36 Easing Distress When Death is Near

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heaped for the beloved’s bed;

What is a good death? When asked, many adults facing the end of life hope to control pain and other distressing symptoms, have a sense of preparation for death, and achieve a sense of completion; however, other factors important to quality at the end of life differ by the individual.1 For some, a child’s death can never be good. Nevertheless, as palliative care clinicians, we can aspire to enable a better death experience for the child and family when we are faced with the inevitability of a child dying. This chapter will review strategies aimed at trying to achieve this outcome.

Importantly, when a child is dying, all care goals may not be uniformly focused on easing suffering. Recent studies affirm the common clinical experience that even when a child’s illness is said to be incurable, parents will hope to extend life concurrent with ensuring comfort.2,3 Family values will differ: While some aspire for a peaceful end of life experience for their child, others value another approach, as stated by one father:

“The battle with the dragon, or the intent and the need, or the struggle to come to grips with him, or just coexist with him even, threatened to consume our lives. In the sense that the battle against the illness and all the circumstances—logistical and practical, and medical, and financial, and interpersonal…that became all consuming, just like the dragon’s fiery breath…just like his fiery breath is understood to be all consuming, literally obliterating either an individual, or a number of individuals, or a whole village.”4

Interdisciplinary Caring

During this most intimate of clinician-family experiences, the care of a dying child, exquisite collaboration among all involved is required to meet the needs of the child and family. Table 36-1 highlights key roles and activities of the interdisciplinary team. No matter where the child is being cared for, short huddles or meetings among team members may be helpful to maintain open lines of communication.

TABLE 36-1 Interdisciplinary Roles in the Care of the Imminently Dying Child

| Clinician | Discipline specific roles | Interdisciplinary roles |

|---|---|---|

Recognizing When Death Is Imminent

Dying is a dynamic process. Though the process is influenced by many factors, it is remarkable how similar it can be despite very different underlying illnesses. Clinical experience suggests that when approaching death, a child typically experiences the following constellations of findings. The child is often bedridden, semiconscious, with little or no oral intake, and changes in pulse, respiration and peripheral circulation may also be apparent (Box 36-1).5

BOX 36-1 Signs of Impending Death

Adapted from Bicanovsky L. Comfort Care: Symptom Control in the Dying. In Walsh, D et al Palliative Medicine 1st Edition, Saunders, An imprint of Elsevier Science, 2009.

Brain death

Typical signs of dying may not be present when a child is brain dead and is still receiving cardiorespiratory support. In children, brain death most commonly arises from traumatic brain injury due to child abuse, motor vehicle accidents, or asphyxia.6 Though there is general acceptance of the definition of brain death, it may still be difficult for parents and other loved ones to grasp this reality because the child may not appear dead. The clinical neurological examination remains the standard for the determination of brain death and has been adopted by most countries. The declaration of brain death requires not only a series of careful neurologic tests but also the establishment of the cause of coma, the ascertainment of irreversibility, the resolution of any misleading clinical neurologic signs, the interpretation of the findings on neuroimaging, and the performance of any confirmatory laboratory tests that are deemed necessary (Box 36-2).6 Despite medical consensus of the definition of brain death, not all religions officially accept this definition of death.7 Depending on the family’s beliefs and those of spiritual or religious advisers, families rarely disagree with this death pronouncement but conflict resolution may require ethics consultation and/or judicial involvement. Nonetheless, a thorough understanding of brain death can aid in conversations with families. Once cardiorespiratory support is discontinued, the typical signs of dying ensue.

Key communication topics

Several communication topics are discussed in detail in Section 2, and will therefore not be covered in this chapter. Notably, however, anticipatory guidance can help prepare families for the child’s end-of-life course and ease the child’s and family’s distress. Proposed timing for key communication topics in children with advanced life-threatening illness is as follows:

There are several key principles in managing the child’s final days. An analytical approach to symptom control continues, but usually relies on clinical findings rather than investigation. Drugs should be reviewed with regard to need and route of administration. Some patients manage to take oral drugs until near their death, but many require an alternative route. Finally, it is essential that the care team maintains effective communication and ensures that support is in place for the family. A daily visit for inpatients or a daily phone call at a planned time can be very reassuring for families. Experience suggests that clinician home visits from the hospital-based team are greatly appreciated throughout the entire palliative care course, and data suggest that this is especially valued at the end of a patient’s life.10

