Problem 12 Dysphagia and weight loss in a middle-aged man

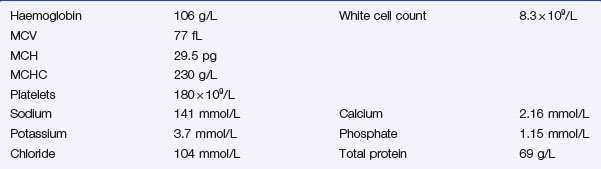

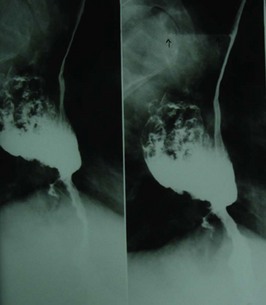

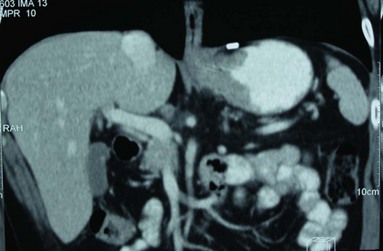

A further investigation is performed and a representative film is shown (Figure 12.1).

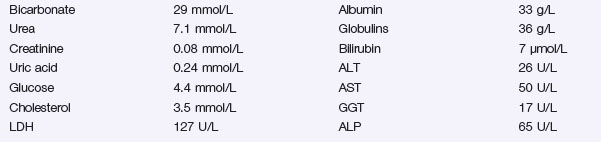

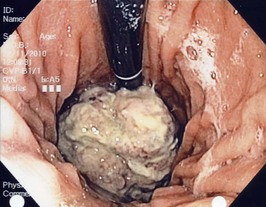

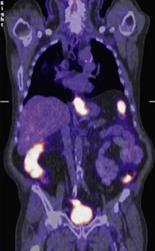

Based on the radiological findings, the patient is referred for another investigation (Figure 12.2).

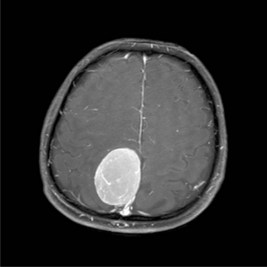

The lesion is biopsied and confirmed to be a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient is referred for further staging investigations (Figure 12.3 and Figure 12.4.).

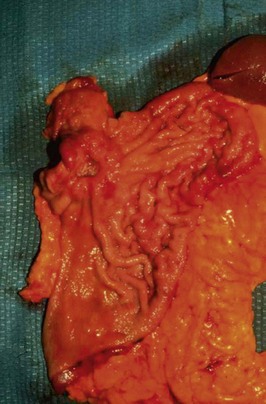

Following three cycles of chemotherapy (over 3 months) and 4 weeks of stabilization, the patient underwent surgery. Figure 12.5 shows the operative view of the upper abdomen.

Answers

Other diagnoses to consider include:

A.2 Investigations should include:

The patient therefore has a Type III tumour.

A.8 The treatment of gastric cancer depends on:

Issues to Consider

, www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/stomach. A web page from the National Cancer Institute with links providing current information on many different aspects of gastric cancer (in the form of a web-based information booklet)

, www.surgical-tutor.org.uk. A surgical resource with extensive up-to-date information on gastric cancer

, www.helico.com. The website of the Helicobacter Foundation, founded by Dr Barry Marshall