85 Eating Disorders

Etiology and Pathogenesis

In the United States, it is estimated that the lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa is 0.5% and 1% to 3% for bulimia nervosa. Ten percent of all eating disorder patients are males. The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) outlines the criteria for the diagnosis of anorexia nervous and bulimia nervosa as summarized in Box 85-1. Although a main feature of the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is a body weight that is below 85% of that expected for age and height, for younger patients, the diagnosis can be made without weight loss from previous visits if the patient fails to make the expected weight gains of normal growth. The DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa require recurrent episodes of regular binge eating with inappropriate compensatory behaviors to avoid weight gain. Eating disorder not otherwise specified encompasses eating disorders that do not meet full DSM-IV criteria for either anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Some reports show that more than 50% of adolescents with eating disorders fall into this category; these patients still require appropriate treatment because they have the same underlying eating behaviors and can develop the same life-threatening complications.

Box 85-1

Overview of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa Diagnostic Criteria

Anorexia Nervosa Diagnostic Criteria

Bulimia Nervosa Diagnostic Criteria

Based on American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 4, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

Clinical Presentation

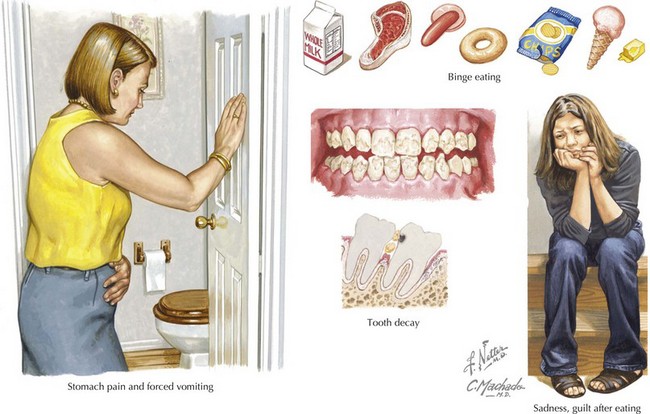

Pediatricians may be alerted to the early stages of an eating disorder during their evaluations at the patient’s routine and acute visits. Weight loss or failure to gain weight may be an initial finding. Vital signs may also reveal bradycardia, a lower blood pressure, or hypothermia compared with previous visits. A patient with anorexia nervosa may present with thinning of scalp hair, lanugo or fine hair growth on the extremities, dry skin, acrocyanosis, and bruising or calluses related to overexercising. Bulimia nervosa may be considered if the pediatrician notes scarring or abrasions in the back of the mouth, parotid gland hypertrophy, dental enamel erosions, or calluses on the dorsum of the fingers known as Russell’s sign, which result from self-induced vomiting. Some of the symptoms of patients with bulimia nervosa are summarized in Figure 85-1.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of eating disorders includes other medical and psychiatric conditions that can account for the symptoms of weight loss or, in the case of bulimia, chronic vomiting or electrolyte abnormalities (Box 85-2). These diagnoses need to be excluded by history or laboratory evaluation because the resulting malnutrition associated with these chronic conditions can look very much like an eating disorder.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Identifying and treating eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):204-211.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. text revision. ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders, ed 3. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006.