Drug eruptions

Reactions to drugs are common and often produce an eruption. Almost any drug can result in any reaction, although some patterns are more common with certain drugs. Not all reactions are ‘allergic’ in nature.

Aetiopathogenesis

Drug-induced skin reactions have several possible mechanisms:

Clinical presentation

Drug eruptions present in many guises and come into the differential diagnosis of several rashes. It is vital to obtain a detailed drug ingestion history. This must include ‘over-the-counter’ preparations (e.g. for headaches or constipation) not normally regarded as ‘drugs’ by the patient. A drug introduced during a 2-week period before the eruption starts must be viewed as the most likely culprit, although a reaction may occur to a drug taken safely for years. The majority of drug eruptions fit into a defined category (Table 1). The most severe and characteristic ones are outlined below. Other patterns are discussed in the relevant chapters. Drugs including non-steroidals or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, but especially lithium and chloroquine, can exacerbate existing psoriasis. Other agents, e.g. beta-blockers and gold, may provoke a psoriasis-like eruption.

| Drug eruption | Description | Drugs commonly responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Acneiform | Like acne: papulopustules, no comedones | Androgens, bromides, dantrolene, isoniazid, lithium, phenobarbital, quinidine, steroids |

| Bullous | Various types; some phototoxic, some ‘fixed’ | Barbiturates (overdose), furosemide, nalidixic acid (phototoxic), penicillamine (pemphigus-like) |

| Drug-induced exanthem | Commonest pattern (see text) | Antibiotics (e.g. amoxicillin), proton pump inhibitors, gold, thiazides, allopurinol, carbamazepine |

| Eczematous | Not common; seen when topical sensitization is followed by systemic treatment | Neomycin, penicillin, sulphonamide, ethylenediamine (cross-reacts with aminophylline), benzocaine (cross-reacts with chlorpropamide), parabens, allopurinol |

| Erythema multiforme | Target lesions (p. 82) | Antibiotics, anticonvulsants, ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, non-steroidals |

| Erythroderma | Exfoliative dermatitis (p. 44) | Allopurinol, captopril, carbamazepine, diltiazem, gold, isoniazid, omeprazole, phenytoin |

| Fixed drug eruption | Round red–purple plaques recur at same site | Antibiotics, tranquillizers, non-steroidals, phenolphthalein, paracetamol, quinine |

| Hair loss | Telogen effluvium (p. 66) Anagen effluvium (p. 66) |

Anticoagulants, bezafibrate, carbimazole, oral contraceptive pill, propranolol, albendazole, cytotoxic drugs, acitretin |

| Hypertrichosis | Excess vellus hair growth (p. 66) | Minoxidil, ciclosporin, phenytoin, penicillamine, corticosteroids, androgens |

| Lupus erythematosus (LE) | LE-like syndrome (p. 80) | Hydralazine, isoniazid, penicillamine, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, etanercept |

| Lichenoid | Like lichen planus (p. 40) | Chloroquine, beta-blockers, anti-TB drugs, penicillamine, diuretics, gold, captopril |

| Photosensitive | Sun-exposed sites, may blister or pigment (see Fig. 4) | Non-steroidals, ACE inhibitors, amiodarone, thiazides, tetracyclines, phenothiazines |

| Pigmentation | Melanin or drug deposition (see Fig. 5) | Amiodarone, bleomycin, psoralens, chlorpromazine, minocycline, antimalarials |

| Psoriasiform | Psoriasis-like appearance (see text) | Beta-blockers, gold, methyldopa; lithium and antimalarials exacerbate psoriasis |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Blistering skin with mucosal involvement (see text) | Antibiotics, anticonvulsants, non-steroidals, omeprazole, allopurinol, barbiturates |

| Urticaria | Many mechanisms (p. 76) | ACE inhibitors, penicillins, opiates, non-steroidals, X-ray contrast media, vaccines |

| Vasculitis | Immune complex reaction | Allopurinol, captopril, penicillins, phenytoin, sulphonamides, thiazides |

Drug-induced exanthem

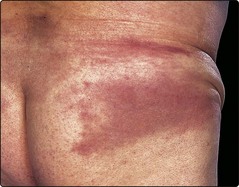

Drug-induced exanthem, the commonest type of drug eruption, may be morbilliform (measles-like) or urticarial, or may resemble erythema multiforme. It usually affects the trunk more than the extremities (Fig. 1), and may be accompanied by mild fever or followed by peeling of the skin. Haematological or biochemical disturbance does not arise. The eruption clears 1–2 weeks after stopping the offending drug.

