Dyspnea

Perspective

Dyspnea is the term applied to the sensation of breathlessness and the patient’s reaction to that sensation. It is an uncomfortable awareness of breathing difficulties that in the extreme manifests as “air hunger.” Dyspnea is often ill defined by patients, who may describe the feeling as shortness of breath, chest tightness, or difficulty breathing. Dyspnea results from a variety of conditions, ranging from nonurgent to life-threatening. Neither the clinical severity nor the patient’s perception correlates well with the seriousness of underlying pathology and may be affected by emotions, behavioral and cultural influences, and external stimuli.1,2

The following terms may be used in the assessment of the dyspneic patient:

Tachypnea: A respiratory rate greater than normal. Normal rates range from 44 cycles/min in a newborn to 14 to 18 cycles/min in adults.

Hyperpnea: Greater than normal minute ventilation to meet metabolic requirements.

Hyperventilation: A minute ventilation (determined by respiratory rate and tidal volume) that exceeds metabolic demand. Arterial blood gases (ABGs) characteristically show a normal partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) with an uncompensated respiratory alkalosis (low partial pressure of carbon dioxide [PCO2] and elevated pH).

Dyspnea on exertion: Dyspnea provoked by physical effort or exertion. It often is quantified in simple terms, such as the number of stairs or number of blocks a patient can manage before the onset of dyspnea.

Orthopnea: Dyspnea in a recumbent position. It usually is measured in number of pillows the patient uses to lie in bed (e.g., two-pillow orthopnea).

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea: Sudden onset of dyspnea occurring while reclining at night, usually related to the presence of congestive heart failure.

Pathophysiology

The actual mechanisms responsible for dyspnea are unknown. Normal breathing is controlled both centrally by the respiratory control center in the medulla oblongata and peripherally by chemoreceptors located near the carotid bodies, and mechanoreceptors in the diaphragm and skeletal muscles.3 Any imbalance among these sites is perceived as dyspnea. This imbalance generally results from ventilatory demand being greater than capacity.4

