CHAPTER 13 Dyspepsia

DEFINITION

Dyspepsia is derived from the Greek words dys and pepse and literally means “difficult digestion.” In current medical terminology, dyspepsia refers to a heterogeneous group of symptoms located in the upper abdomen. Dyspepsia is often broadly defined as pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen1,2 and may include multiple and varying symptoms such as epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, early satiation (also called early satiety), anorexia, belching, nausea and vomiting, upper abdominal bloating, and even heartburn and regurgitation. Patients with dyspepsia commonly report several of these symptoms.3

Earlier definitions considered dyspepsia to consist of all upper abdominal and retrosternal sensations—in effect, all symptoms considered to be referable to the proximal gastrointestinal tract.4 The Rome I and II consensus committees both defined dyspepsia as pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen.1,2 Discomfort includes postprandial fullness, upper abdominal bloating, early satiation, epigastric burning, belching, nausea, and vomiting. Heartburn may occur as part of the symptom constellation, but the Rome II committee decided that when heartburn is the predominant symptom, the patient should be considered to have GERD and not dyspepsia.

The most recent consensus committee, Rome III, has defined dyspepsia as the presence of symptoms considered by the physician to originate from the gastroduodenal region (Table 13-1).5 Only four symptoms (bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning) are now considered to be specific for a gastroduodenal origin, although many other symptoms are acknowledged to coexist with dyspepsia.

| SYMPTOM | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| More Specific | |

| Postprandial fullness | An unpleasant sensation perceived as the prolonged persistence of food in the stomach |

| Early satiation | A feeling that the stomach is overfilled soon after starting to eat, out of proportion to the size of the meal being eaten, so that the meal cannot be finished. Previously, the term early satiety was used, but satiation is the correct term for the disappearance of the sensation of appetite during food ingestion. |

| Epigastric pain | Epigastric refers to the region between the umbilicus and lower end of the sternum, within the midclavicular lines. Pain refers to a subjective, unpleasant sensation; some patients may feel that tissue damage is occurring. Epigastric pain may or may not have a burning quality. Other symptoms may be extremely bothersome without being interpreted by the patient as pain. |

| Epigastric burning | Epigastric refers to the region between the umbilicus and lower end of the sternum, within the midclavicular lines. Burning refers to an unpleasant subjective sensation of heat. |

| Less Specific | |

| Bloating in the upper abdomen | An unpleasant sensation of tightness located in the epigastrium. Bloating should be distinguished from visible abdominal distention |

| Nausea | Queasiness or sick sensation; a feeling of the need to vomit |

| Vomiting | Forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents associated with contraction of the abdominal and chest wall muscles. Vomiting is usually preceded by and associated with retching, repetitive contractions of the abdominal wall without expulsion of gastric contents. |

| Belching | Venting of air from the stomach or the esophagus |

* According to the Rome III committee.

Adapted from Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006. p 422.

In patients with dyspepsia, additional clinical investigations may identify an underlying organic disease that is the likely cause of the symptoms. In these persons, dyspeptic symptoms are attributable to an organic cause of dyspepsia (Table 13-2). In most people with dyspeptic symptoms, however, no organic abnormality is identified by a routine clinical evaluation, and patients who have undergone a diagnostic investigation (including endoscopy) and have not been found to have an obvious specific cause of their symptoms are said to have functional dyspepsia. The term uninvestigated dyspepsia refers to dyspeptic symptoms in persons in whom no diagnostic investigations have yet been performed and in whom a specific diagnosis that explains the dyspeptic symptoms has not been determined.

Table 13-2 Causes of Dyspepsia

| Luminal Gastrointestinal Tract |

|

Gastroparesis (e.g., diabetes mellitus, postvagotomy, scleroderma, chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, postviral, idiopathic)

|

ORGANIC CAUSES OF DYSPEPSIA

The most important identifiable causes underlying dyspeptic symptoms are peptic ulcer disease and GERD. Malignancies of the upper gastrointestinal tract and celiac disease are less common but important causes of dyspeptic symptoms (see Table 13-2).6–10 The investigation of choice in persons with dyspeptic symptoms is endoscopy, which may identify erosive esophagitis, peptic ulcer, or gastric or esophageal cancer.

Systematic studies indicate that approximately 20% of patients with dyspeptic symptoms have erosive esophagitis, 20% have endoscopy-negative GERD, 10% have peptic ulcer, 2% have Barrett’s esophagus, and 1% or less have malignancy.6 Minor findings such as duodenitis or gastritis do not seem to correlate with the presence or absence of dyspeptic symptoms.

INTOLERANCE TO FOOD OR DRUGS

Contrary to popular beliefs, ingestion of specific foods such as spices, coffee, or alcohol, or of excessive amounts of food, has never been established as causing dyspepsia.11,12 Although ingestion of food often aggravates dyspeptic symptoms, this effect probably is related to the sensorimotor response to food rather than to specific food intolerances or allergies. Studies have shown that acute ingestion of capsaicin induces dyspeptic symptoms in healthy persons and in those with functional dyspepsia, with greater intensity in the latter group.13

Dyspepsia is a common side effect of many drugs, including iron, antibiotics, narcotics, digitalis, estrogens and oral contraceptives, theophylline, and levodopa. Medications may cause symptoms through direct gastric mucosal injury, changes in gastrointestinal sensorimotor function, provocation of gastroesophageal reflux, or idiosyncratic mechanisms. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have received the most attention because of their potential to induce ulceration in the gastrointestinal tract. Chronic use of aspirin and other NSAIDs may provoke dyspeptic symptoms in up to 20% of persons, but the occurrence of dyspepsia correlates poorly with the presence of an ulcer. In controlled trials, dyspepsia develops in 4% to 8% of persons treated with NSAIDs, with odds ratios ranging from 1.1 to 3.1 compared with placebo; the magnitude of this effect depends on the dose and type of NSAID.14 Compared with NSAIDs, selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors are associated with a lower frequency of dyspepsia and peptic ulceration.15

PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Peptic ulcer is a well-established cause of dyspeptic symptoms and is an important consideration for clinicians in the management of patients who present with dyspepsia. The frequency of peptic ulcer in patients with dyspepsia, however, is only 5% to 10%.6,10,14 Increasing age, NSAID use, and Helicobacter pylori infection are the main risk factors for peptic ulcer (see Chapters 50 and 52).

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Erosive esophagitis is a diagnostic marker for GERD, but many patients with symptoms that are attributable to the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus have no endoscopic signs of esophageal erosion; this is referred to as nonerosive GERD. Erosive esophagitis is found in approximately 20% of dyspeptic patients, and a similar number of patients may have nonerosive GERD (see Chapter 43).6,10

GASTRIC AND ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

The risk of gastric or esophageal malignancy in patients with dyspeptic symptoms is estimated to be less than 1%.9 The risk of gastric cancer is increased among persons with H. pylori infection, persons with a family history of gastric malignancy, persons with a previous history of gastric surgery, and immigrants from areas endemic for gastric malignancy. The risk of esophageal cancer is increased in men, smokers, persons with a high consumption of alcohol, and those with a long-standing history of heartburn (see Chapters 46 and 54).

PANCREATIC AND BILIARY TRACT DISORDERS

Despite the high prevalence of dyspepsia and gallstones in adults, epidemiologic studies have confirmed that cholelithiasis is not associated with dyspepsia. Therefore, patients with dyspepsia should not be investigated routinely for cholelithiasis, and cholecystectomy in patients with cholelithiasis is not indicated for dyspepsia alone. The clinical presentation of biliary pain is easily distinguishable from that of dyspepsia (see Chapter 65).

Pancreatic disease is less prevalent than cholelithiasis, but symptoms of acute or chronic pancreatitis or of pancreatic cancer may initially be mistaken for dyspepsia. Pancreatic disorders, however, are usually associated with more severe pain and are often accompanied by anorexia, rapid weight loss, or jaundice (see Chapters 58 to 60).

