Chapter 1 Eastern Origins of Integrative Medicine and Modern Applications

Introduction

Introduction

Terminology

As the field of integrative medicine evolves, so does its terminology. “Modern medicine” in this chapter is used to describe the most mainstream medicine practiced and determined by the evolving scientific method, and “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) is used to describe practices that are not as well defined by the scientific method. Theories of medicine can also be grouped based on geographic origin: Western, originating from Greco-Roman philosophy, and Eastern, originating from Asian-Pacific philosophy. The term modern medicine implies fluidity, and it is fitting to use such terminology during the current period of expanding medical boundaries.

Comparison of Eastern and Western Medicine: Origins and Philosophies

Comparison of Eastern and Western Medicine: Origins and Philosophies

Historical Origins

It was not until later in the twentieth century, however, that the scientific method became the mainstay of modern medicine. In the early nineteenth century, modern medicine was pluralistic in nature as “professional care was mostly provided by botanical healers and midwives, supplemented by surgeons, barber-surgeons, apothecaries, and uncounted cancer doctors, bonesetters, inoculators, abortionists, and sellers of nostrums.”1 During much of this same period, the profession of naturopathy flourished to the benefit of many. At this time, the medical profession was still in its early stages in the United States. By the early to mid-twentieth century, medicine was much more narrowly defined through the scientific method. In the past 20 years, however, medicine in the United States has experienced another shift, arguably a shift again to the medical pluralism from more than 100 years ago. This raises the question: is this merely historical pattern or the birth of a unique era?

If modern medicine is experiencing yet another paradigm shift, the culture will necessarily move beyond the older ethos of the scientific method that defined its previous paradigm. Master Hong succinctly commented on this point, “What this [Qi Gong] master possesses isn’t magic. It is just science that has not yet been examined.”2 In the twenty-first century, the culture of medicine is once again embracing its diverse options for health care, shifting yet again toward pluralism and reflecting the social landscape of a new generation. What is happening invites all healers to enlarge their ideas of disease and health and to welcome an expanded and deeper perspective.

Philosophies in Contrast

“Vive la différence.” The differences in Eastern and Western medical traditions stem directly from their foundational differences in world views. Judith Farqhuar described these essential differences in world views as “the difference between a world of fixed objects and a world of transforming effects. Like the solid inertial world of modern natural science traditions, the … transformative world of Chinese medicine seems to exist prior to all argument, observation, and intervention. Perhaps with a certain discomfort, Western readers must acknowledge that ‘their’ abstractions about such things make as much sense as ‘ours’.”3

In its extreme, the patient is an accident attached to the disease under treatment.

These distinct differences shape the patient–doctor relationship. In Eastern traditions, a unique balance of these factors is critical to diagnosis and treatment of a patient’s disharmony rather than disease. Physicians in Western medicine often look beyond the patient–doctor relationship to an external body of knowledge to diagnose and treat, guided by categories of symptoms. A general comparison of Eastern and Western concepts with regard to health is shown in Table 1-1.

| WESTERN | EASTERN | |

|---|---|---|

| World views | Reductionist | Holistic |

| Mechanism of disorder | Pathologic mechanism | Imbalance of harmonies |

| Foundational structure | Logic, mathematics | Eastern religions and philosophies |

| Patient–doctor relationship | Access external body of knowledge for diagnosis and treatment | Unique balance critical to diagnosis and treatment |

Overview and Comparison of Eastern Traditions

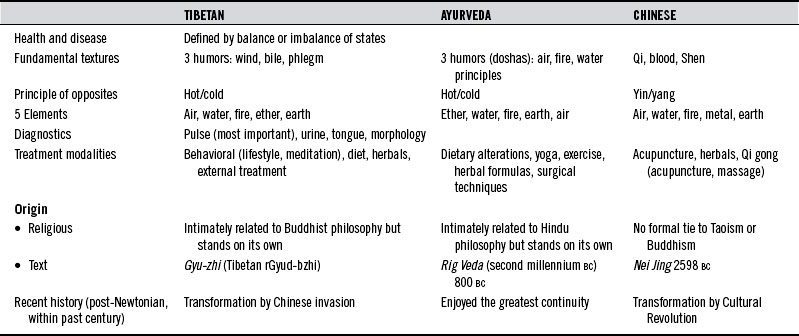

As mentioned, although several indigenous healing traditions in the East have been preserved, Chinese, Ayurvedic, and Tibetan medicine remain among the most heavily practiced traditions in their respective regions. All three traditions stem largely from similar philosophical foundations; thus in all, health and disease are seen as inextricably interrelated. They play integral parts in the delicate balance of harmony and disharmony. Table 1-2 provides a comparison of these three traditions.

Origins

Tibetan medicine and Ayurvedic medicine have similar historical origins, since Ayurveda is the root of Tibetan medicine. Ayurvedic origins are found as early as the second millennium BC in the Rig Veda, with its second classical stage in the Brahmanic period in 800 BC, where it continued as an unbroken lineage until the Moslem conquest of India in the thirteenth century. During that time in the sixth century BC, the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, was born in India, and after achieving Enlightenment under a Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya and delivering the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, Buddhism was born.*

The Tibetan medical tradition offers that the Buddha, often called the “Great Physician,” taught the medical texts himself, including the Gyu-zhi, the most important Tibetan medical text. The Sanskrit version of the Gyu-zhi, however, was probably not written until around 400 AD.4 Although some scholars may debate whether the historical Buddha’s teachings are the precise origin of Tibetan and, thus, Ayurvedic medicine, Buddhism’s influence on these two healing traditions is unquestionable.