Easing Child Distress

Drawing inward

The endpoint of the terminal phase is often marked by a turning inward, away from the external world, by the child. Cognitive and emotional horizons narrow, as all energy is needed simply for physical survival. A generalized irritability is not uncommon. The child may talk very little, and may even retreat from physical contact. Although such withdrawal is not universal, a certain degree of quietness is almost always evident. The child is pulling into himself or herself, not away from others. It is critical to explain this behavior as a normal and expectable precursor to death to the parents so that they do not interpret it as rejection.11,12

Drowsiness and altered consciousness

Diminished wakefulness is also very common during the last days of life13 and is often desirable for the child and family. However, it is also not uncommon for parents and loved ones to want to hold onto every wakeful moment possible. At times this desire can hinder titration of pain-relieving medications because of the worry of further limiting wakefulness. The team should continue efforts to try for a careful balance of comfort and an ability to interact, while at the same time encourage the family to continue their own interactions, such as gentle hugging or touching, talking or singing, with the hope that the child perceives such gestures. One family reread aloud the first book of the Harry Potter series to their dying child, hoping that the story would bring as much joy to him as it had previously.

Escalating pain, dyspnea, and agitation

Three highly common symptoms that may require intensive treatment efforts are escalating pain, dyspnea, and agitation during the final days of life. Full details for management of these distressing symptoms can be found in Chapters 2831, and 32. One challenge to successful management is variability among providers in the approach to medication titration. Children’s Hospital Boston examined adequate symptom management in children with cancer at the end of life and found the following barriers to care:14

In response to these findings, an interdisciplinary taskforce developed guidelines and a standardized order set to achieve greater consistency in medication titration and symptom management outcomes (Box 36-3). When a patient experiences a refractory symptom that cannot be captured through appropriate titration of symptom-relieving medications as described, then sedation to unconsciousness, or palliative sedation, may be indicated. Full details related to consideration, discussion and administration of palliative sedation can be found in Chapter 23.

BOX 36-3 Guidelines for Management of Escalating Pain, Dyspnea, or Agitation at the End of Life

Adapted from Children’s Hospital Boston Guidelines for Management of Escalating Pain/Dyspnea/Agitation at the End of Life. Boston, Mass. Revised 9/2000. All rights reserved.

Noisy breathing

Breathing can become particularly noisy when death is imminent and is often described as the death rattle. This is more common in patients with primary lung disease or brain tumors.15 It is critically important to prepare family members for this possibility. Because this symptom is often present when the child is already unconscious, the child may not experience this as uncomfortable. However, transdermal scopolamine, l-hyoscyamine drops for smaller patients and glycopyrrolate can be helpful in drying secretions and diminishing this symptom.16–18 Treatment of what the family perceives as suffering should be a priority, even if there are differences of opinion within the care team.

Terminal emergencies

Bowel Obstruction

Similarly there are effective strategies for the medical management of bowel obstruction, as delineated in Chapter 33; however, placement of nasogastric suctioning can provide the most immediate and sustained relief.

Delirium and/or Hallucinations

It is common for the child to become less coherent toward the end of life, however, overt hallucinations and agitation can be extremely distressing for both the child and family. Chapter 28 provides an extensive review of assessment and management of delirium. In truly end-of-life instances, the child may respond well to intermittent doses of haloperdol, which can be administered intravenously.

Ensuring comfort during special circumstances

When Fluids and Nutrition are Discontinued

Typically, as a child approaches end of life, there is little drive for drinking and eating, and older patients have indicated that this is not experienced as hunger or thirst.19 It is not uncommon, however, for children to be receiving medically administered fluid and/or nutrition near the end of life, and this may prolong dying without providing benefit in terms of comfort. Continued fluids and nutrition may even contribute to discomfort. For example, in a child dying from an advanced brain tumor, continued fluids can increase cerebral edema and headache. In a child with end-stage lung disease, continued fluid can increase secretions, and at times pulmonary edema, both of which can exacerbate dyspnea. In such circumstances, clinicians and parents may opt to discontinue medically administered fluid and nutrition. However, once discontinued and depending on how long a child is likely to survive, the child’s appearance may change over time. Anticipatory guidance is critical to helping the family through this end-of-life period. The following key considerations should be discussed:

When the Ventilator Is Discontinued

One of the most common ways a child typically dies in the intensive care unit (ICU) is through the discontinuation of ventilator support.20–22 Though difficult to know with certainty, this decision is typically made when there is consensus that the underlying cause of ventilator dependence is irreversible, and continued ventilatory support will not result in a meaningful quality of life. The following considerations are important when the patient, when involved, the family, and the healthcare team reach consensus that ventilator support will be discontinued.

