E

Ear, nose and throat surgery (ENT surgery). Procedures vary from minor day-case surgery (e.g. myringotomy) to major head and neck dissections. Anaesthetic considerations:

– airway obstruction may be present (often worse on lying flat), particularly in adults presenting with known or suspected tumours. Flexible nasendoscopy performed in clinic can be a useful source of information regarding the patient’s upper airway anatomy. Potential difficulty with intubation/mask ventilation should be assessed.

– obstructive sleep apnoea (with features of chronic hypoxaemia) may be present.

– specific emergencies include bleeding tonsil, inhaled foreign body, epiglottitis and peritonsillar abscess.

– anxiolytic, analgesic or antisialagogue premedication may be useful depending on the clinical context and intended anaesthetic technique.

– induction appropriate to the patient’s age, co-morbidities, anticipated airway difficulty, etc.

– techniques for securing the airway in potentially difficult cases include:

– direct laryngoscopy under deep inhalational anaesthesia.

– fibreoptic intubation (awake or anaesthetised).

– tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy performed under local anaesthesia.

– options for airway maintenance:

– tracheal tube: traditionally used for most procedures, with a throat pack if bleeding or debris is anticipated. Preformed tubes are useful. Oral intubation is suitable for many procedures, including laryngectomy and tonsillectomy. Nasal intubation provides better surgical access to the oral cavity; topical local anaesthetic agents and vasopressor drugs (e.g. cocaine) are used to reduce nasal bleeding (see Nose). A small-diameter (5 mm) tube, passed orally or nasally, is usually suitable for microlaryngoscopy.

– LMA (flexible/reinforced): avoids problems associated with intubation/extubation but may impair surgical access and be more prone to displacement.

– facemask anaesthesia: suitable for minor ear operations (e.g. myringotomy/grommets).

– injector techniques: often used for bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy, tracheal surgery.

– access to the airway during surgery is restricted, therefore monitoring is particularly important. Obstruction of the airway is possible, especially during tonsillectomy if a mouth gag is used.

– N2O is usually avoided in middle ear surgery, because of expansion of gas-filled cavities.

– surgery involving the face and neck may damage the facial and laryngeal nerves respectively (see Hyperthryoidism). Absence of neuromuscular blockade may be requested by the surgeon in order to allow identification of nerves by electrical stimulation. Spontaneous ventilation, or IPPV using opioids (e.g. remifentanil), a volatile agent and induced hypocapnia, may be employed.

– thoracotomy is occasionally required, e.g. mobilisation of the stomach for anastomosis.

– laser surgery is common, especially for laryngeal surgery.

– adrenaline solutions are often used by the surgeon.

– tracheal extubation is performed with the patient deeply anaesthetised or awake (but not in between, because of the risk of laryngospasm) and in the head-down, lateral position to reduce airway soiling.

postoperatively: as for any surgery. Major procedures may require ICU/IPPV postoperatively.

postoperatively: as for any surgery. Major procedures may require ICU/IPPV postoperatively.

See also, Intubation, difficult; Mandibular nerve blocks; Maxillary nerve blocks

Early warning scores. Simple scoring systems used to aid identification of critically ill patients or those at risk of further clinical deterioration. Several different systems have been described, employing different groups of physiological parameters (e.g. systolic BP, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, neurological status and urine output) that are weighted on the basis of their deviation from a ‘normal’ range. Early warning schemes may be used to ‘trigger’ calls for assistance from the patient’s primary team, a medical emergency team, an outreach team or others. In the UK, the modified early warning score is most commonly used.

Cuthbertson BH, Smith GB (2007). Br J Anaesth; 98: 704–6

See also, Acute life-threatening events – recognition and treatment

East–Freeman automatic vent, see Ventilators

Eaton–Lambert syndrome, see Myasthenic syndrome

right heart failure and cyanosis (due to right-to-left shunting).

right heart failure and cyanosis (due to right-to-left shunting).

tricuspid valve regurgitation.

tricuspid valve regurgitation.

ASD is often present.

ASD is often present.

May lead to arrhythmias, conduction defects (especially the Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome) and sudden death. Surgery may be indicated in severe cases.

[Wilhelm Ebstein (1836–1912), German physician]

ECF, see Extracellular fluid

ECG, see Electrocardiography

Echocardiography. Cardiac imaging using reflection of ultrasound pulses from interfaces between tissue planes. A single beam may be studied as it passes through the heart, displaying movement of tissue planes over time, usually recorded on moving paper (M mode). Alternatively, beams are directed in different directions from the same point, covering a sector of tissue; a moving cross-section may then be displayed on a screen. Analysis of the frequencies of reflected pulses may provide information about the velocity of moving structures and blood flow (Doppler effect); flow characteristics may be colour-coded and superimposed on sector images. The passage of injected saline may be studied as it travels through the heart, probably due to entrainment of small air bubbles.

Useful in diagnosing and quantifying valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, patent foramen ovale, myocardial and pericardial disease, and in assessing myocardial function. Techniques for the latter involve measurement of left ventricular dimensions and provide information about ejection fraction and cardiac output. Doppler techniques may be used to estimate pressure gradients across valves, as the gradient is related to the difference in velocities across the stenosis. Abnormalities of ventricular wall movement may occur in the early stages of myocardial ischaemia, before ECG changes occur.

Transoesophageal echocardiography gives a good view of much of the heart, and has been used perioperatively and in ICU.

Eclampsia. Convulsions caused by hypertensive disease of pregnancy (pre-eclampsia).

complications of pre-eclampsia, especially coagulopathy.

complications of pre-eclampsia, especially coagulopathy.

cerebral oedema/haemorrhage, coma, death.

cerebral oedema/haemorrhage, coma, death.

aspiration of gastric contents, cardiac failure, pulmonary oedema.

aspiration of gastric contents, cardiac failure, pulmonary oedema.

Incidence is 2–3 cases per 10 000 births in the UK. Occurs antepartum in 45% of cases, intrapartum in 20% and postpartum in 35% (usually under 2–4 days postpartum but eclampsia has been reported up to 2–3 weeks afterwards). Only 40% of cases have hypertension and proteinuria in the preceding week, and in many cases premonitory signs of headache, photophobia and hyperreflexia do not precede convulsions, which may recur if untreated. Mortality is almost 2% in the UK, usually from CVA; perinatal mortality is 5–6%. Maternal mortality is up to 25% mortality in developing countries.

anticonvulsant drugs; magnesium sulphate is the drug of choice for treating eclamptic seizures, superseding diazepam and phenytoin that were traditionally used in the UK; it reduces the incidence of recurrent convulsions and of fetal/maternal complications. Thiopental is suitable in resistant cases; tracheal intubation is required.

anticonvulsant drugs; magnesium sulphate is the drug of choice for treating eclamptic seizures, superseding diazepam and phenytoin that were traditionally used in the UK; it reduces the incidence of recurrent convulsions and of fetal/maternal complications. Thiopental is suitable in resistant cases; tracheal intubation is required.

head-down, left lateral position, if the trachea is unprotected.

head-down, left lateral position, if the trachea is unprotected.

Ecothiopate iodide. Organophosphorus compound, used as eye drops to treat severe glaucoma. Plasma cholinesterase levels may be reduced for 3–4 weeks following its use, prolonging the action of suxamethonium.

Ectopic beats, see Atrial ectopic beats; Junctional arrhythmias; Ventricular ectopic beats

ED50, see Therapeutic ratio/index

Edetate, see Cyanide poisoning; Sodium calcium edetate

Edrophonium chloride. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, used to reverse non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade, and in the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis and dual block. Has also been used to treat SVT. Binds reversibly to acetylcholinesterase, with onset of action 30 s and duration of about 5 min. Of faster onset than neostigmine, and with fewer muscarinic side effects.

• Dosage:

reversal of neuromuscular blockade: 0.5–0.7 mg/kg iv with atropine.

reversal of neuromuscular blockade: 0.5–0.7 mg/kg iv with atropine.

differentiation between myasthenic and cholinergic crises: 2 mg iv, 1 h after the last dose of cholinergic drug. Increased muscle strength occurs in myasthenic crisis; worsening of weakness in cholinergic crisis.

differentiation between myasthenic and cholinergic crises: 2 mg iv, 1 h after the last dose of cholinergic drug. Increased muscle strength occurs in myasthenic crisis; worsening of weakness in cholinergic crisis.

diagnosis of dual block: 10 mg iv; causes transient improvement in muscle power.

diagnosis of dual block: 10 mg iv; causes transient improvement in muscle power.

• Side effects: bradycardia, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, increased salivation, muscle fasciculation. Convulsions and bronchospasm may also occur. The ECG should always be monitored when edrophonium is administered, and atropine must always be available.

Efficacy. Maximal effect attainable by a drug; e.g. morphine is more efficacious than codeine. A pure antagonist has an efficacy of zero.

Eicosanoids. Collective term used for products of arachidonic acid metabolism involved in inflammation, immunity and cell signalling. Include:

prostanoids: produced by the cyclo-oxygenase pathway, i.e. prostaglandins, prostacyclin and thromboxanes.

prostanoids: produced by the cyclo-oxygenase pathway, i.e. prostaglandins, prostacyclin and thromboxanes.

leukotrienes produced by the lipoxygenase pathways.

leukotrienes produced by the lipoxygenase pathways.

