Chapter 18 Dysmenorrhoea and menstrual complaints

AETIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

Menstrual complaints are often broadly – and sometimes incorrectly – categorised under the broad moniter of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). PMS is defined as a recurrent set of physical and behavioural symptoms occurring cyclically 7–14 days before menstruation (the luteal phase) and are troublesome enough to interfere with some aspects of the female’s life.1 In common clinical usage this has also extended to symptoms (such as dysmenorrhoea) that occur during menstruation and cease by the end of the full flow of menses. Despite its high prevalence PMS remains poorly understood and often not prioritised in medical treatment.1 Multiple aetiologies have been proposed, most prominently those in Table 18.1. In reality a number of these may be responsible for underlying imbalances, even in the same patient. The numerous proposed aetiologies for PMS mean that more than 150 individual symptoms have been associated with the condition. The most common are listed in Table 18.2.1

| CATEGORY | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|

| Fluid and electrolyte balance |

Table 18.2 The most common symptoms of premenstrual syndrome

| Abdominal bloating | Depression | Lethargy |

| Anxiety | Dizziness | Low self-esteem |

| Back pain | Fatigue | Mood swings |

| Breast tenderness | Headache | Nervousness |

| Change in appetite | Insomnia | Social isolation |

| Clumsiness | Irritability | Sugar cravings |

| Constipation | Joint pain | Water retention |

Although diagnosis is difficult given the broad range of possible aetiologies and symptoms, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a more severe form of PMS, is a recent addition to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV.2 To be diagnosed with PMDD a woman must have at least five of the following symptoms occurring cyclically at a level serious enough to interfere with normal daily activities:

Patients fulfilling the diagnositic criteria for PMDD also fulfil medical diagnostic criteria for PMS, but not necessarily vice versa. However, it may be viewed as disturbing that behavioural aspects form the focus of diagnosis in PMDD, when in clinical practice a vast array of hormonal and physiological interactions take place within a woman’s body around the time of menstruation, resulting in a variety of broader symptoms and forming a more complex basis of underlying aetiology.

Dysmenorrhoea

Primary dysmenorrhoea classically presents as a cramping lower abdominal pain that usually begins during the day before menstruation. The pain gradually eases after the start of menstruation and is sometimes gone by the end of the first day of bleeding. Primary dysmenorrhoea occurs in a high percentage of young women only in ovulatory cycles and the pain is normally limited to the first 48 to 72 hours of menstruation.1

Hormonal and biochemical influences

Endocrine studies have suggested that PMS is not the result of a simple excess or deficiency in certain hormone levels.3 Low progesterone,4 excessive oestrogen5 or normal levels of both6 have not been associated with increasing incidence of PMS. Though prolactin levels have been associated with several symptoms of PMS there has been little hard evidence to suggest that elevated prolactin levels are present in women with PMS.6,7 Similarly while aldosterone is thought to be at least partly responsible for the congestive symptoms of PMS there have been no reports of significant differences between women with and without PMS.5 It has been postulated that PMS is not associated with abnormal hormone levels, but rather an abnormal response to sex hormones8 which may be exacerbated during episodes of stress.9 High blood flow is also associated with an increased instance of dysmenorrhoea.10

It is thought that deviations from normal ovarian function—rather than hormone levels per se—are associated with changes to other body systems (such as neurotransmitters) seen in PMS.11 Serotonin is thought to be particularly affected by changes in hormone levels and responsible for many mood change symptoms associated with PMS.12

It has also been hypothesised that women with PMS may have lower levels of circulating endogenous opiates (or serotonin) or a more sudden withdrawal after the postovulation surge, leaving them more susceptible to depression and more sensitive to pain in the luteal phase.13–15 Prostaglandins are also associated with the PMS symptoms of breast pain, fluid retention, abdominal cramping, headaches, irritability and depression.16 The high levels of the leukotrienes that increase uterine muscle spasm (C4 and D4) in the menstrual blood of women with dysmenorrhoea also support the hypothesis that prostaglandins are an important part of the aetiology.17 Anti-inflammatory prostaglandins may also be associated with reducing the exaggerated effects of prolactin.18

Psychosocial factors can also influence the menstrual cycle. Emotional and physical stressors such as travel, illness, stress, weather changes and other environmental factors can influence the length of the menstrual cycle, ovulation and severity of PMS.19 One study found that 75% of women receiving care for PMS had another diagnosis that could account for their symptom complex—predominantly depression and other mood disorders.20