The counseling of families23 is a critical aspect of care for the patient who is to be removed from a ventilator. Before withdrawal, the following issues should be discussed:

Options for Ventilator Withdrawal

Two methods have been described for ventilator withdrawal:24 immediate extubation and terminal weaning. The clinician’s and patient’s comfort, and the family’s perceptions, should influence the choice. In immediate extubation, the endotracheal tube is removed after appropriate suctioning. Humidified air or oxygen is given to prevent the airway from drying. This is the preferred approach to relieve discomfort if the patient is conscious, the volume of secretions is low, and the airway is unlikely to be compromised after extubation. A patient likely to experience significant hemoptysis, for example, may benefit from a terminal wean with the gradual reduction in oxygen and/or ventilator rate at a pace not faster than pharmacologic sedation is administered to treat objective signs of distress from the effects of hypoventilation and hypoxia. In terminal weaning, the ventilator rate, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), and oxygen levels are decreased while the endotracheal tube is left in place. Terminal weaning may be carried out over a period of as little as 30 minutes, or it can be longer. If the patient survives and it is decided to leave the endotracheal tube in place, a Briggs T-piece can be placed.

The following are suggested steps to ensure smooth withdrawal of ventilator support:

Symptom Control

The most common symptoms related to ventilator withdrawal are breathlessness and anxiety. Opioids and benzodiazepines are the primary medications used to provide comfort, typically requiring doses that cause sedation to achieve good symptom control. The dose needed to control symptoms will depend on the neurological status of the patient and the amount of similar medication used up to the time of extubation. In unconscious patients, it should not be assumed that they will not experience distress, and symptom-relieving medications should be administered in advance of planned extubation. Patients who are awake at the time extubation or in whom significant amounts of opioids and benzodiazepines have been used previously will require greater dosages or a change to a barbiturate to achieve symptom control.25 Medication titration should proceed according to guidelines discussed in Chapter 23.

Extensive discussions were held with the ICU staff about the following concerns:

Easing Family Distress

During a resuscitative effort

Approximately 75% of children who experience pulseless cardiac arrest in the hospital, and 90% of those who experience an out-of-hospital arrest will die.26,27 Most hospitals are instituting efforts to pre-empt unexpected cardiorespiratory arrest by instituting protocols to promote early transfer to the ICU.28 Despite these efforts, codes continue to occur and efforts should be made to attend to the family’s distress. Such efforts include identifying a point person for the family, who can serve as a constant presence during the resuscitative effort, provide regular updates, answer questions and make every effort to meet the family’s needs. Families are now regularly invited to be present during resuscitative efforts. The data suggest that when they are present, there is less anxiety, litigation, and second-guessing regarding the efforts and competence of the staff providing that care.29

The lingering child

Hastening death

Rarely, a parent will overtly request that the child’s death be intentionally hastened,30 and this is most commonly associated with parental fears about child suffering. Euthanasia is legal only in the Netherlands22,31,32 and is for children either younger than 1 year old or older than 12 and who are considered able to provide assent. Euthanasia for minors is also under consideration in Belgium.33 There are no legal hastening options for minors in North America. Yet, if the parent requests hastening, it is important to respond with more than just a statement that hastening is not legally permissible. Just as other requests should be explored to identify underlying meaning and fears, so should this type of request. Explanation of legal and effective alternatives, such as further titration of symptom-relieving medications and palliative sedation, is helpful.