OTHER GASTROINTESTINAL AND SYSTEMIC DISORDERS

Several gastrointestinal disorders may cause dyspepsia-like symptoms. These include infectious (e.g., Giardia lamblia and Strongyloides stercoralis parasites, tuberculosis, fungal infections, syphilis), inflammatory (e.g., celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, lymphocytic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis), and infiltrative (e.g., lymphoma, amyloidosis, Ménétrier’s disease) disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Most of these causes will be identifiable by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with mucosal biopsies. Recurrent gastric volvulus and chronic mesenteric or gastric ischemia may present with dyspeptic symptoms (see Chapters 27, 29, 35, 47, 104, 109, 111, and 114).

The symptom pattern associated with gastroparesis (idiopathic, drug-induced, or secondary to metabolic, systemic, or neurologic disorders) is similar to dyspepsia, and the distinction between idiopathic gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia with delayed gastric emptying (see later) is not well-defined (see Chapter 48).

Finally, dyspepsia may be the presenting or accompanying symptom of acute myocardial ischemia, pregnancy, acute or chronic kidney disease, thyroid dysfunction, adrenal insufficiency, and hyperparathyroidism (see Chapters 35 and 38).

FUNCTIONAL DYSPEPSIA

THE DYSPEPSIA SYMPTOM COMPLEX

Pattern and Heterogeneity

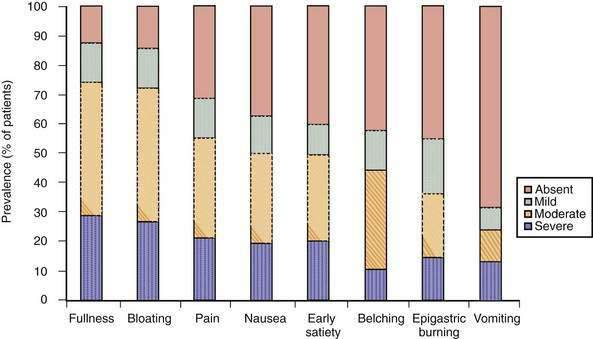

The dyspepsia symptom complex is broader than the four cardinal symptoms that constitute the Rome III definition. It includes multiple symptoms such as epigastric pain, bloating, early satiation, fullness, epigastric burning, belching, nausea, and vomiting. Although often chronic, the symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia are mostly intermittent, even during highly symptomatic episodes.3,16 In persons with functional dyspepsia who present to a tertiary care center, the most frequent symptoms are postprandial fullness and bloating, followed by epigastric pain, early satiation, nausea, and belching.17–20 Heterogeneity of symptoms is considerable, however, as shown, for example, in the number of symptoms that patients report (Fig. 13-1). In the general population, the most frequent dyspeptic symptoms are postprandial fullness, early satiation, upper abdominal pain, and nausea.21–23

Weight loss is traditionally considered an alarm symptom, pointing toward potentially serious organic disease. Patients with functional dyspepsia who present to a tertiary care center also have a high frequency of unexplained weight loss,17,18 and population-based studies in Australia and in Europe have established an association between uninvestigated dyspepsia and unexplained weight loss.22,23

Subgroups

The heterogeneity of the dyspepsia symptom complex is well accepted. Factor analyses of dyspepsia symptoms in the general population and in patients who present to a tertiary care center have not supported the existence of functional dyspepsia as a homogeneous (i.e., unidimensional) condition.22–24 These studies confirmed the heterogeneity of the dyspepsia symptom complex but did not provide clinically meaningful subdivisions of the syndrome.

Several attempts have been made to identify clinically meaningful dyspepsia subgroups to simplify the intricate heterogeneity of the dyspepsia symptom complex and to guide management. The Rome II consensus committee proposed a classification based on a predominant symptom of pain or discomfort. Although correlations were found between the two subdivisions and the presence or absence of H. pylori infection, the absence or presence of delayed gastric emptying, and response or lack of response to gastric acid suppressive therapy,25,26 the subdivisions have been criticized because of the difficulty in distinguishing pain from discomfort, the lack of a widely accepted definition of predominant, uncertainty concerning overlap between the symptom subgroups, the lack of an association with putative pathophysiologic mechanisms and, especially, the lack of stability of the predominant symptom over short time periods.5,27–30

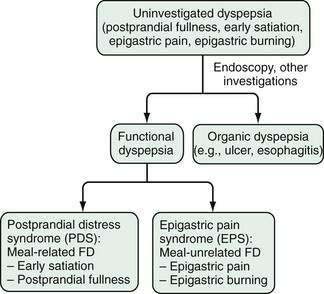

The Rome III consensus committee has proposed different subdivisions (Fig. 13-2). Studies of patients referred to a tertiary care center and of patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia in the general population have revealed that between 40% and 75% of dyspeptic persons report aggravation of symptoms after ingestion of a meal.23,31,32 Assuming that a distinction between meal-related and meal-unrelated symptoms might be pathophysiologically and clinically relevant, the Rome III consensus committee proposed that functional dyspepsia be used as an umbrella term and that postprandial distress syndrome (PDS; meal-related dyspeptic symptoms, characterized by postprandial fullness and early satiation) be distinguished from the epigastric pain syndrome (EPS; meal-unrelated dyspeptic symptoms, characterized by epigastric pain and epigastric burning; Table 13-3).5 Few studies have evaluated the Rome III–based classification of functional dyspepsia. One study of postprandial symptom patterns in persons with functional dyspepsia has provided some support for the distinction between EPS and PDS,32 and a population-based study confirmed the existence of the two distinct subgroups, with less than anticipated overlap between EPS and PDS.33 On the other hand, an open-access endoscopy-based study found considerable overlap in endoscopic findings between patients with EPS or PDS and a large group of dyspeptic patients who were not classified with either.34 The validity of the Rome III classification will have to be assessed in additional ongoing and future studies.

Table 13-3 Classification of and Diagnostic Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia, Postprandial Distress Syndrome, and Epigastric Pain Syndrome*

| Functional Dyspepsia† |

| Includes one or more of the following: |

* According to the Rome III committee.

† Criteria fulfilled for the previous 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

Adapted from Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al, editors. Rome III. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean, Va: Degnon Associates; 2006; pp 427-428.

Overlap with Heartburn and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The issue of overlap of dyspepsia with GERD has been a challenging one. Although earlier investigators considered a group of patients with reflux-like dyspepsia,4 the Rome committees did not consider heartburn to arise primarily from the gastroduodenal region, and this symptom was thus excluded from the definition of dyspepsia.2,5 Heartburn commonly occurs along with dyspeptic symptoms, however, both in the general population and in those with a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.23,27,35 Nevertheless, separating GERD from dyspepsia is hampered by a number of confounding factors, such as the presence of dyspepsia-type symptoms in many patients with GERD36 and difficulties in recognizing heartburn by patients and physicians.37,38

The Rome II consensus committee stated that patients with typical heartburn as a dominant complaint almost invariably have GERD and should be distinguished from patients with dyspepsia.2 Although this distinction is probably valid, it has become clear that the predominant symptom approach does not reliably identify or exclude patients with GERD. The Rome III consensus committee has proposed identification of patients with frequent heartburn, and the suggestion has been made that a word-picture questionnaire be used to facilitate recognition of heartburn by patients and to identify patients with functional dyspepsia who may respond to acid suppressive therapy or in whom pathologic esophageal acid exposure can be demonstrated.39,40 Whereas the Rome II definition for functional dyspepsia excluded patients with predominant heartburn and was unclear about those with nonpredominant heartburn, the Rome III definition stated that heartburn is not a gastroduodenal symptom, although it often occurs simultaneously with symptoms of functional dyspepsia and its presence does not exclude the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.5 Similarly, the frequent co-occurrence of functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)41 is explicitly recognized and does not exclude a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Dyspeptic symptoms are common in the general population, with frequencies ranging from 10% to 45%.11,16,23,27,42–44 The frequency of dyspepsia is slightly higher in women, and the influence of age varies among studies. The results of prevalence studies are strongly influenced by the criteria used to define dyspepsia, and several studies included patients with typical symptoms of GERD or did not take into account the presence of dyspepsia-like symptoms in many patients with GERD. When heartburn is excluded, the frequency of uninvestigated dyspepsia in the general population is in the range of 5% to 15%.43,44 Long-term follow-up studies have suggested improvement or resolution of symptoms in approximately half of patients. The annual incidence rate of dyspepsia has been estimated to range from 1% to 6%.

