26 Ear, nose and throat surgery

Ear

Anatomy

External ear

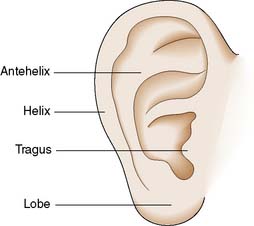

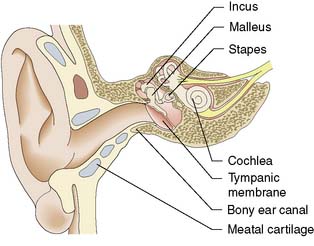

The pinna (Fig. 26.1) is made of fibroelastic cartilage. The external auditory meatus has an outer cartilage portion; the inner part is formed by the tympanic bone (Fig. 26.2). It is lined by squamous epithelium and contains ceruminous glands that produce wax. There is very little subcutaneous tissue and soft tissue swelling is very painful.

Middle ear

The vibrating tympanic membrane is conical and attached to the margin of the bony ear canal laterally and to the handle of the malleus, the first of the three ossicles, medially (Fig. 26.2). The head of the malleus is attached to the body of the incus in the space superior to the middle ear known as the attic. The long process of the incus attaches to the head of the stapes via its lenticular process. The stapes is joined to the oval window margin by the annular ligament. The middle ear is lined by simple cuboidal epithelium containing some mucus-secreting cells. The middle ear space is connected to the nasopharynx by the Eustachian tube, which maintains the middle ear at atmospheric pressure.

Physiology

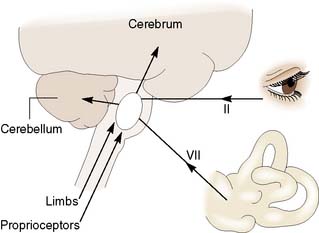

The pinna funnels sound into the ear canal. The tympanic membrane lever mechanism, the ossicular lever mechanism and the large size of the drum relative to the stapes footplate act as an impedance-matching transformer. Vibrations in air are thus transferred to the cochlear fluids without excessive loss of energy. The cochlea converts these endolymph vibrations into electrical impulses in the auditory nerve, by stimulation of hair cells in the organ of Corti. The maximum response to high frequencies occurs in the basal turn of the cochlea. Low frequencies maximally stimulate the apex. Auditory neurons connect via the brainstem to the auditory cortex, where again different groups of cells are stimulated by nerve impulses coded for different frequencies. The hair cells in the ampullae of the semicircular canals are stimulated by angular acceleration. The saccule and utricle are stimulated by linear acceleration. Information from the labyrinths, eyes and limbs is combined within the brainstem. Connections from the vestibular nuclei pass to the cortex and the cerebellum (Fig. 26.3).

Assessment

Clinical features

Disorders of the external or middle ear can impair sound transmission to the inner ear and cause conductive deafness. Sensorineural deafness results from lesions of the cochlea or its nerve. Deafness is often associated with a noise in the ear (tinnitus). Ear pain (otalgia) may be due to ear disease but may also be referred from other sites (Table 26.1). Ear-related disorders of balance usually cause a sensation of movement (vertigo), most often rotation. ‘Unsteadiness’ however, typically has a non-otological cause. Patients with ear disease occasionally fall to the ground but never lose consciousness.

