CHAPTER 8 Eating Disorders

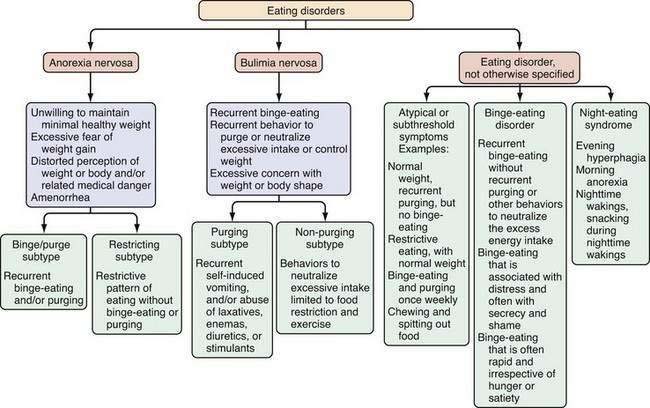

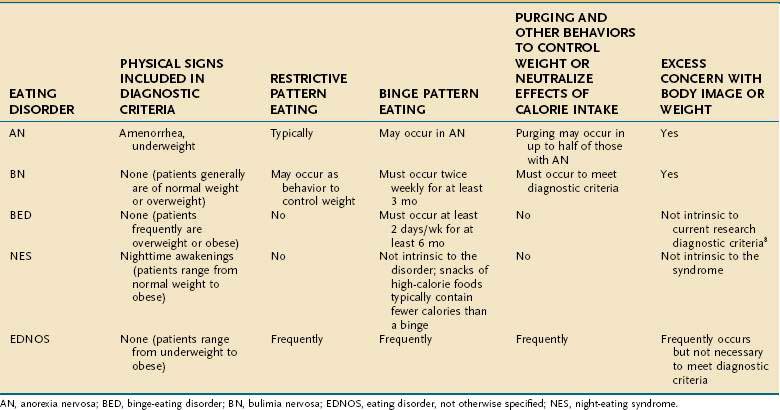

Eating disorders are mental illnesses characterized by disturbances in weight control, body image, and/or dietary patterns. Diagnostic categories include (1) anorexia nervosa (AN); (2) bulimia nervosa (BN); and (3) eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS; Fig. 8-1; Table 8-1). Several variants of EDNOS, such as binge-eating disorder and night eating syndrome, are well-described in the literature. The focus of this chapter is eating disorders in adults; other disturbances in eating that typically have onset in infancy and early childhood, such as pica, rumination syndrome, and feeding disorder of early childhood, are not discussed here. Although eating disorders are classified as mental illnesses, their associated behaviors commonly result in and present with medical sequelae, many of which are gastrointestinal. Because associated chronic undernutrition, overweight, and/or purging behaviors often result in serious medical complications that can be chronic, individuals with eating disorders benefit from the ongoing care of a multidisciplinary treatment team. Indeed, eating disorders (AN and BN) are among the mental disorders with the highest mortality risk.1

Table 8-1 Behaviors Used to Neutralize Excessive Food Intake or to Prevent Weight Gain

| Purging behaviors |

| Non-purging behaviors |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Eating disorders have been described across diverse global settings, although epidemiologic data are best established for populations in North America and Europe. The incidence rate for AN is approximately eight cases/100,000 population/year, with a point prevalence of AN estimated at 0.3% in young women of the United States and Western European general populations. BN is more common than AN, with an incidence of 12 cases/100,000 population/year in the United States and Western Europe2 and a 12-month prevalence of 0.5% among adult women in the United States. Lifetime prevalence estimates for U.S. women based on the National Comorbidity Study Replication (NCS-R) are 0.9% for AN and 1.5% for BN; U.S. men have a lifetime prevalence of 0.3% for AN and 0.5% for BN.3 The most common presentation of an eating disorder in outpatient settings is EDNOS, although fewer prevalence data are available for this broad and heterogeneous category. One large study from Portugal reported a prevalence of 2.37% for EDNOS in female students in grades 9 to 12.4 Relatively high prevalence rates also are reported for specific symptoms associated with disordered eating. For example, in 2007, 6.4% of school-going female adolescents in the United States reported vomiting or laxative use, and 16.3% reported fasting within the previous month to lose weight.5 Within the diagnostic category of EDNOS, there is great interest in a clinical variant termed binge-eating disorder (BED). The lifetime prevalence of BED in the United States is 3.5% for adult women and 2.0% for adult men. Additional variants of disordered eating (that are not classified as distinct disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM) include the night eating syndrome (NES) and nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder (NSRED). The prevalence of NES in young adult women has been reported as 1.6%6 and of NSRED as 0.5%.7

Eating disorders occur across ethnically and socioeconomically diverse populations, but each of the eating disorders is more common in women than in men. Males account for less than 10% of individuals with AN, 10% of those with BN, 34% of those with NES, and 40% of those with BED.8,9

CAUSATIVE FACTORS

Although incompletely understood, the cause of eating disorders is almost certainly multifactorial, with psychodevelopmental,10 sociocultural,11 and genetic12 contributions to risk. For example, exposure to risk factors for dieting appears to elevate risk for BN,13 just as childhood exposure to negative comments about weight and shape elevate risk for BED.14 Body dissatisfaction in a social context in which thinness,15,16 self-efficacy, and control are valued may be an important means whereby dieting is initiated and disordered eating attitudes and behaviors ensue. Dietary restraint may precipitate a cycle of hunger, binge eating, and purging.17 Among numerous risk correlates, childhood gastrointestinal (GI) complaints have been found associated with earlier age of onset and greater severity of BN in a retrospective study,18 and picky eating and digestive problems were found prospectively associated with AN in adolescence.10

SATIETY

Serotonin has long been a focus of attention for its possible role in disrupted satiety. There is substantial evidence that altered 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; serotonin) functioning contributes to dysregulated appetite, mood, and impulse control in eating disorders and persists after recovery from AN and BN, possibly reflecting premorbid vulnerability.19,20 There also is evidence that cholecystokinin (CCK) levels are altered in eating disorder populations. Findings for AN are inconsistent: There is some evidence that young women with AN have high levels of pre- and postprandial CCK, which may impede treatment progress by contributing to postmeal nausea and vomiting,21,22 whereas other reports have shown decreased CCK compared with that of controls.23 In those with BN, there is consistent evidence for an impaired satiety response, characterized by a blunted postprandial CCK response and satiety, as well as delayed gastric emptying.24,25 In contrast, individuals with BED and obesity do not differ in postmeal CCK responses from those with obesity but no BED.26 The relationships between CCK, binge eating, and BMI need further clarification. Lastly, protein tyrosine (PYY) functioning also appears to be dysregulated in BN and AN, but not in BED. Young women with AN have higher levels of PYY, the intestinally derived anorexigen that elicits satiety, compared with controls, perhaps contributing to reduced food intake.27 In individuals with BN, expected elevations in PYY after meals are blunted,28,29 possibly playing a role in impaired satiety. A recent report found no differences between BED and non-BED groups in fasting levels and postmeal changes in PYY.30

APPETITE

The orexigenic peptide ghrelin is of interest for its role in eating disorders because it influences secretion of growth hormone (GH), stimulates appetite and intake, induces adiposity, and is implicated in signaling to the hypothalamic nuclei involved in energy homeostasis. There are two consistent findings in the literature examining ghrelin and AN: (1) circulating ghrelin levels are elevated, likely a consequence of prolonged starvation31,32; and (2) GH and appetite responses to ghrelin are blunted, suggesting altered ghrelin sensitivity.33,34 In BN, plasma levels of ghrelin are normal or elevated28,29; of most interest is the postprandial blunted response (i.e., reduced suppression of ghrelin35). Investigations of ghrelin functioning in individuals with BED have reported lower circulating levels of pre- and postmeal ghrelin, possibly reflecting down-regulation in response to chronic overeating and smaller decreases in ghrelin after eating.30

ENERGY STORAGE

Leptin and adiponectin are hormonal signals associated with longer term regulation of body fat stores. Leptin is also directly implicated in satiety through its binding to the ventral medial nucleus of the hypothalamus, an area termed the satiety center. Leptin and adiponectin are both altered in patients with eating disorders. A number of studies have found evidence for hyperadiponectinemia and hypoleptinemia in populations of underweight AN with reversal following restoration of weight36,37; increased adiponectin levels may act protectively to support energy homeostasis during food deprivation. Individuals with BN also exhibit decreased plasma levels of leptin, which are inversely correlated with length of illness and severity of symptoms.38 The mechanism of altered leptin functioning in BN is unclear because blunted postmeal leptin levels are not observed in individuals with BED.26