Quality of life is significantly affected by dyspepsia, especially functional dyspepsia. Although most patients do not seek medical care, a significant proportion will eventually proceed with a consultation, constituting a major impact on the cost of care.16,45–47 Factors that influence health care–seeking are the severity of symptoms, fear of underlying serious disease, psychological distress, and lack of adequate psychosocial support (see later).48

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Several pathophysiologic mechanisms have been suggested to underlie functional dyspeptic symptoms. These suggested mechanisms include delayed gastric emptying, impaired gastric accommodation to a meal, hypersensitivity to gastric distention, altered duodenal sensitivity to lipids or acid, abnormal intestinal motility, and central nervous system dysfunction.3 The heterogeneity of functional dyspepsia seems to be confirmed in the contribution of one or more of these disturbances in subgroups of patients. The studies that have investigated the pathophysiologic mechanisms of functional dyspepsia predate the Rome III consensus committee and classification. Therefore, most studies define functional dyspepsia according to the Rome I and II consensus definitions.

Delayed Gastric Emptying

Several studies have investigated gastric emptying and its relationship to the pattern and severity of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. The frequency of delayed gastric emptying has ranged from 20% to 50%.3,5 In a meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 868 dyspeptic patients and 397 control subjects, a significant delay in gastric emptying of solids was present in almost 40% of patients with functional dyspepsia.49 Most of the studies, however, were performed in small groups of patients with small groups of control subjects. In the largest studies, gastric emptying of solids was delayed in about 30% of the patients with functional dyspepsia. Most studies failed to find a convincing relationship between delayed gastric emptying and the pattern of symptoms. Three large-scale single-center studies from Europe have shown that patients with delayed gastric emptying for solids are more likely to report postprandial fullness, nausea, and vomiting,20,50,51 although two other large multicenter studies in the United States found no or a very weak association.52,53 Whether delayed gastric emptying causes symptoms or is an epiphenomenon is a matter of ongoing controversy.

Impaired Gastric Accommodation

The motor functions of the proximal and distal stomach differ remarkably. Whereas the distal stomach regulates gastric emptying of solids by grinding and sieving the contents until the particles are small enough to pass the pylorus, the proximal stomach serves mainly as a reservoir during and after ingestion of a meal. Accommodation of the stomach to a meal results from a vagally mediated reflex relaxation of the proximal stomach that provides the meal with a reservoir and enables the stomach to handle large intragastric volumes without a rise in intragastric pressure.54

Studies using a gastric barostat, scintigraphy, ultrasonography, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), or noninvasive surrogate markers (e.g., satiety drinking test) have all suggested the presence of impaired gastric accommodation in approximately 40% of patients with functional dyspepsia.3,5,17,19,54 Insufficient accommodation of the proximal stomach during and after the ingestion of a meal may be accompanied by increased intragastric pressure and activation of mechanoreceptors in the gastric wall, thus inducing symptoms. Although a number of studies found associations between impaired accommodation and both early satiation and weight loss, other studies failed to find such associations. In addition, the mechanisms whereby impaired accommodation can be a cause of symptoms is still unclear; meal ingestion in the absence of proper relaxation of the proximal stomach may be accompanied by activation of tension-sensitive mechanoreceptors in the proximal stomach. On the other hand, insufficient accommodation of the proximal stomach may force the meal into the distal stomach, thereby causing activation of tension-sensitive mechanoreceptors in a distended antrum.

Hypersensitivity to Gastric Distention

Visceral hypersensitivity, defined as abnormally enhanced perception of visceral stimuli, is considered one of the major pathophysiologic mechanisms in the functional gastrointestinal disorders (see Chapters 11, 21, and 118).55 Several studies have established that as a group, patients with functional dyspepsia are hypersensitive to isobaric gastric distention.3,5,18 The level at which visceral hypersensitivity is generated is unclear, and evidence exists for involvement of tension-sensitive mechanoreceptors as well as alterations at the level of visceral afferent nerves or of the central nervous system.56–58

Altered Duodenal Sensitivity to Lipids or Acid

In healthy subjects and in persons with functional dyspepsia, duodenal perfusion with nutrient lipids, but not glucose, enhances the perception of gastric distention through a mechanism that requires lipid digestion and subsequent release of cholecystokinin.59–61 Duodenal infusion of hydrochloric acid induces nausea in persons with functional dyspepsia but not in healthy subjects, thereby suggesting duodenal hypersensitivity to acid.62 Duodenal pH monitoring using a clipped pH electrode has revealed increased postprandial duodenal acid exposure in patients with functional dyspepsia compared with controls, and this difference has been attributed to impaired clearance of acid.63 On the basis of these observations, it has been proposed that increased duodenal sensitivity to lipids or acid may contribute to the generation of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, but further research in this area is needed.

Other Mechanisms

One study has reported a high frequency of rapid gastric emptying in patients with functional dyspepsia; rapid gastric emptying was correlated with postprandial symptom intensity.64 Other studies that evaluated rapid emptying, however, failed to find such a high frequency or correlation.20,32

Phasic fundic contractions induce transient increases in gastric wall tension, which can be perceived by patients with functional dyspepsia.57 One study has reported lack of suppression of phasic contractility of the proximal stomach after a meal in a subset of patients with functional dyspepsia.65

Evidence also exists that abnormalities in the control of gastric myoelectrical activity, as measured by cutaneous electrogastrography, are found in up to two thirds of patients with functional dyspepsia.66,67 No correlation was found between the symptom pattern and presence of electrogastrographic findings.

Small intestinal motor alterations, usually hypermotility with burst activity or clusters and an increased proportion of duodenal retrograde contractions (see Chapter 97), have been reported in patients with functional dyspepsia, but no clear correlation with symptoms has been found.68

PATHOGENIC FACTORS

Genetic Predisposition

Population studies have suggested that genetic factors contribute to functional dyspepsia. The risk of dyspepsia is increased in first-degree relatives of patients compared with their spouses.69 In a case-control study, polymorphisms of the GNB3 gene that encodes guanine nucleotide binding protein, beta polypeptide 3 (especially the homozygous GNB3 825C state), were associated with symptoms of functional dyspepsia in blood donors and patients.70 Subsequently, a community-based study in the United States reported that both homozygous variants (CC and TT) of GNB3 were associated with meal-unrelated dyspepsia.71

Infection

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Depending on the region and population studied, a variable proportion of patients with functional dyspepsia are infected with H. pylori.3,5 Although H. pylori is associated with a number of organic causes of dyspepsia, little evidence supports a causal relationship between H. pylori infection and functional dyspepsia.72 No consistent differences in the pattern of symptoms or putative pathophysiologic mechanisms have been found between H. pylori–positive and H. pylori–negative subjects.73 The best evidence in support of a role for H. pylori in functional dyspepsia is the small but statistically significant beneficial effect of eradication therapy on symptoms (see later).74

Postinfection Functional Dyspepsia

Postinfection functional dyspepsia has been proposed as a possible clinical entity on the basis of a large retrospective study from a tertiary referral center.19 Compared with patients who had functional dyspepsia of unspecified onset, patients with a history suggestive of postinfection functional dyspepsia were more likely to report symptoms of early satiation, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting and had a significantly higher frequency of impaired accommodation of the proximal stomach, which was attributed to dysfunction at the level of gastric nitrergic (nitroxidergic) neurons.19 In a prospective cohort study, development of functional dyspepsia was increased fivefold in patients one year after acute Salmonella gastroenteritis compared with subjects who did not have gastroenteritis.75 Additional studies are required to identify the underlying pathophysiology and risk factors and to determine the long-term prognosis.