Diagnostic Approach

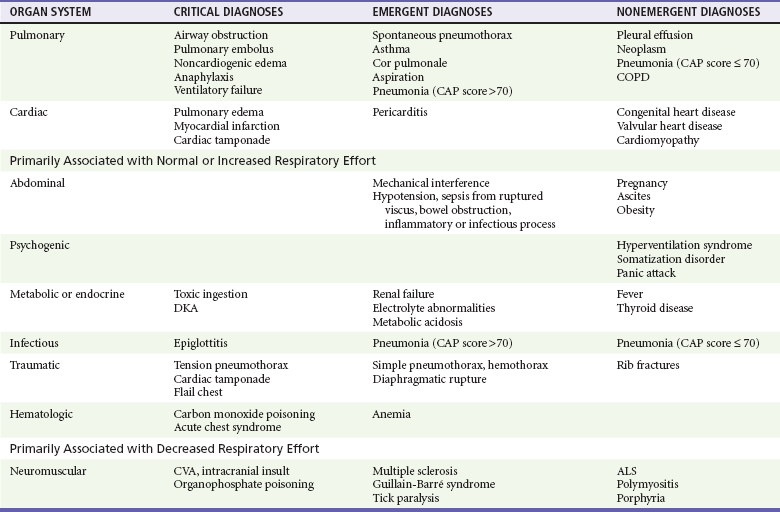

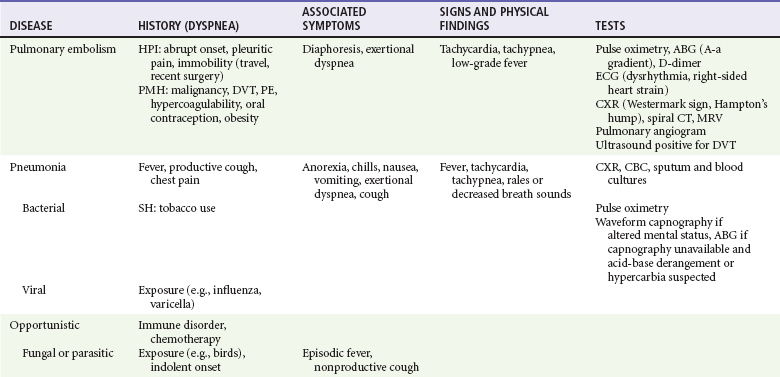

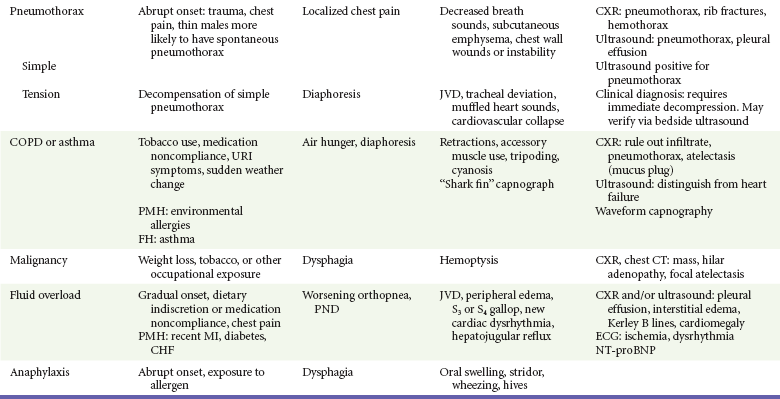

Dyspnea is subjective and has many different potential causes. The differential diagnosis can be divided into acute and chronic causes, of which many are pulmonary. Other causes include cardiac, metabolic, infectious, neuromuscular, traumatic, and hematologic conditions (Table 25-1).

Pivotal Findings

Duration of Dyspnea.: Chronic or progressive dyspnea usually denotes primary cardiac or pulmonary disease.5 Acute dyspneic spells may result from asthma exacerbation; infection; pulmonary embolus; intermittent cardiac dysfunction; psychogenic causes; or inhalation of irritants, allergens, or foreign bodies.

Onset of Dyspnea.: Sudden onset of dyspnea should lead to consideration of pulmonary embolism (PE) or spontaneous pneumothorax. Dyspnea that builds slowly over hours or days may represent a flare of asthma or COPD; pneumonia; recurrent, small pulmonary emboli; congestive heart failure; or malignancy.

Positional Changes.: Orthopnea can result from left-sided heart failure, COPD, or neuromuscular disorders. One of the earliest symptoms seen in patients with diaphragmatic weakness from neuromuscular disease is orthopnea.6 Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is most common in patients with left-sided heart failure5 but also occurs in COPD. Exertional dyspnea commonly is associated with COPD but also can be seen with poor cardiac reserve and abdominal loading. Abdominal loading, caused by ascites, obesity, or pregnancy, leads to elevation of the diaphragm, resulting in less effective ventilation and dyspnea.

Symptoms

Patient descriptions of dyspnea vary significantly and generally correlate poorly with severity. Fever suggests an infectious cause. Anxiety or overwhelming fear, particularly if it precedes the onset of dyspnea, may point to panic attack or psychogenic dyspnea, if no organic cause can be isolated. PE or myocardial infarction may cause isolated dyspnea with or without associated chest pain, particularly if the pain is constant, dull, or visceral.7 If the pain is sharp and worsened by deep breathing but not by movement, pleural effusion, pleurisy, or pleural irritation from pneumonia or PE are possible. Spontaneous pneumothorax also may produce sharp pain with deep breathing that is not worsened by movement.

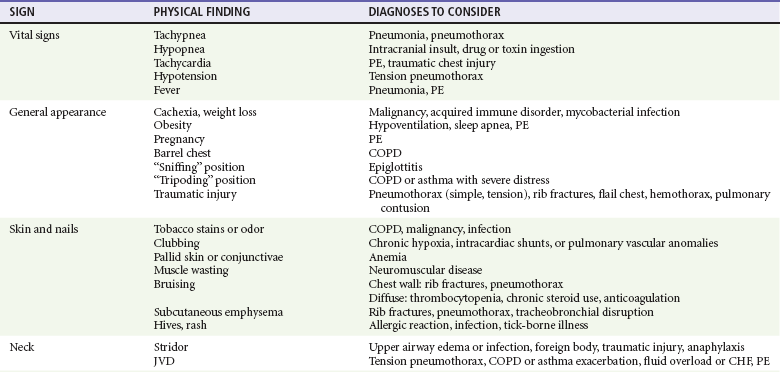

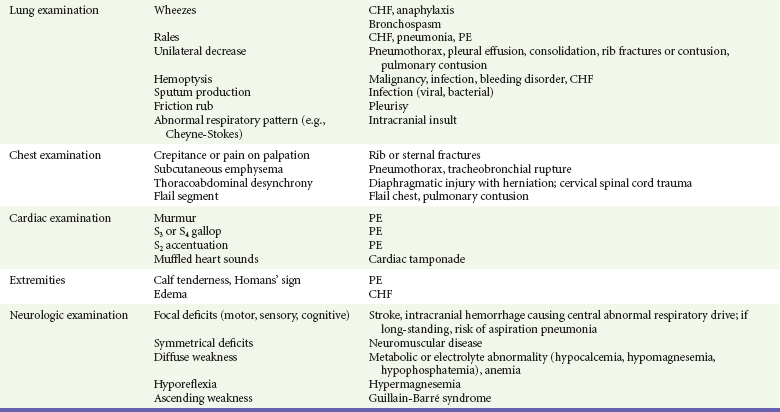

Signs

Physical signs in dyspneic patients may be consistent with specific illnesses (Table 25-2). Physical findings found in specific diseases also can be grouped as presenting patterns (Table 25-3).

