presentation.

REFEEDING

In addition to having sufficient energy, the daily intake needs to contain a balance of macronutrients. High-quality proteins are important for rebuilding lost lean tissue mass. It is also important that nutritional rehabilitation be supported by healthy (resistance) exercising. A supervised and graded programme offers potential benefit, though these have not been scientifically investigated to date.

MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS

Endocrine

Amenorrhoea is considered one of the clinical criteria to establish the diagnosis, by DSM-IV criteria. Secondary amenorrhea is hypothalamic in origin, and it is due in part to suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Other factors include stress, the additive effects of malnutrition, weight loss, starvation and strenuous exercise. A weight of approximately 90% of standard body weight (50th centile for age, sex and height), on average, is required for resumption of menses to occur, and serum oestradiol levels at follow-up best track this process. However, the weight at which an individual patient with anorexia nervosa may resume menses is variable. The use of ancillary methods such as measures of body composition and serum oestradiol may be used to predict this significant landmark in the treatment of patients with eating disorders.

Haematological

Bone marrow hypoplasia and its implications in this population have been described. In children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa, the most commonly seen haematological changes include normal or marginally low haemoglobin and haematocrit with abnormal erythrocyte indices, showing increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC). These macrocytic changes are rarely associated with folate or vitamin B12 deficiency in this patient population; but need to be considered when present. Other abnormalities include leucopenia and thrombocytopenia. All of these changes are reversible with weight restoration and nutritional rehabilitation.

Renal

Should there be persistent hypokalaemia, as a result of chronic vomiting or diuretic abuse, as in bulimia nervosa and patients who purge in anorexia nervosa, vacuolation of the renal tubules has been observed resulting in impaired tubular function affecting fluid and electrolyte balance.

PROGNOSIS

The morbidity of AN is minimised with early correction of the PCM (kwashiorkor). Ongoing effects to bone health and other organs have been demonstrated. There remains concern that the changes to brain structure and function, particularly in the more malnourished patients, do not fully recover even after nutritional rehabilitation. Protracted PCM certainly can result in organ failure as illustrated by the diffuse glomerular sclerosis and renal failure seen in a small group of chronically malnourished patients.

SUMMARY

The overall (crude) mortality of this condition remains high. Despite the greater potential for medical complications because of the impact on growth and pubertal development, AN in children and adolescents carries a better prognosis. Early correction of protein calorie malnutrition increases the potential for recovery before chronic and irreversible organ changes occur. Early intervention and particularly early nutritional rehabilitation minimises the impact of AN on physical health. Weight restoration and nutritional rehabilitation remain the cornerstones of biological treatment with a two-track approach and appropriate psychosocial interventions to achieve recovery from this devastating illness (Figure 25.1).

Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:293-309.

Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Anorexia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:310-320.

Herzog DB, Greenwood DN, Dorer DJ, et al. Mortality in eating disorders: a descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:20-26.

Kohn MR, Golden NH, Shenker IR. Cardiac arrest and delirium: presentations of the refeeding syndrome in severely malnourished patients with anorexia nervosa. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:239-243.