RISK FACTORS

Epidemiological data observe a strong relationship between smoking or exposure to tobacco products and a higher incidence of dysmenorrhoea.21–23 Obesity is also a risk factor for menstrual disturbances, with women who have a body mass index (BMI) over 30 incurring a threefold risk of developing them.24 Approximately three-quarters of women have a separate diagnosis—particularly mood disorders or other hormone-mediated diagnoses—that contribute significantly to their symptoms.25 High levels of caffeine may be associated with increased prevalence and severity of PMS symptoms,26,27 though this may be due to an additive relationship of sugar with caffeine.28 Many women medicate themselves with caffeine during PMS symptoms, which may exacerbate their symptoms.29

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Various pharmaceutical agents are used in conventional treatment, including diuretics (such as spironolactone—particularly with fluid retention), vitamins (such as B6), SSRI agents or danazol (particularly with severe mastalgia).30 Hormone therapy is also common, and consists of hormonal agents such as oral contraceptive pill (OCP), progestogens or implants. However, these have little evidence of efficacy in PMS.31 Progesterone treatment is increasingly popular, particularly amongst integrative medical practitioners; however, the evidence for effective treatment with progesterone alone is unclear.32

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

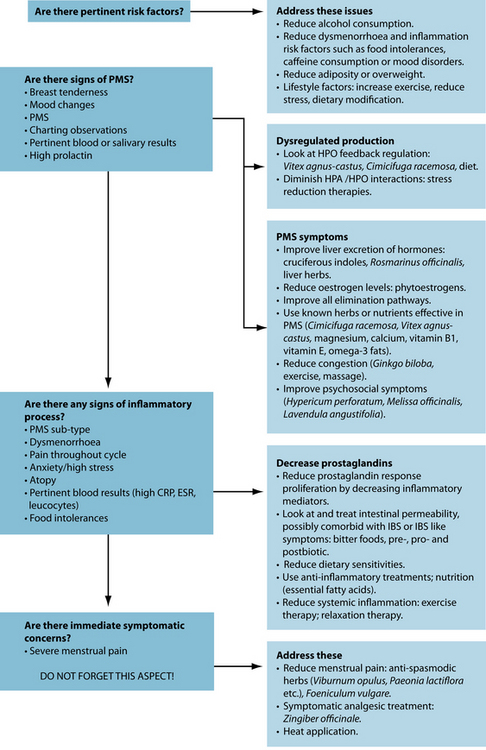

Although various diagnoses can often present in menstrual disorders, naturopathic treatment focuses not on treatment of particular disorders, but rather the restoration of a normal menstrual cycle. Other chapters in the reproductive section focus on various aspects of hormone normalisation, so this chapter focuses on specific symptoms associated with PMS, particularly dysmenorrhoea as it is often the most encountered symptom in clinical practice. A normal menstrual cycle should be free of the discomfort associated with pathological conditions such as PMS, PMDD or dysmenorrhoea. This eturn to normalcy can be sought through a number of mechanisms, most commonly hormonal regulation via the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis.

HPO-axis regulation

Dietary factors

Dietary factors may also play a significant role. Women with PMS typically consume more dairy products, refined sugar and high sodium foods than women without PMS.33 Fish, eggs and fruit have been associated with less dysmenorrhoea while wine is associated with more.36 Women following a low-fat, vegetarian diet also had lower incidence

of dysmenorrhoea.22,23,37 This was theorised to be due to increased sex-hormone binding globulin (which was measured in the study) and its effects on oestrogen or arachidonic acid. A diet high in oily fish and avoidance of foods with significant arachidonic acid content reduces the severity of dysmenorrhoea, possibly through improving the synthesis of anti-inflammatory prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Higher amounts of fibre have been associated with lower levels of menstrual pain.38 High intakes of total and saturated fats and low unrefined carbohydrate and fibre consumption were also associated with dysmenorrhoea.39

Regulating blood sugar levels may be important in modulating hormonal status. It has been observed that PMS symptoms are worse in women with abnormal glucose tolerance.40 The body appears more sensitive to insulin during the luteal phase; this has led some researchers to theorise that hypoglycaemia may account for some premenstrual symptoms. Consumption of foods high in sugar content—particularly chocolate—may also increase the severity of menstrual symptoms.28 Regulating eating patterns may therefore help to improve dysmenorrhoea—eating breakfast was associated with a lower incidence of dysmenorrhoea41 as was a history of calorie-restrictive dieting.42 This relationship was also observed irrespective of BMI.43

Other lifestyle factors

Increased or regular exercise is associated with lower incidence of dysmenorrhoea and most other premenstrual symptoms.44–49 This may be due in part to the apparent hormone normalisation role of exercise or increased physical activity,50 or its effects on stress reduction in women with dysmenorrhoea.51 More detailed information on the effects of stress on reproductive function can be found in Chapter 20 on polycystic ovarian syndrome and Chapter 31 on fertility, preconception care and pregnancy.