ONSET AND COURSE

AN and BN most commonly have their onset in adolescence,39 and BED usually manifests in the early 20s,40 but eating disorders can occur throughout most of the lifespan and appear to be increasing in frequency in middle-aged and older women.41,42 Diagnostic migration from one eating disorder category to another is common.43

Lifetime comorbidity of AN, BN, and BED with other psychiatric disorders is high at 56.2%, 94.5%, and 63.6%, respectively.3 Mortality associated with AN and BN combined is five times higher than expected and is one of the highest mortality rates among mental disorders.1 Some data support the chronicity of AN, reporting that slightly under half of survivors with AN make a full recovery, with 60% attaining a normal weight and 47% regaining normal eating behavior; 34% improve but only achieve partial recovery, whereas 21% follow a chronic course.44 Other data suggest that recovery rates for AN may be more favorable than previously believed,3 with one large twin cohort study reporting a five-year clinical recovery rate of 66.8%.45 In contrast, after a five-year follow-up of 216 patients with BN and EDNOS, 74% and 78% of patients, respectively, were still in recovery.46 In a six-year longitudinal study of patients with BED, 43% of individuals continued to be symptomatic.47 In summary, despite well-established treatments available for the eating disorders, up to 50% of treated individuals continue to be symptomatic.48 Some prevention strategies developed for eating disorders show promise, including programs that induce cognitive dissonance about the “thin ideal.”49,50

DIAGNOSIS AND EVALUATION

A substantial percentage of individuals with eating disorders in the United States do not receive treatment for this problem.3 Despite clear diagnostic criteria for the eating disorders, clinical detection often is problematic and up to 50% of cases may go unrecognized in clinical settings. Moreover, individuals with eating disorders are often reluctant to disclose their symptoms,51 and those with BN and BED can have a normal physical examination. Although individuals with AN are underweight by definition, this is easily missed in clinical settings. Even when noted on evaluation, the medical seriousness of low weight is frequently unappreciated.52 Finally, when an eating disorder is suspected or confirmed, patients may decline or avoid mental health care. Indeed, a feature of AN can be denial of the medical seriousness of symptoms.8 Given that many individuals with eating disorders initially present in primary care or medical subspecialty settings, recognition of clinical signs and symptoms across diverse health care settings will facilitate appropriate referrals and make diagnostic evaluation and treatment plans more efficient. One study has reported that individuals with BN are more likely to seek help for their GI complaints prior to seeking treatment for their eating disorder.53 Thus, familiarity with the diagnostic features and gastrointestinal complications of eating disorders will help to identify the most appropriate interventions, including the full spectrum of treatment resources available, for a comprehensive treatment plan.

Formal screening for eating disorders can be time-consuming, and although shorter measures are being developed,54 these have many limitations in clinical settings.55 When an eating disorder is suspected, however, a directed clinical interview about restrictive or binge eating and inappropriate compensatory measures to control weight (see Table 8-1) is essential in determining the scope and severity of symptoms that underlie specific GI complaints and pose medical risk.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by an unwillingness or incapacity to maintain a minimally normal weight (commonly described as at least 85% of expected weight or a body mass index [BMI] of 17.5 kg/m2), fear of gaining weight (despite being thin), a disturbance in the way weight is experienced (e.g., a denial of the medical seriousness of being underweight or feeling fat despite emaciation), and amenorrhea (in postmenarcheal females). Individuals with AN typically restrict their food selections and caloric intake, but approximately half of those with AN also routinely binge-eat and/or engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as induced vomiting or laxative use to prevent weight gain (see Fig. 8-1). AN is subdivided further into restricting type (i.e., those who primarily control their weight through dieting, fasting, or exercising) and binge-eating–purging type (i.e., those who routinely purge calories to control weight and may or may not routinely binge-eat).8 In middle-aged and older women, new-onset AN may present in conjunction with difficulty making life transitions and fear of aging.42 The diagnosis of AN may be delayed when patients present to a GI specialty practice without disclosing their concerns and behaviors relating to weight. Presentation with GI complaints, even if related to real symptoms or disease, can sometimes prove to be a red herring, drawing attention away from and delaying diagnosis of an eating disorder. One study evaluated 20 consecutive patients presenting to a GI practice who were ultimately diagnosed with an eating disorder, and found that patients did not receive a diagnosis of an eating disorder for an average of 13 months after presentation. Notably, all patients stated a desire to gain weight and denied attempts to lose weight via exercise, purging, or dietary restriction.56 Individuals with AN are not always able or willing to frame their difficulty maintaining a healthy weight as intentional; thus, the diagnosis initially may be unsuspected and delayed.

BULIMIA NERVOSA

The clinical hallmark of BN is recurrent binge eating accompanied by inappropriate compensatory behaviors to control weight or to purge calories consumed during a binge. On average, these behaviors must occur twice weekly for at least three months to meet diagnostic criteria.8 Also intrinsic to the diagnosis of BN is the excessive influence of weight and/or shape on self-image.

By definition, binge eating is consumption of an unusually large amount of food during a “discrete period of time” (i.e., not overeating or grazing all day), accompanied by the feeling that the eating cannot be controlled.8 Many patients describe an emotional numbing during the period of eating. For some, this state appears to motivate the bingeing. Most clinicians are familiar with self-induced vomiting as the primary purging behavior, but individuals with BN often use alternative or additional means of preventing weight gain, including abuse of laxatives and/or enemas, diuretics (especially among health care workers), stimulants (including methylphenidate, cocaine, ephedra, and caffeine), underdosing of insulin (for those with diabetes mellitus), fasting or restrictive eating, and excessive exercise (see Table 8-1). Intentional consumption of gluten to promote weight loss in adolescents with celiac disease also has been reported.57

Whereas most compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain fall within the diagnostic subtype of purging BN, excessive exercise and fasting are behaviors categorized within the subtype of nonpurging BN.8 Because of the absence of the more classic purging behaviors and because of their frequent indistinct nature, this variant of BN often is challenging to identify. As with overeating and dieting, it frequently is difficult to determine the line between culturally normative and pathologic behavior with excessive exercise. Generally, clinical suspicion should be raised when an individual continues to exercise despite an injury or illness, or if he or she is exercising routinely in excess of what a coach is recommending for the team.

It is recommended that clinicians explore the presence of purging behaviors if an eating disorder is suspected. Although it is not certain that a patient will respond candidly, individuals probably are more likely than not eventually to disclose information about symptoms when asked.51 Some patients report feeling relieved when clinicians pose such questions if they previously had not been able to discuss their symptoms. On occasion, however, patients report learning about techniques from clinicians’ questions, so it is advisable to provide a psychoeducational context for the questions (e.g., by conveying serious physical consequences associated with the behavior, such as ipecac use) and to avoid introducing information about a dangerous behavior (e.g., underdosing insulin), depending on the clinical context. Patients also benefit from learning that treatment is available and that their clinicians understand the illness.

Whereas all these purging and other behaviors aimed at neutralizing calorie intake and controlling weight can pose medical risks when chronic, some of them pose more immediate, and potentially lethal, consequences. Patients should be informed of these acute life-threatening risks and steps should be taken to eradicate such behaviors immediately. For example, because of the serious neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, and risk of death associated with repeated syrup of ipecac ingestion,58 its ongoing use is a clinical emergency and may require immediate hospitalization. Many patients are unaware of the serious risk associated with syrup of ipecac use. Similarly, ephedra, now banned in the United States, poses risk of stroke or adverse cardiac events, even in young adults.59 Some ephedra-free supplements marketed as weight loss agents also may be proarrhythmic and pose medical risks.60 Although patients find it difficult to abstain from purging behaviors, they may be willing to substitute less immediately harmful behaviors while treatment is initiated.

EATING DISORDER NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

EDNOS covers a broad range of clinical manifestations, including atypical symptoms, symptoms of BED, symptoms consistent with NES, and subthreshold, yet clinically significant, eating disorders. Although EDNOS is a residual category, it nonetheless is the most commonly diagnosed eating disorder in outpatient settings, and therefore there is much interest in refining diagnostic categories of eating disorders.61 EDNOS currently includes eating disorders that do not meet threshold criteria for duration or frequency for AN or BN as well as BED, NES, purging disorder and other atypical variants. Diagnostic classification of eating disorders will be updated in the DSM-V, with an expected publication date of 2012.