| Pharynx and larynx |

Audiometry

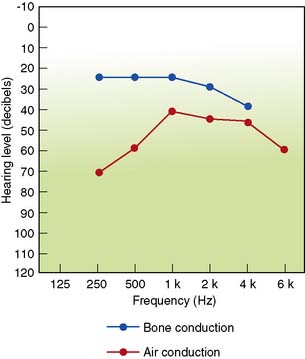

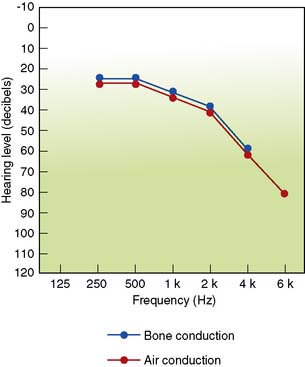

Hearing by air conduction can be assessed by pure tone audiometry, in which sounds of known pitch and loudness are presented to each ear in turn via headphones. Bone conduction (cochlear function) can be separately tested by applying sounds to the mastoid process. A masking tone is needed if the two cochleae are to be tested separately. The difference between the air and bone conduction gives the level of conductive hearing loss (Figures 26.4 and 26.5). The patient’s ability to hear speech can be tested by presenting lists of words via headphones. The percentage correctly identified at different loudness levels allows derivation of a speech reception threshold (50% of words correct) and a discrimination score. Middle ear function (compliance) can be assessed by tympanometry. The amount of sound from a probe reflected back from the drum is measured while the pressure in the ear canal is made to vary. The compliance is maximal when the pressure in the ear canal equals the pressure in the middle ear, because when pressure is the same on both sides of the drum it is maximally mobile. Tympanometry is most often used to confirm the presence of fluid in the middle ear.

Temporal bone imaging

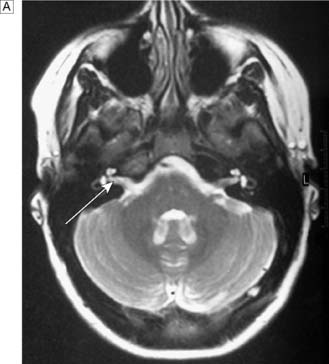

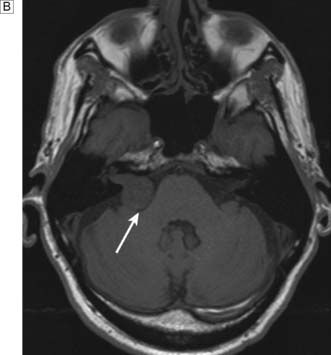

In patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, MRI is used to detect an acoustic neuroma (Fig. 26.6). MRI also demonstrates the presence of normal fluid in the cochlea before attempting cochlear implantation. CT scans can be used to demonstrate temporal bone anatomy, congenital abnormalities and fractures or unusual pathology.

Diseases of the pinna

Bat ears

A developmental abnormality results in absence of the antihelical fold (see Fig. 26.1). This produces prominent ears that cause embarrassment. The abnormality can be corrected surgically.

Diseases of the middle ear

Acute suppurative otitis media

This is a bacterial infection of the middle ear space, usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae, most commonly occurring in young children (3 years of age and under). Children present with a combination of ear pain (otalgia), fever and malaise. On examination, dilated blood vessels are seen on the drum surface in the early stages. The drum then becomes red and begins to bulge. Perforation with discharge frequently occurs, usually followed by spontaneous healing. Antibiotic therapy remains controversial: the majority of cases resolve spontaneously in a few days (EBM 26.1). Antibiotics are useful in high risk patients (e.g. immunosuppression) as they shorten the episodes and reduce the rate of infective complications such as mastoiditis, facial palsy or meningitis.

Otitis media with effusion (OME), or ‘glue ear’

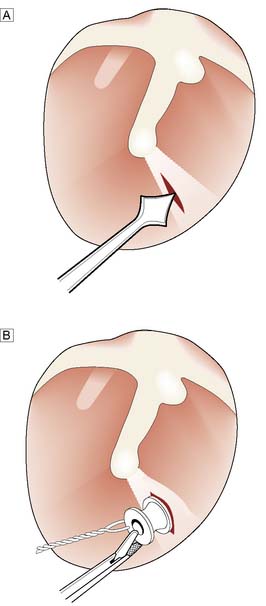

In this condition, fluid accumulates in the middle ear space, usually in children. A minority of adult cases are caused by nasopharyngeal tumours and systemic disease. Childhood OME causes hearing loss and may interfere with the acquisition of language and performance at school. Virtually all cases resolve spontaneously, but this may take as long as 10 years. Initial management involves documentation of the presence of effusion and the degree of hearing loss during a period of watchful waiting. If the effusions persist, hearing may be improved by drainage of the effusion (myringotomy) and insertion of a ventilation tube (Fig. 26.8). In children, removal of the adenoids leads to more effective resolution. Spontaneous resolution may also occur in adults, but often effusions persist. Ventilation tubes can also be of value, but some cases are better managed with a hearing aid.