A study of 380 women found that those with higher levels of stress were twice as likely to experience dysmenorrhoea in their cycle.52 Relaxation therapy through various meditative or relaxation techniques has been demonstrated to improve premenstrual symptoms and dysmenorrhoea.53,54

PMS supplements

Herbal medicines

Vitex agnus-castus has had demonstrated effect in the treatment of a variety premenstrual symptoms.55–58 V. agnus-castus reduces prolactin through its action on dopamine receptors.57–62 However, other studies have suggested a dose-dependent effect, as lower doses (120 mg) were found to increase secretion while higher doses (204–480 mg) were found to decrease secretion.63 It may also have effects on progesterone levels; one study has shown it can normalise progesterone levels in women with hyperprolactinaemia within 3 months61 while another has suggested it can stimulate progesterone receptor expression.64 Recent research has suggested that V. agnus-castus may exert activity in the opiate system, and the activation of mood regulatory and analgesic pathways via this system may be at least partly responsible for its efficacy in menstrual disorders.65

Cimicifuga racemosa is thought to modulate oestrogen levels by reducing LH secretion.66,67 Although no clinical studies are available it has a strong tradition of use in dysmenorrhoea and menstrual disorders and has been approved by Commission E for use in these conditions.34,35,68

Tea from the leaves of Rosa gallica has also been demonstrated to mildly improve dysmenorrhoea and other menstrual symptoms in women.69 Psidii guajavae folium (guava) has been demonstrated to be effective in dysmenorrhoea.70 Matricaria recutita has been commonly used for treatment of dysmenorrhoea.71 Uterine tonic herbs may also be used in PMS treatment (see Chapter 31).

Hypericum perforatum may be useful in women displaying irritability or depression in PMS, and one small pilot trial has demonstrated a significant reduction in PMS symptom scores.72 Other nervine herbs such as Valeriana officinalis, Piper methysticum, Passiflora incarnata and Melissa officinalis have also been traditionally used in PMS for similar circumstances.34,35,68 Ginkgo biloba has also demonstrated improvement in psychosocial aspects of PMS, though it is most effective at reducing congestive symptoms such as breast pain, tenderness and fluid retention.73

Nutritional medicines

Calcium supplementation has been shown to reduce PMS symptoms.74,75 Women who had 1000–1200 mg calcium reported that their menstrual pain reduced by half.74 Magnesium has also been shown to reduce PMS mood and fluid retention symptoms.76,77 Although serum magnesium levels are often normal in women with PMS, they can have lower red blood cell magnesium levels than women without and levels are known to fluctuate throughout the cycle.78–80 Vitamin E can be useful for breast symptoms, tension, irritability and lack of co-ordination in PMS.81–83 Vitamin A also has a long history of use in PMS treatment.84 Zinc levels have also been demonstrated to be low in women with PMS.85

Symptomatic pain relief

Topical application of warmth

There may be an element of clinical truth in the traditional habit of curling up with a hot water bottle. Application of heat to the abdomen has also been demonstrated to be at least as effective as ibuprofen or paracetamol in clinical studies.86,87 Massage with liniments or warming salves (for example ginger) or moxibustion may also offer relief.

Herbal smooth muscle relaxants

Herbs with demonstrated ability to relax smooth muscle, such as Valeriana officinalis (though in animal studies only),88 Lavendula angustifolia,89 Matricaria recutita90 and Foeniculum vulgare91 may be used in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea, usually beginning a few days before menstruation and continuing until bleeding stops. Zingiber officinale has been shown to be equally effective as the NSAIDs ibuprofen and mefenamic acid in the symptomatic treatment of menstrual pain.92 This may be particularly useful in women who experience nausea in conjunction with menstrual pain. It can be taken as an infusion or several preparations—often sold for travel sickness or nausea—are available. F. vulgare was found to reduce the severity of dysmenorrhoea when taken (20 drops of liquid tincture five times per day) during the first 3 days of menses and is thought to be as effective as commonly used conventional analgesics.93

Viburnum opulus and V. prunifolium both have a strong tradition of use as uterine relaxants34,35,68 in addition to many early case reports,94,95 though they are yet to be clinically studied. While these are not symptomatic in the sense that they immediately resolve symptoms, they are effective only in treating the symptoms of dysmenorrhoea and do not address the underlying cause.