BINGE EATING DISORDER

BED is a variant of EDNOS, although there is a substantial literature to support its prevalence and consistent response to specific therapeutic strategies. Like BN, BED is characterized by recurrent binge-eating. To meet provisional criteria for BED, the binge eating episodes must occur two days per week, on average, for at least six months. Unlike BN, however, BED is not associated with recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain. BED is distinguished from nonpathologic overeating by several possible associated symptoms, including rapid eating, eating irrespective of hunger or satiety, eating alone because of shame, and negative feelings after a binge.8 Apart from overweight or obesity, BED patients frequently present without any specifically associated physical findings. Although in some cases binge eating associated with BED may cause or perpetuate weight gain, many with BED develop symptoms only after they have become overweight. Individuals with BED frequently are distressed enough about their symptoms to seek medical help, although they may present seeking a solution to their weight gain rather than their binge eating. A substantial percentage of patients seeking weight loss treatment will have comorbid BED or NES. Therefore, medical subspecialists are likely to encounter these patients before they have been diagnosed with BED.

NIGHT EATING SYNDROME AND NOCTURNAL SLEEP-RELATED EATING DISORDER

NES is a pathologic eating pattern that may be considered a variant of EDNOS. First described in 1955,62 it, too, is characterized by recurrent bouts of overeating—but not necessarily bingeing—without associated inappropriate compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain. As such, some individuals may appear to meet criteria for NES and BED, but these are distinct syndromes with relatively little overlap,7,63 and proposed criteria for the syndrome exclude a concomitant diagnosis of BN or BED.64 There is no clear consensus on core criteria for NES, although most investigators propose morning anorexia, evening hyperphagia, and sleep disturbance (operationalized in various ways); some propose the additional criterion of eating in relation to sleep disturbance, such as during a nighttime awakening.65 In one study, NES in obese subjects was associated with an average of 3.6 awakenings/night compared with just 0.3 awakenings/night for matched controls. Subjects with NES ate during 52% of their awakenings, taking in a mean of 1134 kJ/episode, considerably less than the usual intake of a binge associated with BN or BED.64 NES also can occur in nonobese individuals66 but is more common in the obese and may contribute to poor outcome in weight loss treatment programs.64,67 NSRED is also characterized by nighttime snacking, but individuals typically are totally or partially unconscious (e.g., they are in stage 3 or 4 sleep) during the snacking and frequently do not remember it.7

PURGING DISORDER

Emerging evidence raises the possibility of an additional distinctive eating disorder variant characterized by recurrent purging symptoms in the absence of clinically significant binge pattern eating. The proposed name for this diagnostic category is purging disorder. Crossover between this variant and BN appears to be rare, lending support to the hypothesis that this represents a distinctive clinical phenomenon68; data also support comparable severity to BN. Lifetime prevalence of purging disorder has been estimated as 1.1% to 5.3% of young adult women. Course, outcome, and treatment strategies for purging disorder require further research.69

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of the eating disorders includes evaluation and exclusion of medical causes of weight loss, weight gain, anorexia, hyperphagia, vomiting, and other associated symptoms. These considerations are especially germane in cases of atypical or early- or late-onset eating disorders.42 Medical causes of appetite and/or weight loss include hyperthyroidism, diabetes, malignancy, and infectious diseases, among the systemic disorders, and substance abuse, depression, dementia, delirium, and psychosis. Illnesses associated with weight gain include hypothyroidism, Cushing’s disease, and organic brain disease. The differential diagnosis of hyperphagia is broad and includes Prader-Willi syndrome, dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease), and intracranial lesions. Hyperphagia also has been associated with the use of certain medications, particularly many of the psychotropic agents (e.g., lithium, valproate, tricyclic antidepressants, mirtazapine, and conventional and atypical antipsychotic agents), pregnancy,70 and poststarvation refeeding.71

Psychiatric illnesses associated with loss of appetite and weight loss include major depression, anxiety, and substance-use disorders. Moreover, comorbid psychiatric illness is common among those with eating disorders,3 and frequently complicates their diagnosis and treatment. Thus, identification of excessive concern with weight and food intake, unrealistic or inappropriate weight goals, or resistance to attempts to restore normal weight and/or limit excessive exercise can be helpful in distinguishing an eating disorder from another psychiatric illness or in revealing the presence of an underlying comorbid eating disorder. Because individuals with BN and EDNOS can have an unremarkable physical examination on presentation, the diagnosis may remain obscure until the patient discloses his or her symptoms, or until the clinician suspects an eating disorder based on other elements of the clinical history (e.g., weight fluctuations or menstrual irregularities).

Although there potentially is much phenomenologic overlap among the eating disorders and individuals do cross over from one diagnostic category to another (Table 8-2),43 categories are mutually exclusive, according to DSM-IV* diagnostic criteria.8 Even though a transdiagnostic approach to eating disorders classification and treatment has been proposed,72 differing responses to treatment make it desirable to establish a clear diagnosis to optimize care. A weight criterion distinguishes anorexia nervosa from bulimia nervosa in some cases. Individuals who are substantially underweight (e.g., 85% or less of expected body weight) and who otherwise meet criteria for AN most likely should be classified as having AN, even if bingeing, purging, or both are present. Individuals with BED or BN also can have symptom overlap. BN is distinguished by recurrent purging and other behaviors directed at neutralizing excessive calorie intake so as to prevent weight gain, as well as an excessive concern with weight.

NUTRITIONAL EVALUATION

There are several established means for evaluating nutritional status in the office, central to which is measuring weight and height (see Chapter 5). Assessment of the appropriateness of weight for height is one of the key factors intrinsic to determining the urgency of medical and psychiatric care. For patients with AN, it is important not to rely on self-reported weight, given the strong possibility of an inaccurate report. Individuals with AN often go to great effort to conceal their low weights. For example, some patients “water load” prior to a clinical encounter, some attach weights to themselves, and others layer loose and bulky clothing to create the illusion of being of normal weight. Assessment of weight, therefore, should factor in the possibility that a patient may wish to conceal a low weight or weight loss. Some clinicians will find it helpful to have a scale in a private area (i.e., not in a hallway) and a clear and consistent protocol for weighing patients with AN. This might include asking them to void prior to being weighed, to change into a hospital gown, and to remove heavy jewelry. When patients have a history of consuming water prior to an appointment to increase their measured weight, it may be helpful to check a urine specific gravity in order to adjust interpretation of the office weight.

Although BMI may not be an appropriate standard for evaluating a healthy weight status in professional athletes, with relatively high lean muscle mass, and in some ethnic groups (e.g., Polynesians may have a different cut point for obesity73), BMI generally is appropriate for men and women aged 18 years or older. A BMI within the range of 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 for men and women is considered normal. A BMI of 17.5 kg/m2 or less is the threshold for meeting the underweight criterion for AN in the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases 10).8,74 A BMI in the range of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2 is consistent with overweight, and a BMI higher than 30 kg/m2 reflects obesity.75

Expected weight for height = 100 pounds + 5 pounds per inch above 5 feet ± 10% for women, 106 pounds + 6 pounds per inch above 5 feet ± 10% for men and, if the patient is shorter than 5 feet, then the same number of pounds per inch is subtracted for each inch below 5 feet.76

Although this is a linear equation (compared with the quadratic equation for BMI) and may be less useful at extreme heights, it is straightforward to calculate. Moreover, conceptually, this formula may be easier for patients and families to understand, especially in setting weight goals or limits. A 90% to 110% range of expected body weight is considered within the normal range and is a good place to begin for setting weight gain goals for patients with AN. Within this range, the goal will be refined by clinical history (including the patient’s history of baseline, minimal and maximal weights), whether and when menses return, and medical parameters, such as reversal of bone loss. Patients below 85% of expected body weight likely meet the weight criterion for AN, and those below 75% of expected body weight are seriously nutritionally compromised and generally require inpatient care.77 For patients who are overweight or obese (>110% or >120% expected body weight, respectively), it may not be realistic or desirable to set weight goals within the normal range. Considerations in weight management are discussed subsequently.

Medical Evaluation

Medical evaluation includes a clinical history with special attention to weight fluctuations and any purging or other inappropriate behaviors to neutralize calorie intake to control weight (see Table 8-1). Ascertainment of syrup of ipecac use (as an emetic) and nonadherence to insulin protocols in patients with diabetes mellitus is essential, given the potentially lethal sequelae of these behaviors.78 Symptoms of medical complications of undernutrition, overnutrition, excessive exercise, or purging should be assessed and a menstrual history should be clarified. Physical examination includes a comprehensive assessment of potential complications of nutritional deficiencies, underweight, overweight, excessive exercise, and purging behaviors. If an eating disorder is suspected, physical examination may reveal signs to confirm nutritional compromise (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension, hypothermia, lanugo, breast tissue atrophy, muscle wasting, peripheral neuropathy) or to suggest chronic purging (e.g., Russell’s sign, an excoriation on the dorsum of the hand from chronic scraping against the incisors); hypoactive or hyperactive bowel sounds; an attenuated gag reflex79; dental erosion (perimolysis; Fig. 8-2)80; or parotid hypertrophy (Fig. 8-3).81

Figure 8-2. Dental erosions resulting from chronic vomiting.