Psychosocial Factors

Review of the literature clearly reveals an association between psychosocial factors and functional dyspepsia.3,5,76–80 The most common psychiatric comorbidities in patients with functional dyspepsia are anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, somatoform disorders, and a recent or remote history of physical or sexual abuse.79,80 Psychological distress has long been assumed to be a feature of health care–seeking behavior in patients with functional bowel disorders, including functional dyspepsia. Studies have confirmed an association between dyspeptic symptoms in the general population and psychosocial factors such as somatization, anxiety, and life event stress; this association argues against a mere health care–seeking effect.31,81 Furthermore, the severity of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia seen in a tertiary care center is more strongly related to psychosocial factors (especially depression, abuse history, and somatization) than to abnormalities of gastric sensorimotor function (see Chapter 21).82

Although these observations show a close interaction between different psychosocial variables and the presence and severity of symptoms of functional dyspepsia, they do not establish whether the psychosocial factors and dyspeptic symptoms are manifestations of a common predisposition or whether the psychosocial factors play a causal role in the pathophysiology of dyspeptic symptoms. The relationship is unlikely to be simple. A factor analysis of symptoms of functional dyspepsia and their relationship with pathophysiology and psychopathology has clearly demonstrated the heterogeneity and complexity of these interactions. It identified four separate functional dyspeptic symptom factors, of which the factor consisting of epigastric pain was associated with visceral hypersensitivity, several psychosocial dimensions, including somatization and neuroticism, and low health-related quality of life.24

These observations suggest a relationship between psychosocial factors and visceral hypersensitivity in particular. Acutely induced anxiety in healthy volunteers, however, was not associated with increased visceral sensitivity but with decreased gastric compliance and a significant inhibition of meal-induced accommodation.83 In patients with functional dyspepsia, a correlation between anxiety and gastric sensitivity was found in the subgroup of hypersensitive patients, but not in the group as a whole.84 A history of physical or sexual abuse was associated with visceral hypersensitivity in patients with functional dyspepsia.85 Clearly, the role of psychosocial factors in the generation and severity of symptoms, especially in terms of their impact on clinical management, requires further study.

APPROACH TO UNINVESTIGATED DYSPEPSIA

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Specific attention should be given to a history of heartburn, and a word-picture questionnaire may help the patient recognize the typical symptom pattern.37 Burning pain confined to the epigastrium is a cardinal symptom of dyspepsia and is not considered to be heartburn unless the pain radiates retrosternally. The presence of frequent and typical reflux symptoms should lead to a provisional diagnosis of GERD rather than dyspepsia, and the patient should initially be managed as a patient with GERD (see Chapter 43). On the other hand, overlap of GERD with dyspepsia is probably frequent and needs to be considered when symptoms do not respond to appropriate management of GERD. The possible presence of overlapping IBS should also be assessed, and symptoms that improve with bowel movements or are associated with changes in stool frequency or consistency should lead to a presumptive diagnosis of IBS.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

In most cases, the patient’s history and physical examination will allow dyspepsia to be distinguished from symptoms suggestive of esophageal, pancreatic, or biliary disease. The history and physical findings, and even the presence of alarm symptoms, are unreliable for distinguishing functional from organic causes of dyspepsia by primary care physicians and by gastroenterologists.6,9,10,86,87 Therefore, most guidelines and recommendations advocate prompt endoscopy when risk factors such as NSAID use, age above a certain threshold, or alarm symptoms are present.88–90 The optimal management strategy for most patients who do not have a risk factor for an organic cause of dyspepsia remains a matter of debate and controversy, and several approaches have been proposed. The options include the following: (1) prompt diagnostic endoscopy, followed by targeted medical therapy; (2) noninvasive testing for H. pylori infection, followed by treatment based on the result (test and treat strategy); and (3) empirical antisecretory therapy. In the two latter strategies, endoscopy is performed in patients who do not respond to treatment or who experience recurrent symptoms after treatment.

Prompt Endoscopy and Directed Treatment

Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy allows direct recognition of organic causes of dyspepsia such as peptic ulcer, erosive esophagitis, or malignancy. Endoscopy before any therapy has been instituted is still considered the diagnostic gold standard for patients with an upper gastrointestinal disorder.91 The procedure may also have a reassuring effect on physicians and patients.92–94 Gastric mucosal biopsies allow the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, with subsequent eradication therapy if the result is positive. Endoscopy is claimed to permit diagnosis of early gastric cancer at a curable stage, but detecting early gastric cancer in a symptomatic individual is relatively rare, and evidence for the claim is weak.95–97

A number of randomized controlled trials have compared prompt endoscopy with empirical noninvasive management strategies. A meta-analysis of five trials that compared initial endoscopy with a test and treat strategy has concluded that initial endoscopy may be associated with a small reduction in the risk of recurrent dyspeptic symptoms but that this gain is not cost-effective.98 Most relevant studies found that the direct and indirect costs are higher with prompt endoscopy and that these costs are not completely offset by a reduction in medication use or the number of subsequent physician visits.99–101 The available data, therefore, do not support early endoscopy as a cost-effective initial management strategy for all patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia.

Nevertheless, most available practice guidelines advocate initial endoscopy in all patients above a certain age threshold, usually 45 to 55 years, to detect a potentially curable upper gastrointestinal malignancy.88–90 The rationale for this approach is that the vast majority of gastric malignancies occur in patients older than 45 years and that the rate of cancer detection rises in persons with dyspepsia older than age 45.95–97 Most patients with newly diagnosed gastric cancer, however, are already incurable at the time of diagnosis, and many will have some alarm features that would have warranted immediate endoscopy.97 Early endoscopy is also recommended in patients younger than 45 years who have a family history of gastric cancer, emigrated from a country with a high rate of gastric cancer, or had a prior partial gastrectomy.

Test and Treat for H. pylori Infection

H. pylori infection is causally associated with most peptic ulcers and is the most important risk factor for gastric cancer.102 Because of the involvement of H. pylori in peptic ulcer disease, several consensus panels have advocated noninvasive testing for H. pylori in young patients (younger than 45 to 55 years) with uncomplicated dyspepsia. Patients with a positive test result receive eradication therapy (a proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics, such as amoxicillin and clarithromycin, taken for 7 to 14 days (see Chapter 50), whereas patients with a negative test result are treated empirically, usually with a proton pump inhibitor. The benefits of this test and treat strategy are the cure of peptic ulcer disease or prevention of future peptic ulcers and symptom resolution in a small subset (approximately 7% above the rate with placebo) of patients with functional dyspepsia who are infected with H. pylori.74,103 Eradication of H. pylori eliminates chronic gastritis and, in theory, may thereby contribute to a reduction in the risk of H. pylori–associated gastric cancer.104

On the other hand, in Western countries, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia is rapidly declining, and infection rates are especially low in persons younger than 30 years (10% to 30%). Widespread use of antibiotics has the disadvantages of inducing resistance and occasionally causing allergic reactions. Whether eradication of H. pylori causes or worsens GERD has not been proved and is an ongoing matter of debate.102,105 Furthermore, the accuracy of noninvasive testing for H. pylori depends on the prevalence of H. pylori in the population as well as the sensitivity and specificity of the test. Serologic tests are the least expensive but also the least accurate. If the prevalence of H. pylori in a population is less than 60%, the fecal antigen and urea breath tests for H. pylori are preferred, because their higher accuracy rates lead to a reduction in inappropriate treatment for patients without H. pylori infection (see Chapter 50).106

Randomized placebo-controlled trials have shown only a modest reduction in symptoms of dyspepsia after a test and treat approach in primary care.107–109 A meta-analysis of studies that compared a test and treat strategy with empirical antisecretory therapy in persons with uninvestigated dyspepsia has found little difference in symptom resolution or costs between the two approaches.110 Although earlier models that assumed a higher prevalence rate of H. pylori infection suggested a greater benefit to a test and treat approach,111–113 subsequent economic models have suggested that the test and treat strategy may be equally or less cost-effective than empirical antisecretory therapy.114,115 The test and treat strategy as an initial approach is most likely to be beneficial in areas where the H. pylori infection rate is high.