Endocrine interactions

In addition to high blood sugar or cortisol, low thyroid function may exacerbate PMS symptoms and low thyroid function has been found in women with PMS.96–98 The menstrual cycle appears to have an effect on thyroid function, with rT3 concentrations found to be higher in the luteal as opposed to follicular phase.97 Given the complex interactions that exist between hormonal systems this is not unusual. Thyroid treatment is expanded in Chapter 17 on thyroid abnormalities.

OTHER THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

TRADITIONAL HERBAL REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE34,35,68

Fluid retention

Diuretics such as Taraxacum officinale have traditionally been used for symptoms of fluid retention.

Uterine tonics

Uterine tonics are herbs that have traditionally been used for their normalising effect on the uterus and assisting with normal uterine function. They include Rubus idaeus, Angelica sinensis, Chamaelirium luteum, Aletris farinose, Caulophyllum thalictroides and more recently Tribulus terrestris.

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Oral contraceptive use

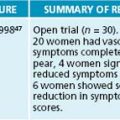

Vitamin B6 supplementation can restore biochemical values and treat PMS symptoms in women taking oral contraception.99 Hormone supplementation is also commonly used in conventional medicine to treat menstrual symptoms and may affect levels of vitamins A, B2, B3, B5, B12 and folate. OCP use may also reduce the action of Vitex agnus-castus.100

Acupressure

Acupressure has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for dysmenorrhoea.101,102

Traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese herbal medicine was found to be more effective than acupuncture in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea103 and a variety of effective herbal treatments are available.104 As prescription is usually determined by a physical state diagnosis based on a classical Chinese understanding of the human body, a comprehensive knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine theory is required to appropriately prescribe many of these herbal formulations.105 Acupuncture has also been found to be moderately effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhoea. This was best seen in patients who committed to weekly treatments and was most effective when combined with herbal and dietary treatments.

Chiropractic

A Cochrane review of spinal manipulation in dysmenorrhoea found spinal manipulation to be no better than sham manipulation, though did suggest it was more effective than no treatment.106

Qi gong

Chinese exercise therapy or Qi gong has also had documented encouraging success in alleviating various premenstrual symptoms.107,108

Homoeopathy

A small preliminary pilot study has demonstrated a positive effect of individualised homoeopathic treatment on premenstrual symptoms, with at least 30% improvement in symptoms observed in 90% of patients receiving homoeopathy versus 37.5% of those who were not.109

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) has been demonstrated as a non-invasive, clinically significant intervention for dysmenorrhoea.110 TENS may also reduce cortisol and prolactin levels through the opioid-modulating analgesia system.111

Aromatherapy

Topical application of a 2:1:1 mixture of the aromatherapy oils Lavandula officinalis, Salvia sclarea and Rosa centifolia was demonstrated to be effective in symptomatic treatment of dysmenorrhoea in one small study.112 Other aromatherapy treatments may also be suitable.

Massage

Regular massage may be a useful adjunct therapy in severe perimenstrual disorders. One small trial has demonstrated positive effects on pain and water retention in the longer term but only short-term benefit for mood and anxiety.113 Another small trial of abdominal massage using TCM meridian theory has also shown benefit in regard to perimenstrual symptoms such as pain and bloating.114

Example treatment

The patient was given a herbal tablet of Vitex agnus-castus to help modulate HPO activity. A combination herbal tablet as in the ‘Herbal formula’ box was also given to provide symptomatic relief. Its rationale is anti-spasmodic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic. The patient was also prescribed 6000 mg of fish oil daily to provide anti-inflammatory action and address nutritional deficiencies.

Taken 3–4 times daily 2 days before period until 2 days after

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

Pain reduction in dysmenorrhoea is the most commonly sought treatment in PMS. Many of the other symptoms of PMS are related to the same underlying issue. A symptomatic treatment for menstrual cramping (such as the Viburnum mix) should be given in line with this request; however, eventual HPO modulation or menstrual cycle correction should remain the ultimate goal. Smooth muscle relaxants or uterine tonics alone should never constitute the entirety of treatment. Noticeable improvement should occur within the first cycle and continue throughout the cycles. After a few cycles of noticeably less pain the symptomatic treatments should be ceased and the prescription should focus on HPO modulation and its effectors only.