Participating in prayer with families

Clinicians are, at times, asked to pray for a child or to lead a family in prayer. This may be an indication of unmet spiritual needs and further exploration of whether it would be helpful to involve the chaplain, if he or she is not already involved, may be warranted. Regardless, the clinician may feel conflicted about whether to participate in or lead a prayer on behalf of the patient because of considerations of professional-personal boundaries and his or her own religious beliefs or spirituality. Consideration of the following options, which attempt to respect the integrity of the clinician’s beliefs and to be supportive of the family’s needs, may be helpful.34,35

At the Time of Death

The pronouncement36

Consider the following steps to pronounce the death:

Death certificate completion

There is tremendous variability in diagnoses used for completion of the death certificate; however, experience suggests that what is written can hold great importance for family members. Guidelines are readily available. In the United States, the National Association of Medical Examiners provides the following guidelines:37

After Death Care

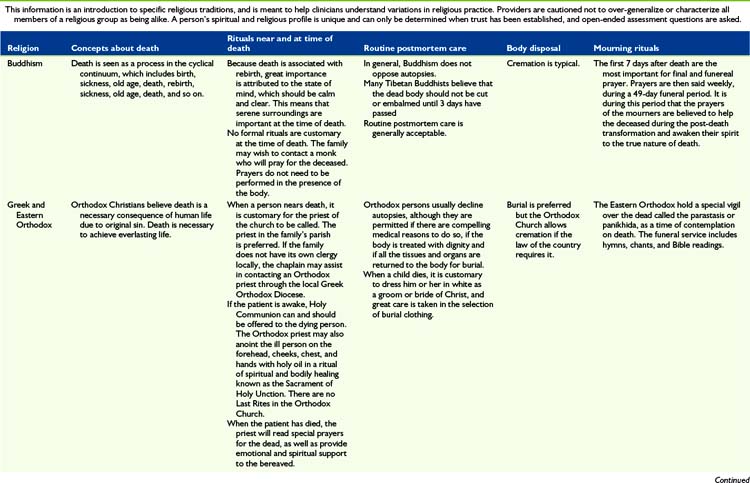

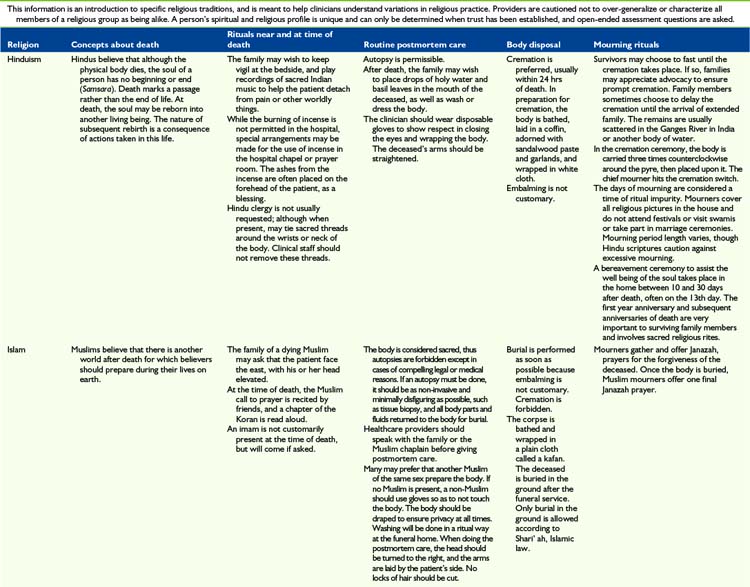

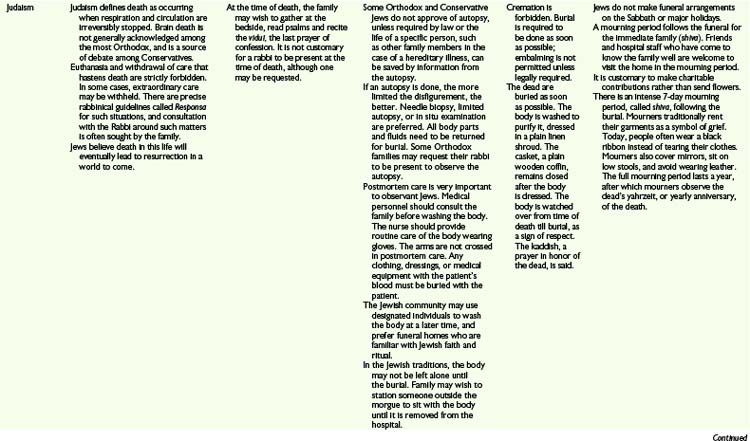

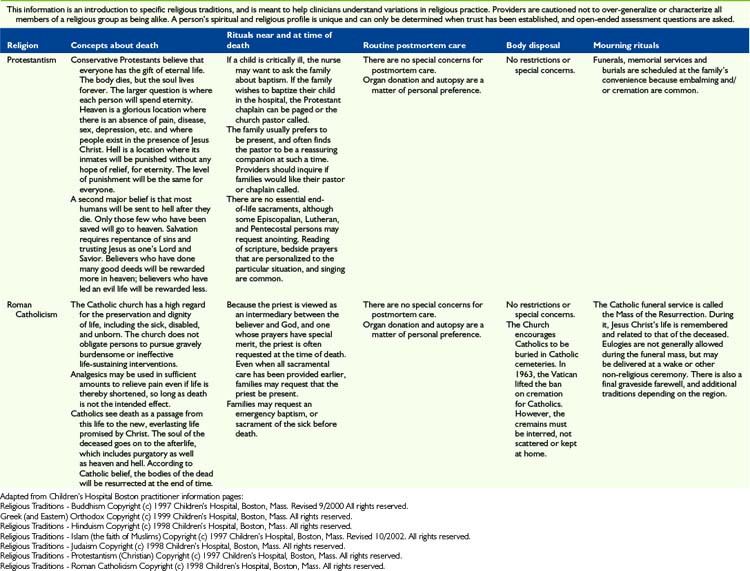

The most important message to relay to parents is that nothing needs to be done in a hurry when their child dies. This is very much a private time for family to say their individual goodbyes. Saying goodbyes and performing rituals are important because they enable parents, siblings, and other family members to express their love, sorrow, relief, regrets, and share precious memories. Many will be guided by religious practices, which can vary considerably (Table 36-2). Washing the child for the last time, dressing the child in special clothes, taking photos, playing favorite music, praying together, touching and cuddling the child, talking to the child, taking foot and handprints, cutting a lock of hair and writing a message or poem for the child are all examples of rituals that families have found helpful and necessary.

Livor mortis

One of the early changes that can be observed is livor mortis, also referred to as lividity, postmortem hypostasis, vibices, and suggilations.38 This is a physical process. While the individual is alive, the heart circulates the blood. When death occurs, circulation stops and the blood begins to settle, by gravity, to the lowest portions of the body. This results in a discoloration of those lower, dependent parts of the body. Although beginning immediately, the first signs of livor mortis are typically seen about 1 hour following death, with full development being observed 2 to 4 hours following death.38