Eisenmenger’s syndrome. Right-to-left cardiac shunt developing after long-standing left-to-right shunt; shunt reversal occurs because increased pulmonary blood flow results in increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension. Prognosis is poor, since pulmonary hypertension is not affected by surgical correction of the shunt. May follow any left-to-right shunt, although the original description referred to VSD. May occur late in ASD and patent ductus arteriosus.

dyspnoea, effort syncope, angina, haemoptysis.

dyspnoea, effort syncope, angina, haemoptysis.

supraventricular arrhythmias, right ventricular failure, features of pulmonary hypertension.

supraventricular arrhythmias, right ventricular failure, features of pulmonary hypertension.

Anaesthesia is tolerated poorly; reduction in peripheral resistance increases the shunt with worsening hypoxaemia, that in turn further increases pulmonary vascular resistance. Factors that decrease pulmonary blood flow also exacerbate the right-to-left shunt, e.g. IPPV. Risk of systemic air embolism following iv injection of bubbles is high.

Pregnancy is also tolerated badly; maternal mortality is 30–50%. Very cautious epidural anaesthesia has been suggested if pregnancy progresses to term.

Heart–lung transplantation is the only definitive treatment.

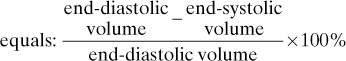

Ejection fraction. Left ventricular stroke volume as a fraction of end-diastolic volume.

Useful as an indication of the heart’s ability to eject stroke volume. Measured using nuclear cardiology, echocardiography, pulmonary artery catheterisation or contrast angiography. Normally greater than 60%. May also be determined for the right ventricle.

Ejector flowmeter. Device used for scavenging from anaesthetic breathing systems. O2 or air passing through the ejector causes entrainment of waste gases by the Venturi principle. The rate of removal is adjusted using a flowmeter until it equals the rate of fresh gas supply. Several litres of driving gas may be required per minute, at a pressure of at least 1 bar.

EKG, see Electrocardiography

Elastance. Reciprocal of compliance. Total elastance for lungs + chest wall is approximately 10 cmH2O/l.

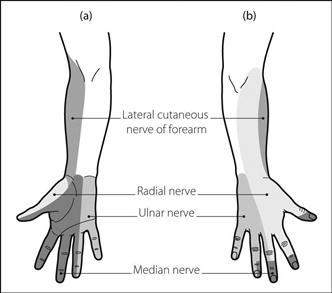

Elbow, nerve blocks. Used for surgery to the hand and wrist; useful for supplementation of a brachial plexus block. May be performed using surface anatomy landmarks, a peripheral nerve stimulator and/or ultrasound guidance.

• The following nerves are blocked (Fig. 57):

median (C5–T1): lies immediately medial to the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa. A needle is inserted with the elbow extended, level with the epicondyles, to approximately 5 mm, and 5 ml local anaesthetic agent injected. Subcutaneous infiltration blocks cutaneous branches.

median (C5–T1): lies immediately medial to the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa. A needle is inserted with the elbow extended, level with the epicondyles, to approximately 5 mm, and 5 ml local anaesthetic agent injected. Subcutaneous infiltration blocks cutaneous branches.

radial (C5–T1): lies in the antecubital fossa in the groove between biceps tendon medially and brachioradialis muscle laterally. A needle is inserted level with the epicondyles with the elbow extended, and directed proximally and laterally to contact the lateral epicondyle. 2–4 ml solution is injected, and a further 5 ml during withdrawal to skin. This is repeated with the needle directed more proximally.

radial (C5–T1): lies in the antecubital fossa in the groove between biceps tendon medially and brachioradialis muscle laterally. A needle is inserted level with the epicondyles with the elbow extended, and directed proximally and laterally to contact the lateral epicondyle. 2–4 ml solution is injected, and a further 5 ml during withdrawal to skin. This is repeated with the needle directed more proximally.

lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (C5–7): lies alongside the radial nerve. It is a continuation of the musculoskeletal nerve of the brachial plexus. May be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration between biceps and brachioradialis, using the same puncture site as for the radial nerve.

lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (C5–7): lies alongside the radial nerve. It is a continuation of the musculoskeletal nerve of the brachial plexus. May be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration between biceps and brachioradialis, using the same puncture site as for the radial nerve.

ulnar (C6–T1): passes through the ulnar groove behind the medial humeral epicondyle. With the elbow flexed to 90°, a fine needle is inserted 1–2 cm proximal to the groove, pointing distally. At 1–2 cm depth, 2–5 ml solution is injected. Neuritis may follow injection into the nerve, or block within the ulnar groove.

ulnar (C6–T1): passes through the ulnar groove behind the medial humeral epicondyle. With the elbow flexed to 90°, a fine needle is inserted 1–2 cm proximal to the groove, pointing distally. At 1–2 cm depth, 2–5 ml solution is injected. Neuritis may follow injection into the nerve, or block within the ulnar groove.

Elderly, anaesthesia for. Increasingly common as the population ages. Mortality and morbidity are higher in older patients.

• Anaesthetic considerations, compared with younger patients:

– ischaemic heart disease is more likely, with reduced ventricular compliance and contractility, and cardiac output.

– decreased blood flow to vital organs.

– cerebrovascular insufficiency is common.

– widespread atherosclerosis with a less compliant arterial system. Hypertension is common.

– veins are more tortuous, thickened and fragile.

– DVT is more common.

– decreased lung compliance and alveolar surface area.

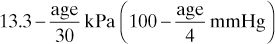

– increased closing capacity, therefore more airway collapse with resultant increase in alveolar–arterial O2 difference. Normal alveolar PO2 is approximately:

– decreased response to hypercapnia and hypoxaemia.

– higher incidence of postoperative atelectasis, PE and chest infection.

– increased sensitivity to many drugs, especially CNS depressants.

– half-lives of many drugs are increased.

– fluid balance is more critical with reduction in total body water; dehydration is common following trauma and illness.

– diabetes mellitus and malnutrition are more common.

– cerebrovascular disease is common.

– confusion and postoperative cognitive dysfunction are more likely, and may be caused by hypoxia, hyperventilation, drugs, hospitalisation and any illness.

– autonomic nervous system dysfunction is common.

– impaired hearing, vision and memory loss are common.

– heat loss during anaesthesia is more likely due to impairment of both central control and compensatory mechanisms.

– hiatus hernia is more common, with risk of regurgitation and aspiration.

– systemic diseases and multiple drug therapy are more common.

In general, patients are frailer, with greater likelihood of perioperative complications and slower healing. Attention to detail (e.g. fluid balance) is more important than with younger patients, since physiological reserves are less. Smaller doses of most agents are required, and arm–brain circulation time is prolonged.

Warming blankets, adequate humidification and appropriate monitoring (e.g. of urine output) should be provided. Postoperative O2 therapy should be instituted immediately and possibly continued for 1–3 days, since hypoxia may readily occur.

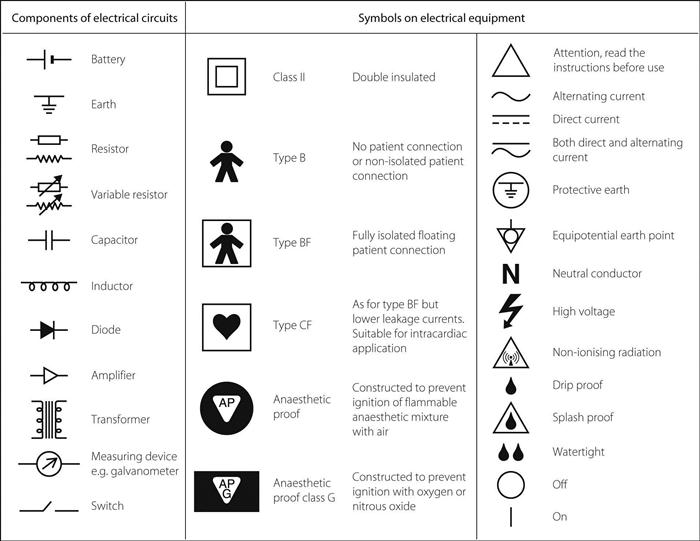

Electrical symbols. Used to denote components of electrical circuits. Specific symbols are also used on electrical equipment to indicate the safety features or other characteristics or instructions (Fig. 58).

See also, Electrocution and electrical burns

Fig. 58 Electrical symbols

Electroacupuncture, see Acupuncture

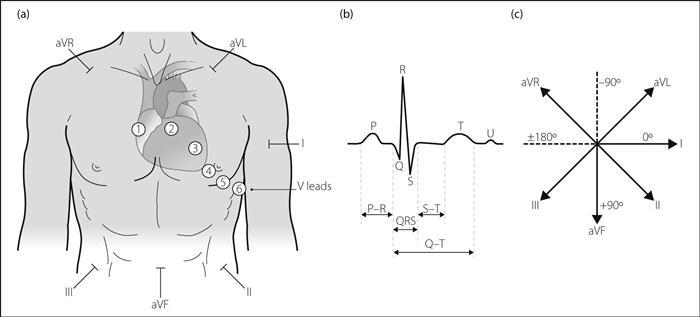

Electrocardiography (ECG). Recording and display of cardiac electrical activity. First performed through the intact chest in 1887 by Waller. Used for investigation of cardiac disease, particularly ischaemic heart disease and arrhythmias, also for monitoring cardiac rhythm.