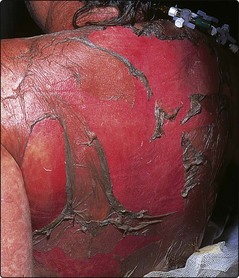

Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) represent a spectrum of disease, characterized by severe mucosal ulceration and blistering of the skin with different body surface area detachment (SJS 1–10%; SJS/TEN overlap 10–30%; TEN>30%). Both show significant systemic disturbance. Mucosal lesions may lead to scarring with a significant morbidity if the patient survives. The extensive skin loss results in problems of fluid and electrolyte balance, as seen with extensive burns, and TEN must be managed in a burns or intensive care unit (Fig. 2). Overall mortality is 30%.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)

DRESS commonly has a delayed onset of 3–4 weeks. The rash initially starts similarly to a drug-induced exanthem, but quickly it becomes apparent that the individual is systemically unwell. There is significant amount of tissue oedema, often on the head and neck, and widespread lymphadenopathy. Small pin-point pustules and superficial blisters may be evident. Systemic upset is characterized by fever and eosinophilia. Liver dysfunction is common but any organ system can become involved and may fail. On cessation of the offending drug, the rash may improve only to worsen again days later leading to confusion regarding the diagnosis. Reactivation of childhood viruses such as HHV6 and HHV7 have been demonstrated. Three to five days of oral prednisolone is usually effective.

Fixed drug eruption

This specific but uncommon eruption is characterized by round red or purplish plaques (Fig. 3) that recur at the same site each time the causative agent is taken. The lesions may blister and leave pigmentation on clearing.

Fig. 3 Toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The damaged epidermis has sheared off to leave extensive areas of eroded skin.

Fixed drug eruption, phototoxic reaction, drug-induced pemphigus and barbiturate overdosage (at pressure sites) may all blister (see Table 1).

Differential diagnosis

The exact differential diagnosis depends on the type of drug eruption. The determination of which drug is responsible depends on a detailed prescribing timeline and a knowledge of the potential of each drug to cause a reaction (Table 2). In severe or extensive cases, photography and histology should be obtained. Allergen-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E tests are not helpful, but patch tests may be of use in diagnosing a drug eruption. Assays of drug-induced T cell activation show promise but remain largely research based.

| Drug | Eruption |

|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | Pruritus, urticaria, toxic erythema |

| Antibiotics | Toxic erythema, urticaria, fixed drug eruption, erythema multiforme |

| Beta-blockers | Psoriasiform, Raynaud’s phenomenon, lichenoid eruption |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories | Toxic erythema, erythroderma, toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| Oral contraceptives | Melasma, alopecia, acne, candidiasis |

| Phenothiazines | Photosensitivity, pigmentation |

| Thiazides | Toxic erythema, photosensitivity, lichenoid eruption, vasculitis |

Management

Fig. 4 Photosensitivity.

This was caused by taking a thiazide diuretic, associated with being out of doors on a sunny day.

Drug eruptions

Drug reactions may be pharmacological or idiosyncratic, as well as immune mediated.

Drug reactions may be pharmacological or idiosyncratic, as well as immune mediated.

Drugs that commonly cause drug eruptions are amoxicillin, ACE inhibitors, anticonvulsants, thiazides and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Drugs that commonly cause drug eruptions are amoxicillin, ACE inhibitors, anticonvulsants, thiazides and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The commonest pattern is a drug-induced exanthem, often morbilliform.

The commonest pattern is a drug-induced exanthem, often morbilliform.

The most severe involvement is toxic epidermal necrolysis, which may be fatal.

The most severe involvement is toxic epidermal necrolysis, which may be fatal.

A drug eruption typically begins within 3 days of starting a drug (if it has been taken before) and clears about 2 weeks after stopping it.

A drug eruption typically begins within 3 days of starting a drug (if it has been taken before) and clears about 2 weeks after stopping it.

Withdrawal of the drug and avoidance of related compounds are necessary.

Withdrawal of the drug and avoidance of related compounds are necessary.

Provocation tests are not recommended because of the possibility of a severe reaction.

Provocation tests are not recommended because of the possibility of a severe reaction.