Early pregnancy care

Miscarriage

The aetiology of miscarriage

Abnormalities of the uterus

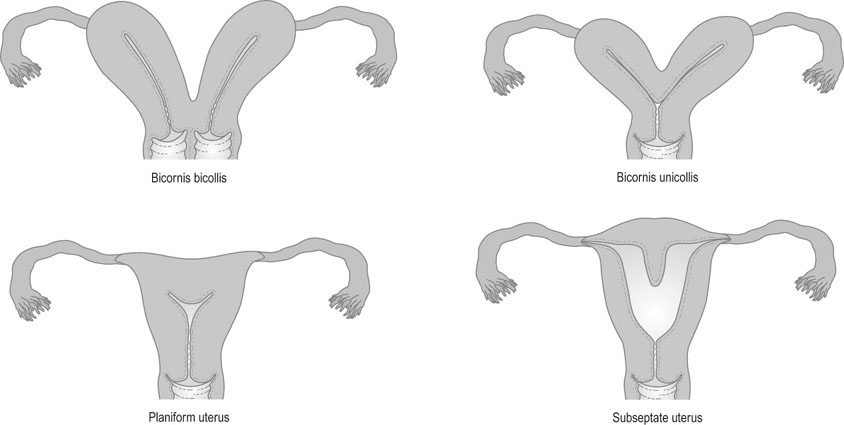

Congenital abnormalities of the uterine cavity, such as a bicornuate uterus or subseptate uterus, may result in miscarriage (Fig. 18.1). Uterine anomalies can be demonstrated in 15–30% of women experiencing recurrent miscarriages. The impact of the abnormality depends on the nature of the anomaly. The fetal survival rate is 86% where the uterus is septate and worst where the uterus is unicornuate. It must also be remembered that over 20% of all women with congenital uterine anomalies also have renal tract anomalies. Following damage to the endometrium and inner uterine walls, the surfaces may become adherent, thus partly obliterating the uterine cavity (Asherman’s syndrome). The presence of these synechiae may lead to recurrent miscarriage.

Clinical types of miscarriage

Threatened miscarriage

The first sign of an impending miscarriage is the development of vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy (Fig. 18.2). The uterus is found to be enlarged and the cervical os is closed. Lower abdominal pain is either minimal or absent. Most women presenting with a threatened miscarriage will continue with the pregnancy irrespective of the method of management.

Inevitable/incomplete miscarriage

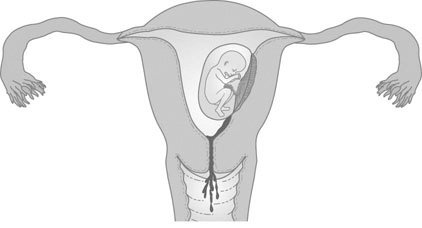

The patient develops abdominal pain usually associated with increasing vaginal bleeding. The cervix opens, and eventually products of conception are passed into the vagina. However, if some of the products of conception are retained, then the miscarriage remains incomplete (Fig. 18.3).

Missed miscarriage (empty gestation sac, embryonic loss, early and late fetal loss)

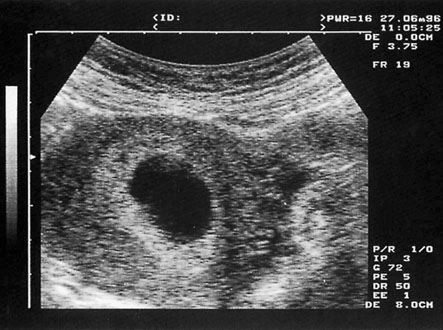

In empty gestation sac (anembryonic pregnancy or blighted ovum) a gestational sac of ≥25 mm is seen on ultrasound (Fig. 18.4), but there is no evidence of an embryonic pole or yolk sac or change in size of the sac on rescan 7 days later. Embryonic loss is diagnosed where there is an embryo ≥7 mm in size without cardiac activity or where there is no change in the size of the embryo after 7 days on scan. Early fetal demise occurs when a pregnancy is identified within the uterus on ultrasound consistent with 8–12 weeks size, but no fetal heartbeat is seen. These may be associated with some bleeding and abdominal pain or be asymptomatic and diagnosed on ultrasound scan. The pattern of clinical loss may indicate the underlying aetiology, for example, antiphospholipid syndrome tends to present with recurrent fetal loss.