Like Ayurveda, the origins of Chinese medicine date back to at least the second millennium BC, to the era of the great Yellow Emperor, Huangdi (2698–2598 BC). The classic medical text written during his reign is Huangdi Nei Jing (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon). Yet perhaps of more influence to Chinese medicine known today is the Nan Jing (The Classic of Difficult Issues), written around the first or second century AD. As Nolting notes in Chapter 31 on “Acupuncture” in this edition, the Nei Jing deals more with “demonological medicine and religious healing,” whereas the Nan Jing developed Chinese medicine as an original system, with well-defined and organized principles, diagnostics, and therapeutics.5

Chinese medicine also witnessed various transformations, most notably its recent evolution into Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the modern form of Chinese medicine practiced in China and worldwide. Influenced by the advent of modern science, Chinese medicine was required during the 1950s to establish increased legitimacy in the face of the new Marxist ideology, which emphasized “natural science” and delegitimized Confucian influences. Initially, the People’s Republic of China denounced folk, demonic, and Buddhist temple medicine.6 However, in 1951, Mao Zedong revived and then canonized portions of the tradition with his “Chinese medicine is a great treasure-house” speech.7 In Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Chinese medicine was transformed to TCM and embraced as a means to preserve the “spirit of a nation.” The “new medicine” movement highlighted traditional medicine’s ability to arouse one’s own bodily defenses against illness while excluding metaphysical ideologies. TCM thus embodied one general theory of Chinese medicine and discouraged diverse readings and interpretations by practitioners and students.

Despite its isolation in practice, Tibetan medicine shares several principles with other Eastern healing traditions. Its strongest ties are with Chinese medicine to the north and Ayurvedic medicine to the south. Eastern traditions of healing are undoubtedly intertwined in a rich tapestry, stemming partly from an extraordinary meeting of healers. During the seventh century, the Tibetan King Gampo held the world’s first recorded international medical conference. Noted physicians from India, China, Greece, Nepal, Persia, and Mongolia dialogued in a cross-cultural exchange, and texts from each medical tradition were translated.

Fundamental Philosophies: Tools to Assess Balance

In Ayurvedic medicine, these humors are the three Doshas, known as Vat (or air principle), Pit (or fire principle), and Kaph (or water principle), and they carry specific actions. Vat is the bodily air principle and governs movement; Pit is the bodily fire principle that controls metabolism; and Kaph is the biological water principle that provides physical structure. These principles are also associated with the metabolic activities of anabolism, catabolism, and metabolism. In addition, they are associated with certain personalities and certain physical characteristics of dry or oily, light or heavy, and hot or cold. For a more complete discussion of the Doshas and their related properties and functions, see Chapter 32.

Modern Applications: The Age of Integration

Modern Applications: The Age of Integration

As the social landscape changes, the culture of medicine continually redefines what is considered “conventional.” Numerous recent studies have shown that since the early 1990s, consumers have been demanding alternatives to modern care.8 Only since then has integrated medicine, including naturopathy, penetrated the Ivory Tower and research institutions in the United States. Driven by scientific advancement and a need for increased knowledge, this movement toward more pluralistic medicine has now brought us beyond the age of information and into the “age of integration.”

With the current plethora of health information, it is becoming more apparent that optimal healing is not the property of any one tradition or system. Integrative clinics that incorporate multiple healing systems now thrive throughout the country and at major academic medical institutions. Employers and managed care agencies are beginning to offer coverage for acupuncture, chiropractic, naturopathy, and massage services. The Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine has been formed among top-ranked medical schools to integrate CAM into their curricula. The National Institutes of Health has devoted an institute just for CAM with a budget of over $130 million.* Some medical residencies now include CAM in their training, and fellowships in integrative medicine now exist.

Tools for Integration

Tools for Integration

As providers of CAM services join professional networks and become increasingly integrated into conventional health delivery, the CAM professions gain both credibility and exposure. Integration brings with it a new set of responsibilities. Utilization is growing and evolving so quickly that the educational institutions preparing CAM providers for licensure are hard pressed to keep up with the trend. As a result, CAM provider education often does not fully prepare its graduates to meet the growing expectations of the public, the medical community, or the legal system. Providers must gain competency in “tools for integration” that lead to a new set of skills for clinical practice, risk management, professional communications, practice management, and research. These tools include, but are not limited to, those listed in Box 1-1.

1. Kaptchuk T., Eisenberg D. Varieties of healing. 1: Medical pluralism in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:189.

2. Liu H., Perry P. The healing art of Qi Gong: ancient wisdom from a modern master, (contributor). New York: Warner Books. 1999. 6

3. Farquhar J. Knowing practice: the clinical encounter of Chinese medicine. In: Kaptchuk T., ed. The web that has no weaver: understanding Chinese medicine. 2nd ed. Chicago: Contemporary Books; 2000:67.

4. Rechung R., Kunzang J. Tibetan medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1973. 3

5. Acupuncture Nolting M. Pizzorno J., Murray M. Textbook of natural medicine, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone. 1999:254.

6. Unschuld P. Medicine in China: a history of ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. 250

7. Farquhar J. Re-writing traditional medicine in post-Maoist China. In: Bates D., ed. Knowledge and the scholarly medical traditions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995:251.

8. Eisenberg D., Davis R., Ettner S., et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575.