Chapter 2 DYSPHAGIA AND ODYNOPHAGIA

DYSPHAGIA

Taking the dysphagia history

A good history will elucidate the site and the general pathophysiological process in 80% of cases, and is vital before embarking on a focussed and cost effective utilisation of specific diagnostic techniques. Frequently, patients will describe food sticking or holding up either retrosternally or in the neck. However, more atypical symptoms can include regurgitation, a sense of fullness retrosternally and hiccup. Dysphagia is distinguished from odynophagia (pain on swallowing) by the perception of actual bolus hold up. The aims of the history are to:

Where does the food stick?

Retrosternal hold-up suggests that the disorder lies within the oesophagus. If the site of hold-up is in the neck, the pathology can lie either in the oesophagus or in the pharynx (Figure 2.1). Due to referred sensation, the site of perceived hold-up is above the suprasternal notch in 30% of cases where the actual hold-up is within the oesophageal body. Therefore, the next batch of questions aims to distinguish pharyngeal from oesophageal dysfunction.

Is one or more of the four cardinal symptoms of pharyngeal dysfunction present?

The four cardinal symptoms of pharyngeal dysfunction are:

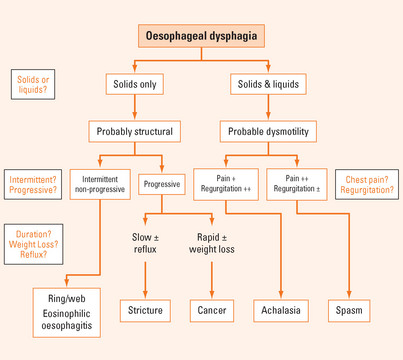

If oesophageal dysphagia is suspected, the next step is to establish whether it is a structural or motor disorder (Tables 2.1 and 2.2).

TABLE 2.1 Structural oesophageal disorders causing dysphagia

TABLE 2.2 Aetiology of pharyngeal dysphagia*

| Structural | Neuromyogenic |

How long has dysphagia been present; is it intermittent, is it progressive?

Longstanding dysphagia is compatible with a benign condition. Slowly progressive, longstanding dysphagia, particularly if reflux is or has been experienced, is highly suggestive of a peptic stricture. A short history of dysphagia particularly with rapid progression (weeks or months) and associated weight loss is highly suggestive of oesophageal cancer. Longstanding, intermittent, non-progressive dysphagia purely for solids is indicative of a fixed structural lesion such as a distal oesophageal ring or proximal oesophageal mucosal web.

Does the patient regurgitate?

While regurgitation can be associated with solid bolus hold-up during a meal, spontaneous regurgitation between meals (generally fluid and ‘frothy’ saliva) is highly suggestive of dysmotility (see below).

Does the patient experience chest pain or discomfort?

If oesophageal dysmotility is strongly suspected, distinction between achalasia and oesophageal spasm can be difficult at times. Achalasia is very much more common than spasm. In achalasia, chest pain is more prominent early in the disease, but over the years tends to diminish and may disappear as dysphagia and regurgitation worsen. In contrast, the chest pain of spasm is the predominant symptom and can be quite severe. Due to poor oesophageal clearance, regurgitation is frequently more impressive in achalasia than it is in the case of spasm. The oesophagus generally dilates over time in the context of achalasia, but this is less prevalent with spasm. Finally, there can be significant overlap between the two syndromes and spasm can evolve into more typical achalasia over time as they both share a similar underlying inhibitory neuropathic process. Oesophageal motility disorders can be classified as either primary (e.g. achalasia or diffuse oesophageal spasm) or secondary (e.g. scleroderma) (Table 2.3).

| Primary | Secondary |

Examination of the patient with dysphagia

In the context of oesophageal dysphagia, the physical examination is generally unremarkable. However one should examine the skin for features compatible with connective tissue disorders particularly scleroderma and CREST syndrome. Muscle weakness or wasting might be evident if myositis is present, and this can overlap with other connective tissue disorders affecting the oesophagus. Signs of malnutrition, weight loss and pulmonary complications from possible aspiration should be looked for. If pharyngeal dysphagia is suspected, careful evaluation for neuromuscular disorders is important (see below).

Diagnostic tests for oesophageal dysphagia

Endoscopy is virtually always indicated in the dysphagic patient. It is necessary to identify and biopsy ulcerative pathology, malignancy and infective oesophagitis. A normal endoscopy, however, does not rule out a structural abnormality. Consider taking mid-oesophageal biopsies to rule out eosinophilic oesophagitis (abnormal mucosal eosinophilia in the oesophagus on histology [>24 eosinophils/ high power field]) in the setting of any case of unexplained dysphagia or food impaction. The ringed oesophagus is not always apparent unless adequate distension or insufflation of the oesophagus is achievable. The so-called ‘multi-ringed’ oesophagus, characteristic of eosinophilic oesophagitis, may have very subtle features such as longitudinal furrows, the ‘feline’ oesophagus with typical corrugation compatible with longitudinal shortening as well as the development of mucosal rings. Reflux oesophagitis and ulcerative oesophagitis (e.g. herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus [CMV], Candida) have typical appearances. Strictures can be biopsied and dilated at the time of endoscopy. The finding of food, fluid or salivary residue within the oesophagus is highly suggestive of dysmotility, particularly achalasia.