Chronic suppurative otitis media

This causes aural discharge and deafness.

Atticoantral or squamous disease

Summary Box 26.1 Otitis media

• Acute otitis media is extremely common under the age of 3 years

• The child typically awakes crying at night with a painful ear. The diagnosis is confirmed by a red, inflamed bulging tympanic membrane on otoscopy

• Pain relief is important. Antibiotics should be given to prevent the development of complications

• Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) occurs transiently in many children and is manifested by temporary hearing impairment. Most cases settle spontaneously. Bilateral persistent hearing impairment may demand surgery (adenoidectomy, or insertion of a grommet)

• Chronic otitis media involves the middle ear and mastoid mucosa. There is permanent perforation of the tympanic membrane, hearing loss and a mucopurulent discharge. Inactive ears require closure of the perforated membrane (myringoplasty) and rebuilding of the ossicular chain. Ears with cholesteatoma may require surgical removal of the posterior canal wall to open the attic or mastoid cavity and so reduce the risk of meningitis, intracranial abscess and facial palsy.

Diseases of the inner ear

Deafness

Deafness is most commonly due to changes in the cochlea. Ageing produces a gradual deterioration in hearing acuity (presbycusis). The cochlea may be damaged by chronic noise exposure, blast injuries and temporal bone fractures. Significant noise exposure may occur in heavy industry and agriculture, from playing in rock bands and shooting. Deafness may also be inherited or a manifestation of systemic disease. Some drugs, such as aminoglycosides and cytotoxic agents like cisplatinum, can damage the cochlea. Viral infections such as mumps and rubella can also cause sensorineural deafness. Unilateral hearing loss occurs in acoustic neuroma (Fig. 26.6B).

Nose

Anatomy

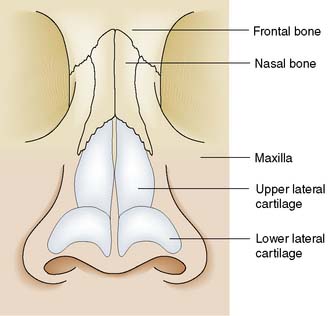

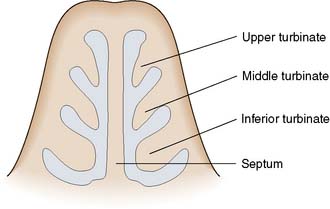

The nasal skeleton consists of two nasal bones superiorly and two pairs of cartilages inferiorly (Fig. 26.9). The nasal cavity is divided in two by a partition composed of cartilage anteriorly and bone posteriorly (the nasal septum). Three turbinate bones protrude from the lateral wall of the nose (Fig. 26.10). Between the inferior and middle turbinates is the middle meatus of the nose. Most of the paranasal sinuses open into this area under cover of a soft tissue flap known as the uncinate process. Obstruction of the sinus ostia in this area can cause sinus pain and may lead to sinus infection. Superior to the superior turbinate is an area of olfactory epithelium from which arise the nerve fibres of the olfactory nerve. The anterior portion of the nasal septum is called Little’s area. Here prominent veins are often found, and nose bleeds most often arise from this part of the nose.

Assessment

Imaging

Imaging is not required if nasendoscopy is normal. Images are useful preoperatively to give the surgeon a guide as to individual variations especially in the areas of potential hazard – orbital wall, floor of the anterior cranial fossa (skull base) and to minimize the risk of complications. Computed tomography (CT) is the best means of imaging the paranasal sinuses and also gives information about the middle meatus of the nose, where the sinus ostia are situated (Fig. 26.11). The sinuses can also be visualized by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but the bony anatomy is not shown and mucosal disease is exaggerated.