Standard modern ECG recordings are obtained from different combinations of chest and limb electrodes, each set recording along a different vector, thus providing information about a different part of the heart. A ‘lead’ refers to the recorded voltage difference between two electrodes; one acts as the positive electrode, the other as the negative (or reference) electrode. The limb leads (I–III, aVR, aVL, aVF) record in the frontal plane, the chest leads (V1–6) in the transverse plane. The leads may be represented on the chest and heart as in Figure 59a. Thus abnormalities of the inferior portion of the heart will be demonstrated in the ‘inferior’ leads (i.e. aVF, II and III), and abnormalities of the anterolateral heart in aVL, I, II, etc. V1–2 demonstrate electrical activity from the right side of the heart, V3–4 from the septum and front, and V5–6 from the left side. Depolarisation towards a positive electrode (or repolarisation away) results in a positive deflection; depolarisation away (or repolarisation towards) causes negative deflection.

– I: between left arm (positive electrode) and right arm (negative).

– II: between left leg (positive electrode) and right arm (negative).

– III: between left leg (positive electrode) and left arm.

– V1: fourth intercostal space, right sternal edge.

– V2: fourth intercostal space, left sternal edge.

– V3: midway between V2 and V4.

– V4: fifth intercostal space, left midclavicular line.

Output is displayed on an oscilloscope or recorded on moving paper. Frequency range is 0.5–80 Hz. Magnitude of deflection is proportional to the amount of heart muscle, but reduced by passage through the chest. Skin resistance is reduced by cleaning with alcohol and skin abrasion. Electrodes are usually silver/silver chloride with chloride conducting gel, to reduce generation of potentials in the electrode by the recorded potential, and reduce impedance variability. Electrodes of differing compounds may generate potential by a battery-like effect. Interference may result from muscle activity, radiofrequency waves from diathermy and other equipment and inductance by electrical equipment. Differential amplifiers with common-mode rejection (elimination of signals affecting both input terminals of a recording system) are used to reduce interference.

• Plan for the interpretation of standard ECG, with normal values (Fig. 59b):

patient’s name, clinical context, date.

patient’s name, clinical context, date.

rate: heart rate in beats/min is calculated by dividing the number of 5 mm squares between successive QRS complexes into 300, assuming a recording speed of 25 mm/s.

rate: heart rate in beats/min is calculated by dividing the number of 5 mm squares between successive QRS complexes into 300, assuming a recording speed of 25 mm/s.

– regular or irregular. An irregular rhythm may be regularly (e.g. missing every third QRS) or irregularly irregular (e.g. completely random in AF).

– presence/absence of P waves, flutter waves in atrial flutter, ventricular ectopic beats, pacing spikes, etc.

axis: summation of electrical potentials from the standard and aV leads, plotted as vectors. The normal axis lies between –30° and +90° (Fig. 59c).

axis: summation of electrical potentials from the standard and aV leads, plotted as vectors. The normal axis lies between –30° and +90° (Fig. 59c).

Left axis deviation (< −30°) may occur in:

– normal subjects (especially if pregnant), ascites, etc.

– left bundle branch block, left anterior hemiblock.

– left ventricular hypertrophy.

Right axis deviation (> 90°) may occur in:

– right ventricular hypertrophy.

– right bundle branch block, left posterior hemiblock.

P wave (atrial depolarisation):

P wave (atrial depolarisation):

– positive in I, II, and V4–6; negative in aVR, since depolarisation moves downwards and to the left.

– shape.

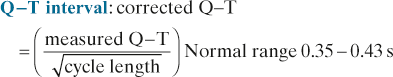

P–R interval: normally 0.12–0.2 s (3–5 mm squares).

P–R interval: normally 0.12–0.2 s (3–5 mm squares).

QRS complex (ventricular depolarisation):

QRS complex (ventricular depolarisation):

– duration is 0.04–0.12 s (1–3 mm squares).

– amplitude in I + II + III > 5 mm. Left ventricular hypertrophy exists if the R wave in V6 + S wave in V1 > 35 mm. In right ventricular hypertrophy the R : S ratio > 1 in V1–2.

– abnormal waves, e.g. J and δ waves in hypothermia and Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome respectively.

– level within 1 mm of baseline.

– shape.

T wave (ventricular repolarisation):

T wave (ventricular repolarisation):

– orientation as for QRS complexes.

– shape.

During anaesthesia/intensive care, a three-electrode system (allowing recording of the three standard limb leads) is often used and lead II is selected for continuous rhythm monitoring. A five-electrode system incorporating a right leg and precordial electrode (in addition to the right arm/left arm/left leg electrodes) enables recording of an anterior chest lead; useful when monitoring left ventricular myocardial ischaemia. The CM5 lead configuration (central manubrium V5) also ‘looks at’ the left ventricle:

right arm electrode in suprasternal notch.

right arm electrode in suprasternal notch.

left arm electrode over apex of heart (V5 position).

left arm electrode over apex of heart (V5 position).

left leg electrode on left shoulder or leg serves as ground.

left leg electrode on left shoulder or leg serves as ground.

See also, Cardiac cycle; Heart block: His bundle electrography; Myocardial infarction

– concurrent drug therapy may include antidepressant drugs, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors, lithium.

– premedication is usually omitted.

– monitoring is required as for any procedure.

– a single induction dose of iv agent is usually given. Methohexital was traditionally used because of its short action and pro-convulsant properties. Propofol (at 1 mg/kg) provides greater haemodynamic stability and more rapid post-ictal recovery whilst having the same therapeutic benefit as methohexital and has become the induction agent of choice.

– suxamethonium 0.5 mg/kg is commonly given, although smaller doses have been used.

– a soft mouth guard is inserted to protect the teeth and gums.

– intense parasympathetic discharge may follow passage of current, and may be followed by increased sympathetic activity. Atropine should always be available; routine administration has been suggested.

Electrocution and electrical burns. Hazard of using electrical equipment; during anaesthesia, malfunction or improper use of diathermy, monitoring equipment or infusion devices may cause sudden cardiac arrest or burns.

• Effects:

heat production due to high resistance of tissues. Amount of heat is related to current density. May produce burns at sites of current entry/departure.

heat production due to high resistance of tissues. Amount of heat is related to current density. May produce burns at sites of current entry/departure.

nerve and muscle stimulation; e.g. effect of current across chest (approximate values):

nerve and muscle stimulation; e.g. effect of current across chest (approximate values):

– 15 mA: tonic muscle contraction, i.e. ‘can’t let go’ threshold.

– > 5 A: tonic contraction of the myocardium (utilised in defibrillation).

– frequency of alternating current: 50–60 Hz is particularly dangerous but cheap to provide.

– timing of shock (e.g. R on T phenomenon).

regular checking and maintenance of electrical equipment.

regular checking and maintenance of electrical equipment.

use of batteries only (impractical).

use of batteries only (impractical).

double insulation of all conducting wires within equipment (class II).

double insulation of all conducting wires within equipment (class II).

reduction of stray leakage currents, e.g. due to drops in potential along the length of conductors, caused by capacitance between casing and innards or inductance. Leakage currents may be sufficient to produce microshock. Earth conductors are connected to each other to reduce differences between them. Current-operated earth-leakage circuit breakers may be used. Standards for leakage currents are defined, e.g. 10 µA maximum from the casing or delivered to the patient for intracardiac equipment; 100–500 µA for other equipment, depending on usage.

reduction of stray leakage currents, e.g. due to drops in potential along the length of conductors, caused by capacitance between casing and innards or inductance. Leakage currents may be sufficient to produce microshock. Earth conductors are connected to each other to reduce differences between them. Current-operated earth-leakage circuit breakers may be used. Standards for leakage currents are defined, e.g. 10 µA maximum from the casing or delivered to the patient for intracardiac equipment; 100–500 µA for other equipment, depending on usage.

Medical electrical equipment is marked with the appropriate electrical symbols to indicate its level of safety features (see Fig. 58).

beta: normal 13–30 Hz waves. Prominent over the frontal area during the awake and active state.

beta: normal 13–30 Hz waves. Prominent over the frontal area during the awake and active state.

As age increases, infantile beta activity is slowly replaced by adult alpha activity. Characteristic patterns occur in normal sleep. During anaesthesia, alpha rhythms become depressed, and are replaced by theta and delta rhythms. Slow rhythms may reappear at deeper levels of anaesthesia, followed by periods of little or no activity separated by bursts of activity (burst suppression). The pattern differs with different agents used. Perioperative use is limited by electrical interference, difficult interpretation and production of large amounts of paper. Modified forms of EEG have therefore been developed, e.g. cerebral function monitor, cerebral function analysing monitor, power spectral analysis, bispectral index monitor. Used to investigate intracranial activity in, e.g., head injury, epilepsy, cerebrovascular disease, coma, encephalopathies, surgery. Similar principles are involved in measuring evoked potentials.