(Adapted with permission from the Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.)

Figure 8-3. Patient with parotid hypertrophy resulting from chronic vomiting.

(Adapted with permission from the Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.)

Medical complications of behaviors associated with AN, BN, BED, and EDNOS are potentially serious and are too numerous to review in detail here; selected complications are listed in Table 8-3. Complications that are common and/or associated with serious morbidity should be actively sought on physical examination and laboratory studies, so that appropriate interventions can be initiated. Examples of such important and common findings include abnormal vital signs (e.g., hypotension, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia), low weight or overweight, osteopenia or osteoporosis,82 and dental pathology (e.g., perimolysis [erosion of the tooth enamel], caries, or both).81,83,84 Cardiac complications can be lethal and include prolonged QT interval, QT dispersion, ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiac syncope.85,86 Neurologic findings in AN include cortical atrophy and increased cerebral ventricular size.87 Endocrinologic abnormalities include menstrual abnormalities, low serum estradiol levels, low serum testosterone levels, hypercortisolism, and euthyroid sick syndrome, with resultant hypotension and cold intolerance.88 Reported complications of eating disorders during pregnancy include miscarriage, inadequate weight gain of the mother, intrauterine growth retardation, premature delivery, infants of low birth weight and low Apgar scores, and perinatal death.89–92

Table 8-3 Selected Clinical Features and Complications of Behaviors in Patients with Eating Disorders

| SYSTEM AFFECTED | Clinical Feature or Complication | |

|---|---|---|

| ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT LOSS AND FOOD RESTRICTION OR BINGE-EATING IN ANOREXIA NERVOSA | SSOCIATED WITH PURGING OR REFEEDING BEHAVIORS IN ANOREXIA NERVOSA, BULIMIA NERVOSA, OR EDNOS | |

| Cardiovascular | ||

birth weight infant)

EDNOS, eating disorder, not otherwise specified.

* Gastrointestinal complications associated with binge pattern eating in any of the eating disorders, are not all listed, and include weight gain, acute gastric dilatation, gastric rupture, gastroesophageal reflux, increased gastric capacity, and increased stool volume.

Laboratory Evaluation

Whereas choice of laboratory studies to evaluate medical complications of eating disorders will depend on the clinical history and presentation, it is useful to obtain serum electrolyte levels among individuals in whom AN or BN is suspected or confirmed. For example, hypokalemia occurred in 4.6% of a large sample of outpatients with eating disorders in one study93 and in 6.8% of individuals with BN in another moderately sized sample.94 In the latter study, hypokalemia was significantly more common in patients with BN than in those without BN. Although assessment for hypokalemia is not efficient for identifying occult cases of BN, it will assist in the identification and monitoring of individuals at risk for cardiac arrhythmias secondary to their eating disorder. Hypochloremia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and hyperphosphatemia also are seen in patients with eating disorders.88,94–96 In addition, for patients with AN, a serum glucose determination is recommended to identify hypoglycemia, which can be severe in this population.97 Although hyperamylasemia reportedly is common in BN (i.e., in 25% to 60% of cases), laboratory analysis of serum amylase generally is not clinically useful for detecting BN or gauging the severity of bingeing and purging symptoms.98 An elevated serum amylase level in a patient with AN or BN often reflects increased salivary isoamylase activity98,99; however, pancreatitis should be considered, when clinically appropriate, given its occurrence in this patient population. A complete blood count is recommended to assess for anemia, neutropenia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia among patients with AN. A retrospective study of 67 patients with AN found that 27% had anemia, 17% had neutropenia, 36% had leukopenia, and 10% had thrombocytopenia.100 Evaluation of the cause of amenorrhea is suggested, even if it is presumed to be related to decreased pulsatility of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secondary to weight loss.88 Menstrual irregularities are common among women with eating disorders, but women with symptomatic eating disorders still may be menstruating at presentation101 and women with AN can become pregnant102; a quantitative β-human chorionic gonadotropin and possibly a serum prolactin level therefore are recommended. Additional studies such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to evaluate ovarian function or neuroimaging studies to exclude a pituitary lesion may be indicated in some clinical scenarios.

Bone densitometry using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans of the hip and spine are useful in identifying bone loss and can be repeated after a year to assess further bone loss if disease continues. Osteopenia and osteoporosis may be present in as many as 90% and 40%, respectively, of women with AN, and are associated with risk of fractures and kyphosis.103,104 An electrocardiogram is recommended to evaluate patients with eating disorders because idiopathic QT prolongation can occur with AN,105 and QT intervals may be prolonged in those with BN and EDNOS, even in the absence of hypokalemia.106 Use of pharmacologic agents that can prolong the QT interval (e.g., olanzapine or desipramine), as well as purging that leads to hypokalemia, may further increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmia in this patient population. Abuse of ipecac may result in potentially fatal cardiotoxicity and arrhythmias.78

GASTROINTESTINAL ABNORMALITIES ASSOCIATED WITH EATING DISORDERS

GI signs and symptoms are common in those with eating disorders (Tables 8-3, 8-4). It has been asserted that the most dramatic changes in bodily function caused by AN are in the GI tract.107 There is also evidence that many individuals with eating disorders may present with a GI complaint prior to seeking treatment for an eating disorder. In one small retrospective study, 8 of 13 inpatients with eating disorders had sought care for a GI complaint, and 6 of them had sought such GI care before tending to their eating disorder.108 Several cross-sectional studies of hospital inpatients with eating disorders have suggested that 78% to 98% have GI symptoms.109–113 For example, constipation is a frequently reported symptom in AN and BN; in a study of 28 inpatients with an eating disorder, 100% of patients with AN and 67% of patients with BN had constipation.112 Nausea, vomiting, gastric fullness, bloating, diarrhea, and decreased appetite also are seen commonly in AN and bloating, flatulence, decreased appetite, abdominal pain, borborygmi, and nausea commonly are reported in BN. In one study of 43 inpatients with severe bulimia nervosa, 74% reported bloating, 63% reported constipation, and 47% reported nausea; borborygmi and abdominal pain also were more frequent than in the comparison group of healthy controls.110 Moreover, certain GI symptoms have been shown to be more common in dieters (specifically, abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea)114 and in those with binge eating (nausea, vomiting, and bloating) than in normal controls.115 A large study of obese individuals with GI symptoms found a strong association between BED and abdominal pain and bloating, after adjusting for BMI.116 Finally, a study of 101 consecutive women admitted to an inpatient eating disorders program found the vast majority of study participants (98%) to have functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Among these, 52% had irritable bowel syndrome, 51% had functional heartburn, 31% had functional abdominal bloating, 24% had functional constipation, 23% had functional dysphagia, and 22% had functional anorectal pain; 52% of respondents met criteria for three or more FGIDs. Whereas the authors found psychological predictors for several of the FGIDs, they were not associated with functional abdominal bloating or functional dysphagia in this study population.109

Table 8-4 Common Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients with Eating Disorders

Specific GI findings are commonly associated with eating disorders. Delayed whole-gut transit time98 and delayed gastric emptying appear to be common among inpatients with AN or BN.24,117–120 Delayed colonic transit has been reported in AN.121 Mild esophagitis is common (e.g., 22% of a case series of 37 consecutive patients) in patients with chronic BN, but more serious esophageal disease is rare.122,123 Abnormal esophageal motor activity has been reported in AN and BN.124,125 Barrett’s esophagus, Mallory-Weiss tears, and gastroesophageal reflux have been reported in association with chronic vomiting associated with BN.126 Unusual GI manifestations and catastrophic complications have been described in case reports of patients with eating disorders, including acute gastric dilation, gastric necrosis and perforation, and occult gastrointestinal bleeding (attributed to transient intestinal ischemia in the setting of endurance running).127–129 Rectal bleeding and rectal prolapse have been reported in patients with AN and BN.130,131

Other studies have found abnormal gastric function in patients with eating disorders, including diminished gastric relaxation (in patients with BN),132 bradygastria (in patients with AN, BN, and EDNOS),133 and higher gastric capacity (in patients with BN).134 Some evidence suggests that the GI abnormalities associated with eating disorders may be related to the duration or presence of active eating disorder symptoms. Physiologic sequelae of disordered eating, such as contracted or expanded gastric capacity, altered gastric motility, delayed large bowel transit (through reflex pathways),135 and possibly blunted postprandial cholecystokinin release, may perpetuate symptoms that exacerbate the excessive body image concern driving abnormal eating patterns.24 There is evidence that subjective reports of GI symptoms do not correlate well with physiologic data in patients with eating disorders.136