Diseases of the nose

Trauma

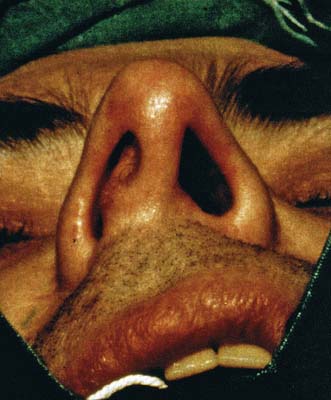

This may result in fracture and displacement of the nasal bones. If the fracture is not reduced within 14 days, it is usually fixed and hard to mobilize. There may also be displacement and fracture of the septal cartilage and bone (deviated nasal septum, Fig. 26.12). Corrective septoplasty surgery requires a post-trauma interval of 3 months to allow for soft tissue repair prior to surgery. Bleeding into the septum causes a septal haematoma, resulting in severe nasal obstruction. This should be drained under aseptic conditions, to prevent a septal abscess and collapse of the bridge.

Nasal polyps

Oedematous paranasal sinus mucosa extrudes through sinus ostia to produce nasal polyps. Most are multiple swellings from the ethmoid sinuses. Rarely, there is a single posterior protrusion from the maxillary sinus (antrochoanal polyp). Unilateral disease is usually defined by a prebiopsy CT (Fig. 26.13). Temporary improvement in the resulting nasal obstruction can be produced by topical or systemic steroids. As most polyps eventually recur following excision, many patients opt for periodic courses of steroid therapy, and only resort to surgery when symptoms get out of hand. Endoscopic clearance is facilitated by use of the micro- debrider (Fig. 26.14).

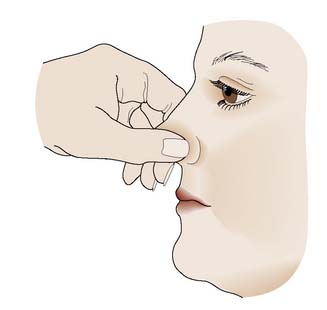

Epistaxis

Nose bleeds may be associated with a number of disease processes (Table 26.2). They are common in healthy children and young adults. Bleeding usually arises from Little’s area and can be controlled by squeezing the nose (Fig. 26.15). In the elderly, more severe bleeding from further back in the nose may occur. In these cases, a nasal pack may be required to arrest the bleeding. Bleeding may be associated with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other antithrombotic therapy in this group. Severe bleeding not controlled by a pack can be arrested by clipping either the sphenopalatine, anterior ethmoid or maxillary artery.

| Bleeding disorders |

Summary Box 26.2 Epistaxis

• Epistaxis in young patients usually arises from a small blood vessel in Little’s area; in older individuals, it arises from an arteriosclerotic vessel located more posteriorly

• Pressure on Little’s area by compressing the anterior septum usually stops the bleeding, and topical 1 in 1000 adrenaline (epinephrine) on cotton wool may be helpful

• Bleeding more posteriorly may require balloon compression or packing

• Coagulation defects should always be excluded. Some of these will be caused by alcohol or non-steroidal analgesics

• In persistent epistaxis, it may be necessary to clip an artery e.g. the sphenopalatine.

Paranasal sinuses

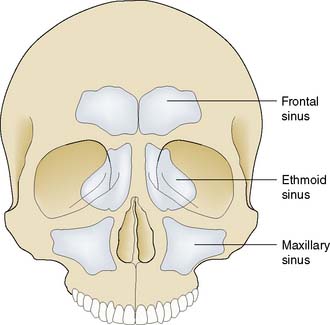

Anatomy

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled cavities that open into the nasal cavity, mostly into the middle meatus of the nose. The maxillary sinuses occupy the cheeks (Fig. 26.16) and have ostia quite high in the sinus wall. The ethmoid labyrinth consists of a number of air cells lying between the orbit and the lateral wall of the nose. The frontal sinus is an ethmoid air cell that has migrated into the frontal bone, and it is connected to the nose via the frontonasal duct, which passes down to the middle meatus. The sphenoid sinus is posterior to the ethmoid labyrinth, inferior to the pituitary fossa.