Electrolyte. Compound that dissociates in solution to produce ions, allowing conduction of electricity; also refers to the ions themselves. Sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium and hydrogen ions are the most important cations in the body; chloride and bicarbonate ions the most important anions.

Electrolyte imbalance, see individual disorders

Electrolyte solutions, see Intravenous fluids

Electromechanical dissociation (EMD). Term used to describe a cardiac state in which organised electrical depolarisation occurs throughout the myocardium, but there is no synchronous shortening of the myocardial fibres and mechanical contractions are absent. Part of the spectrum of pulseless electrical activity, though the latter also includes mechanical contractions too weak to produce a detectable cardiac output.

Electromyography (EMG). Recording of spontaneous or evoked electrical activity from skeletal muscle; usually combined with nerve conduction studies that measure the velocity of nerve conduction following stimulation at different sites along a nerve pathway. Thus useful in distinguishing between disorders of muscle, isolated or generalised nerve disease or lesions, and disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction.

In anaesthesia, it has been used to determine frontalis muscle tone to monitor depth of anaesthesia. Also used in neuromuscular blockade monitoring; nerve stimulation and muscle action potential recording are achieved using surface skin electrodes, although needle electrodes have been used. Less convenient than devices measuring mechanical muscle response, it may detect electrical activity when mechanical contraction is undetectable.

Is also used to investigate critical illness polyneuropathy and the neuromuscular function of the eye, bladder, GIT, etc.

Electron capture detector. Device used in the analysis of gas mixtures that have been separated by, for example, gas chromatography; particularly useful in detecting halogenated compounds. Electrons within an ionisation chamber pass from cathode to anode, but are ‘captured’ by the halogenated substance blown through the chamber. The current passing across the chamber is therefore reduced, depending on how many electrons are captured. Used to quantify the amount of known substances, not to identify unknown ones.

Emergence phenomena. Usually consist of agitation and confusion, with laryngospasm, breath-holding, etc.; may be equivalent to the second stage of anaesthesia seen on induction, or be due to other causes of confusion, including the central anticholinergic syndrome and dystonic reactions. Hallucinations and frightening dreams are common after ketamine.

inadequate preparation of patients for surgery:

inadequate preparation of patients for surgery:

full stomach, i.e. risk of aspiration of gastric contents.

full stomach, i.e. risk of aspiration of gastric contents.

untreated pre-existing disease, electrolyte imbalance, etc.

untreated pre-existing disease, electrolyte imbalance, etc.

appropriate investigations and cross-matching of blood not performed or not ready.

appropriate investigations and cross-matching of blood not performed or not ready.

– haemorrhage and hypovolaemia.

– intestinal obstruction/intra-abdominal pathology: dehydration and hypovolaemia, electrolyte imbalance, etc. Further risk of aspiration due to delayed gastric emptying and vomiting/haematemesis.

– trauma: haemorrhage, head injury, chest trauma, etc.

– airway obstruction/inhaled foreign body.

– related to specialist surgery, e.g. cardiac surgery, neurosurgery.

The balance between the need for preoperative treatment and urgency of surgery is sometimes difficult, but inadequate preoperative correction of fluid and electrolyte disturbance is consistently associated with increased perioperative mortality. Treatment of cardiac failure is also important whenever possible. Careful preoperative assessment and discussion with the surgeon are vital. Anaesthetic management is as for routine surgery but with the above considerations. Thus smaller doses of drugs than usual are given initially. Rapid sequence induction is usually employed. Measures against heat loss are important. Invasive monitoring and postoperative HDU/ICU and IPPV should be considered.

Regional techniques are particularly useful for limb surgery, but epidural/spinal anaesthesia is hazardous if hypovolaemia is present.

Special Issue (2013). Anaesthesia; 68 s1: 1–124

See also, specific procedures; Anaesthetic morbidity and mortality

Emetic drugs. Given to empty the stomach, e.g. following poisoning, or preoperatively to reduce risk of aspiration pneumonitis. Now rarely used, because of poor efficacy and the risk of causing aspiration; particularly dangerous after ingestion of corrosive or petroleum derivatives, or in unconscious patients. Include apomorphine and ipecacuanha; copper sulphate and sodium chloride are no longer used.

EMG, see Electromyography

EMLA cream (Eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics). Mixture of prilocaine base 2.5% and lidocaine base 2.5% as an oil–water emulsion. The melting point of each local anaesthetic agent is lowered by the presence of the other; the resultant mixture has a melting point of 18°C and is effective in providing analgesia of the skin 60–90 min after topical application and covering with an occlusive dressing. May continue to be released from skin depots even after removal of surface cream. Particularly useful in children. May produce blanching of the skin; increases in methaemoglobin have been reported several hours after application.

EMO inhaler, see Vaporisers

Emphysema, see Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Emphysema, subcutaneous. Presence of gas in subcutaneous tissues.

pneumothorax or rupture of a viscus, e.g. oesophagus.

pneumothorax or rupture of a viscus, e.g. oesophagus.

infection with gas-producing organisms, e.g. gas gangrene.

infection with gas-producing organisms, e.g. gas gangrene.

rarely, deliberate self-injection of subcutaneous air in disordered mental states.

rarely, deliberate self-injection of subcutaneous air in disordered mental states.

Empyema. Collection of pus within the pleural cavity. A complication of chest trauma (especially if haemothorax was present), pneumonia, chest drainage, thoracic surgery and subdiaphragmatic abscess. Clinical features include pyrexia, chest pain and productive cough. CXR features are those of a pleural effusion; if encapsulated it may resemble a pulmonary cyst. Diagnosis is confirmed by imaging and aspiration of pus. Treatment depends on aetiology but includes antibacterial drugs, chest drainage (sometimes requiring ultrasound or CT scan guidance) and surgery. May rarely lead to bronchopleural fistula.

Enalapril maleate. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, used to treat hypertension and cardiac failure (including following MI). A prodrug, it is converted to enalaprilat by hepatic metabolism. Longer acting than captopril, with onset of action within 2 h; half-life is up to 35 h via active metabolites.

Encephalitis. Acute infection of the brain parenchyma, usually caused by a virus, that results in diffuse inflammation affecting the meninges. Usually presents with the triad of fever, headache and altered mental status. Other clinical features include neck stiffness, lethargy, confusion, coma, encephalopathy, focal neurological signs and epilepsy.

• Causes:

autoimmune encephalitis (including anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and anti-voltage-gated potassium channel encephalitis) is being increasingly recognised; presents with psychiatric, epileptic and movement disorder features.

autoimmune encephalitis (including anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and anti-voltage-gated potassium channel encephalitis) is being increasingly recognised; presents with psychiatric, epileptic and movement disorder features.

Differential diagnosis includes meningitis and cerebral abscess. Investigations include CSF examination (mild increase in protein, lymphocytosis, normal glucose in viral encephalitis), CT and MRI scanning, EEG and viral titres/cultures from blood and CSF. Treatment is largely supportive, with tracheal intubation and IPPV for patients with depressed consciousness. Aciclovir should be given to all cases of suspected viral encephalitis whilst a definitive diagnosis is sought.

Encephalopathy. Diffuse disorder of cerebral function with or without focal neurological deficit. Usually results in delirium, stupor and coma. Aetiology is as for coma.

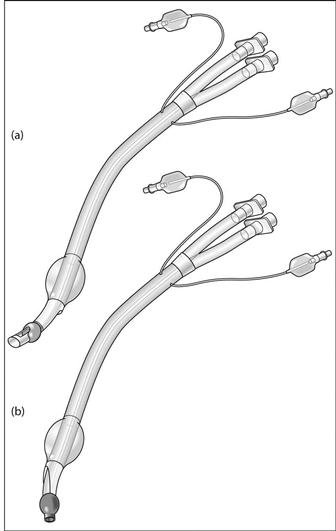

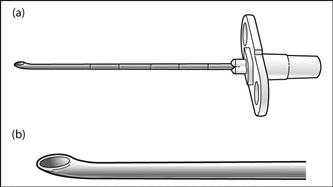

Endobronchial blockers (Bronchial blockers). Used in thoracic surgery to isolate a portion of lung, e.g. to avoid air leaks during IPPV or prevent contamination of normal lung with secretions, pus or blood. Less often used now, except for paediatric surgery, endobronchial tubes being more popular and versatile. Previous versions were made of red rubber; modern versions are thin plastic catheters with an inflatable distal cuff, usually inserted under direct vision via a bronchoscope, either before tracheal intubation with a standard tracheal tube or after intubation with a specific tube–blocker combination.

Endobronchial tubes. Used in thoracic surgery to allow sleeve resection of the bronchus, or to isolate infected lung or potential air leak, e.g. in bronchopleural fistula or emphysematous lung cysts. Other pulmonary surgery (e.g. pneumonectomy/lobectomy, pleural, aortic, oesophageal and mediastinal surgery) is possible with conventional tracheal tubes, although surgery may be made easier by collapsing one lung. Also used in ICU in patients with severe, unilateral lung injury or bronchopleural fistula. Risks of one-lung anaesthesia should be considered before use.