Rigor mortis

Rigor mortis is a chemical change resulting in a stiffening of the body’s muscles following death, resulting from changes in the myofribrils of the muscle tissues. Immediately following death, the body becomes limp and is easily flexed.38 As ATP is converted to ADP and lactic acid is produced lowering the cellular pH, locking chemical bridges are formed between actin and myosin resulting in formation of rigor. Typically, the onset of rigor is first observed 2 to 6 hours following death and develops over the first 12 hours. The onset begins with the muscles of the face and then spreads to all of the muscles during the next 4 to 6 hours. Rigor typically lasts from 24 to 84 hours, after which the muscles begin once again to relax.

Death in the hospital

Once the family has left the hospital, nurses typically prepare to do postmortem care by two staff members who can support one another. Preparation of the body will vary depending on hospital policy, religious and cultural preference, and whether or not the body will be examined by the medical examiner and/or an autopsy will be performed (see Table 36-2). When the body is formally examined, all indwelling lines and tubes must remain intact. Appropriate pads should be placed over puncture or wound sites and under the perineum to contain body fluids if necessary. The body should be dressed in a hospital gown or clothing designated by family.

Non-Medical Examiner Cases

In most hospitals, the body is transported to the morgue in anticipation of being picked up by the funeral home. Body bags and special stretchers are used so that others will not recognize that a body is being transported. At times families object to the child’s body being transported to the morgue and every effort should be made to accommodate such requests. In addition, certain religious observances require different handling of the body (see Table 36-2).

Debriefing staff

Because of role modeling by senior staff, these rounds are generally well attended.

Staff commemoration

With the death of a child, whether that child has been cared for by staff for a short or long time, there are various ways in which to commemorate the child. At the same time, these actions often provide opportunities for self-care. In a study of more than 200 pediatric critical care specialists, 79% contacted families following the death at least sometimes, 72% attended funerals, and only 2.5% thought that it was inappropriate for clinicians to attend funerals. A total of 76% agreed that follow-up contact helps the family, whereas 47% agreed that follow-up contact helps the physicians.39 For a more detailed description of staff commemorative activities see Chapter 18.