GI findings associated with eating disorders are listed in Table 8-3. In one study,137 elevated liver biochemical test results were documented in 4.1% of 879 patients presenting for treatment of an eating disorder. A probable cause distinct from the eating disorder was identified for 47% of the study participants but, for the remaining 53% of subjects, the abnormal results could not be attributed to a condition other than their eating disorder. Elevated enzymes were seen in underweight and normal-weight study participants. The results of this study suggest that abnormal liver biochemical tests are neither a specific nor a common marker for an eating disorder, and other possible causes should be excluded before attributing such abnormality to the eating disorder.137 In contrast, a study of 163 adolescent and young adult women outpatients with AN or EDNOS and low weight (excluding those with acute illness, alcohol abuse, hepatitis from viral or other known causes, and on medications associated with elevated liver enzyme levels) found elevated aminotransferase levels (alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase) in 19.6% of AN patients with a BMI lower than 16 kg/m2; 8.7% of AN patients with BMI higher than 16 kg/m2, and 15.2% of low-weight EDNOS patients.138 Elevated liver biochemical test results and hepatomegaly also are observed on the initiation of refeeding in AN.137,139 There also are several case reports of severe liver dysfunction or damage in patients with AN attributed to malnutrition and associated hypoperfusion.140–142

Although many of the common GI complications of eating disorders are relatively benign, others, such as acute gastric dilation, gastric necrosis, and gastric rupture,143–147 although uncommon, are serious or even catastrophic. Esophageal rupture is another potentially catastrophic risk with chronic vomiting.139 Acute pancreatitis has been reported in patients with AN and BN,145,148,149 and also can be associated with refeeding in AN.138 In addition, there is a case report of severe steatosis resulting in fatal hepatic failure in a patient with severe AN150 and one of death resulting from duodenal obstruction secondary to a binge in a patient with BN.151 Both help-seeking and diagnosis may be delayed or complicated by an undisclosed or unrecognized eating disorder.127,145,152 Conversely, esophageal dysfunction can be obscured by bulimic symptoms79,124 and can be misdiagnosed as AN.125 Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome can complicate AN and occurs when the support of the SMA is lost with weight loss and the duodenum is compressed between the aorta and the SMA. Because it manifests with vomiting, a concurrent diagnosis can be missed if this symptom is attributed to the eating disorder.153

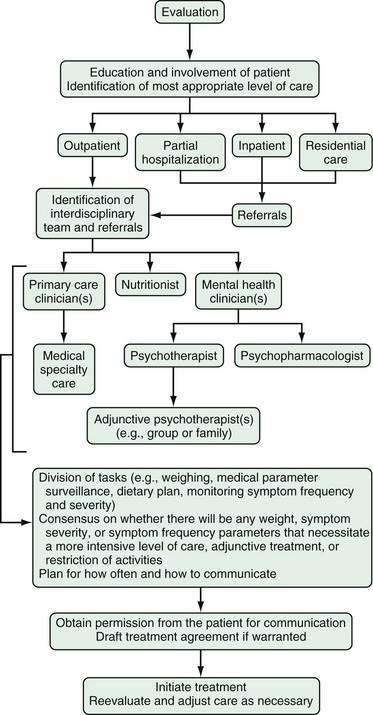

MANAGEMENT

Optimally, management of patients with eating disorders includes integration of mental health, nutrition, and primary care (Fig. 8-4). Occasionally, medical subspecialty consultation and care are helpful. Multidisciplinary management is desirable for several reasons. First, patients are at risk of medical, psychological, and nutritional complications of their disease. Second, patients commonly selectively avoid care essential to their ultimate recovery. For example, a patient may wish to avoid the detection of an injury so that she or he can continue to participate in a team sport; another may find it difficult to undergo the psychological work necessary to address antecedents of her illness; or another may wish to bypass active weight management. Conversely, a patient may attempt to pursue relief for specific medical complications to the exclusion of appropriate psychological or nutritional therapies.

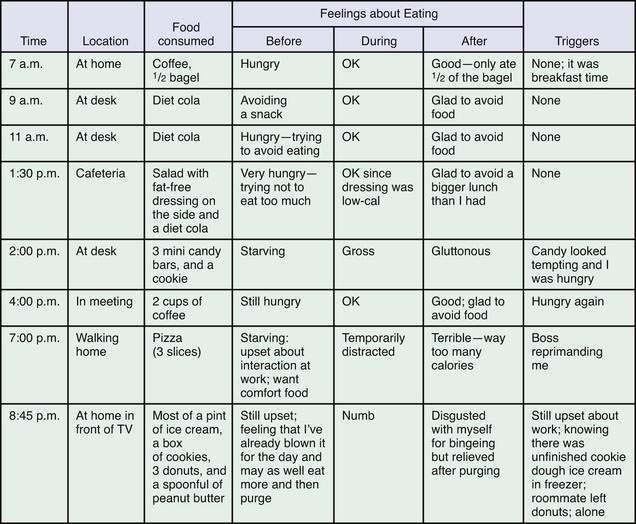

PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT

Psychiatric treatment generally begins with psychotherapy. In many cases, pharmacotherapy is useful as an adjunctive treatment for BN and BED. Active weight management is indicated for AN, and there is a role for weight loss treatment in some patients with BED. Usually, psychotherapy can be used to support weight management goals, although optimally it should be coordinated with the efforts of the nutritionist and primary care clinician on the team. Regardless of the mode of psychotherapy chosen, specific behavioral strategies directed at establishing normal eating patterns and drawing the patient’s attention to triggers for abnormal patterns can augment treatment. Among these, patients are encouraged to identify and avoid emotion-, schedule-, and food-related triggers to episodes of bingeing and to plan three regular meals and two between-meal snacks to prevent excessive hunger. Finally, a food journal (Fig. 8-5) kept for a few days and reviewed in a treatment session will help many patients identify relationships among psychosocial stressors, hunger, and symptoms and may provide a concrete framework from which to relate symptoms to other psychological concerns.

Psychotherapy

A variety of psychotherapies have established efficacy for the eating disorders. Recent guidelines and reviews have summarized findings from empirical studies and highlighted the paucity of recommendations for treatment of AN and EDNOS.77,154–157 Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) have received a great deal of research attention for the treatment of eating disorders. CBT is a structured, manual-based approach that addresses the relationships among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; IPT is another short-term therapy focused on present-day interpersonal events and roles in relationships. The choice of psychotherapeutic modality will be guided by the diagnosis, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, desirability of targeting the eating disorder symptoms versus broadening the therapeutic goals, treatment history, patient strengths and preferences, and the availability of care. Initial recommendations should be evidence-based when possible; however, clinical judgment is important for identifying individual needs and situations in which alternative treatment choices are appropriate.154 In practice, patients with AN or EDNOS can benefit from a flexible approach to treatment that uses appropriate components of the various therapeutic modalities because there is a dearth of empirical data to enable evidence-based recommendations and because some patients do not respond to evidence-based treatments.158

There is limited empirical evidence for AN treatments. The one consistent finding is that family therapy focused on parental control of nutrition emerges as the treatment of choice for adolescents, particularly those who are younger and who have a shorter duration of illness.155,159 Although evidence-based recommendations are limited, guidelines do suggest therapies to be considered for the psychological treatment of AN: cognitive analytic therapy (CAT), CBT, IPT, focal psychodynamic therapy and family interventions focused explicitly on eating disorders.154 A study comparing CBT, IPT and nonspecific supportive clinical management in the treatment of underweight AN outpatients found that the supportive treatment produced better global outcomes than IPT and was superior to CBT, over 20 weeks, in its impact on global functioning.160 The efficacy of CBT for underweight individuals remains unclear, but it appears useful as a posthospitalization treatment for AN, contributing to improved outcomes and relapse prevention in adults after weight restoration.161 Factors consistently predicting treatment outcome have not been identified.155