KEY POINTS

Altman G., et al. Increased symptoms in female IBS patients with dysmenorrhea and PMS. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29(1):4-11.

Girman A., et al. An integrative medicine approach to premenstrual syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5 Suppl):S56-S65.

Hudson T. Women’s encyclopedia of natural medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Ozgoli G., et al. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:129-132.

Proctor M., et al. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhoea. BMJ. 2006;332(7550):1134-1138.

Trickey R. Women, hormones and the menstrual cycle: herbal and medical solutions from adolescence to menopause. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

1. Edmonds K., editor. Obstetrics and gynaecology. London: Blackwell, 2007.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Roca C., et al. Implications of endocrine studies of premenstrual syndrome. Psychiat Ann. 1996;26:576-580.

4. Backstrom T., Carstensen H. Estrogen and progesterone in plasma in relation to premenstrual tension. J Steroid Biochem. 1974;5:257-260.

5. Munday M., et al. Correlations between progesterone, estradiol and aldosterone levels in the premenstrual syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1981;14(1):1-9.

6. Rubinow D., et al. Changes in plasma hormones across the menstrual cycle in patients with menstrually related mood disorder and in control subjects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:5-11.

7. O’Brien P., Symonds E. Prolactin levels and the premenstrual syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;89:306-308.

8. Dalton K. The aetiology of premenstrual syndrome is with the progesterone receptors. Med Hypotheses. 1990;31:323-327.

9. Nock B. Noradrenergic regulation of progestin receptors: new findings. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;474:415-422.

10. Sundell G., et al. Factors influencing the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea in young women. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;97:588-594.

11. Rubinow D., Schmidt C. The treatment of premenstrual syndrome—forward into the past. New Engl J Med. 1995;332:1574-1575.

12. Kessel B. Premenstrual syndrome: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27(3):625-639.

13. Chuong C., et al. Neuropeptide levels in the premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1985;44:760-765.

14. Rapkin A. The role of serotonin in the premenstrual syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1992;35(3):629-636.

15. Steiner M., Pearlstein T. Premenstrual dysphoria and the serotonin system: pathophysiology and treatment J. Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(12):S17-S21.

16. Budoff P. The use of prostaglandin inhibitors for the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:465-468.

17. Nigam S., et al. Increased concentrations of eiconasoids and platelet-activating factor in menstrual blood from women with primary dysmenorrhoea. Eicosanoids. 1991;4(3):137-141.

18. Horrobin D. The role of essential fatty acids and prostaglandins in the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1983;28(7):465-468.

19. Hamilton J., et al. Premenstrual mood changes: a guide to evaluation and treatment. Psychiat Ann. 1984;30:474-482.

20. DeJong R., et al. Premenstrual mood disorder and psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiat. 1985;142:1359-1361.

21. Chen C., et al. Prospective study of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and dysmenorrhea. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(11):1019-1022.

22. Hornsby P., et al. Cigarette smoking and disturbance of menstrual function. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):193-198.

23. Parazzini F., et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and risk of primary dysmenorrhea. Epidemiology. 1994;5(4):469-472.

24. Masho S., et al. Obesity as a risk factor for premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(1):33-39.

25. DeJong R., et al. Premenstrual mood disorder and psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1359-1361.

26. Rossignol A., Bonnlander H. Caffeine-containing beverages, total fluid consumption, and premenstrual syndrome. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(9):1106-1110.

27. Rossignol A., et al. Tea and premenstrual syndrome in the People’s Republic of China. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(1):67-69.

28. Rossignol A., Bonnlander H. Prevalence and severity of the premenstrual syndrome. Effects of foods and beverages that are sweet or high in sugar content. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:131-136.

29. Rossignol A., et al. Do women with premenstrual symptoms self-medicate with caffeine? Epidemiology. 1991;2(6):403-408.

30. Murtagh J. General practice. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

31. Wyatt K. Premenstrual syndrome. Clin Evid. 2000;9:2125-2144.

32. Ford O., et al. Progesterone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2006. CD003415

33. Abraham G. Nutritional factors in the etiology of the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:446-464.

34. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

35. Blumenthal M., et al, editors. Herbal medicine: expanded Commission E monographs (English translation). Austin: Integrative Medicine Communications, 2000.

36. Balbi C., et al. Influence of menstrual factors and dietary habits on menstrual pain in adolescence age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91(2):143-148.