Diseases of the paranasal sinuses

Sinusitis

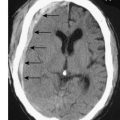

Acute sinusitis is usually managed medically. Chronic sinusitis may result from failure of resolution of acute infection or may arise insidiously. Surgical treatment is frequently required and includes enlargement of the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus, often with clearance of infected ethmoid cells. Frontal and sphenoid sinusitis are much less common. Infection may spread from the sinuses, usually the ethmoid or frontal sinuses, to involve other areas such as the cranial cavity or orbit (Fig. 26.17).

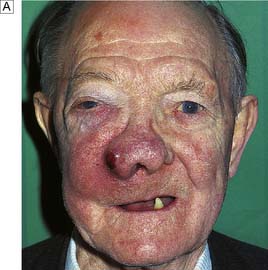

Tumours

The most common malignant neoplasm found in the paranasal sinuses is squamous carcinoma, but adenocarcinomas are seen in workers in the furniture industry, and numerous rare tumour types are also recognized. The most common sites of origin are the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. Unfortunately, the disease has often spread beyond the primary site at presentation (Fig. 26.18). These relatively uncommon tumours are managed by a combination of surgery and radiotherapy, or by local surgery and topical chemotherapy.

Mouth

Diseases of the mouth

Leukoplakia

Leukoplakia (white patch) develops on the oral mucosa as a response to chronic irritation – for example, by a rough tooth, tobacco or alcohol (especially brown spirits) – causing hyperkeratosis (Fig. 26.19). This may progress to dysplasia and cellular atypia, thus leukoplakia is a pre-malignant condition. Removal of both the patches and the causative factors can prevent progression.

Tumours

Squamous carcinoma of the tongue is the most common neoplasm seen in the oral cavity. Lesions cause induration of the tongue, usually with ulceration (Fig. 26.20). Lymphatic spread occurs to the submental nodes and thence to other deep cervical nodes. Smoking and heavy spirit drinking are predisposing factors. Small lesions can be treated by local excision or radioactive implants (iridium wires), but more extensive tumours require excision with a margin of normal tissue. This often includes excision of part of the mandible.

Oropharynx

Diseases of the oropharynx

Tonsillitis

This is due to bacterial infection of the tonsils, usually with Strep. pyogenes. Patients present with episodic sore throat associated with dysphagia, lymph node enlargement, fever and malaise. Tonsillitis must be differentiated from viral sore throats, which are not usually associated with pyrexia and often form part of a more generalized upper respiratory tract infection. Infectious mononucleosis can easily be confused with tonsillitis (EBM 26.2). Tonsillitis may be complicated by the development of a peritonsillar abscess (quinsy). This may require incision and drainage. Recurrent tonsillitis can be treated successfully by tonsillectomy (EBM 26.3).

26.3 Indications for tonsillectomy

• sore throats are due to acute tonsillitis

• the episodes of sore throat are disabling and prevent normal functioning

• seven or more well documented, clinically significant, adequately treated sore throats in the preceding year or

• five or more such episodes in each of the preceding two years or

• three or more such episodes in each of the preceding three years.’

SIGN Guideline 117; 2010 Management of sore throat and indications for tonsillectomy

Snoring and sleep apnoea

Summary Box 26.3 Tonsils and adenoids

• Adenoids are large in small children but become relatively smaller with age

• They may cause nasal obstruction and be involved in the pathogenesis of otitis media with effusion and childhood sleep apnoea

• Tonsils may require removal because of recurrent tonsillitis or peritonsillar abscess in adults and children. Children with sleep apnoea may also benefit from tonsillectomy

• Unilateral tonsillar enlargement may be due to squamous carcinoma or lymphoma.

to sleep poorly, wake unrefreshed and become drowsy during the day. If significant apnoea is confirmed by overnight monitoring, the use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may be indicated. Simple snoring can be improved by weight loss and reduction of nocturnal alcohol intake. Sleep apnoea syndrome can also occur in children, in whom adenotonsillectomy will cure over 80%.