Ancillary Studies

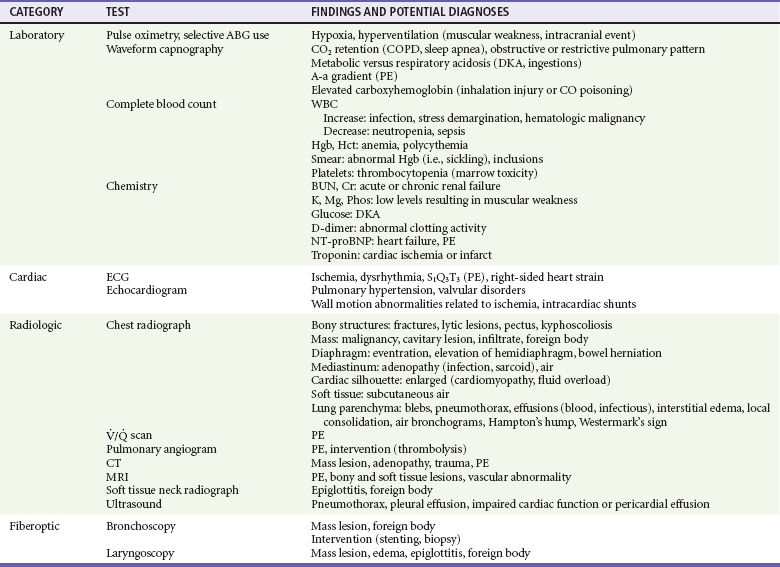

Specific findings obtained from the history and physical examination should be used to determine which ancillary studies are needed (Table 25-4). Bedside oxygen saturation determinations, or selective use of ABGs when oximetry is not reliable, are useful in determining the degree of hypoxia and the need for supplemental oxygen or assisted ventilation. An additional resource for quickly assessing ventilatory status is noninvasive waveform capnography. End-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) values correlate well with arterial carbon dioxide (CO2), and together with the shape of the capnogram can be helpful in assessing the adequacy of ventilations as well as underlying causes of the dyspnea (see Chapter 5).8 An electrocardiogram may be useful if history or physical examination findings suggest heart failure, ischemic cardiac disease, dysrhythmia, or pulmonary hypertension. Bedside ultrasound is useful to rapidly diagnose pulmonary edema, pneumothorax, and COPD, as well as deep venous thrombosis.9,10

Expanded availability of specific blood biomarkers relevant to emergent evaluation of dyspnea provides improved immediate decision support and allows for short- and long-term prognostication.11–14 These include cardiac markers and D-dimer assay, which are useful in pursuing causes such as cardiac ischemia or venous thromboembolic disease. Amino-terminal pro-B–type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) analysis adds both diagnostic and prognostic value for several causes of dyspnea, including heart failure, PE, and ischemic cardiac disease.13–16

If venous thromboembolism is suspected, D-dimer testing, with or without chest computed tomographic angiography, duplex venous ultrasonography, or, rarely, ventilation-perfusion scanning, is performed.17 If dyspnea is believed to be upper airway in origin, direct or fiberoptic laryngoscopy or a soft tissue lateral radiograph of the neck may be useful.

Differential Diagnosis

The range and diversity of pathophysiologic conditions that produce dyspnea render a simple algorithmic approach difficult. The primary branch point is the determination of whether the dyspnea primarily is cardiopulmonary or toxic-metabolic in origin. After initial stabilization and assessment, findings from the history, physical examination, and ancillary testing are collated to match patterns of disease that produce dyspnea. This process is updated periodically as new information becomes available. Table 25-3 presents recognizable patterns of disease for common dyspnea-producing conditions, along with specific associated symptoms.