The condolence letter or card is one of the simplest gestures that can be made by a clinician and is typically highly valued by family members. Personal experience suggests that these notes are kept indefinitely and become a part of the child’s legacy. A good condolence letter has two goals: to offer tribute to the deceased and to be a source of comfort to the survivors. One of the greatest hurdles to writing these letters is simply finding the right words. Bedell and colleagues offer some concrete suggestions:40 One can begin the letter with a direct expression of sorrow about the death, such as “I am writing to send you my condolences on the death of your son.” Typical themes to include in the letter are:

Clinician acts of kindness and commemoration following a child’s death should not be taken lightly. In a qualitative study41 of bereaved parents whose child was in the care of the ICU three critical themes were identified:41

It is increasingly common for palliative care programs to offer longer-term bereavement support to families and these efforts are described in detail in Chapter 5.

Summary

Mary was a 16-year-old girl with an advanced brain tumor and spinal metastases. Together with her family, her goals were to continue to strive for cancer control, but at the same time enjoy as much time at home in her community, which was several hours away from the hospital. She was passionate about attending school, being with family and friends, and painting (Fig. 36-1). Comprehensive support was put into place at home and Mary’s many symptoms were managed proactively. Her medication regimen was extensive including the following:

| Oral Medication | Indication |

|---|---|

| Dexamethasone 2 mg qid | Cerebral edema |

| Omeprazole 20 mg bid | Gastric prophylaxis |

| Bisacodyl 2 tabs bid | Constipation |

| Ondansetron 8 mg tid | Nausea |

| Metoclopramide 10 mg tid | Nausea |

| Methadone 15 mg tid | Pain |

| Methylphenidate 15 mg qam, 15 mg qnoon | Daytime drowiness |

| Celecoxib 100 mg bid | Antiangiogenic agent |

| Nortryptiline 20 mg qhs | Neuropathic pain |

| Gabapentin 300 mg tid | Neuropathic pain |

| Baclofen 15 mg tid | Muscle spasm |

| Sertraline 100 mg qhs | Depression, anxiety |

| Trazadone 25 mg qhs | Depression, insomnia |

| Intravenous Medication | Indication |

|---|---|

| Dexamethasone 4 mg qid | Cerebral edema |

| Ondansetron 8 mg tid | Nausea |

| Methadone 10 mg qid | Pain |

| Fentanyl 225 mcg/h PCA with 180 mcg bolus q6min | Pain |

| Ativan 1.75 mg IV q4h, 1 mg IV q1h prn | Anxiety |

| Haldol 1 mg IV q6h | Anxiety, agitation, hallucinations |

| Scopolamine patch | Excess secretions |

1 Steinhauser K.E., Christakis N.A., Clipp E.C., McNeilly M., McIntyre L., Tulsky J.A. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476-2482.

2 Bluebond-Langner M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., Belasco C. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2414-2419.

3 Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469-2475.

4 Davies B., Gudmundsdottir M., Worden B., Orloff S., Sumner L., Brenner P. “Living in the dragon’s shadow”: fathers’ experiences of a child’s life-limiting illness. Death Stud. 2004;28(2):111-135.

5 Bicanovsky L. Comfort Care: Symptom control in the dying. In: Walsh D., Caraceni A.T., Fainsinger R., et al, editors. Palliative medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009.

6 Wijdicks E.F. The diagnosis of brain death. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(16):1215-1221.

7 Bulow H.H., Sprung C.L., Reinhart K., et al. The world’s major religions’ points of view on end-of-life decisions in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(3):423-430.

8 Kreicbergs U.C., Lannen P., Onelov E., Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3307-3312.

9 Meert K.L., Eggly S., Pollack M., et al. Parents’ perspectives regarding a physician-parent conference after their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2007;151(1):50-55. 55 e51–55 e52

10 Cherin D.A., Enguidanos S.M., Jamison P. Physicians as medical center “extenders” in end-of-life care: physician home visits as the lynch pin in creating an end-of-life care system. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2004;23(2):41-53.

11 Sourkes B.M. The deepening shade: psychological aspects of life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982.

12 Sourkes B.M. Armfuls of time : the psychological experience of the child with a life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

13 Drake R., Frost J., Collins J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(1):594-603.

14 Houlahan K.E., Branowicki P.A., Mack J.W., Dinning C., McCabe M. Can end of life care for the pediatric patient suffering with escalating and intractable symptoms be improved? J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23:45-51.