Different tubes, usually made of red rubber, were developed in the 1930s–1950s, and included single-lumen and double-lumen designs, for insertion into the left (most commonly) or right main bronchus. Modern double-lumen tubes are usually plastic, with thinner walls and low-pressure cuffs, and have the following features (Fig. 60):

oropharyngeal portion, concave anteriorly.

oropharyngeal portion, concave anteriorly.

– the catheter mount to the tracheal lumen is clamped, and the tracheal lumen opened to air.

– the tracheal lumen is reconnected and both sides of the chest are checked as before.

Complications are as for tracheal intubation (see Intubation, complications of). Bronchial rupture may occur if excessive volumes are used for cuff inflation. Incorrect positioning, or movement during positioning of the patient, may result in uneven ventilation and impaired gas exchange.

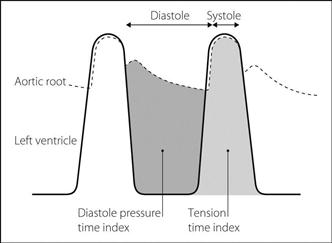

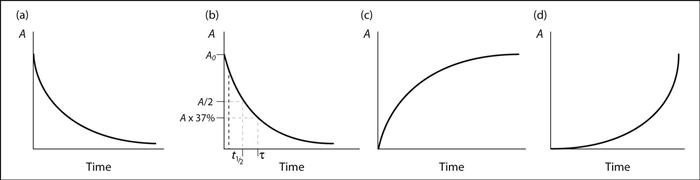

Endocardial viability ratio (EVR). Ratio of diastolic pressure time index to tension time index, obtained by recording left ventricular and aortic root pressure tracings (Fig. 61). May indicate myocardial O2 supply/demand ratio and likelihood of myocardial ischaemia (thought to be likely when the ratio is under 0.7).

Endocarditis, infective. Infective inflammation of the endocardial lining of the heart and valves, most commonly the aortic valve (previously the mitral valve). Commonly associated with abnormal valves (e.g. rheumatic, degenerative or prosthetic valves) or congenital heart disease, but approximately 50% of cases involve normal valves. Men are twice as commonly affected. Nosocomial endocarditis may result from catheter-related sepsis or invasive procedures (e.g. endoscopy, dental extractions). Results in tissue destruction and vegetations of platelets, macrophages and organisms, with systemic embolisation. Systemic immune complex deposition may also occur. Overall mortality is ~40%.

• Traditionally divided into acute and subacute, although definitions are imprecise:

– usually due to virulent organisms, e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus.

– presents early with rapid progression to death unless early aggressive treatment is instituted.

– usually due to Streptococcus viridans or enterococci.

– underlying structural heart disease or presence of prosthetic valves is usual.

– chronic malaise and slow course of disease are typical.

fever (90%), malaise, weight loss, night sweats, anaemia.

fever (90%), malaise, weight loss, night sweats, anaemia.

heart murmurs (85%), cardiac failure, valve lesions.

heart murmurs (85%), cardiac failure, valve lesions.

peripheral embolisation/vasculitic phenomena, e.g. splinter haemorrhages in nail beds, conjunctivae and retina (Roth spots), painful fingertip swellings (Osler’s nodes), painless haemorrhagic lesions on palms and soles (Janeway lesions), kidneys (causing haematuria), CNS (causing CVA). Splenomegaly and clubbing may occur.

peripheral embolisation/vasculitic phenomena, e.g. splinter haemorrhages in nail beds, conjunctivae and retina (Roth spots), painful fingertip swellings (Osler’s nodes), painless haemorrhagic lesions on palms and soles (Janeway lesions), kidneys (causing haematuria), CNS (causing CVA). Splenomegaly and clubbing may occur.

echocardiography (initially transthoracic then transoesophageal if the former is negative).

echocardiography (initially transthoracic then transoesophageal if the former is negative).

European Society of Cardiology Task Force (2009). Eur Heart J; 30: 2369–413

Endocrine disorders, see individual diseases

Endomorphins. Endogenous opioid peptides for µ opioid receptors. Produce spinal and supraspinal analgesia experimentally; have been found in the human brain, although their role is uncertain.

Endorphins. Endogenous opioid peptides derived from β-lipotropin, secreted by the anterior pituitary and hypothalamus. β-Endorphin (31 amino acids) is the most potent endogenous opioid, active mainly at µ and δ opioid receptors. Also inhibits GABA and promotes dopamine secretion. Derived from pro-opiomelanocortin (99 amino acids), from which ACTH is derived. Thought to be involved in central pain pathways, emotion, etc. May also be involved in haemorrhagic and septic shock; thought to reduce SVR, cardiac output and BP, while decreasing GIT motility and sympathetic activity and enhancing parasympathetic activity. This may explain why naloxone sometimes improves cardiovascular variables in shock.

Endothelin. Vasoconstrictor peptide derived from vascular endothelium, involved in regulation of basal vascular tone and BP. Produced from an inactive precursor, it acts at specific endothelin receptors to cause vasoconstriction (type A receptors). Type B receptor activation may also result in production of nitric oxide and prostacyclin. May be involved in local blood flow and in various cardiovascular disorders, notably cardiac failure and pulmonary hypertension. Endothelin receptor antagonists such as bosentan (which antagonises both A and B receptors) have been investigated as possible treatments for these.

Endothelium-derived relaxing factor, see Nitric oxide

Endotoxins. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) present on the surface of Gram-negative bacteria. LPS consist of: a lipid chain (lipid A), responsible for the biological effects; a core polysaccharide; and oligosaccharide side chains specific to each strain. Released when the bacteria die, and extremely toxic, probably via release and activation of many inflammatory substances, including cytokines. Endotoxaemia may be involved in the aetiology of sepsis, although it may occur in the absence of infection, and proven Gram-negative sepsis may not be accompanied by endotoxaemia. Translocation of GIT organisms or their endotoxins into the bloodstream across the gut wall has been suggested to occur in critical illness. Attempts have been made to prevent endotoxaemia by killing GIT organisms (selective decontamination of the digestive tract), and to treat established endotoxaemia with anti-endotoxin antibodies.

Wendel M, Paul R, Heller AR (2007). Intensive Care Med; 33: 25–35

Endotracheal tubes, see Tracheal tubes

End-plate potentials. Depolarisation potentials produced at the postsynaptic motor end-plate of the neuromuscular junction by binding of acetylcholine (ACh) to receptors. Their size and duration depend on the amount of ACh released, the number of ACh receptors free and the activity of acetylcholinesterase. Miniature end-plate potentials (under 1 mV) are thought to be produced by random release of ACh from single vesicles (quantal theory), and are too small to initiate muscle contraction. Simultaneous release of ACh from many vesicles follows depolarisation of the pre-synaptic membrane; the resultant large end-plate potential causes depolarisation of adjacent muscle membrane, and muscle contraction.

End-tidal gas sampling. Gives the approximate composition of alveolar gas, unless major  mismatch exists or tidal volume is very small. Useful for estimating alveolar and hence arterial PCO2, e.g. for monitoring adequacy of ventilation. Alveolar concentrations of inhalational anaesthetic agents may also be monitored. May also indicate extent and rate of uptake of inhalational agents, if expired and inspired concentrations are compared, and the state of O2 supply/demand. On-line multiple gas monitors are now routine, providing breath-by-breath measurements. Since the gas sampled by these is not strictly end-tidal, the sampling line being placed some distance away from the patient’s airway, the term ‘end-expiratory’ is more accurately applied. Mixing of end-expiratory gas with fresh gas may lead to inaccuracy, especially if samples are taken between the breathing system filter and the anaesthetic machine.

mismatch exists or tidal volume is very small. Useful for estimating alveolar and hence arterial PCO2, e.g. for monitoring adequacy of ventilation. Alveolar concentrations of inhalational anaesthetic agents may also be monitored. May also indicate extent and rate of uptake of inhalational agents, if expired and inspired concentrations are compared, and the state of O2 supply/demand. On-line multiple gas monitors are now routine, providing breath-by-breath measurements. Since the gas sampled by these is not strictly end-tidal, the sampling line being placed some distance away from the patient’s airway, the term ‘end-expiratory’ is more accurately applied. Mixing of end-expiratory gas with fresh gas may lead to inaccuracy, especially if samples are taken between the breathing system filter and the anaesthetic machine.

Energy. Capacity to perform work, whether mechanical, chemical or electrical. Kinetic energy is the energy of a body due to its motion; potential energy is the energy of a body due to its state or position. Thus a body on a table has potential energy due to the effect of gravity; when it falls, this is converted to kinetic energy. Similarly, the potential energy of a stretched spring is converted to kinetic energy as it recoils. The law of conservation of energy states that energy cannot be destroyed or created, but only converted to other forms of energy, e.g. heat, light, sound. Molecules within a body have potential energy due to their chemical composition and forces between them, and kinetic energy due to their movement. SI unit is the joule, although the Calorie (Cal; equals 1000 cal) is widely used for dietary energy estimations.