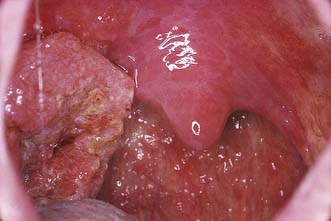

Tumours

B cell lymphomas occur mostly in adults (with a peak in those aged 50–60 years). There is a smooth enlargement of the affected tonsil. Squamous carcinoma usually presents with ulceration of the tonsil (Fig. 26.21). The traditional association with cigarette smoking is less strong, as more now seem related to prior human papilloma virus exposure. Treatment is by (chemo) radiotherapy or surgery (including transoral laser resection).

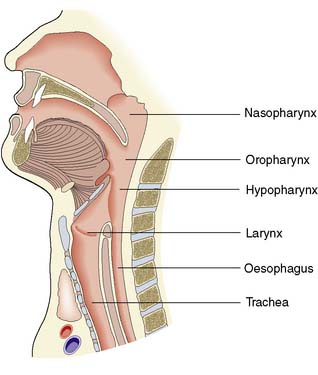

Hypopharynx

Anatomy

Below the oropharynx, the aerodigestive tract divides into an air passage (larynx/trachea) and an alimentary passage (oesophagus). The entrance to the air passage is protected by a purse string mechanism formed when the mobile cartilage of the epiglottis is drawn down over the laryngeal inlet as the aryepiglottic folds shorten. Closure of the false cords forms a second sphincteric layer to protect against aspiration. Glottic closure, conversely, serves chiefly to stop air escaping from the chest, as when sustaining a long note in phonation, straining or lifting (fixing the chest volume). The entry of material into the oesophagus is controlled by the cricopharyngeus ring of muscle. Lateral to the larynx, the pharynx continues inferiorly on both sides into a blind-ended pit known as the pyriform fossa (Fig. 26.22).

Assessment

Clinical features

Obstruction of the oesophagus and disorders that interfere with the muscle activity involved in swallowing cause dysphagia. Physical obstruction causes dysphagia that is worse for solids, whereas neurological disorders cause more difficulty with liquids. Hypopharyngeal pain may be felt locally or retrosternally, or may be referred to the ear (see Table 26.1). The level of obstructive dysphagia is always below the level at which the symptom is experienced. Hence dysphagia localized by the patient in the pharynx requires an assessment down to the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Larynx

Anatomy

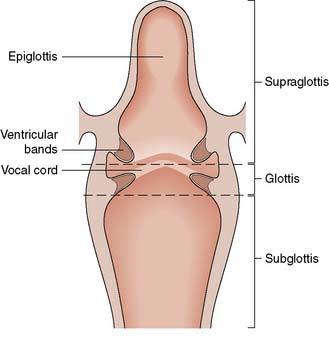

The larynx has a cartilaginous framework. Superiorly, it is supported and protected anteriorly by the thyroid cartilage. Inferiorly lies the cricoid cartilage, which connects to the trachea (Fig. 26.23). Within the laryngeal lumen, two soft tissue folds pass from anterior to posterior. The upper folds are the ventricular bands or ‘false cords’. The lower pair are the (true) vocal cords, which are responsible for phonation. These consist of a vocal ligament covered with mucosa. The vibrating free edge of the mucosa is important in achieving glottic closure and voice quality.

Assessment

Clinical features

Hoarseness of the voice is the cardinal symptom of laryngeal dysfunction. Patients may also complain of pain locally or referred to the ear (see Table 26.1). The voice is weak and breathy in unilateral vocal cord palsy, but rough and husky in severe laryngitis and laryngeal cancer. Patients with psychogenic dysphonia often have a squeaky voice quality.