15 Morita T., Tsunoda J., Inoue S., Chihara S. Risk factors for death rattle in terminally ill cancer patients: a prospective exploratory study. Palliat Med. 2000;14(1):19-23.

16 Wildiers H., Menten J. Death rattle: prevalence, prevention and treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(4):310-317.

17 Bennett M., Lucas V., Brennan M., Hughes A., O’Donnell V., Wee B. Using anti-muscarinic drugs in the management of death rattle: evidence-based guidelines for palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16(5):369-374.

18 Back I.N., Jenkins K., Blower A., Beckhelling J. A study comparing hyoscine hydrobromide and glycopyrrolate in the treatment of death rattle. Palliat Med. 2001;15(4):329-336.

19 Dalal S., Del Fabbro E., Bruera E. Is there a role for hydration at the end of life? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3(1):72-78.

20 Finan E., Bolger T., Gormally S.M. Modes of death in neonatal intensive care units. Ir Med J. 2006;99(4):106-108.

21 Sands R., Manning J.C., Vyas H., Rashid A. Characteristics of deaths in paediatric intensive care: a 10-year study. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14(5):235-240.

22 Verhagen A.A., Dorscheidt J.H., Engels B., Hubben J.H., Sauer P.J. End-of-life decisions in Dutch neonatal intensive care units. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(10):895-901.

23 von Gunten C., Weissman D.E. Fast Fact and Concept #033: Ventilator Withdrawal Protocol (Part I). 2010. www.aahpm.org/cgi-bin/wkcgi/view?status=A%20&search=182&id=174&offset=0&limit=25. Accessed March 20

24 Campbell M.L. How to withdraw mechanical ventilation: a systematic review of the literature. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007;18(4):397-403. quiz 344–395

25 Truog R.D., Berde C.B., Mitchell C., Grier H.E. Barbiturates in the care of the terminally ill. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(23):1678-1682.

26 Nadkarni V.M., Larkin G.L., Peberdy M.A., et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295(1):50-57.

27 Topjian A.A., Nadkarni V.M., Berg R.A. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in children. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(3):203-208.

28 Parshuram C.S., Hutchison J., Middaugh K. Development and initial validation of the Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System score. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R135.

29 Nibert L., Ondrejka D. Family presence during pediatric resuscitation: an integrative review for evidence-based practice. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(2):145-147.

30. Dussel V., Joffe S., Hilden J.M., Watterson-Schaeffer J., Weeks J.C., Wolfe J. Considerations about hastening death among parents of children who die of cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):231-237.

31 Verhagen A.A., Sauer P.J. End-of-life decisions in newborns: an approach from the Netherlands. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):736-739.

32 Vrakking A.M., van der Heide A., Arts W.F., et al. Medical end-of-life decisions for children in the Netherlands. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(9):802-809.

33 Pousset G., Bilsen J., De Wilde J., et al. Attitudes of adolescent cancer survivors toward end-of-life decisions for minors. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1142-e1148.

34 Cadge W., Ecklund E.H. Prayers in the clinic: how pediatric physicians respond. South Med J. 2009;102(12):1218-1221.

35 Fast Fact and Concept #120: Physicians and prayer requests. www.aahpm.org/cgi-bin/wkcgi/view?status=A%20&search=151&id=554&offset=0&limit=25. Accessed March 22, 2010

36 Fast Fact and Concept #004; Death Pronouncement in the Hospital.. www.aahpm.org/cgi-bin/wkcgi/view?status=A%20&search=126&id=95&offset=0&limit=25. Accessed March 22, 2010

37 National Association of Medical Examiners. http://thename.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=113&Itemid=58. Accessed March 17, 2010

38 Lee Goff M. Early post-mortem changes and stages of decomposition in exposed cadavers. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;49(1–2):21-36.

39 Borasino S., Morrison W., Silberman J., Nelson R.M., Feudtner C. Physicians’ contact with families after the death of pediatric patients: a survey of pediatric critical care practitioners’ beliefs and self-reported practices. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1174-e1178.

40 Bedell S.E., Cadenhead K., Graboys T.B. The doctor’s letter of condolence. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(15):1162-1164.

41 Macdonald M.E., Liben S., Carnevale F.A., et al. Parental perspectives on hospital staff members’ acts of kindness and commemoration after a child’s death. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):884-890.