37. Barnard N., et al. Diet and sex-hormone binding globulin, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(2):245-250.

38. Nagata C., et al. Associations of menstrual pain with intakes of soy, fat and dietary fiber in Japanese women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(1):88-92.

39. Nagata C., et al. Soy, fat and other dietary factors in relation to premenstrual symptoms in Japanese women. BJOG. 2004;111(6):594-599.

40. Roy S., et al. Changes in glucose oral tolerance during normal menstrual cycle. J Indian Med Assoc. 1971;57(6):201-204.

41. Fujiwara T. Skipping breakfast is associated with dysmenorrhoea in young women in Japan. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2003;54(6):505-509.

42. Fujiwara T. Diet during adolescence is a trigger for subsequent development of dysmenorrhea in young women. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;58(6):437-444.

43. Montero P., et al. Influence of body mass index and slimming habits on menstrual pain and cycle irregularity. J Biosoc Sci. 1996;28(3):315-323.

44. Golomb L., et al. Primary dysmenorrhea and physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):906-909.

45. Pullon S., et al. Treatment of premenstrual symptoms in Wellington women. N Z Med J. 1989;102(862):72-74.

46. Jahromi M., et al. Influence of a physical fitness course on menstrual cycle characteristics. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(11):659-662.

47. Aganoff J., Boyle G. Aerobic exercise, mood states and menstrual cycle symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:183-192.

48. Choi P., Salmon P. Symptom changes across the menstrual cycle in competitive sportswomen, exercisers and sedentary women. Br J Clin Pschol. 1995;34(3):447-460.

49. Prior J., Vigna Y. Conditioning exercise and premenstrual symptoms. Reprod Med. 1987;32:423-428.

50. Stoddard J., et al. Exercise training effects on premenstrual distress and ovarian steroid hormones. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99(1):27-37.

51. Lustyk M., et al. Stress, quality of life and physical activity in women with varying degrees of premenstrual symptomatology. Women Health. 2004;39(3):35-44.

52. Wang L., et al. Stress and dysmenorrhoea: a population based prospective study. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(12):1021-1026.

53. Goodale I., et al. Alleviation of premenstrual syndrome with the relaxation response. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(4):649-655.

54. Arias A., et al. Systematic review of the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for medical illness. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;12(8):817-823.

55. Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective, randomised, placebo controlled study. BMJ. 2001;322(7279):134-137.

56. Loch E., et al. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome with a phytopharmaceutical formulation containing Vitex agnus castus. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(3):315-320.

57. Wuttke W., et al. Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus)—pharmacology and clinical indications. Phytomed. 2003;10(4):348-357.

58. Berger D., et al. Efficacy of Vitex agnus-castus L. Extract Ze 440 in patients with pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2000;264(3):150-153.

59. Jarry H., et al. In vitro prolactin but not LH and FSH release is inhibited by compounds in extracts of Agnus castus: direct evidence for a dopaminergic principle by the dopamine receptor assay. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1994;102(6):448-454.

60. Sliutz G., et al. Agnus castus extracts inhibit prolactin secretion of rat pituitary cells. Horm Metab Res. 1993;25(5):253-255.

61. Milewicz A., et al. [Vitex agnus-castus extract in the treatment of luteal phase defects due to latent hyperprolactinemia. Results of a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study] [in German]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;43(7):752-756.

62. Meier B., et al. Pharmacological activities of Vitex agnus-castus extracts in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(5):373-381.

63. Merz P., et al. The effects of a special Agnus castus extract (BP1095E1) on prolactin secretion in healthy male subjects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1996;104(6):447-453.

64. Liu J. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of plant extracts for the potential treatment of menopausal symptoms. J Agricult Food Chem. 2001;49(5):2472-2479.

65. Webster D., et al. Activation of the mu-opiate receptor by Vitex agnus-castus methanol extracts: implication for its use in PMS. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;106(2):216-221.

66. Duker E., et al. Effects of extracts from cimicifuga racemosa on gonadotrophin release in menopausal women and ovariectomized rats. Planta Med. 1991;57(5):420-424.

67. Seidlova-Wuttke, et al. Evidence for selective estrogen receptor modulator activity in a black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) extract: comparison with estradiol-17 beta. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149:351-362.

68. Scientific Committee of the British Herbal Medical Association. British herbal pharmacopoeia, 1st edn. Bournemouth: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1983.

69. Tseng Y., et al. Rose tea for relief of primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial in Taiwan. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(5):e51-57.