Empirical Antisecretory Therapy

Initial empirical antisecretory therapy is widely used in primary care for patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia. This approach is attractive because it controls symptoms and heals lesions in most patients with underlying GERD or peptic ulcer disease, and may provide symptomatic benefit in up to one third of patients with functional dyspepsia.116,117 Proton pump inhibitors provide symptomatic relief superior to that of histamine H2 receptor agonists, and the response usually occurs within two weeks of initiating therapy.99

Disadvantages of empirical proton pump inhibitor therapy are a rapid relapse in symptoms after cessation of therapy and the potential for rebound gastric hypersecretion when therapy is discontinued.115,116 Many patients, therefore, will continue to take proton pump inhibitor therapy chronically.

As noted earlier, a meta-analysis of studies that compared a test and treat strategy with empirical antisecretory therapy in persons with dyspepsia found little difference in symptom resolution or costs between the two strategies.110 Empirical antisecretory therapy may be equally or more cost-effective.114,115

ADDITIONAL INVESTIGATIONS

In cases of severe postprandial fullness, and especially in cases of refractory nausea and vomiting, gastric emptying testing using scintigraphy or a breath test can be considered (see Chapter 48). In cases of a severe delay in gastric emptying, a small bowel series can rule out mechanical obstruction as a contributing factor. In cases of refractory intermittent pain or epigastric burning, esophageal pH with impedance monitoring is useful for diagnosing atypical manifestations of GERD that is not responsive to empirical antisecretory therapy (see Chapter 43). Psychological or psychiatric assessment is recommended in cases of long-standing refractory or debilitating symptoms. Electrogastrography, barostat studies, or simple nutrient challenge tests have been used in pathophysiologic studies but have no established role in the clinical management of dyspeptic patients.

TREATMENT OF FUNCTIONAL DYSPEPSIA

GENERAL MEASURES

Reassurance and education are of primary importance in patients with functional dyspepsia. In spite of normal findings at endoscopy, the patient should be given a confident and positive diagnosis. In patients with IBS, a positive physician-patient interaction can reduce health care–seeking behavior, and this approach is probably also valid for patients with functional dyspepsia.118

Lifestyle and dietary measures are usually prescribed to patients with functional dyspepsia, but the impact of dietary interventions has not been studied systematically.11 Having patients eat more frequent, smaller meals seems logical. Because the presence of lipids in the duodenum enhances gastric sensitivity, avoiding meals with a high fat content might be advisable.59,60 Similarly, consumption of spicy foods containing capsaicin and other irritants is often discouraged.15 Coffee may aggravate symptoms in some cases119 and, if implicated, should be avoided. Cessation of smoking and alcohol consumption is suggested to be helpful, with no convincing evidence of efficacy.120 The avoidance of aspirin and other NSAIDs is commonly recommended and seems sensible, although not of established value.14,15 If a patient has an apparent coexisting anxiety disorder or depression, appropriate treatment should be considered (see later).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Acid Suppressive Drugs

In patients with gastroesophageal reflux, a trial of antisecretory therapy often has therapeutic and diagnostic value. Based on meta-analyses of therapeutic outcomes in patients with functional dyspepsia, the efficacy of antacids, sucralfate, and misoprostol has not been demonstrated.121 A meta-analysis of 12 randomized placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of H2 receptor antagonists in patients with functional dyspepsia reported a significant benefit over placebo, with a relative risk reduction of 23% and a number needed to treat of 7.121 H2 receptor blockers thus appear to be efficacious in functional dyspepsia. Many of these trials, however, probably included patients with GERD under a broad interpretation of functional dyspepsia, thereby accounting for much of the benefit.

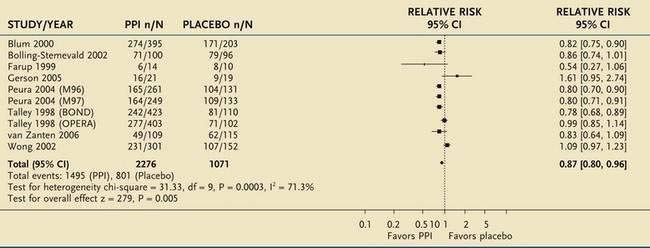

A meta-analysis of eight placebo-controlled, randomized trials of proton pump inhibitors for functional dyspepsia also confirmed that this class of agents was superior to placebo, with a number needed to treat of 10 (Table 13-4).121,122 The relative risk reduction (13%) was lower than that for H2 receptor blockers, probably reflecting more stringent entry criteria and better exclusion of patients with GERD. No difference in efficacy was found between half-dose and full-dose proton pump inhibitors, and a double dose of a proton pump inhibitor was also not superior to a single dose. H. pylori status did not affect the response to proton pump inhibitor therapy. Subgrouping of patients with functional dyspepsia using Rome definitions showed a trend for proton pump inhibitor therapy to be most effective in the group with overlapping dyspepsia and reflux, less effective in those with only epigastric pain, and ineffective in those with dysmotility.

Table 13-4 Meta-Analysis of 10 Randomized Controlled Trials of Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Therapy in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia

From Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4):CD001960.

*For each trial, n/N represents the proportion of nonresponders (n) over the total number of patients in that group (N).

CI, confidence interval.

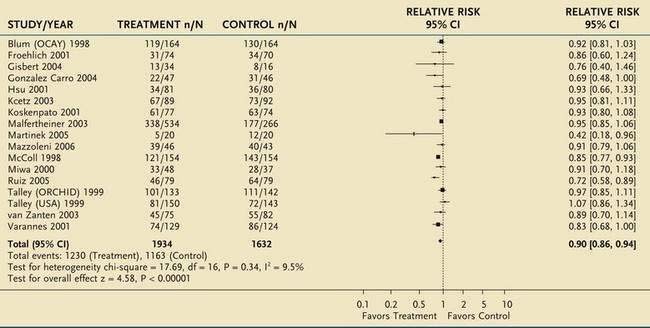

Eradication of H. pylori Infection

A Cochrane meta-analysis has reported a 10% pooled relative risk reduction in dyspepsia for therapy to eradicate H. pylori infection, compared with placebo, at 12 months of follow-up, with a number needed to treat of 14 (Table 13-5).74 Arguments against eradication therapy are the low number of responders and the delayed occurrence of a demonstrable symptomatic benefit. On the other hand, H. pylori eradication can induce sustained remission in dyspepsia, albeit in a small minority of patients.123 Other arguments in favor of the use of eradication therapy are protection against peptic ulcer, presumed protection against gastric cancer, and short-term nature and relatively low cost of the treatment.

Table 13-5 Meta-Analysis of 12 Randomized Controlled Trials of Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Patients with Functional Dyspepsia

From Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (2):CD002096.

*For each trial, n/N represents the proportion of nonresponders (n) over the total number of patients in that group (N).

CI, confidence interval.