Energy is liberated in the body by breakdown of metabolic substrates, e.g. approximately 4 Cal/g carbohydrate and protein, 9 Cal/g fat, 7 Cal/g alcohol. It may be stored in high phosphate bonds, e.g. in ATP, and in other compounds, e.g. glycogen.

Energy balance. Difference between Calorie intake and energy output. If intake is less than expenditure, energy balance is negative and endogenous energy stores are utilised; if it is greater, balance is positive and the individual gains weight. Many critically ill patients (e.g. those with trauma, sepsis) have increased catabolism and glycogenolysis, insulin resistance with resultant lipolysis and increased basal metabolic rate. In order to provide adequate nutrition in these patients, it is possible to estimate energy expenditure, e.g. with indirect calorimetry using bedside devices (‘metabolic carts’). This allows measurement of O2 and CO2 exchange and thus respiratory exchange ratio; however such techniques are not widely used because of inaccuracies related to gas leaks from the patient/ventilator circuit and the effect of water vapour.

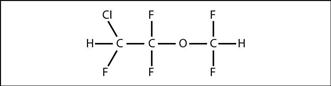

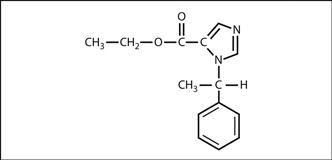

Enflurane. 2-Chloro-1,1,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether (Fig. 62). Inhalational anaesthetic agent, introduced in 1966.

colourless volatile liquid with ether-like smell; vapour is 7.5 times denser than air.

colourless volatile liquid with ether-like smell; vapour is 7.5 times denser than air.

SVP at 20°C 24 kPa (175 mmHg).

SVP at 20°C 24 kPa (175 mmHg).

MAC 1.7% (middle age); 1.9% (young adults); 2.4–2.5% in children/teenagers.

MAC 1.7% (middle age); 1.9% (young adults); 2.4–2.5% in children/teenagers.

non-flammable and non-corrosive. Stable without additives and unaffected by light.

non-flammable and non-corrosive. Stable without additives and unaffected by light.

• Effects:

– smooth and rapid induction and recovery.

– epileptiform EEG activity may occur (typically a three per second spike and wave pattern), especially at doses > 2 MAC with coexisting hypocapnia. Convulsions may occur postoperatively.

– increased cerebral blood flow but reduced intraocular pressure.

– depresses airway reflexes less than halothane and therefore tracheal intubation is more difficult when the patient is breathing spontaneously.

– causes greater respiratory depression than halothane or isoflurane; an increased respiratory rate is common, with decreased tidal volume.

– causes fewer arrhythmias than halothane, and less sensitisation of the myocardium to catecholamines.

– dose-dependent uterine relaxation.

About 2% metabolised, the rest excreted via the lungs. Although fluoride ions may be produced by metabolism, toxic levels are usually not reached, although they have been reported in obese patients after prolonged anaesthesia. Patients with pre-existing renal impairment or receiving other nephrotoxic drugs or enzyme-inducing drugs, e.g. isoniazid, are also thought to be at risk.

Hepatitis has been reported following enflurane; cross-sensitivity with halothane has been suggested, but this is disputed.

Fig. 62 Structure of enflurane

Enkephalins. Endogenous opioid peptides found in the CNS, especially:

Methionine enkephalin and leucine enkephalin (each 5 amino acids) are derived from proenkephalin; they are thought to be involved in the modulation of pain pathways, e.g. gate control theory of pain. Active mainly at δ opioid receptors.

Enoxaparin, see Heparin

Enoximone. Selective (PDE III) phosphodiesterase inhibitor unrelated to catecholamines or cardiac glycosides. Used as an inotropic drug, particularly in cardiogenic or other types of shock, in which there is an element of heart failure (e.g. after cardiac surgery, and in patients awaiting heart transplants). Increases cardiac contractility and stroke volume with minimal tachycardia, and without increasing myocardial O2 demand. Also causes vasodilatation (reducing both preload and afterload), thereby decreasing ventricular filling pressures. BP may fall.

Acts directly on cardiac muscle rather than adrenergic (or other) receptors.

Undergoes hepatic metabolism to partially active metabolites, excreted renally.

ENT surgery, see Ear, nose and throat surgery

Enteral nutrition, see Nutrition, enteral

Entonox. Trade name for gaseous N2O/O2 50 : 50 mixture, supplied in cylinders at a pressure of 137 bar. Invented by Tunstall in 1962. Cylinders are coloured blue with blue/white quartered shoulders. May also be supplied by pipeline. Formed by bubbling O2 through liquid N2O (Poynting effect).

Cylinders must be kept above –7°C (pseudocritical temperature) to prevent liquefaction of the N2O (a process called lamination). If this occurs and gas is drawn from the top of the cylinder, O2 will be delivered first, followed by almost pure N2O. In the large cylinders used for connection to a pipeline system via a manifold, gas is therefore drawn first from the bottom of the cylinder by a tube; should liquefaction of N2O now occur, N2O containing about 20% O2 is delivered first. Warming and repeated inversion of the cylinders will reconstitute the gaseous mixture.

Widely used for inhalational analgesia for trauma and minor procedures, e.g. physiotherapy or change of dressings; most commonly used with a demand valve for self-administration. Onset of analgesia is rapid, with minimal cardiovascular, respiratory or neurological side effects. Should sedation occur, the patient reduces the intake and recovery rapidly occurs. Caution is required if the patient has an undrained pneumothorax, as N2O may increase its size.

Continuous use (e.g. in ICU) has declined because of interaction of N2O with the methionine synthase system.

Envenomation, see Bites and stings

Environmental impact of anaesthesia. Has attracted increasing attention through two main areas:

Suggested measures to minimise the above include:

increased recycling, including glass from ampoules.

increased recycling, including glass from ampoules.

power-saving strategies, e.g. turning off equipment not in use.

power-saving strategies, e.g. turning off equipment not in use.

avoidance of N2O, use of low-flow systems.

avoidance of N2O, use of low-flow systems.

consideration of transportation costs when ordering equipment/drugs.

consideration of transportation costs when ordering equipment/drugs.

Sneyd JR, Montgomery H, Pencheon D (2010). Anaesthesia; 65; 435–7

Environmental safety of anaesthetists. Hazards faced may be due to:

inhalational agents: fears were expressed, especially in the 1960s, because of reported high incidence of lymphoid tumours in anaesthetists. Chronic exposure to low concentrations of volatile agent was thought to be responsible, hence attempts to remove it from the immediate atmosphere by adsorption or scavenging. Such an association was not supported by subsequent studies, and effects of breathing small amounts of volatile agents are thought to be minimal, if any. Effects of N2O are now considered potentially more harmful; increased incidence of spontaneous abortion and possibly congenital malformation in theatre workers or their spouses is suspected but has never been conclusively proven. This may be via methionine synthase inhibition.

inhalational agents: fears were expressed, especially in the 1960s, because of reported high incidence of lymphoid tumours in anaesthetists. Chronic exposure to low concentrations of volatile agent was thought to be responsible, hence attempts to remove it from the immediate atmosphere by adsorption or scavenging. Such an association was not supported by subsequent studies, and effects of breathing small amounts of volatile agents are thought to be minimal, if any. Effects of N2O are now considered potentially more harmful; increased incidence of spontaneous abortion and possibly congenital malformation in theatre workers or their spouses is suspected but has never been conclusively proven. This may be via methionine synthase inhibition.

Effect on performance is controversial; there is no conclusive evidence that the low atmospheric concentrations measured are deleterious. Any risks are reduced by scavenging, avoiding spillage, monitoring contamination levels and testing apparatus for leaks. Workplace exposure limits set out in COSHH regulations for Great Britain and Northern Ireland are 100 ppm N2O, 50 ppm enflurane/isoflurane and 10 ppm halothane (each over an 8-h period). In the USA, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has recommended an 8-h time-weighted average limit of 2 ppm for halogenated anaesthetic agents in general (0.5 ppm together with exposure to N2O).

infection, e.g. with hepatitis or HIV infection. Risks are reduced by immunisation against hepatitis B, wearing of gloves and goggles, avoidance of needles wherever possible, and careful disposal of any contaminated equipment. Needles should never be resheathed by holding their cover in one’s hand. Devices for safe handling of used needles (e.g. non-removable caps or cannulae/syringes with self-retracting needles) became mandatory in the USA in 2001, with European legislation introduced in 2006. In case of accidental needlestick injuries:

infection, e.g. with hepatitis or HIV infection. Risks are reduced by immunisation against hepatitis B, wearing of gloves and goggles, avoidance of needles wherever possible, and careful disposal of any contaminated equipment. Needles should never be resheathed by holding their cover in one’s hand. Devices for safe handling of used needles (e.g. non-removable caps or cannulae/syringes with self-retracting needles) became mandatory in the USA in 2001, with European legislation introduced in 2006. In case of accidental needlestick injuries:

– testing for HIV and hepatitis infection requires informed patient consent and counselling, a cause of much controversy should a healthcare worker suffer a needlestick injury from an unconscious patient. If considered necessary, PEP with 2–3 antiretroviral agents (including zidovudine) started within 72 h after exposure and continued for 28 days is recommended. PEP reduces the risk of infection by 80%. Follow-up HIV serology testing should be performed at 1, 3 and 6 months.