Diseases of the larynx

Tumours

Summary Box 26.4 Carcinoma of the larynx

• Persistent hoarseness in smokers should be assumed to be carcinoma of the larynx until proved otherwise

• Up to 90% of T1 glottic tumours can be cured by radiotherapy or transoral laser resection

• More extensive or recurrent disease may require removal of the larynx

• Following laryngectomy, the trachea is brought out on to the surface of the neck. Speech production is aided by a valve in a fistula between the trachea and the oesophagus.

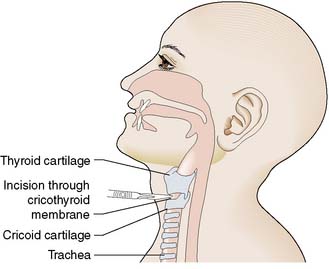

Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy may be required to relieve acute upper airway obstruction (Table 26.3). It is carried out by creating a window in the anterior tracheal wall at the level of the second and third tracheal rings and introducing a suitable tube. When short-term airway support and the causative pathology allow, the situation is better managed by passing an endotracheal tube. Cricothyrotomy (Fig. 26.24) provides a rapid short-term solution to airway obstruction and can be carried out with makeshift equipment. Foreign bodies in the upper airway can be displaced by turning a small child upside down. In a larger individual, a ‘bear hug’ around the chest and abdomen may expel the item (Heimlich’s manoeuvre).

| Children |

Neck

Anatomy

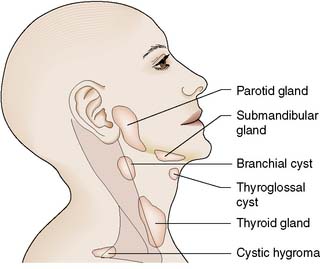

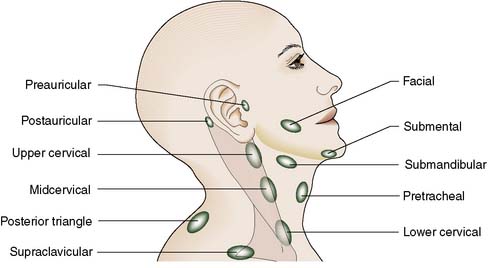

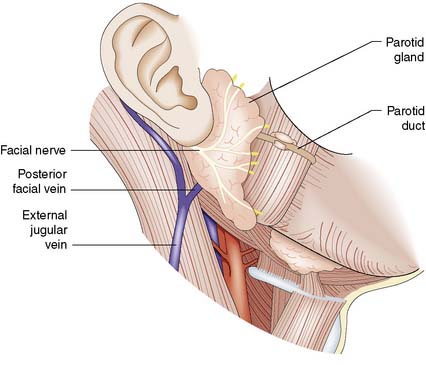

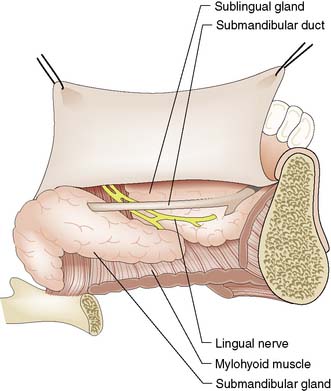

Knowledge of the anatomy of the neck is essential if the likely origin of neck masses is to be determined (Fig. 26.25). In the midline lie the pharynx, larynx and trachea anteriorly. The oesophagus is deep to the trachea. The thyroid gland lies anterior and lateral to the trachea, low in the neck (i.e., confusingly, well below the thyroid cartilage). Laterally, the sternomastoid muscles link the sternum and clavicles inferiorly to the mastoid process superiorly. Between them and the midline, the anterior triangles contain the carotid arteries and jugular veins, with the related vagus nerve. Along the jugular vein is a chain of deep cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 26.26). In the submental region lie the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. The parotid salivary glands lie posterior to the angle of the mandible and anterior to the external auditory meatus (Fig. 26.27). The facial nerve runs through the parotid gland and emerges as a number of branches. The submandibular salivary gland is the second largest major salivary gland and is situated in the floor of the mouth medial to the mandible (Fig. 26.28). Its duct passes anteriorly and opens just below the tip of the tongue. The sublingual salivary gland lies in the floor of the mouth anteriorly, close to the opening of the submandibular duct. The mucosa of the mouth contains numerous small accessory salivary glands.