Prokinetic Agents

Gastric prokinetic agents are a heterogeneous class of compounds that act through different types of receptors. The efficacy of available prokinetic agents in functional dyspepsia has been controversial.121,124,125 A meta-analysis, based mainly on studies of domperidone and cisapride, suggested superiority of prokinetic agents over placebo in patients with functional dyspepsia, with a relative risk reduction of 33% and a number needed to treat of six121; separate analyses have also suggested efficacy for cisapride and domperidone individually.124 Metoclopramide and domperidone are dopamine receptor agonists with a stimulatory effect on upper gastrointestinal motility. Unlike metoclopramide, which may cause serious neurologic adverse effects, domperidone—which is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration—does not cross the blood-brain barrier. Cisapride facilitates the release of acetylcholine in the myenteric plexus via 5-hydroxytryptamine4 (5-HT4) receptor agonism and accelerates gastric emptying. The available trials with these drugs, however, were often of poor quality, concerns were raised about publication bias, and cisapride has been withdrawn from the market because of cardiac safety concerns.121

Unfortunately, more recent studies with other types of prokinetic agents have generally not demonstrated symptomatic relief in patients with functional dyspepsia.125 The motilin receptor agonist, ABT-229, was actually found to worsen symptoms compared with placebo.126 Mosapride, which like cisapride is a mixed 5-HT4 receptor agonist and 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, demonstrated no benefit when compared with placebo in a large European study.127 The 5-HT4 receptor agonist tegaserod, 6 mg twice daily, was evaluated in two phase 3 randomized controlled trials in women with dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia. The two primary endpoints were the percentage of days with satisfactory symptom relief and the symptom severity on a composite average daily severity score. Statistical significance for both endpoints was obtained in one study but not in the other, and the overall therapeutic gain was small.128 The drug was well tolerated in this program but was withdrawn from the market because of an increased frequency of cardiovascular ischemic events. Itopride is a dopamine D2 antagonist and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that was intensively studied in functional dyspepsia. A phase 2 placebo-controlled trial found significantly more responders to itopride, based on a global efficacy measure.129 No significant improvement in symptoms compared with placebo was observed, however, in two subsequent phase 3 trials.130

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are commonly used for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders that do not respond to initial conventional approaches. Although systematic reviews suggest that anxiolytics and antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressants, may have some benefit in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders, including functional dyspepsia (pooled relative risk reduction of 45%), the available trials are small and of poor quality, and publication bias cannot be excluded.131,132 A multicenter controlled trial of the tricyclic antidepressant desipramine in patients with functional bowel disorders failed to show benefit in an intention-to-treat analysis, but symptomatic improvement was obtained in a per-protocol analysis.133 Most of the enrolled patients, however, seemed to have IBS, and the number of patients with functional dyspepsia in the trial is unclear. The mechanism of action of antidepressants is also unclear; symptomatic relief from these medications appears to be independent of the presence of depression,133 and no significant effects of antidepressants on visceral sensitivity have been established in functional dyspepsia.134,135 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine enhanced gastric accommodation in healthy subjects, but clinical studies evaluating this class of agents in functional dyspepsia are lacking. A large controlled trial with the selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine in functional dyspepsia failed to show any benefit.135

Other Pharmacotherapeutic Approaches

Based on a meta-analysis of four trials, bismuth salts seemed efficacious, but the analysis had marginal statistical significance.121 Simethicone was superior to placebo in one controlled trial.136 Various studies reported an improvement in symptoms during treatment with mixed herbal preparations, Chinese herbal preparations, or artichoke leaf extract.137–139 The data suggest that some of these preparations are effective, but the basis for the improvement remains to be determined. One study reported that the chronic administration of red pepper was more effective than placebo in decreasing the intensity of dyspeptic symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia.140

New Drug Development

Fundic relaxants and visceral analgesics to reverse impaired gastric accommodation and visceral hypersensitivity are other attractive approaches for treating sensorimotor disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Although nitrates, sildenafil, and sumatriptan can relax the proximal stomach, they seem less suitable for therapeutic application in functional dyspepsia.54,125 A number of serotonergic drugs are also able to enhance gastric accommodation, including 5-HT1A, 5-HT3, and 5-HT4 receptor agonists.54,125 A clinical trial with a newly developed 5-HT1A receptor agonist R137696 in functional dyspepsia failed to show any symptomatic benefit.141 Acotiamide (Z-338) is a novel compound that enhances acetylcholine release via antagonism of the M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors (see Chapter 49). In a pilot study, acotiamide showed potential to improve symptoms and quality of life through a mechanism that may involve enhanced accommodation.142

Visceral hypersensitivity is another attractive target for drug development. The principal drug classes under evaluation are neurokinin receptor antagonists and peripherally acting kappa opioid receptor agonists. The kappa opioid agonist fedotozine showed potential efficacy in functional dyspepsia, but development of this drug was discontinued.143 More recently, asimadoline, another kappa opioid receptor agonist, failed to improve symptoms in a small pilot study.144

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Studies have shown that patients with functional dyspepsia have a higher prevalence of psychosocial comorbidities, although the role of psychosocial factors in symptom generation remains unclear. Based in part on these comorbidities, psychological interventions such as group support with relaxation training, cognitive therapy, psychotherapy, and hypnotherapy have been used in patients with functional dyspepsia. A systematic review of clinical trials of psychological interventions for functional dyspepsia found that all trials claimed benefit from psychological interventions, with effects persisting for longer than one year, but all studies were limited by inadequate statistical analysis.145 The authors concluded that the evidence to confirm the efficacy of psychological interventions in functional dyspepsia is insufficient.

RECOMMENDATIONS

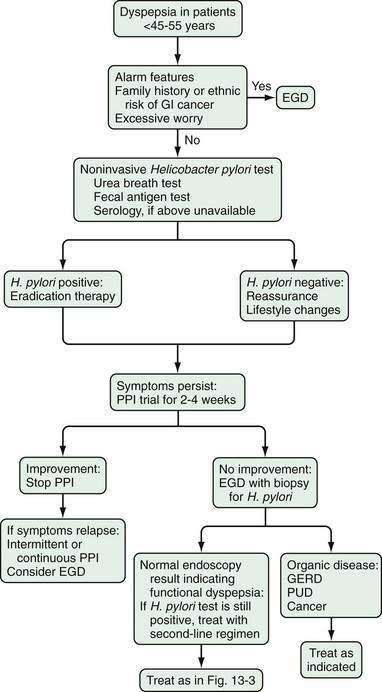

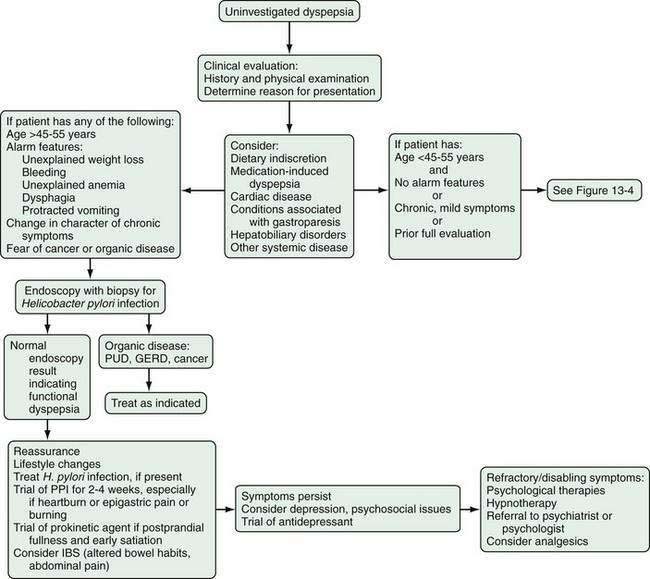

In patients with functional dyspepsia who have mild or intermittent symptoms, reassurance, education, and some dietary changes may be sufficient (Figs. 13-3 and 13-4). Drug therapy can be considered for patients with more severe symptoms or those who do not respond to reassurance and lifestyle changes. Testing for H. pylori infection is recommended and, if the results are positive, eradication therapy can be prescribed. An immediate impact on symptoms is unlikely, however, and any potential benefit is observed mainly over longer follow-up. Both proton pump inhibitors and prokinetic agents can be used as initial pharmacotherapy. The symptom pattern may help in determining the most appropriate initial choice of therapy, but a change in drug class is advisable in case of an insufficient therapeutic response.

Figure 13-3. Management algorithm for patients with dyspepsia. Patients younger than 45 to 55 years who do not have alarm features should be evaluated as in Figure 13-4. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; PUD, peptic ulcer disease.

Bisschops R, Karamanolis G, Arts J, et al. Relationship between symptoms and ingestion of a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2008;57:1495-503. (Ref 32.)

Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: Results of the U.S. Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543-52. (Ref 44.)

Delaney B, Ford AC, Forman D, et al. Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (4):CD001961. (Ref 99.)

Enck P, Dubois D, Marquis P. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms: Results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:48-54. (Ref 45.)