Management

Non-sensitized Rhesus (Rh) negative women should receive anti-D immunoglobulin for miscarriages over 12 weeks of gestation (including threatened) and all miscarriages where the uterus is evacuated (whether medically or surgically).

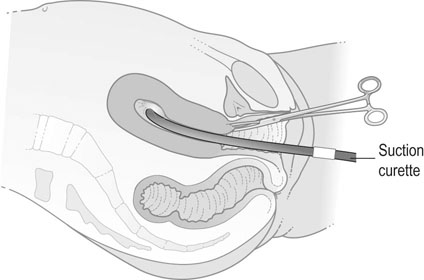

Surgical management

Surgical evacuation of retained products of conception involves dilatation of the cervix and suction curettage to remove the products (Fig. 18.5). This is the modality of choice when there is heavy bleeding or persistent bleeding, if the vital signs are unstable or in the presence of infected retained tissue. Serious complications of surgical treatment occur in 2% of cases and include perforation of the uterus, cervical tears, intra-abdominal trauma, intrauterine adhesions and haemorrhage. Intrauterine infection may result in tubal infection and tubal obstruction with subsequent infertility. Screening for infection including Chlamydia trachomatis should be considered and antibiotic prophylaxis given if clinically indicated. If uterine perforation is suspected and there is evidence of intraperitoneal haemorrhage or damage to the bowel, then a laparoscopy or laparotomy should be performed.

Ectopic pregnancy

The term ‘ectopic pregnancy’ refers to any pregnancy occurring outside the uterine cavity.

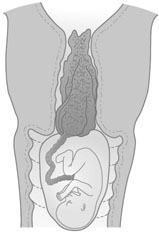

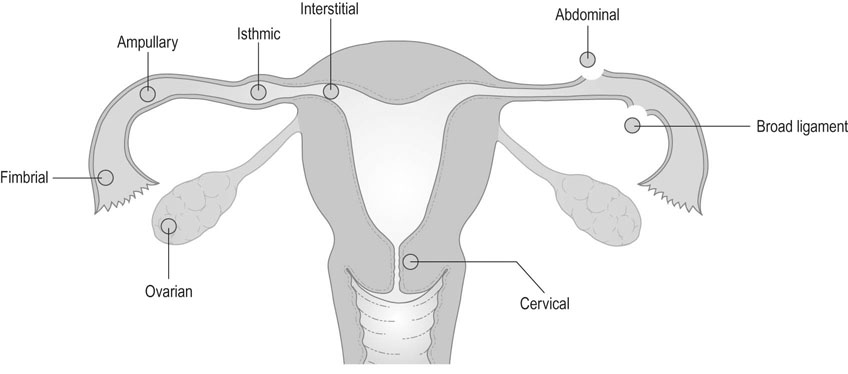

The most common site of extrauterine implantation is the Fallopian tube, but it may occur in the ovary as an ovarian pregnancy, in the abdominal cavity as an abdominal pregnancy, or in the cervical canal as a cervical pregnancy (Fig. 18.6).

Pathology

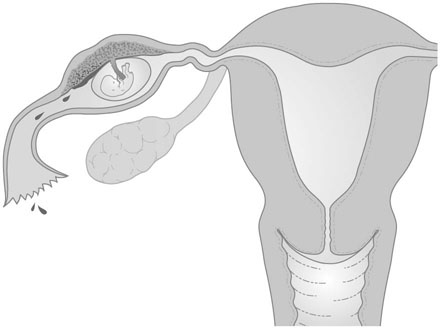

Implantation may occur in a variety of sites, and the outcome of the pregnancy will depend on the site of implantation. Abdominal pregnancy may result from direct implantation of the conceptus in the abdominal cavity or on the ovary, in which case it is known as primary abdominal pregnancy, or it may result from extrusion of a tubal pregnancy with secondary implantation in the peritoneal cavity, which is known as secondary abdominal pregnancy. Implantation of the conceptus in the tube results in hormonal changes that mimic normal pregnancy. The uterus enlarges and the endometrium undergoes decidual change. Implantation within the fimbrial end or ampulla of the tube allows greater expansion before rupture occurs, whereas implantation in the interstitial portion or the isthmic part of the tube presents with early signs of haemorrhage or pain (Fig. 18.7).