Risk of infection after accidental exposure of healthcare workers is estimated at 0.3% for HIV (needlestick; higher risk after conjunctival inoculation), 3% for hepatitis C and up to 30% for hepatitis B. Risk is affected by the number of viral particles inoculated and the route. Other more contagious infections: deaths were reported following exposure to patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome.

risk of electrocution and burns, explosions and fires, radiation exposure, back injury, stress and fatigue. Access to addictive drugs makes abuse of anaesthetic agents easier. Alcohol abuse is common among doctors. Increased risk of suicide is suspected, but not proven.

risk of electrocution and burns, explosions and fires, radiation exposure, back injury, stress and fatigue. Access to addictive drugs makes abuse of anaesthetic agents easier. Alcohol abuse is common among doctors. Increased risk of suicide is suspected, but not proven.

Similar concerns exist for staff on the ICU.

Andersen MP, Nielsen OJ, Wallington TJ (2012). Anesth Analg; 114: 1081–5

See also, Contamination of anaesthetic equipment; COSHH regulations

• Classified according to the reaction catalysed:

oxidoreductases: oxidation/reduction, e.g. metabolism of many drugs.

oxidoreductases: oxidation/reduction, e.g. metabolism of many drugs.

transferases: transfer of groups between molecules, e.g. transaminases.

transferases: transfer of groups between molecules, e.g. transaminases.

hydrolases: hydrolytic cleavage or reverse, e.g. acetylcholinesterase.

hydrolases: hydrolytic cleavage or reverse, e.g. acetylcholinesterase.

isomerases: intramolecular rearrangements, e.g. mutases.

isomerases: intramolecular rearrangements, e.g. mutases.

ligases: reactions involving high-energy bonds, e.g. ATP, and formation of C–C, C–N, etc.

ligases: reactions involving high-energy bonds, e.g. ATP, and formation of C–C, C–N, etc.

See also, Enzyme induction/inhibition; Michaelis–Menten kinetics

• May affect metabolism of the original drug and other drugs, leading to drug interactions, e.g.:

– barbiturates increase metabolism of warfarin, phenytoin and chlorpromazine.

– phenytoin increases metabolism of digitoxin, thyroxine, vecuronium, pancuronium and tricyclic antidepressants.

– alcohol increases metabolism of warfarin, barbiturates and phenytoin.

– smoking increases metabolism of vecuronium, pancuronium, morphine, aminophylline, chlorpromazine and phenobarbital.

– ecothiopate reduces metabolism of suxamethonium.

– metronidazole reduces metabolism of acetaldehyde produced by alcohol metabolism.

– cimetidine reduces metabolism of lidocaine, morphine, pethidine, labetalol, propranolol and nifedipine.

Ephedrine hydrochloride. Sympathomimetic and vasopressor drug, mainly used to treat hypotension (especially in spinal and epidural anaesthesia). Sometimes used in the treatment of bronchospasm and autonomic neuropathy.

• Actions:

directly stimulates α- and β-adrenergic receptors.

directly stimulates α- and β-adrenergic receptors.

releases noradrenaline from nerve endings.

releases noradrenaline from nerve endings.

• Effects:

increased heart rate, myocardial contractility and BP.

increased heart rate, myocardial contractility and BP.

CNS arousal and pupillary dilatation.

CNS arousal and pupillary dilatation.

• Dosage:

Tachyphylaxis occurs with repeated administration. May cause restlessness and palpitations in overdose.

Epidural anaesthesia. Introduction of local anaesthetic agent into the epidural space in order to induce loss of sensation adequate for surgery (the term ‘epidural analgesia’ refers to provision of pain relief, e.g. during labour). Can be divided anatomically into cervical, thoracic, lumbar and caudal. Caudal analgesia was first performed in 1901; lumbar blockade was performed by Pages in 1921 and popularised by Dogliotti in the 1920s–1930s, although it was probably introduced by Corning following his initial experiments. Continuous catheter techniques were introduced in the late 1940s.

Following injection, local anaesthetic may act at epidural, paravertebral or subarachnoid nerve roots, or directly at the spinal cord. Systemic effects may also occur.

Indications are as for spinal anaesthesia; main advantages are avoidance of dural puncture, and those related to catheter technique, i.e. allows control over onset, extent and duration of blockade. Thus used for peri- and postoperative analgesia, analgesia following chest trauma, obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia, and treatment of chronic pain. However, blockade is less intense than spinal anaesthesia, with greater chance of missed segments, and the dose of drug injected is potentially dangerous if incorrectly placed.

Opioid analgesic drugs may be injected into the epidural space to provide analgesia.

(For anatomy, path taken by needle, etc., see Epidural space.)

deep and superficial infiltration with local anaesthetic is performed.

deep and superficial infiltration with local anaesthetic is performed.

16–19 G Tuohy needles are usually employed, especially for catheter insertion. The curved blunt tip reduces the risk of dural puncture and facilitates catheter direction (Fig. 63). The needle is usually marked at 1 cm intervals (Lee markings), and may be winged. The Crawford needle (straight-tipped with an oblique bevel) is sometimes used. The stylet is removed when the needle tip is gripped by the interspinous ligament (see Vertebral ligaments). Less damage to the longitudinal ligamentous fibres has been claimed if the needle is inserted with the bevel facing laterally; the needle may then be rotated 90° once the space is entered. However, insertion with the bevel facing cranially is usually advocated, since this avoids the risk of dural puncture during rotation of the needle.

16–19 G Tuohy needles are usually employed, especially for catheter insertion. The curved blunt tip reduces the risk of dural puncture and facilitates catheter direction (Fig. 63). The needle is usually marked at 1 cm intervals (Lee markings), and may be winged. The Crawford needle (straight-tipped with an oblique bevel) is sometimes used. The stylet is removed when the needle tip is gripped by the interspinous ligament (see Vertebral ligaments). Less damage to the longitudinal ligamentous fibres has been claimed if the needle is inserted with the bevel facing laterally; the needle may then be rotated 90° once the space is entered. However, insertion with the bevel facing cranially is usually advocated, since this avoids the risk of dural puncture during rotation of the needle.

the epidural space is identified by exploiting the negative pressure that is usually present within it. Methods include: the hanging drop technique; a bubble indicator placed at the needle hub; collapsing drums or balloons (e.g. Macintosh’s); and the ‘loss of resistance’ technique:

the epidural space is identified by exploiting the negative pressure that is usually present within it. Methods include: the hanging drop technique; a bubble indicator placed at the needle hub; collapsing drums or balloons (e.g. Macintosh’s); and the ‘loss of resistance’ technique:

– saline: minimal ‘give’ when compressed, thus easier to judge resistance to injection. May be confused with CSF if dural puncture occurs (differentiated by detection of glucose/protein in CSF but not in saline, using reagent strips).

– air: avoids confusion with CSF but compressible in the syringe, i.e. ‘bounces’; judgement of loss of resistance is therefore harder. Neckache is common and thought to be caused by small air emboli (may be detected by sensitive Doppler ultrasound). Pneumocephalus has been reported.

– local anaesthetic: may be less painful during insertion, but risks iv or subarachnoid injection.

injection of a test dose through the needle is controversial and rarely performed, especially if a catheter is to be inserted.

injection of a test dose through the needle is controversial and rarely performed, especially if a catheter is to be inserted.

– single or fractionated injections are controversial, as above.

– assessment and management of blockade: as for spinal anaesthesia.

a catheter technique is almost always used.

a catheter technique is almost always used.

bupivacaine, levobupivacaine or ropivacaine 0.25–0.75%, and lidocaine 1–2%, are most commonly used in the UK. Onset with bupivacaine is about 15–30 min; effects last about 1.5–2.5 h. Lower concentrations of bupivacaine (≤ 0.1%), especially combined with opioids, e.g. fentanyl 2–4 µg/ml, are commonly used to provide analgesia whilst allowing mobility, particularly in obstetrics and for postoperative analgesia (see Spinal opioids). Infusions (≤ 15–20 ml/h) or boluses (≤ 20 ml) may be used; the former are especially common postoperatively since the duration of action is shorter than with concentrated solutions. Onset with lidocaine is about 5–15 min; effects last about 1–1.5 h if 1: 200 000 adrenaline is added. Higher concentrations are used if muscle relaxation is required. Alkalinised solutions produce faster onset of denser blockade.

bupivacaine, levobupivacaine or ropivacaine 0.25–0.75%, and lidocaine 1–2%, are most commonly used in the UK. Onset with bupivacaine is about 15–30 min; effects last about 1.5–2.5 h. Lower concentrations of bupivacaine (≤ 0.1%), especially combined with opioids, e.g. fentanyl 2–4 µg/ml, are commonly used to provide analgesia whilst allowing mobility, particularly in obstetrics and for postoperative analgesia (see Spinal opioids). Infusions (≤ 15–20 ml/h) or boluses (≤ 20 ml) may be used; the former are especially common postoperatively since the duration of action is shorter than with concentrated solutions. Onset with lidocaine is about 5–15 min; effects last about 1–1.5 h if 1: 200 000 adrenaline is added. Higher concentrations are used if muscle relaxation is required. Alkalinised solutions produce faster onset of denser blockade.

lumbar blockade: 10–30 ml is usually adequate. Rough guide: 1.5 ml/segment to be blocked, including sacral segments; 1.0 ml/segment if over 50 years or in pregnancy; 0.75 ml/segment if over 80 years.

lumbar blockade: 10–30 ml is usually adequate. Rough guide: 1.5 ml/segment to be blocked, including sacral segments; 1.0 ml/segment if over 50 years or in pregnancy; 0.75 ml/segment if over 80 years.