Critical Diagnoses

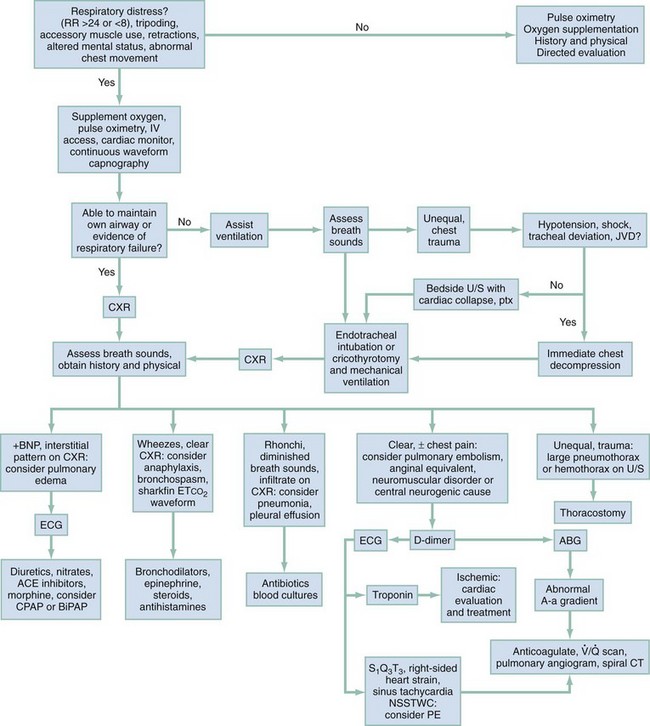

Several critical diagnoses should be promptly considered to determine the best treatment options to stabilize the patient. Tension pneumothorax is such a critical diagnosis and is diagnosed by history and physical examination. If a dyspneic patient has diminished breath sounds on one side, ipsilateral hyper-resonance, severe respiratory distress, hypotension, and oxygen desaturation, prompt decompression of presumptive tension pneumothorax is indicated. Bedside ultrasonography can confirm pneumothorax in less obvious cases. If dyspnea and stridor indicate upper airway obstruction, early, definitive assessment and intervention occur in the ED or operating room. Complete obstruction by a foreign body warrants the Heimlich maneuver until the obstruction is relieved or the patient is unconscious, followed rapidly by direct laryngoscopy for foreign body removal. Heart failure and pulmonary edema can produce dyspnea and respiratory failure and require prompt intervention if severe.18 Significant dyspnea and wheezing in anaphylaxis require immediate use of parenteral epinephrine in addition to supportive measures. Severe bronchospastic exacerbations of asthma at any age may lead rapidly to respiratory failure and arrest and should receive vigorous attention, including continuous or frequent administration of a beta-agonist aerosol and steroid therapy.19 Ultrasound may also be of benefit in rapidly distinguishing between COPD and heart failure.10,20 As mentioned earlier, waveform capnography is a valuable adjunct for assessing the severity and determining the cause of respiratory distress.

Emergent Diagnoses

Asthma and COPD exacerbations can result in marked dyspnea with bronchospasm and decreased ventilatory volumes.21 Sudden onset of dyspnea with a decreased oxygen saturation on room air accompanied by sharp chest pain may represent PE. Dyspnea accompanied by decreased breath sounds and tympany on percussion on one side is seen with spontaneous pneumothorax. Dyspnea associated with decreased respiratory effort may represent a neuromuscular process, such as multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or myasthenia gravis. Unilateral rales, cough, fever, and dyspnea usually indicate pneumonia.

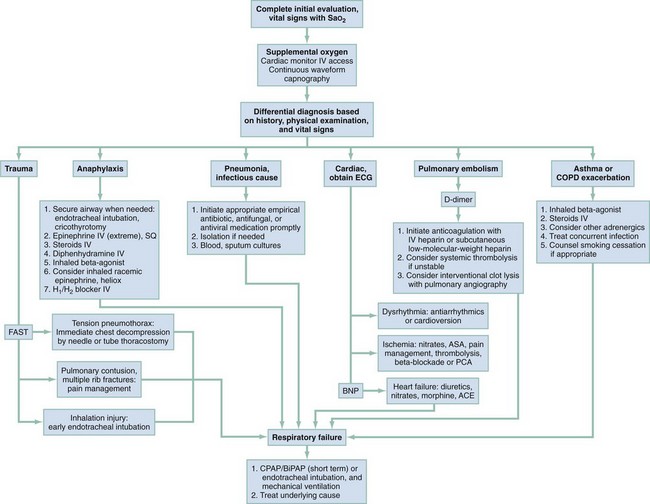

Figure 25-1 provides an algorithm for assessment and stabilization of a dyspneic patient. The initial division is based on the degree of breathing effort associated with the symptoms. The most critical diagnoses are considered first, and appropriate intervention undertaken.