Assessment

Imaging

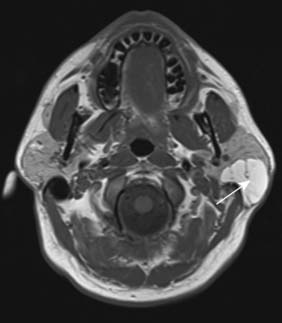

CT can be used to assess most neck masses and will sometimes reveal lymph node swellings that have not been detected clinically. Cystic swellings can be differentiated from solid ones by ultrasound. Plain X-rays can be used to demonstrate salivary calculi (Fig. 26.29). Both CT and MRI are of value in assessing salivary gland swellings (Fig. 26.30). The introduction of contrast into the duct of a salivary gland (sialogram) is occasionally used to confirm the presence of a calculus or to demonstrate inflammatory changes.

Diseases of the neck

Other cystic swellings

Summary Box 26.5 Lymphadenopathy

• Nodes become palpable when their diameter exceeds 1 cm, but impalpable nodes may contain tumour

• Tender nodes are usually inflammatory, whereas non-tender nodes may be malignant

• Painless neck nodes in patients over 45 years of age are often due to metastases from carcinoma. In most cases, the primary is within the head and neck. Such nodes must not be biopsied in the first instance; a thorough search for a primary lesion is the key to diagnosis

• Fine-needle aspiration cytology can be diagnostic for head and neck tumours or lymphoma

• CT defines the extent of the lymphadenopathy in cancer patients

Lymph node swellings

Lymph nodes may become enlarged in response to infection in their area of drainage. Primary neoplasms (lymphomas) and secondary deposits, usually from squamous carcinomas of the head and neck must be considered among the wide differential (Table 26.4). Careful examination of the upper aerodigestive tract is therefore mandatory in assessing an undiagnosed neck node. Direct examination of the oral mucosa is followed by transnasal endoscopic examination of the nose, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and, increasingly, the oesophagus in centres offering transnasal oesophagoscopy. Supplementary palpation of the tonsils and tongue may reveal an occult tumour. If clinical findings are unhelpful the next step depends on the level of suspicion that there is a squamous cancer. PET CT scanning of the neck, fine needle aspiration cytology and rigid endoscopy under general anaesthetic with ipsilateral diagnostic tonsillectomy should all be considered. As a last resort, it may be necessary to excise the swelling for histological examination. However, small mobile lymph node swellings can be observed especially if ultrasound reveals a well preserved length to transverse ratio, i.e. a normal, oval shape. Tumour infiltrated nodes are more typically spherical.

| Infective Bacterial |

Salivary gland tumours

Many different tumours arise in the salivary glands. Commonest are the pleomorphic adenoma (mixed salivary tumour, Fig. 26.31) and the adenolymphoma (Warthin’s tumour). Malignant tumours and others of variable behaviour also occur (Table 26.5). Benign parotid tumours are excised with a cuff of normal tissue (superficial parotidectomy). Care must be taken to avoid damage to the facial nerve, which runs through the gland between the deep and superficial lobes. Submandibular gland tumours are treated by excision of the gland. Malignant tumours are treated by more radical surgery, with or without radiotherapy.

| Benign |

Carotid body tumours

Summary Box 26.6 Salivary gland swellings

• Swellings in the submandibular gland are more often due to calculi, but those in the parotid gland are commonly benign neoplasms

• The most common salivary gland tumours are pleomorphic adenomas

• Parotid swellings generally require removal with a cuff of normal salivary tissue (superficial parotidectomy)

• The facial nerve runs through the parotid gland as a series of branches and is at risk during parotid surgery.