Diagnostic approach in suspected oropharyngeal dysphagia

The aetiology of pharyngeal dysphagia can be considered in 2 broad categories; structural disorders or neuromyogenic causes (Table 2.2). The range of potential neuromyogenic causes of pharyngeal dysphagia is broad but the most common is stroke. At least 50% of stroke patients experience pharyngeal dysphagia. While considering the likely underlying cause in a patient, there are four fundamental issues to consider in the work-up of these patients as listed in Table 2.4.

Establish the aspiration risk

This is achieved by a video radiographic swallow study sometimes called the modified barium swallow (MBS). This is frequently conducted by the speech pathologist in conjunction with the radiologist. The MBS will determine the presence, the severity and the timing of aspiration. During the examination, the speech pathologist may modify the patient’s swallow technique, head posture and swallowed bolus consistency to determine whether the aspiration can be eliminated by such manoeuvres. This is important in tailoring patient management and deciding whether non-oral feeding (by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] or nasogastric [NG] tube) might be indicated.

PAIN ON SWALLOWING (ODYNOPHAGIA)

Odynophagia is the symptom of pain on swallowing, generally arising from irritation of an inflamed or ulcerated mucosa by the swallowed bolus during its passage through the pharynx or oesophagus. The aetiology is generally infective, inflammatory or corrosive (Table 2.5). Infective causes are most often encountered in the immunocompromised host. The symptom of odynophagia nearly always warrants endoscopic investigation.

| Infective |

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

In reflux disease, odynophagia almost always occurs in the context of oesophagitis. The patient typically describes a sensation of pain or discomfort coincident with passage of the bolus through the oesophagus, sometimes combined with a sense of transient bolus hold-up. The sense of bolus arrest can dominate the symptom complex if the oesophagitis has progressed to stricture formation, but is not infrequently perceived even in the absence of a stricture. The symptom of odynophagia always warrants endoscopic investigation. For a detailed account of investigation and management of reflux disease, refer to Chapter 3.

Oesophageal candidiasis

This infection usually occurs in patients receiving prolonged courses of antibiotics or who are immunosuppressed (e.g. as a result of human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] or chemotherapy) or who are using systemic or inhaled steroids. Conditions commonly associated with oesophageal candidiasis include diabetes, lymphoma and other malignancies particularly during chemotherapy when these patients are neutropenic. The oesophageal infection may be accompanied by oral or pharyngeal candidiasis, particularly in the context of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The endoscopic features are white plaques on an erythematous mucosa which can progress to necrosis and ulceration. Diagnosis is confirmed by brushings and biopsy demonstrating hyphae and tissue invasion by the organism. The features can be similar to those of infections due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) or CMV and biopsy is necessary to distinguish between these conditions. Therapy is aimed at treating the underlying disease or conditions that predispose to the infection. Specific antifungal therapy, such as nystatin or amphotericin lozenges, are useful for oropharyngeal but not oesophageal candidiasis. Oral fluconazole is recommended for oesophageal candidiasis. Unresponsive cases may benefit from an intravenous echinocandin (e.g. caspofungin).

Caustic oesophageal injury

This is frequently caused by ingestion of household substances including strong bleach, alkali or acid solutions. Interestingly, the severity of the corrosive injury doesn’t always correlate with the severity of the pain and odynophagia. Hypothetically there is an increased risk of perforation during endoscopy in these patients. However, if it is done early (within 48 hours) and the scope is not pushed passed points of circumferential ulceration, the procedure is safe and important as it establishes the extent and severity of damage. A chest X-ray is also important as it can detect pulmonary infiltrates due to aspiration and possible signs of perforation. Therapy includes IV fluids and airway management as appropriate. The use of steroids is controversial and there is no high-level evidence supporting its efficacy. If steroids are used, they should be used in partial thickness burns and with concurrent antibiotics. If oral feeding cannot be resumed early, enteral or parenteral feeding is considered.

Achem SR, Devault KR. Dysphagia in aging. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:357-371.

Castell D.O., Richter J., editors. The esophagus, 4th edn, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines: management of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(2):455-478.

Ferguson DD, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Eosinophilic esophagitis: an update. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:2-8.

Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, et al. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut. 2007;56:615-620.