Haycox A, Einarson T, Eggleston A. The health economic impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population: Results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:38-47. (Ref 46.)

Ofman JJ, MacLean CH, Straus WL, et al. Meta-analysis of dyspepsia and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:508-18. (Ref 14.)

Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, et al. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: A systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329-37. (Ref 122.)

Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (2):CD002096. (Ref 74.)

Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4):CD001960. (Ref 121.)

Soo S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al. Psychological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (2):CD002301. (Ref 145.)

Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1239-55. (Ref 3.)

Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-79. (Ref 5.)

Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-80. (Ref 88.)

Talley NJ, Vakil N. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2324-37. (Ref 89.)

Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:390-401. (Ref 9.)

1. Drossman DA, Thompson GW, Talley NJ, et al. Identification of subgroups of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Int. 1990;3:159-72.

2. Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II37-42.

3. Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1239-55.

4. Colin-Jones DG, Bloom B, Bodemar G, et al. Management of dyspepsia. Report of a working party. Lancet. 1988;1:576-9.

5. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-79.

6. Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Fennerty MB, Vakil N. Can the clinical history distinguish between organic and functional dyspepsia? JAMA. 2006;295:1566-76.

7. Bardella MT, Minoli G, Ravizza D, et al. Increased prevalence of celiac disease in patients with dyspepsia. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1489-91.

8. Locke GR3rd, Murray JA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Celiac disease serology in irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia: A population-based case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:476-82.

9. Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:390-401.

10. Hammer J, Eslick GD, Howell SC, et al. Diagnostic yield of alarm features in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2004;53:666-72.

11. Feinle-Bisset C, Vozzo R, Horowitz M, Talley NJ. Diet, food intake, and disturbed physiology in the pathogenesis of symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;99:170-81.

12. Boekema P, Van Dan van Isselt E, Bots ML, Smout A. Functional bowel symptoms in a general Dutch population and associations with common stimulants. Neth J Med. 2001;59:23-30.

13. Hammer J, Führer M, Pipal L, Matiasek J. Hypersensitivity for capsaicin in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:125-33.

14. Ofman JJ, MacLean CH, Straus WL, et al. Meta-analysis of dyspepsia and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:508-18.

15. Spiegel BM, Farid M, Dulai GS, et al. Comparing rates of dyspepsia with coxibs versus NSAID + PPI: A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;448:e27-36.

16. Agreus L. Natural history of dyspepsia. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 4):iv2-9.

17. Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, et al. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1346-52.

18. Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, et al. Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:526-35.

19. Tack J, Demedts I, Dehondt G, et al. Clinical and pathophysiological characteristics of acute-onset functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1738-47.

20. Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, et al. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:783-8.

21. Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, et al. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: Findings from the DIGEST study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845-54.

22. Jones MP, Talley NJ, Eslick GD, et al. Community subgroups in dyspepsia and their association with weight loss. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2051-60.

23. Piessevaux H, De Winter B, Louis E, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms in the general population: A factor and cluster analysis of symptom groupings. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:378-88.

24. Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Persoons P, et al. Evidence-based subtypes in functional dyspepsia with confirmatory factor analysis: Psychosocial and physiopathological correlates. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:268-76.

25. Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Predominant symptoms identify different subgroups in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2080-5.

26. Talley NJ, Meineche-Schmidt V, Pare P, et al. Efficacy of omeprazole in functional dyspepsia: Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (the Bond and Opera studies). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1055-65.

27. Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: Overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671-80.

28. Laheij RJ, De Koning RW, Horrevorts AM, et al. Predominant symptom behavior in patients with persistent dyspepsia during treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:490-5.

29. Talley NJ, Locke GR, Lahr BD, et al. Predictors of the placebo response in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:923-36.

30. Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Association of the predominant symptom with clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:296-303.

31. Castillo EJ, Camilleri M, Locke GR, et al. A community-based, controlled study of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:985-96.

32. Bisschops R, Karamanolis G, Arts J, et al. Relationship between symptoms and ingestion of a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2008;57:1495-503.

33. Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, et al. Do distinct dyspepsia subgroups exist in the community? A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1983-9.

34. van Kerkhoven LA, Laheij RJ, Meineche-Schmidt V, et al. Functional dyspepsia: Not all roads seem to lead to Rome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:118-22.

35. Locke GR3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Fett SL, et al. Overlap of gastrointestinal symptom complexes in a U.S. community. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:29-34.

36. Madsen LG, Wallin L, Bytzer P. Identifying response to acid suppressive therapy in functional dyspepsia using a random starting day trial—is gastro-oesophageal reflux important? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:423-30.

37. Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1023-9.

38. Dent J. Definitions of reflux disease and its separation from dyspepsia. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 4):IV17-20.

39. Johnsson F, Roth Y, Damgaard Pedersen NE, Joelsson B. Cimetidine improves GERD symptoms in patients selected by a validated GERD questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:81-6.

40. Tack J, Caenepeel P, Arts J, et al. Prevalence of acid reflux in functional dyspepsia and its association with symptom profile. Gut. 2005;54:1370-6.

41. Corsetti M, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, et al. Impact of coexisting irritable bowel syndrome on symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1152-9.

42. El-Serag HB, Talley NJ. Systematic review: The prevalence and clinical course of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:643-54.

43. Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, et al. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: Findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845-54.

44. Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: Results of the U.S. Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543-52.

45. Enck P, Dubois D, Marquis P. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms: Results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:48-54.

46. Haycox A, Einarson T, Eggleston A. The health economic impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population: Results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:38-47.

47. Moayyedi P, Mason J. Clinical and economic consequences of dyspepsia in the community. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 4):iv10-2.

48. Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Predictors of health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and nonulcer dyspepsia: A critical review of the literature on symptom and psychosocial factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1340-9.

49. Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, Lodder AC, et al. Disturbed solid-phase gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia: A meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2028-33.

50. Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036-42.

51. Perri F, Clemente R, Festa V, et al. Patterns of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2082-8.

52. Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Can symptoms discriminate among those with delayed or normal gastric emptying in dysmotility-like dyspepsia? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1422-8.

53. Talley NJ, Locke GR3rd, Lahr BD, et al. Functional dyspepsia, delayed gastric emptying and impaired quality of life. Gut. 2006;23:923-36.

54. Kindt S, Tack J. Impaired gastric accommodation and its role in dyspepsia. Gut. 2006;55:1685-91.

55. Camilleri M, Coulie B, Tack J. Visceral hypersensitivity: Facts, speculations and challenges. Gut. 2001;48:125-31.

56. Tack J, Caenepeel P, Corsetti M, Janssens J. Role of tension receptors in dyspeptic patients with hypersensitivity to gastric distention. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1058-66.

57. Vandenberghe J, Dupont P, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow during gastric balloon distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1684-93.

58. Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Persoons P, et al. Dyspeptic patients with visceral hypersensitivity: Sensitisation of pain specific or multimodal pathways? Gut. 2005;54:914-19.

59. Feinle C, D’Amato M, Read NW. Cholecystokinin-A receptors modulate gastric sensory and motor responses to gastric distension and duodenal lipid. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1379-85.

60. Feinle C, Rades T, Otto B, Fried M. Fat digestion modulates gastrointestinal sensations induced by gastric distention and duodenal lipid in humans. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1100-7.

61. Feinle C, Meier O, Otto B, et al. Role of duodenal lipid and cholecystokinin A receptors in the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2001;48:347-55.

62. Samsom M, Verhagen MA, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Abnormal clearance of exogenous acid and increased acid sensitivity of the proximal duodenum in dyspeptic patients. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:515-20.

63. Lee KJ, Demarchi B, Demedts I, et al. A pilot study on duodenal acid exposure and its relationship to symptoms in functional dyspepsia with prominent nausea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1765-73.

64. Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, et al. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685-94.

65. Simrén M, Vos R, Janssens J, Tack J. Unsuppressed postprandial phasic contractility in the proximal stomach in functional dyspepsia: Relevance to symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2169-75.