All patients experiencing dyspnea, regardless of possible cause, should be promptly evaluated in the treatment area. Bedside pulse oximetry readings should be obtained, and the patient should be placed on a cardiac monitor. If the pulse oximetry result is less than 95% on room air, the patient should be placed on supplemental oxygen either by nasal cannula or mask, depending on the degree of desaturation detected. If necessary, breathing should be assisted with manual or mechanical ventilation, either noninvasively for the short term, or with the patient tracheally intubated for airway protection or prolonged ventilation.22

Empirical Management and Disposition

The management algorithm for dyspnea (Fig. 25-2) outlines the approach to treatment for most identifiable diseases. Unstable patients or patients with critical diagnoses must be stabilized and may require admission to an intensive care unit. Emergent patients who have improved with ED management may be admitted to an intermediate care unit. Patients diagnosed with urgent conditions in danger of deterioration without proper treatment or patients with severe comorbidities, such as diabetes, immunosuppression, or cancer, may also require admission for observation and treatment.

References

1. Hravnak, M, et al. Symptom expression in coronary heart disease and revascularization recommendations for black and white patients. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1701.

2. Coli, C, et al. Is there a link between the qualitative descriptors and the quantitative perception of dyspnea in asthma? Chest. 2006;130:436.

3. Dyspnea. Mechanisms, assessment, and management: A consensus statement. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:321.

4. Ofir, D, Laveneziana, P, Webb, KA, Lam, YM, O’Donnell, DE. Mechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:622.

5. Ailani, RK, et al. Dyspnea differentiation index: A new method for rapid separation of cardiac versus pulmonary dyspnea. Chest. 1999;119:1100.

6. Katz, SL, et al. Nocturnal hypoventilation: Predictors and outcomes in childhood progressive neuromuscular disease. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:998.

7. Lobo, JL, et al. Clinical syndromes and clinical outcome in patients with pulmonary embolism: Findings from the RIETE registry. Chest. 2006;130:1817.

8. Cinar, O, et al. Can mainstream end-tidal carbon dioxide measurement accurately predict the arterial carbon dioxide level of patients with acute dyspnea in ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:358–361.

9. Zanobetti, M, Poggioni, C, Pini, R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED? Chest. 2010;139:1140.

10. Zechner, PM, Aichinger, G, Rigaud, M, Wildner, G, Prause, G. Prehospital lung ultrasound in the distinction between pulmonary edema and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:389.

11. Januzzi, JL, Jr., Rehman, S, Mueller, T, van Kimmenade, RR, Lloyd-Jones, DM. Importance of biomarkers for long-term mortality prediction in acutely dyspneic patients. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1814.

12. Gori, CS, Magrini, L, Travaglino, F, Di Somma, S. Role of biomarkers in patients with dyspnea. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:229.

13. Baggish, AL, et al. A validated clinical and biochemical score for the diagnosis of acute heart failure: The ProBNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) acute heart failure score. Am Heart J. 2006;151:48.

14. Lam, LL, et al. Meta-analysis: Effect of B-type natriuretic peptide testing on clinical outcomes in patients with acute dyspnea in the emergency setting. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:728.

15. de Lemos, JA, Morrow, DA. Combining natriuretic peptides and necrosis markers in the assessment of acute coronary syndromes. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4:S37.

16. Melanson, SE, et al. Combination of D-dimer and amino-terminal pro-B–type natriuretic peptide testing for the evaluation of dyspneic patients with and without acute pulmonary embolism. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1326.

17. Kline, JA, Wells, PS. Methodology for a rapid protocol to rule out pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:266.

18. Murray, S. Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) and acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema (ACPO) in the emergency department. Aust Crit Care. 2002;15:51.

19. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdIn.pdf.

20. Cibinel, GA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reproducibility of pleural and lung ultrasound in discriminating cardiogenic causes of acute dyspnea in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:65–70.

21. O’Donnell, DE, Guenette, JA, Maltais, F, Webb, KA. Decline of resting inspiratory capacity in COPD: Impact on breathing pattern, dyspnea and inspiratory capacity during exercise. Chest. 2012;141:753–762.

22. Schmidbauer, W, et al. Early prehospital use of non-invasive ventilation improves acute respiratory failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:626–627.

, ventilation-perfusion; WBC, white blood cell.

, ventilation-perfusion; WBC, white blood cell.

ventilation-perfusion ratio; U/S, ultrasound.

ventilation-perfusion ratio; U/S, ultrasound.