Chapter 4 DYSPEPSIA AND FUNCTIONAL DYSPEPSIA

DEFINITIONS

The Rome III committee has redefined functional dyspepsia and limited the term to refer to the four following symptoms: bothersome post-prandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, or epigastric burning. The remaining symptoms of discomfort listed above have been allocated clinical entities of their own, and together they comprise the functional gastroduodenal disorders (Table 4.1). In addition, as shown in Table 4.2, there are two new diagnostic categories within functional dyspepsia; namely postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS).

TABLE 4.2 Subtypes of functional dyspepsia

| Diagnostic criteria*for postprandial distress syndrome |

| Must include one or both of the following: |

| Supportive criteria |

| Diagnostic criteria*for epigastric pain syndrome |

| Must include all of the following: |

| Supportive criteria |

* Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis

CAUSES

Organic

Organic causes of dyspepsia are many and varied as outlined in Table 4.3, but the majority of cases are due to peptic ulcer disease, gastro-oesophageal reflux and malignancy.

| Luminal |

Adapted from Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. 7th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

Functional gastroduodenal disorders

Functional gastroduodenal disorders account for around 60% of presentations but are a diagnosis of exclusion. Current criteria require the presence of symptoms during the last 3 months occurring at least several times per week, with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis and no evidence of structural disease on endoscopy (Tables 4.1 and 4.2).

The underlying pathophysiology of functional gastroduodenal disorders is incompletely understood. Gastric motility is abnormal in around 60% of cases with observed changes including delayed (or less often accelerated) gastric emptying, impaired proximal stomach accommodation leading to antral distension, and variable myoelectrical activity. None of these changes convincingly correlate with symptoms. Use of a gastric barostat balloon has demonstrated visceral hypersensitivity in over 40% of patients with dyspepsia.

MANAGEMENT

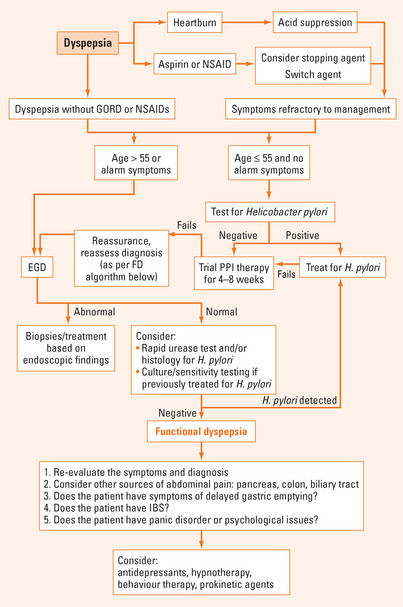

Figure 4.1 shows an algorithm for the approach to the patient with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Taking a thorough history with appropriate physical examination to clarify whether the symptoms are pancreatic, biliary or colonic in origin is an essential first step. Once a specific diagnosis has been made, treatment should be directed towards the specific condition. If uncomplicated dyspepsia is a consideration, discontinuing use of aspirin/NSAIDs and, if present, treatment of symptoms of GORD with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) should be instituted. It is critical to make an assessment of the presence of alarm symptoms and signs. Older age and/or presence of alarm features indicates the need for early endoscopy, whereas the remainder may be managed with a ‘test and treat’ strategy (referring to establishing the presence/absence of H. pylori).

Non-invasive testing for H. pylori utilising either a urea breath test or a stool antigen immunoassay is appropriate in most patients. Serology is less accurate and is generally not recommended unless there is no alternative. Those who are already undergoing endoscopy should have a biopsy routinely obtained based on current guidelines. In these patients, rapid urease testing (e.g. CLOtest) with or without histology is usually performed.

Response to therapy may be assessed most effectively with a urea breath test performed at least 4 weeks after completing antibiotic therapy, and at least one week after stopping PPI therapy. Treatment failures are most commonly treated with a second-line regimen of quadruple therapy utilising bismuth, a PPI and alternative antibiotics such as metronidazole and tetracycline for a further 2 weeks. Rescue therapy for subsequent treatment failures involves changing the antibiotics to levofloxacin or rifabutin along with a PPI. If symptoms persist despite eradication of H. pylori, a trial of PPI should be undertaken. Alternative diagnoses should be considered if there is a continued lack of response and consideration also given to gastric emptying studies and psychological assessment (Figure 4.1).

PPIs and H2-receptor antagonists are superior to placebo in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide or domperidone, also appear to be modestly effective. Domperidone has the advantage of limited crossing of the blood–brain barrier and, consequently, exhibits fewer centrally-mediated side effects compared with metoclopramide.

SUMMARY

H. pylori causes gastritis, peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma. A minority of patients with functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection will respond to anti-H. pylori therapy. False negative test results for H. pylori can occur in the setting of recent acid suppression. Ideally, patients should be off acid suppression therapy for 1–2 weeks prior to testing to avoid false-negative results. If standard triple therapy with a PPI, amoxicillin and clarithromycin fails to eradicate the infection, then the usual next management approach is to use quadruple therapy combining a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole and tetracycline for 2 weeks.

Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al. Initial poor quality of life and new onset of dyspepsia: results from a longitudinal follow-up study. Gut. 2007;56:321-327.

Gisbert JP. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:848-863.

Tack J, Lee KJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S211-S216.

Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479.

Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780.