Effect of gravity: the dependent side tends to experience faster and denser block.

thoracic block: 3–5 ml is used to block 2–4 segments at the required level.

thoracic block: 3–5 ml is used to block 2–4 segments at the required level.

cervical block: 6–8 ml is usually used.

cervical block: 6–8 ml is usually used.

tachyphylaxis is common; it may be related to local pH changes but the precise mechanism is unclear.

tachyphylaxis is common; it may be related to local pH changes but the precise mechanism is unclear.

• Effects: similar to spinal anaesthesia, but block (and hypotension) are slower in onset. Density of block and muscle relaxation are less, with greater incidence of incomplete block. Motor block may be assessed using the Bromage scale.

• Contraindications: as for spinal anaesthesia.

related to insertion of needle/catheter:

related to insertion of needle/catheter:

– trauma:

– dural tap: usually obvious if caused by the epidural needle, as CSF flows back. Puncture by the epidural catheter may be harder to detect; flow of CSF may not be obvious, especially if saline was used to identify the epidural space.

– knotting of the catheter is possible if excessive lengths are inserted.

– hypotension as for spinal anaesthesia.

– local anaesthetic toxicity due to systemic absorption or iv injection.

– accidental spinal blockade (subarachnoid): onset is usually within a few minutes. May lead to total spinal block if a large amount of drug is injected, with rapidly ascending motor and sensory blockade, respiratory paralysis and central apnoea, cranial nerve involvement with fixed dilated pupils and loss of consciousness. Management includes oxygenation with tracheal intubation and IPPV, and cardiovascular support. Recovery without adverse effects is usual if hypoxaemia and hypotension are avoided.

– isolated cranial nerve palsies, e.g. fifth and sixth, and Horner’s syndrome, have been reported.

Extensive blocks may develop after top-up injections during apparently normal epidural blocks.

– prolonged blockade: uncommon; has lasted up to 8–12 h after the last injection.

– anterior spinal artery syndrome: thought to be related to severe hypotension, not to the technique itself.

– adverse drug reactions to agents used: rare.

– arachnoiditis, cauda equina syndrome.

– abscess formation/meningitis: thought to be rare if aseptic techniques are used.

Epidural opioids, see Spinal opioids

Epidural space. Continuous space within the vertebral column, extending from the foramen magnum to the sacrococcygeal membrane of the sacral canal. The vertebral canal becomes triangular in cross-section in the lumbar region, its base anterior; the epidural space is that part external to the spinal dura. It is very narrow anteriorly, and up to 5 mm wide posteriorly.

internal: dura mater of the spinal cord (at the foramen magnum, reflected back as the periosteal lining of the vertebral canal).

internal: dura mater of the spinal cord (at the foramen magnum, reflected back as the periosteal lining of the vertebral canal).

– posteriorly: ligamenta flava, and periosteum lining the vertebral laminae.

Contains epidural fat, epidural veins (Batson’s plexus), lymphatics and spinal nerve roots. Connective tissue layers have been demonstrated by radiology and endoscopy within the epidural space, in some cases (rarely) dividing it into right and left portions.

artefactual or transient negative pressure:

artefactual or transient negative pressure:

– anterior dimpling of the dura by the needle.

– back flexion causing stretching of the dural sac, and/or squeezing out of CSF.

– transmitted negative intrapleural pressure via thoracic paravertebral spaces.

– relative overgrowth of the vertebral canal compared with the dural sac.

– true positive pressure: bulging of dura due to pressure of CSF.

• Passage taken by an epidural needle when entering the epidural space (median approach):

3: supraspinous ligament (along the tips of spinous processes from C7 to sacrum).

3: supraspinous ligament (along the tips of spinous processes from C7 to sacrum).

4: interspinous ligament (between spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae).

4: interspinous ligament (between spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae).

5: ligamentum flavum (between laminae of adjacent vertebrae).

5: ligamentum flavum (between laminae of adjacent vertebrae).

The normal distance between the skin and the epidural space varies between 2 and 9 cm.

For the lateral approach: 1, 2, 5, 6.

See also, Epidural anaesthesia; Vertebrae; Vertebral ligaments

Epidural volume expansion, see Combined spinal–epidural anaesthesia

Epiglottitis. Infective inflammation of the epiglottis, often resulting in upper airway obstruction. Caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in over 50% of cases. Most common in children aged 2–5 years but may also occur in adults (usually aged 20–40 years); the incidence in the UK has fallen since a specific vaccine was introduced. Classically follows an acute course, with fever, marked systemic upset, stridor and adoption of the sitting position with the jaw thrust forward and an open drooling mouth. These features, plus absence of cough, help distinguish it from croup. Epiglottitis may progress to complete airway obstruction, which may be provoked by pharyngeal examination and anxiety (e.g. due to iv cannulation). Although lateral X-rays of the neck may reveal epiglottic enlargement, they may also provoke obstruction, and clinical assessment is sufficient in severe cases. Pulmonary oedema may occur if obstruction is severe.

– general state: exhaustion, toxaemia, etc.

– respiratory distress: stridor, use of accessory respiratory muscles, including flaring of the nostrils, intercostal and suprasternal recession, tachypnoea, cyanosis.

experienced anaesthetic, paediatric and ENT help should be sought.

experienced anaesthetic, paediatric and ENT help should be sought.

nebulised adrenaline (0.4 ml/kg [400 µg/kg] of a 1 : 1000 racemic solution to a maximum of 5 ml [5 mg]).

nebulised adrenaline (0.4 ml/kg [400 µg/kg] of a 1 : 1000 racemic solution to a maximum of 5 ml [5 mg]).

iv fluids and antibacterial drugs are required, although iv cannulation should not be attempted before relief of the airway obstruction. Third-generation cephalosporins are the drugs of choice because of increasing resistance to the traditionally used chloramphenicol or ampicillin.

iv fluids and antibacterial drugs are required, although iv cannulation should not be attempted before relief of the airway obstruction. Third-generation cephalosporins are the drugs of choice because of increasing resistance to the traditionally used chloramphenicol or ampicillin.

anaesthesia is as for airway obstruction; commonly inhalational induction using sevoflurane in O2 with the patient sitting until tracheal intubation is possible. Induction is usually slow. Apparatus for difficult intubation plus facilities for urgent tracheostomy must be available. Atropine may be given once an iv cannula is sited. An oral tracheal tube is passed initially, and is changed for a nasal tube to allow better fixation and comfort.

anaesthesia is as for airway obstruction; commonly inhalational induction using sevoflurane in O2 with the patient sitting until tracheal intubation is possible. Induction is usually slow. Apparatus for difficult intubation plus facilities for urgent tracheostomy must be available. Atropine may be given once an iv cannula is sited. An oral tracheal tube is passed initially, and is changed for a nasal tube to allow better fixation and comfort.

intubation is usually required for less than 24 h. Spontaneous ventilation is usually acceptable. Humidification is essential. Sedation may not be required, but care must be taken to avoid accidental extubation.

intubation is usually required for less than 24 h. Spontaneous ventilation is usually acceptable. Humidification is essential. Sedation may not be required, but care must be taken to avoid accidental extubation.

members of the patient’s household should receive prophylactic antibacterial agents.

members of the patient’s household should receive prophylactic antibacterial agents.

• Traditionally classified into:

– grand mal (tonic–clonic convulsions): tonic (sustained muscle contraction) followed by clonic (jerking) phases lasting about 30 s each, with loss of consciousness. May be preceded by prodromal symptoms hours or days before, and an aura minutes before.

– other types of generalised seizures include atonic and myoclonic.

– may occur with (complex partial) or without (simple partial) derangement of consciousness.

Definition of disease is difficult because certain stimuli will induce convulsions in normal subjects, e.g. hypoxia, hypo/hyperglycaemia. Usually idiopathic, especially in childhood; intracranial lesions and infections (e.g. encephalitis) must be excluded in adults presenting with a single seizure. Pyrexia is a common cause in children; other causes are as for convulsions.

Treatment is with anticonvulsant drugs, and is directed at any underlying cause.

preoperative assessment: frequency of seizures, date of last seizure, drug therapy (including measurement of blood levels where appropriate). Identification of cause if known.