A number of treatments for BN have strong empirical support. CBT and IPT have been found effective, with CBT superior at reducing behavioral symptoms.156 CBT leads to faster improvement in symptoms, with better outcomes at the end of treatment, but at follow-up assessment there are no differences between CBT and IPT.162 All guidelines recommend CBT (16 to 20 sessions over four to five months) as the first-line treatment of choice for BN,77,154,156 but not all patients respond to CBT, and IPT is an effective alternative. CBT and IPT can be delivered in a group format as well as individually.163,164 Other promising treatment options with preliminary empirical support include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT, an approach developed for borderline personality disorder that focuses on assisting patients in developing skills to regulate affect165) and a manual-based guided self-change approach.166 For a subset of patients, self-help or guided self-help with an evidence-based CBT manual167 is an appropriate starting point for treatment in a stepped-care approach154 or if other treatments are not available.168 A variety of factors have been shown to be associated with treatment outcome in BN, but two emerge consistently—severity (higher frequency of binge eating) and duration of illness are associated with poorer outcomes.156

There are limited data to guide treatment decisions for the large proportion of individuals with eating disorders who are diagnosed with EDNOS. The main exception is the subgroup of those with BED. As with BN, some individuals will benefit from an evidence-based self-help program as a first step in treatment or if other treatments are not available.77,154,168 Studies have found that self-help intervention, delivered in a variety of ways (with varying levels of professional or peer support), leads to better outcomes when compared with control groups, with reductions in binge eating, binge days, and psychological features associated with BED (for a review, see Brownley and colleagues157 and Sysko and Walsh168). After consideration of self-help, American Psychiatric Association (APA)77 and National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)154 guidelines recommend CBT adapted for BED as an initial treatment choice. Group CBT has been found effective for treating binge eating in overweight individuals.169,170 There is some support for individually based CBT, although methodologic limitations preclude firm conclusions. Group IPT and adapted DBT are options to consider if CBT is not a good match for the individual or is unavailable. In one study, IPT was found to lead to similar abstinence rates as CBT at one-year follow-up.170 DBT has shown promising results, with a recovery rate of 56% at six months after treatment in one randomized controlled trial (RCT).171 It is important to note that treatments for BED usually do not result in weight loss, but they may still be of benefit with regard to weight by preventing further weight gain.157 This issue of dual treatment goals—weight loss and reducing binge eating—is explored in depth later in this chapter (see “Weight Management”). Further research is needed to establish and replicate factors associated with treatment outcome.

Across all diagnoses and treatments, there has been little attention to differential outcomes by socioeconomic factors. Future studies are needed to explore whether treatment efficacy differs by gender, age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or cultural group.155,156 Given the frequent psychiatric comorbidity associated with eating disorders, as well as psychosocial risk correlates, some patients with an eating disorder will benefit from psychodynamic psychotherapy and a flexible and eclectic approach depending on patient capabilities, goals, treatment history, and other psychosocial considerations.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacologic management has an adjunctive role for the treatment of BN and BED. Of numerous agents that have been studied, only one, fluoxetine, has U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for an eating disorder (bulimia nervosa). There is insufficient empirical support for efficacy of any agent in treating the primary symptoms of AN. Similarly, there are no clinical trial data to support recommendations for the pharmacologic management of EDNOS (with the exception of trials addressing BED and NES). Finally, there are not adequate available clinical trial data to support recommendations for pharmacologic management of eating disorders in children and adolescents.172

Among a variety of agents evaluated for treatment of the primary symptoms of AN, several have been studied because of their association with weight gain; of these, none is in routine clinical use. Although some data have suggested that olanzapine may be beneficial in promoting clinical improvement in AN,173,174 a recent RCT combining olanzapine with CBT versus placebo with CBT did not demonstrate significant between-group differences in improvement in BMI.175

Other agents may have a limited role in the management of AN but do not have FDA approval for this indication. Fluoxetine has not been found to be effective for treating the primary symptoms of AN in underweight patients176 and has unclear benefit in stabilizing weight-recovered patients with AN.177,178 Sertraline (50 to 100 mg/day) was associated with significant clinical improvements in a small, open, controlled trial of patients with AN.179 Comorbid psychiatric illness is common among patients with AN and may improve with pharmacologic management, but depressive symptoms in severely underweight patients may not respond as well to antidepressant medication as in normal-weight patients.

Notwithstanding the very limited role for psychotropic medication in the management of AN, patients likely will need calcium and vitamin D supplementation if dietary sources are inadequate.88 Although oral contraceptive agents may mitigate some of the symptoms of hypoestrogenemia associated with AN, they do not protect against bone loss in this population.150,180 It is useful for clinicians to bear in mind that weight restoration is the treatment of choice for underweight individuals with AN for medical stabilization, and probably also as a prerequisite to developing the psychological insight necessary for recovery.

In contrast to the limitations of medication management for AN, a number of medications have established short-term modest efficacy for the treatment of BN, although remission rates are low.181 CBT has better efficacy than medication to reduce the symptoms associated with BN, but there is some support for augmenting psychotherapy with medication, and this is fairly routine clinical practice. It is optimal to use pharmacotherapy as an adjunct to, rather than a substitute for, psychotherapy; psychotherapy, however, may not be available or beneficial to all patients. Some evidence supports treatment with fluoxetine (60 mg/day) alone in a primary care setting.182 Fluoxetine (60 mg/day) also has been found superior to placebo for treating bulimic symptoms in patients who have not responded adequately to CBT or IPT.183

Of medications with established efficacy in treating BN, only fluoxetine has FDA approval for this indication. Fluoxetine (60 mg/day) generally is well tolerated in this patient population and has been shown to be effective for symptom reduction and for maintenance therapy for up to 12 months.184,185 Desipramine and imipramine (both at conventional antidepressant dosages, as tolerated) also have efficacy in symptom reduction, but are not as well tolerated in this patient population.186 Topiramate has shown efficacy in reduction of binge and purge symptoms in two short-term RCTs in individuals with BN.187–189 Other agents that have demonstrated at least some efficacy (but with less data available) are trazodone,190 ondansetron (in patients with severe BN),191 and sertraline.192 Flutamide has shown some efficacy in reducing binge (but not purge) frequency in one small RCT, but was associated with hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity and cannot be recommended for the treatment of BN.193 A number of studies has investigated the efficacy of naltrexone in treating bulimic symptoms,186 but only at higher doses was it superior to placebo and in reducing symptoms in patients who had previously not responded to alternative pharmacotherapy.194 Monitoring of liver biochemical test results is essential when this drug is used. Other medications with efficacy are relatively contraindicated for those with BN given their potential adverse effects. For example, bupropion was associated with a seizure risk of 5.8% during a clinical trial195 and there have been case reports of spontaneous hypertensive crises in patients with BN who were taking monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors.196 Finally, although fluvoxamine has shown some efficacy for BN relapse prevention in one RCT,197 another RCT combining fluvoxamine with stepped-care psychotherapy not only did not show efficacy of this agent, but also reported grand mal seizures in participants on the active drug.198

Several trials have investigated the efficacy of pharmacologic treatment of BED. Of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), sertraline,199 fluvoxamine,200 citalopram,201 and fluoxetine202 have shown some efficacy in reducing symptoms associated with BED in RCTs. In addition, atomoxetine,203 orlistat in combination with CBT,204 and zonisamide205 have shown efficacy in an RCT, although zonisamide was not well tolerated in this BED study population and significantly greater binge remission rates in the orlistat group were not maintained at the three-month post-treatment follow-up.206 Two agents, sibutramine207 and topiramate,208 have shown efficacy in reducing symptoms of BED (the latter in BED co-morbid with obesity) in multisite placebo-controlled trials. None of these medications has FDA approval for the treatment of BED. Notwithstanding some efficacy of medication, studies have suggested that CBT is a superior treatment and that augmentation of CBT with medication may not enhance treatment response.209

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Active weight management is a cornerstone of treatment for AN. As essential as weight gain is to reduce or reverse the medical and cognitive sequelae of severe undernutrition, it is one of the great challenges in the successful treatment of this illness. By definition, individuals with AN are unreasonably fearful of gaining weight and many of them remain unconvinced of the serious medical impact of their self-starvation. Ideally, patients can be engaged in the process of weight recovery by identifying some clear benefit (e.g., permission to remain on an athletic team or participate in a performance, or to avoid a compulsory medical leave from school or work). Such behavioral reinforcement can be an essential adjunct to a nutritional plan that provides balanced nutrition and calories adequate for weight gain and reestablishes routine meals. Outpatient weight recovery is best addressed with the collaboration of a nutritionist experienced in the treatment of AN. As calories are added and foods are reintroduced into the diet, patients may initiate or increase compensatory behaviors (e.g., exercise, purging) to control weight gain. If possible, behavioral restrictions on exercise can be implemented if patients are not meeting weight gain goals. Caloric supplements often are added as snacks to help patients meet nutritional and weight gain goals. Patients with early satiety and delayed gastric emptying have a particularly difficult time adding calories because gastrointestinal discomfort and bloating enhance their concerns about feeling and being “fat.”210,211