66. Pfaffenbach B, Adamek RJ, Bartholomaus C, Wegener M. Gastric dysrhythmias and delayed gastric emptying in patients with functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2094-9.

67. Parkman HP, Miller MA, Trate D, et al. Electrogastrography and gastric emptying scintigraphy are complementary for assessment of dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:214-9.

68. Wilmer A, Van Cutsem E, Andrioli A, et al. Ambulatory gastrojejunal manometry in severe motility-like dyspepsia: Lack of correlation between dysmotility, symptoms, and gastric emptying. Gut. 1998;42:235-4.

69. Locke GR3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, et al. Familial association in adults with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:907-12.

70. Holtmann G, Siffert W, Haag S, et al. G-protein beta 3 subunit 825 CC genotype is associated with unexplained (functional) dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:971-9.

71. Camilleri CE, Carlson PJ, Camilleri M, et al. A study of candidate genotypes associated with dyspepsia in a U.S. community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:581-92.

72. Lai LH, Sung JJ. Helicobacter pylori and benign upper digestive disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:261-79.

73. Sarnelli G, Cuomo R, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptom patterns and pathophysiological mechanisms in dyspeptic patients with and without Helicobacter pylori. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2229-36.

74. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (2):CD002096.

75. Mearin F, Perez-Oliveras M, Perello A, et al. Dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after a Salmonella gastroenteritis outbreak: One-year follow-up cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:98-104.

76. Haug TT, Wilhelmsen I, Berstad A, Ursin H. Life events and stress in patients with functional dyspepsia compared with patients with duodenal ulcer and healthy controls. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:524-30.

77. Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II25-30.

78. Locke GR3rd, Weaver AL, Melton LJ3rd, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: A population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350-7.

79. Magni G, di Mario F, Bernasconi G, Mastropaolo G. DSM-III diagnoses associated with dyspepsia of unknown cause. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1222-3.

80. Haug TT, Svebak S, Wilhelmsen I, et al. Psychological factors and somatic symptoms in functional dyspepsia. A comparison with duodenal ulcer and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:281-91.

81. Locke GR, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: A population-based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350-7.

82. Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, et al. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: Gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors or somatization? Gut. 2008;57:1666-73.

83. Geeraerts B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, et al. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1437-44.

84. Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, et al. Relationship between anxiety and gastric sensorimotor function in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:455-63.

85. Geeraerts B, van Oudenhove L, Fischler B, et al. Influence of abuse history on gastric sensorimotor function in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:33-41.

86. Value of the unaided clinical diagnosis in dyspeptic patients in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1417-21.

87. Heikkinen M, Pikkarainen P, Eskelinen M, Julkunen R. GP’s ability to diagnose dyspepsia based only on physical examination and patient history. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2000;18:99-104.

88. Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-80.

89. Talley NJ, Vakil N, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2324-37.

90. National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Dyspepsia: Managing dyspepsia in adults in primary care. London: NICE; 2004.

91. Mitchell RM, Collins JS, Watson RG, Tham TC. Differences in the diagnostic yield of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in dyspeptic patients receiving proton-pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists. Endoscopy. 2002;34:524-6.

92. Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Souchek J, Ambriz E. Impact of upper endoscopy on satisfaction in patients with previously uninvestigated dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:295-9.

93. Lassen A, Pedersen F, Bytzer P, et al. Helicobacter pylori test-and-eradicate versus prompt endoscopy for management of dyspeptic patients: A randomized trial. Lancet. 2000;356:455-60.

94. Quadri A, Vakil N. Health-related anxiety and the effect of open-access endoscopy in US patients with dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:835-40.

95. Hallissey MT, Allum WH, Jewkes AJ, et al. Early detection of gastric cancer. BMJ. 1990;301:513-15.

96. Sue-Ling HM, Johnston D, Martin IG, et al. Gastric cancer: A curable disease in Britain. BMJ. 1993;307:591-6.

97. Canga CIII, Vakil N. Upper GI malignancy, uncomplicated dyspepsia, and the age threshold for early endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:600-3.

98. Ford AC, Qume M, Moayyedi P, et al. Helicobacter pylori “test and treat” or endoscopy for managing dyspepsia: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1838-44.

99. Delaney B, Ford AC, Forman D, et al. Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (4):CD001961.

100. Ofman J, Rabeneck L. The effectiveness of endoscopy in the management of dyspepsia: A qualitative systematic review. Am J Med. 1999;106:335-46.

101. Makris N, Barkun A, Crott R, Fallone C. Cost-effectiveness of alternative approaches in the management of dyspepsia. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:446-64.

102. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: The Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-81.

103. Ford AC, Delaney BC, Forman D, Moayyedi P. Eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease in Helicobacter pylori–positive patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (2):CD003840.

104. Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: A combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347-53.

105. Delaney B, McColl K. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(Suppl 1):32-40.

106. Vakil N, Rhew D, Soll A, Ofman J. The cost-effectiveness of diagnostic testing strategies for Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1691-8.

107. Chiba N, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Sinclair P, et al. Treating Helicobacter pylori infection in primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia: The Canadian Adult Dyspepsia Empiric Treatment-Helicobacter pylori positive (CADET-Hp) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324:1012-16.

108. Delaney BC, Wilson S, Roalfe A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of initial endoscopy for dyspepsia in patients over age 50 years: A randomised controlled trial in primary care. Lancet. 2000;356:1965-9.

109. Farkkila M, Sarna S, Valtonen V, Sipponen P. Does the “test and treat” strategy work in primary health care for management of uninvestigated dyspepsia? A prospective two-year follow-up study of 1552 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;39:327-35.

110. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Jarbol DE, et al. Meta-analysis: Helicobacter pylori “test and treat”: compared with empirical acid suppression for managing dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:534-44.

111. McColl KE, Murray LS, Gillen D, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopy with testing for Helicobacter pylori compared with non-invasive H pylori testing alone in the management of dyspepsia. BMJ. 2002;324:999-1002.

112. Jones R, Tait C, Sladen G, Weston-Baker J. A trial of a test-and-treat strategy for Helicobacter pylori positive dyspeptic patients in general practice. Int J Clin Pract. 1999;53:413-16.

113. Heaney A, Collins JSA, Watson RGP, et al. A prospective randomised trial of a ‘’test and treat’’ policy versus endoscopy based management in young Helicobacter pylori–positive patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia, referred to a hospital clinic. Gut. 1999;45:186-90.

114. Ladabaum U, Chey WD, Scheiman JM, Fendrick AM. Reappraisal of non-invasive management strategies for uninvestigated dyspepsia: A cost-minimization analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1491-501.

115. Spiegel B, Vakil N, Ofman J. Dyspepsia management in primary care: A decision analysis of competing strategies. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1270-85.

116. Rabeneck L, Souchek J, Wristers K, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3045-51.

117. Talley NJ, Lauritsen K. The potential role of acid suppression in functional dyspepsia: The BOND, OPERA, PILOT, and ENCORE studies. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 4):iv36-41.

118. Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable bowel syndrome: Long-term prognosis and the physician- patient interaction. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:107-12.

119. Elta GH, Behler EM, Colturi TJ. Comparison of coffee intake and coffee-induced symptoms in patients with duodenal ulcer, nonulcer dyspepsia and normal controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1339-42.

120. Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. Smoking, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in outpatients with functional dyspepsia and among dyspepsia subgroups. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:524-8.

121. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4):CD001960.

122. Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, et al. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: A systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329-37.

123. McColl KE. Protagonist: Should we eradicate Helicobacter pylori in non-ulcer dyspepsia? Gut. 2001;48:759-61.

124. Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Jones M, Verlinden M, Talley N. Efficacy of cisapride and domperidone in functional (nonulcer) dyspepsia: A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:689-96.

125. Karamanolis G, Tack J. Promotility medications—now and in the future. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;24:297-307.

126. Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Snape W, et al. Failure of a motilin receptor agonist (ABT-229) to relieve the symptoms of functional dyspepsia in patients with and without delayed gastric emptying: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1653-61.