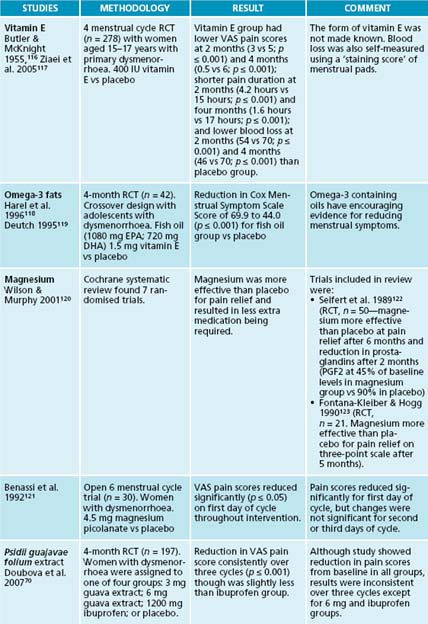

70. Doubova S., et al. Effect of a Psidii guajavae folium extract in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(2):305-310.

71. Banikarim C., et al. Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea on Hispanic female adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1226-1229.

72. Stevinson C., Ernst E. A pilot study of Hypericum perforatum for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. BJOG. 2000;107(7):870-876.

73. Tamborini A., Taurelle R. [Value of standardized Ginkgo bilobaextract (EGb 761) in the management of congestive symptoms of premenstrual syndrome]. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1993;88(7–9):447-457.

74. Thys-Jacobs S., et al. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(2):444-452.

75. Thys-Jacobs S., et al. Calcium supplementation in premenstrual syndrome. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:183-189.

76. Facchinetti F., et al. Oral magnesium successfully relieves premenstrual mood changes. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:177-181.

77. Walker A., et al. Magnesium supplementation alleviates premenstrual symptoms of fluid retention. J Womens Health. 1998;7:1157-1165.

78. Abraham G., Lubran M. Serum red cell magnesium levels in patients with PMT. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:2364-2366.

79. Sherwood R., et al. Magnesium and the premenstrual syndrome. Ann Clin Biochem. 1986;23:667-670.

80. Facchinetti F., et al. Premenstrual increase of intracellular magnesium levels in women with ovulatory, asymptomatic menstrual cycles. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1988;2:249-256.

81. London R., et al. Evaluation and treatment of breast symptoms in women with the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1981;28:503-508.

82. London R., et al. The effect of alpha-tocopherol on premenstrual symptomatology: a double-blind study. J Am Coll Nutr. 1983;2(2):115-122.

83. London R., et al. Efficacy of alpha-tocopherol in the treatment of the premenstrual syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(6):400-404.

84. Argonz J., Abinzano C. Premenstrual tension treated with vitamin A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1950;10(12):1579-1590.

85. Chuong C., Dawson E. Zinc and copper levels in premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:313-320.

86. Akin M., et al. Continuous, low-level, topical heat wrap therapy as compared to acetaminophen for primary dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(9):739-745.

87. Akin M., et al. Continuous low-level topical heat in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(3):343-349.

88. Hazelhoff B., et al. Antispasmodic effects of Valeriana compounds: an in-vivo and in-vitro study on the guinea pig ileum. Arch Int Pharmacdyn Ther. 1982;257:274-287.

89. Lis-Belchin M., Hart S. Studies on the mode of action of the essential oil of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia). Phytother Res. 1999;13(6):540-542.

90. Achterrath-Tuckermann U., et al. Pharmacological investigations with compounds of chamomile. V. Investigations on the spasmolytic effect of compounds of chamomile and Kamillosan on the isolated guinea pig ileum. Planta Med. 1980;39(1):38-50.

91. Ostad S., et al. The effect of fennel essential oil on uterine contraction as a model for dysmenorrhea, pharmacology and toxicology study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76(3):299-304.