Severely malnourished patients—especially those below 70% to 75% of expected body weight—require inpatient care for refeeding. Patients with AN are at particularly high risk of refeeding syndrome, which can occur with any means of refeeding (see Chapters 4 and 5).212 Refeeding syndrome, typically associated with hypophosphatemia in the setting of depletion and cellular shifts in the early weeks following refeeding, can result in delirium, congestive heart failure, and death.213 Risk for refeeding syndrome can be reduced for at-risk patients by using an initially low-calorie prescription that is advanced slowly. During at least the first two weeks of refeeding, serum electrolyte, phosphorus, and magnesium levels should be monitored closely (e.g., six to eight hours after feeding begins, then daily for a week, then at least every other day until the patient is stabilized214). Heart rate, respiratory rate, lower extremity edema, and signs of congestive heart failure also should be evaluated daily for at least a week and then gradually at longer intervals as the patient stabilizes, and cardiac telemetry should be used to monitor heart rhythm during the first two weeks so that supplementation and other appropriate measures can be instituted if hypophosphatemia or other signs of refeeding syndrome develop. Delirium may occur in the second week of refeeding, or later, and may last for several weeks.215–218

Some experimental data have suggested that a healthful dieting intervention may be beneficial in reduction of bulimic symptoms219 but, conventionally, weight loss treatment has been discouraged in patients with BN because dieting can stimulate bingeing and purging. Weight loss is often a primary or secondary treatment goal for individuals with BED because of comorbid obesity. Models of binge eating have proposed that dietary restriction is an antecedent to binge eating; thus, there has been debate about the optimal means and order of addressing co-occurring binge eating and obesity. Most data, however, have shown that a variety of weight loss approaches do not exacerbate binge eating and may help reduce symptoms; one prospective study found no evidence that a reduced calorie diet precipitated binge eating in women with obesity.220 Behavioral weight loss treatment (BWLT)221 and very low-calorie diets (VLCDs)222,223 have been found effective for reducing symptoms of BED. Available evidence also supports that CBT and BWLT are equally effective in terms of binge eating outcomes, although the rates of change differ for binge eating and weight loss. Binge eating decreases faster with CBT, whereas weight decreases more rapidly with BWLT, so treatment priorities may inform recommendations. The addition of exercise to treatment for BED is associated with greater decreases in binge eating and BMI.224 Although a number of studies have found that treating binge eating does not translate to weight loss, some studies have found that reductions in binge eating can assist in modest weight loss among those with BED, especially when complete remission is achieved.225

BED is common in individuals presenting for obesity surgery, so there is much interest in clarifying how BED affects the outcome of bariatric surgery and, conversely, how surgery might influence binge eating behavior. The prevalence of BED in preoperative gastric bypass patients has been found to range from 2% to 49%, and up to 64% of bariatric surgery candidates have binge eating behaviors.226 The most current studies examining presurgery binge eating, postsurgery binge eating, and long-term weight outcomes suggest that a presurgery history of binge eating does impart risk for poorer long-term weight outcome.226,227 Postsurgical binge eating usually is seen in patients who reported binge eating prior to surgery and is rare among those without presurgery binge eating.226 Patients who continue to experience binge eating after surgery have poorer weight outcomes. One study has shown that a history of binge eating before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is associated with significantly less weight loss at one- and two-year follow-ups.227 Many patients with binge eating will have positive outcomes after bariatric surgery, but adjunctive treatment is likely to be important for optimizing outcomes and preventing relapse.

There are few data on bulimia or self-induced vomiting and bariatric surgery. Cases of AN developing after bariatric surgery have been reported.228,229

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL SYMPTOMS OF PATIENTS WITH EATING DISORDERS

Individuals with eating disorders are likely to have co-occurring GI symptoms for which consultation may be sought. GI complaints are the most common somatic complaint among adolescents with partial eating disorders.230 Similarly, childhood GI complaints may influence later risk or timing or onset and severity for an eating disorder. In some cases, behaviors associated with eating disorders result in serious GI complications. In other cases, GI symptoms may be mild and not correlate with underlying pathology, but may compromise efforts to nutritionally rehabilitate the patient. Given the evidence that restrictive eating, binge pattern eating, and purging behaviors may underlie or exacerbate some of the GI symptoms, concurrent management of the eating disorder is integral to prevent worsening of the GI manifestations of illness. Careful differential diagnosis also is necessary to avoid misattribution of symptoms to an eating disorder and to detect primary GI pathology that may be obscured by an eating disorder. Available data suggest that individuals with an eating disorder are significantly more likely to seek GI specialty care than healthy controls.53 Moreover, presentation to a GI practice rather than to an eating disorder specialty practice results in delayed diagnosis and a greater number of clinical tests than controls with slow transit constipation.56 Because the GI consultation may precede help-seeking related to the primary symptoms of the eating disorder, the patient’s care will benefit from identification of an associated eating disorder, evaluation of its severity, and appropriate counsel about the necessity of team management and referrals to mental health, nutritional, and primary care clinicians. A case series of individuals with coexisting comorbid eating disorders and celiac disease has illustrated how synchronous GI and eating disorders reciprocally influence management. For example, celiac disease can mimic, exacerbate, or promote recovery from an eating disorder, whereas an eating disorder can reduce adherence to treatment for celiac disease.57

Subjective reports of Gl symptoms may not reliably indicate pathology122,231; moreover, they may be mediated by affect103 or body image concerns.93 Thus, when patients complain of bloating and constipation, it is useful to determine to what extent these complaints stem from fear of gaining weight or reflect decreased GI motility.