Diagnosis

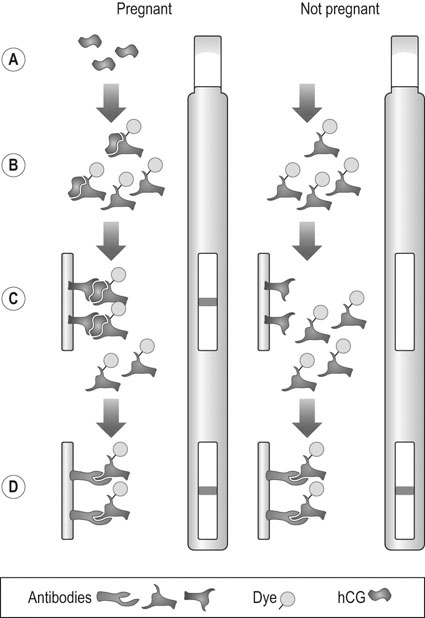

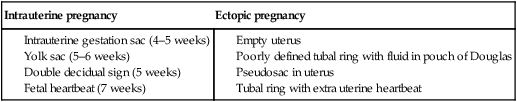

If sufficient blood loss has occurred into the peritoneal cavity, the haemoglobin level will be low and the white cell count will be usually normal or slightly raised. Serum hCG measurement will exclude ectopic pregnancy if negative with a specificity of greater than 99%, and urinary hCG with modern kits that can be used on the ward will detect 97% of pregnancies. In the presence of a viable intrauterine pregnancy, the serum hCG will double over a 48 hour period in 85% of cases (compared with 15% of ectopic pregnancies). A normal intrauterine pregnancy will usually be visualized on scan where the serum hCG level is more than 1000 iu/L (the discriminatory zone). Serial measurements of serum hCG levels in conjunction with ultrasound diagnosis can distinguish early intrauterine pregnancy from miscarriage or ectopic pregnancies in up to 85% of cases. Ultrasound scan of the pelvis may demonstrate tubal pregnancy in 2% of cases (Fig. 18.8) or suggest it by other features such as free fluid in the peritoneal cavity, but is mainly of help in excluding intrauterine pregnancy (Table 18.2). Intrauterine pregnancy can usually be identified by transabdominal scan at 6 weeks gestation and somewhat sooner by transvaginal scan at 5–6 weeks gestation. Occasionally, there may be no clinical signs of an ectopic pregnancy but if curettage samples submitted for histopathology show evidence of decidual reaction and the Arias–Stella phenomenon is present then it is advisable to consider laparoscopy.

Table 18.2

Features of intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy on transvaginal scan

| Intrauterine pregnancy | Ectopic pregnancy |

Management

Surgical management

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the options for treatment are:

• Salpingectomy: If the tube is badly damaged, or the contralateral tube appears healthy, the correct treatment is removal of the affected tube. If implantation has occurred in the interstitial portion of the tube, then it may be necessary to resect part of the uterine horn in addition to removing the tube.

• Salpingotomy: Where the ectopic pregnancy is contained within the tube, it may be possible to conserve the tube by removing the pregnancy and reconstituting the tube. This is particularly important where the contralateral tube has been lost. The disadvantage is the persistence of trophoblastic tissue requiring further surgery or medical treatment in up to 6% of cases.

Subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rates are similar after both types of treatment, although the risk of recurrent ectopic pregnancy is greater after salpingotomy. Both can be carried out as an open procedure or laparoscopically. The laparoscopic approach is associated with quicker recovery time, shorter stay in hospital and less adhesion formation, and is the method of choice if the patient is stable.

Trophoblastic disease

Abnormality of early trophoblast may arise as a developmental anomaly of placental tissue, and results in the formation of a mass of oedematous and avascular villi. There is usually no fetus but the condition can be found in the presence of a fetus. The placenta is replaced by a mass of grapelike vesicles known as a hydatidiform mole (Fig. 18.10).

Management

Pregnancy is contraindicated until 6 months after the serum hCG levels fall to normal. Oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives and HRT can be used as soon as hCG levels are normal. The risk recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is 1 in 74 and serum hCG levels should be checked 6 weeks after any subsequent pregnancy.

Vomiting in early pregnancy

Management

• Taking small, carbohydrate meals and avoiding fatty foods.

• Powdered ginger root or pyridoxine (vitamin B6).

• Avoiding large volume drinks, especially milk and carbonated drinks.

A history of persistent, severe vomiting with evidence of dehydration requires admission to hospital for assessment and management of symptoms.

Thromboprophylaxis with compression stockings and low-molecular weight heparin should be considered. Most women will settle in 24–48 hours with these supportive measures. Once the vomiting has ceased, small amounts of fluid and eventually food can be re-introduced.