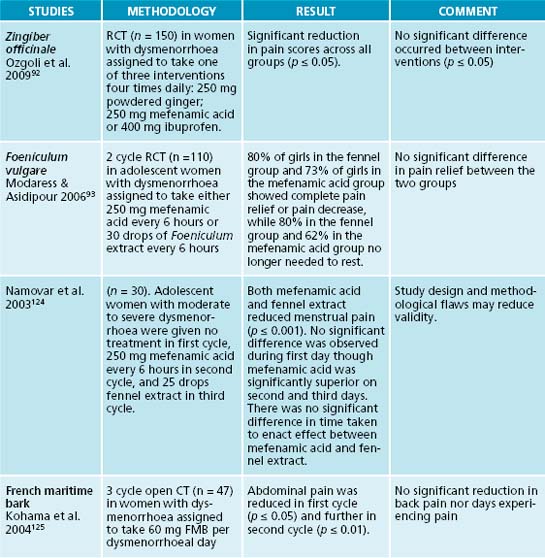

92. Ozgoli G., et al. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009. [Epub ahead of print]

93. Modaress Nejad V., Asadipour M. Comparison of the effectiveness of fennel and mefenamic acid on pain intensity in dysmenorrhoea. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12(3–4):423-427.

94. Munch J., Pratt H. The uterine-sedative action of authentic Viburnum. XI. Bioassay methods. Pharmaceut Arch. 1941;12:88-91.

95. Jarboe C., et al. Uterine relaxant properties of Viburnum. Nature. 1966;212:837.

96. Brayshaw N., Brayshaw D. Thyroid hypofunction in premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1486-1487.

97. Girdler S., et al. Thyroid axis function during the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20(4):395-403.

98. Schmidt P., et al. Thyroid function in women with premenstrual syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(3):671-674.

99. Bermond P. Therapy of side effects of oral contraceptive agents with vitamin B6. Acta Vitaminol Enzymol. 1982;4(1–2):45-54.

100. Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence based guide. Melbourne: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

101. Taylor D., et al. A randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of an acupressure device (relief brief) for managing symptoms of dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:357-370.

102. Pouresmail Z., Ibrahimzadeh R. Effects of acupressure and ibuprofen on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. J Trad Chin Med. 2002;22:205-210.

103. Zhu X., et al. Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008. CD005288

104. Jia W., et al. Common traditional Chinese medicinal herbs for dysmenorrhea. Phytother Res. 2006;20(10):819-824.

105. Maciocia G. Obstetrics and gynecology in Chinese medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

106. Proctor M., et al. Spinal manipulation for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2006. CD002119

107. Jang H., Lee M. Effects of qi therapy (external qigong) on premenstrual syndrome: a randomized placebo controlled study. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:456-462.

108. Jang H., et al. Effects of qi-therapy on premenstrual syndrome. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114:909-921.

109. Yakir M., et al. Effects of homeopathic treatment in women with premenstrual syndrome: a pilot study. Br Homeopath J. 2001;90:148-153.

110. Proctor M., et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2002. CD002123

111. Akinbo S., et al. Effect of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) on hormones profile in subjects with primary dysmenorrhoea—a preliminary study. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2007;63(3):45-48.

112. Han S., et al. Effect of aromatherapy on symptoms of dysmenorrhea in college students: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(6):535-541.

113. Hernandez-Reif M., et al. Premenstrual symptoms are relieved by massage therapy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21(1):9-15.

114. Kim J., et al. [The effects of abdominal meridian massage on menstrual cramps and dysmenorrhea in full-time employed women]. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35(7):1325-1332.

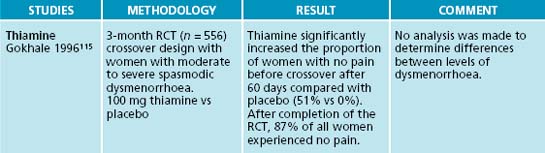

115. Gokhale L. Curative treatment of primary (spasmodic) dysmenorrhoea. Indian J Med Res. 1996;103:227-231.

116. Butler E., McKnight E. Vitamin E in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. Lancet. 1955;268(6869):844-847.

117. Ziaei S., et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. BJOG. 2005;112(4):466-469.

118. Harel Z., et al. Supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1335-1338.

119. Deutch B. Menstrual pain in Danish women correlated with low n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49(7):508-516.

120. Wilson M., Murphy P. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2001. CD002124

121. Benassi L., et al. Effectiveness of magnesium pidolate in the prophylactic treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. Clin Experimental Obstet Gynecol. 1992;19(3):176-179.

122. Seifert B., et al. [Magnesium—a new therapeutic alternative in primary dysmenorrhea]. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1989;111(11):755-760.

123. Fontana-Klaiber H., Hogg B. [Therapeutic effects of magnesium in dysmenorrhea]. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1990;79(16):491-494.

124. Namavar Jahromi B., et al. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;80(2):153-157.

125. Kohama T., et al. Analgesic efficacy of French maritime pine bark extract in dysmenorrhea: an open clinical trial. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):828-832.