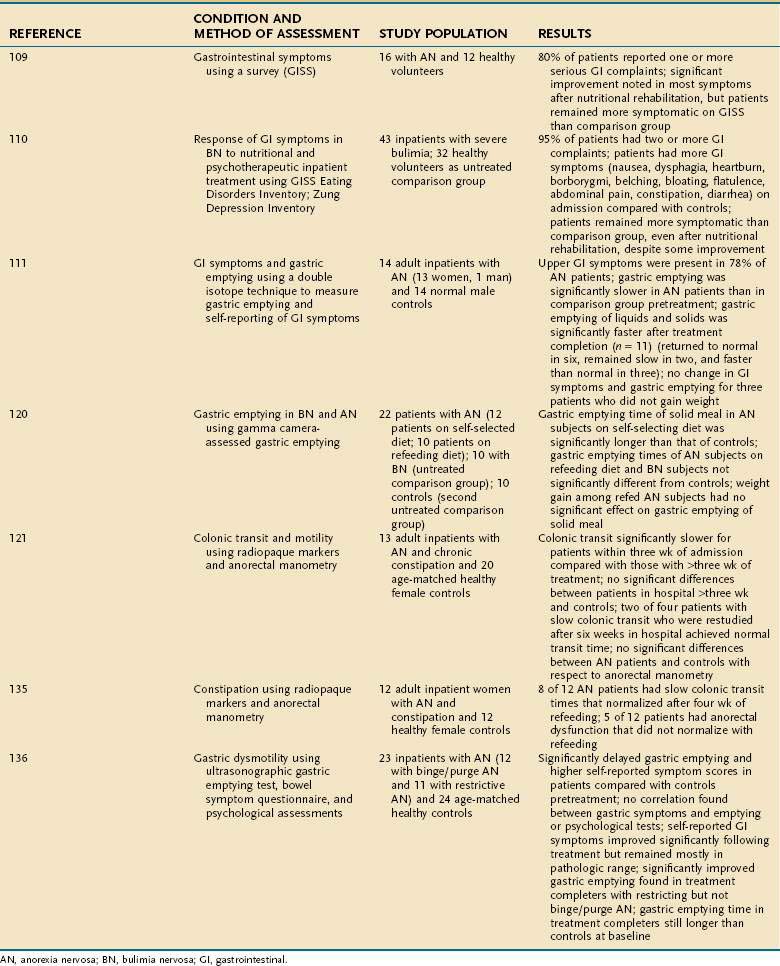

A number of studies have evaluated improvement in GI function after nutritional rehabilitation (Table 8-5). These studies have yielded mixed results, and conclusions have been limited by small sample sizes and nonrandomized design. For example, in one study,122 gastric emptying improved in patients with restricting type AN, but did not improve in patients with binge eating–purging type AN after a 22-week treatment period of increasing dietary intake up to 4000 cal/day and CBT. Self-reported GI symptom scores improved after treatment in this same study, but remained abnormal and did not correlate with gastric emptying as evaluated with ultrasound.122 Another study of a mixed sample of adolescents and adults with AN did not demonstrate significant improvement of gastric emptying after weight gain (N = 6), despite normalization of heart rate and blood pressure.232 Other studies have suggested that nutritional rehabilitation is associated with improved gastric emptying in inpatients with AN, but it is unclear whether such improvement is related to refeeding per se, or to weight gain.97,122,106,233 Constipation is a frequent complaint of patients with AN and BN and may have multiple causes. Colonic transit appears to be delayed in patients with constipation and AN, but colonic transit has been shown to return to normal within three to four weeks of refeeding in hospitalized patients with AN.107,121 In one study, however, anorectal dysfunction in anorexic patients with severe constipation did not significantly improve with refeeding. The investigators suggested that abnormal defecatory perception thresholds and expulsion dynamics in AN may have contributed to the patients’ unremitting constipation.121 Laxative abuse occurs in AN234 and BN.235 Some patients use laxatives as their chief method of purging and may gradually escalate their daily dose to very large amounts. Although the relationship of laxative abuse to colonic dysfunction remains controversial,236–238 it has been observed that patients with chronic laxative abuse complain of constipation while tapering off their laxatives. Rectal prolapse has been described with AN and BN and is thought to be linked to constipation, laxative use, excessive exercise, and increased intra-abdominal pressure secondary to self-induced vomiting.116,117

Table 8-5 Selected Studies of Effects of Nutritional Rehabilitation on Gastrointestinal Symptoms Associated with Eating Disorders in Adults

Because refeeding and establishing normal and healthful dietary patterns are both treatment goals and likely to improve symptoms, careful nutritional rehabilitation is a reasonable and conservative initial step in management of suspected delayed gastric emptying and slow colonic transit for inpatients with AN or BN. Patients are likely to benefit from the support and reassurance that many of the GI symptoms commonly associated with eating disorders (e.g., bloating, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) will improve as eating and weight return to normal. Additional management strategies include dietary changes to reduce bloating (e.g., promoting smaller, more frequent meals, encouraging consumption of liquids earlier in the meal, and possibly providing a percentage of calories, no more than 25% to 50%, in liquid form initially).58,95

Various prokinetic agents have been used to manage delayed gastric emptying in AN, although metoclopramide is difficult to tolerate in frequent or high dosage, domperidone is not available in the United States except in compounding pharmacies, and cisapride is no longer being manufactured. Moreover, existing data do not support a recommendation for their use for gastric motility complaints in AN.211

Some clinicians have reservations about treating the constipation that follows laxative abuse with laxatives. Although it does not make sense to reproduce purging behavior using cathartics to treat constipation in patients with chronic laxative abuse, some patients will benefit from a thoughtful bowel regimen to reduce discomfort and bloating that otherwise might induce relapse of laxative abuse. Increasing fluid intake, dietary fiber, and possibly the addition of stool softeners and bulk-forming laxatives would be reasonable and conservative initial treatment. Osmotic laxatives initially may be necessary for symptom relief in some cases.239 Management of constipation may require anorectal retraining if a result of anorectal dysfunction.121

Some patients may benefit from symptomatic relief of gastroesophageal reflux or esophagitis with antacids or H2 antagonists; proton pump inhibitors may be required for relief of more severe symptoms.58 Although this may be appropriate clinically, the underlying cause and exacerbation of the GI complaint should be made clear to the patient and also actively addressed in psychotherapeutic treatment when related to the eating disorder. Mild elevation of serum aminotransferase levels secondary to malnutrition in AN likely will likely remit with weight restoration. Elevated serum levels of liver enzymes in severely ill patients may be an indication of refeeding syndrome or reflect AN-related hypoperfusion, and require emergent evaluation and intervention.58,128

Although many GI symptoms may be related to restrictive eating, binge pattern eating, or purging, some GI complaints will require diagnostic evaluation. Anecdotal reports of catastrophic GI complications of the eating disorders, as well as primary GI illness that arises coincidentally with an eating disorder or mimics an eating disorder, suggest that complaints should be evaluated in their specific clinical context. Acute gastric dilation may be unsuspected in the absence of clinical history of binge eating.130 If acute gastric dilation is confirmed in the setting of refeeding or in the presence of a history of an eating disorder with binge eating, nasogastric decompression and fluid resuscitation are necessary. If these are not effective, laparotomy may be necessary.113,114,130 In addition, symptoms that persist after nutritional rehabilitation may require additional diagnostic evaluation.

American Psychiatric Association. Treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(Suppl):4-54. (Ref 77.)

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. (Ref 8.)

Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Sedway JA, et al. Binge eating disorder treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:337-48. (Ref 157.)

Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Anorexia nervosa: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:310-20. (Ref 155.)

Emmanuel AV, Stern J, Treasure J, et al. Anorexia nervosa in a gastrointestinal practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1135-42. (Ref 56.)

Hadley SJ, Walsh BT. Gastrointestinal disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2003;2:1-9. (Ref 211.)

Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11-53. (Ref 1.)

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HGJr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348-58. (Ref 3.)

Keel PK. Purging disorder: Subthreshold variant or full-threshold eating disorder? Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S89-94. (Ref 69.)

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Eating disorders—core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. NICE Clinical Guideline No 9. London: NICE; 2004. (Ref 154.)

Niego SH, Kofman MD, Weiss JJ, Geliebter A. Binge eating in the bariatric surgery population: A review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:349-59. (Ref 226.)

Shapiro JR, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, et al. Bulimia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:321-36. (Ref 156.)

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, May A, et al. Should night eating syndrome be included in the DSM? Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:544-9. (Ref 65.)

Winstead NS, Willard SG. Gastrointestinal complaints in patients with eating disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:678-82. (Ref 53.)

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992. (Ref 74.)

Zerbe K. Integrated treatment of eating disorders. New York: WW Norton; 2008. (Ref 158.)

1. Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11-53.

2. Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:389-94.

3. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HGJr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348-58.

4. Machado PP, Machado BC, Goncalves S, Hoek HW. The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:212-17.

5. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. YRBSS youth online: Comprehensive results. Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss/SelQuestYear.asp?Loc=XX&cat=5, 2009.

6. Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm F-A, Hook JM, et al. Night eating syndrome in young adult women: Prevalence and correlates. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:200-6.

7. Stunkard A, Allison KC. Two forms of disordered eating in obesity: Binge eating and night eating. Int J Obes. 2003;27:1-12.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

9. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Review of nocturnal sleep-related eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;15:343-56.

10. Jacobi C. Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, de Zwaan M, Steiger H, Mitchell J, editors. Eating disorders review. Part I. Chicago: Academy for Eating Disorders; 2005:59.

11. Becker AE, Fay K. Socio-cultural issues and eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, de Zwaan M, Steiger H, Mitchell J, editors. Annual review of eating disorders. Chicago: Academy for Eating Disorders; 2006:35.

12. Mazzeo SE, Slof-Op’t Landt MCT, van Furth EF, Bulik CM. Genetics of eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, de Zwaan M, Steiger H, Mitchell J, editors. Annual review of eating disorders. Chicago: Academy for Eating Disorders; 2006:17.

13. Fairburn CG, Welch SL, Doll HA, et al. Risk factors for bulimia nervosa: A community-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:509-17.

14. Fairburn CG, Doll HA, Welch SL, et al. Risk factors for binge eating disorder: A community-based, case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:425-32.

15. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, Schwartz D, Thompson M. Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychol Rep. 1980;47:483-91.

16. Striegel-Moore RH, Silberstein LR, Rodin J. Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. Am Psychol. 1986;41:246-63.

17. Polivy J, Herman CP. Etiology of binge-eating: Psychological mechanisms. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993:173.

18. Gendall KA, Joyce PR, Carter FA, et al. Childhood gastrointestinal complaints in women with bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:256-60.

19. Bailer UF, Frank GK, Henry SE, et al. Serotonin transporter binding after recovery from eating disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2007;195:315-24.

20. Kaye W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:121-35.

21. Philipp E, Pirke K, Kellner MB, Krieg J. Disturbed cholecystokinin secretion in patients with eating disorders. Life Sci. 1991;48:2443-50.

22. Tomasik PJ, Sztefko K, Starzyk J. Cholecystokinin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide and glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion in children with anorexia nervosa and simple obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2004;17:1623-31.

23. Baranowska B, Radzikowska M, Wasilewska-Dziubinska E, et al. Disturbed release of gastrointestinal peptides in anorexia nervosa and in obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2000;2:99-103.

24. Devlin MJ, Walsh BT, Guss JL, et al. Postprandial cholecystokinin release and gastric emptying in patients with bulimia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:114-20.